James Yee’s spiritual journey over the next decade, which eventually brought him to Cuba as the fourth Muslim chaplain assigned in less than a year to Camp Delta’s detainees, seems to have begun almost casually. At first, his conversion “did not feel particularly momentous,” he tells us in his memoir For God and Country. In his description, it sounds more like a consumer than a theological choice: accepting the “simplicity” of Islam’s belief in one God didn’t require trading in Jesus for Muhammad, as he saw it, but putting them more or less on a par as prophets. Although he had been raised as a Lutheran to believe in the Trinity, he had never considered religion to be a major factor in his life and didn’t see why it had to become one as a consequence of his conversion. Islam, at this stage, was a more comfortable creed, not a way of life.

To his apparent surprise, its claim on his attention gradually deepened, particularly when he was assigned to Saudi Arabia, after the first Gulf War, as an air defense artillery officer in a Patriot missile crew. Setting an example of religious tolerance that, needless to say, went unreciprocated, the American command allowed its troops to frequent a Saudi “cultural center” at King Abdul Aziz air base where non-Muslims were quietly proselytized—Yee claims that large numbers of Americans converted during the Gulf War—and Muslim servicemen could sign up for bus excursions to Mecca. Yee, who professes to have felt entirely at home in the relatively homogeneous New Jersey suburb where he’d grown up as a member of an ethnic minority, found a kind of liberation in the “diversity” of Islam. This was real multiculturalism, all those Asians, Africans, Iranians, and Turks mixed in with Arabs and praying on a footing of equality; this was indeed “momentous.” Mecca, as he experienced it on this first of three trips (the first a mere visit, the second two a proper Hajj), was what his father had always taught him America was supposed to be. “The diversity of Islam,” he writes, “was incredible…. I’d never seen anything as truly diverse as this.”

So moved was he that within two years he’d resigned from the army with the aim of pursuing Islamic studies to qualify as an imam and immersing himself in Arabic; within three years, this Chinese-American West Point graduate from New Jersey was enrolled in Abu Noor University in Damascus where he stayed four years, returning home with a Palestinian wife who kept herself covered and spoke only limited English. Captain Yee’s story is remarkable even before he was recruited back into the army as a Muslim chaplain, even before he was sent to Guantánamo. His story up to this point, before it turns really dark, has strong interest as a narrative of one American’s quest in the mall of religions, faiths, and cults that this country becomes for so many of its denizens. One would like to see what a novelist with a taste for American tales of improbable self-invention and cultural mutation, T.C. Boyle, perhaps, would do with it. To tell the rest of Captain Yee’s story would require Joseph Conrad.

Its subsequent episodes display the US military’s profound confusion about Islam: its self-congratulation and religiosity, which lead it to boast that it provides Korans, chaplain services, and an opportunity to pray in the direction of Mecca to those it detains indefinitely as “terrorists”; while its overriding devotion to its mission leads it to interfere with the religious practice of those same detainees in order to pressure them psychologically, squeeze them for intelligence they may or may not have held back, and, generally, show them who’s in charge. It’s asking a lot of the individual military policeman, not to mention the individual major general, to draw a fine line between the war on terror and a war on Islam, when Islam and their own misery are all that unite the inmates in the wire-mesh cages of a high-security prison. In this case, the major general was General Geoffrey Miller, who had been dispatched by Donald Rumsfeld to Camp Delta—and later Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq—with the specific charge of improving the “harvest” of what’s known as “actionable intelligence.”

Into this storm of cultural confusion and ruthless resolve walked the naive James Yee in November 2002, rendered even more so by his head-turning success in his first posting as a chaplain at Fort Lewis, Washington, where he’d won the warm approbation of his commanders who thus reinforced the conviction he’d formed in Mecca that there could be no conflict between service to Allah and service to America. In Yee’s eclectic theology, American values like religious freedom “are inherent in Islam and were a large part of what had led me to embrace this religion.” In the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the newly minted chaplain had initiated at Fort Lewis a series of “sensitivity training” sessions on Islam for officers and enlisted men, in which he earnestly argued that terrorist attacks on innocents were inimical to the teachings of the Koran. “This work was fulfilling,” he declares in For God and Country, written “with” (or perhaps by) a journalist, Aimee Molloy. “It was why I had become a chaplain.” Soon he was being sent to other military installations to make the same presentation and army publicists were arranging for him to be interviewed on National Public Radio and MSNBC. “I had become the US military’s poster child of a good Muslim,” he says.

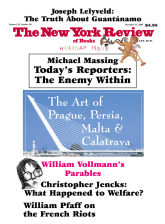

This Issue

December 15, 2005

-

*

In small doses, medical studies have shown, pepper spray causes a burning sensation and extreme pain. Pepper spray in large doses has been reported to result in coughing, gagging, even respiratory or cardiac arrest. None of these are effects Yee mentions in his description of cell “extractions” at Camp Delta. It’s difficult to tell whether the use of the verb “drenched” is a writer’s flourish or the result of careful, firsthand observation.

↩