In retrospect, the Sixties seem a decade in the life of this country during which some cellar door was left ajar. Suddenly loose and rampant in the house were all manner of trolls and intruders, manic apparitions, a dark ransacking beserkness from the chaos of the old night outside. With the assassinations of King and the Kennedys, the advents of Wallace and Agnew, the mounting mad incantations of White House rationales for Vietnam, and such sorceries as Nixon’s self-wrought exhumation and reanimation, those ten years passed like a malarial dream in which the unthinkable became the familiar, the surreal became the commonplace.

It may seem, then, a reckless proposition, but there was perhaps no more astral occurrence during that long phantasmagorical decade than the ascension of Lester Garfield Maddox—erstwhile fried chicken peddler and pick-handle Dixie patriot—to the governorship of Georgia. He was, in a way, the consummate caricature of those awry times. The nation’s only notice of him up to then had been a single brief glimpse, in the summer of 1964, of a flushed, bespectacled figure with a scanty-haired onion bulb head lunging gawkily about the parking lot to his Atlanta restaurant, a small black pistol clenched at his waist, shrilly shooing back into their car three black students who had presented themselves as customers. The next time everybody saw him, not quite two and a half years later, he was being inaugurated governor of Georgia.

That was in 1966. Elected in 1970 to the lieutenant governorship, he presides now over the parliamentary machinations of the state senate, invested with the gravity of a true and formidable political heft in the state, posing with an almost Presbyterian soberness and decorum on that chamber’s rostrum behind sprays of tiger lilies and gladioli vaguely suggestive of the floral gorgeousness embellishing the pulpits of Billy Graham crusades, and serenely biding his time until, in all likelihood, he is elected governor again in 1974. In spite of all his consequence, the passage of six years has done nothing to diminish the initial incredulousness among a lot of people in Georgia.

Nevertheless, as has become an official tax-subsidized courtesy for governors at the conclusions of their terms, the Georgia Department of Archives and History has produced a solemn bound volume of Lester’s assorted public ruminations while he was occupying that office. This could not be considered exactly one of the more imposing events of the publishing year. The truth is, at no time during his tenure did Lester really amount to anything more, in the course of the state or the country, than a grotesque entertainment, and this compendium of his various contemplations, by any ideological schema yet intelligible to man, simply refuses to scan. It is a transcript of four years of exuberant static which, however, understates the complexity of that static, since Lester has acknowledged he almost always improvised on these texts. What’s more, Lester does not translate well into print: his pronouncements are lacking in the singular sound of his voice—that high tinny hectic whanging, urgent and helter-skelter, losing with no more trace than a lisp whole syllables, leaking tight little whistles of air now and then—which is like the very sound of slightly zany irascibility.

Still, however remote this collection of texts may be from the true nature of the man, it does provide occasion for reflections on Lester—not an altogether bootless exercise, as it turns out: one discovers that, while he has endured as one of the more garish curiosities in recent American political lore, his appearance was attended by larger implications and portents, even though he has remained cheerfully innocent of them, and his governorship may have meant more than most, including Lester himself, suspect.

Until almost the very instant of his election, alien journalists visiting Georgia were baffled that Lester could be taken with any seriousness at all in the state—even after his celebrated little pick-handle Armageddon with the three black customers at his restaurant. There were, actually, several skirmishes at his place, The Pickrick: Lester on one occasion cawing at two black students seeking entrance, “You no-good dirty devils! You dirty Communists!” and another time, merely standing in his doorway with a forefinger thoughtfully rummaging in one nostril as he watched his two stout sisters, on a street corner twenty yardsaway, demand of another delegation of young blacks, “Have you boys been born into God’s family? Have you been regenerated?” But aside from that, about all he had for political currency were his weekly Atlanta newspaper ads, composed in a festive conglomeration of type faces resembling a carnival poster, in which he alternated menus with some of the more ambitious segregationist billings gate of that day, propounding every noticeable political figure in the state and nation to be a “coward…no-good dirty bum…rascal.”

Advertisement

At the same time, he was a more or less compulsive campaigner for office, even managing to get into a couple of runoffs, one for mayor and the other for lieutenant governor. During this time, Lester once mused in mild bewilderment to a reporter, “You know, I been sending President Johnson telegrams ever since the Civil Rights bill was signed—the last one I sent cost me thirty dollars. But you know what? He’s never answered a single one of those telegrams. Nossir!” Whenever the state legislature was in session, he could be found in the capital’s corridors—a solitary urgent figure—eagerly handing out patriotism tracts and small tin lapel-flags. The young doorkeepers to the legislative chambers were notified they would be fired for only two reasons: “Layin’ down on your job, or if you ever let Lester Maddox get past you and loose in here.” Also, he could usually be depended on to show up at all the rowdier racial confrontations around town. There was something about him evocative of the distraught gentleman in the Philadelphia Inquirer cartoon ads.

Raised the son of a steelworker in one of Atlanta’s smoky downtown neighborhoods, married at nineteen, variously employed in a steelyard and then in a plant near Atlanta which produced the bomber that dropped the first atomic bomb, entrepreneuring chicken farming for a while (“That didn’t work out, ’cause they get involved in this cannibalism, you know”), desultorily diverting himself with baseball (“The other boys used to make fun of me ’cause of me bein’ near-sighted. They used to call me ‘Cocky’ ’cause of my eyes”), Lester himself reflected rather accurately in one speech that “if anyone ever had a perfect background for failure, I did.” Nevertheless, he possessed that peculiar fortitude, that ferocious fidelity to purpose, that is sometimes one of the integrities of absolute hopelessness. He had the serene fierce dauntlessness of those indefatigable Isaiahs in rumpled gabardine seen on downtown street corners. He was impervious to embarrassment, invincibly chipper. There was a special sort of heroism about him; he was something like a cracker Don Quixote.

But the truth is, Georgia—along with its neighboring neo-Confederate states—has long been familiar with the arabesque and fantastical in its political dispositions. In its deeper southward drifts, American politics has always tended to take on the gaudier hues and flourishes of transactions in those palmy Latin republics just a little farther to the south. There was much about Louisiana in Huey Long’s day, for instance, that seemed closer to the customary style in Tegucigalpa or Santo Domingo than to the regulations drawn up in Philadelphia. In Georgia, there have periodically occurred events like the time young Herman Talmadge, after his crimson-suspendered daddy Gene expired before he could assume the governorship again, simply occupied the capitol building with his partisans one drizzling winter twilight in what was by almost any calculation a full-blown putsch. Perhaps the most eloquent testimonial to the magnitude of Lester’s political implausibility is that, even in this theater of politics, he was dismissed as a whimsical eccentric.

Lester himself liked to recount, after he had delivered himself into the governor’s office, that “I never doubted for a second I would win. All I had to do was beat the state Democratic party, every major labor leader, the state Republican party, all 159 courthouses, about 400 city halls, all the politicians of rank—every one of them—every major newspaper, the television and radio stations, the railroads, every department store, all the major banks, all the major industries, the utility companies. So that’s what I did. I beat everybody!” With a campaign staff which consisted of himself, his wife, his daughter, and one of his sisters, he mailed out 50,000 copies of his platform and then simply vanished into the Georgia interior, driving a grimy white 1964 Pontiac station wagon with a four-foot ladder tied to the top. Before long, one began to notice along remote roadsides a spattering of small cardboard signs, tacked to telephone poles and pine trees, announcing in simple black print, THIS IS MADDOX COUNTRY—MADDOX WITHOUT A RUNOFF.

Later Maddox explained what he had brought to pass, way out there in the state’s outback, by informing audiences, “God was my campaign manager.” If so, He additionally intervened through some intricate sleight of hand with the state’s political processes. Maddox’s actual transmogrification into governor was accomplished—somehow fittingly—through a prolonged dreamlike slapstick sequence of political pratfalls. He never did win a popular majority in the state. Instead, with a diffusion of candidates in the Democratic primary, Lester emerged, through the capricious lottery of plurality selection, in a runoff election with a former governor, Ellis Arnall, an aging but still gusty liberal from the New Deal days. Now having to choose,in those slightly delirious times, between Maddox and this affable Roose-veltian relic, primary voters opted for Lester—thus nudging him to a headier exaltation than he had ever enjoyed in his life. But it didn’t really seem to matter, because the Republican nominee was Congressman Howard “Bo” Callaway, a doctrinaire conservative and segregationist of the more abstract and elusive variety, whose popularity in the state was awesome and virulent.

Advertisement

The millionaire scion of a Georgia textile dynasty which for decades had been unobtrusively presiding over a sizable area in western Georgia of pines and broom sage and buzzards, a tall trim former West Point cadet with a bright choirboy’s face and tight little mouth and chastely barbered hair combed straight back in the lacquered style of the Twenties, Callaway could not seem to believe his good luck when he found he would be facing Lester in the general election. Not the most complicated of men himself, Callaway began campaigning ebulliently and breezily more or less on the issue of school spirit—“I love my Georgia,” he kept assuring everybody.

One state legislator proposed at the time, “Hell, neither one of ’em would know how to pour piss out of a boot. Callaway might, if the directions were printed on the heel and he had to turn it upside down to read them.” At any rate, the thought seems never to have occurred to Callaway that the people could really be serious about Lester. As it turned out, the majority of them weren’t. But there began to gather, among those liberals and moderates in the state appalled by the prospect of either Callaway or Maddox, a write-in movement for that venerable New Deal governor who had been discarded in the Democratic primary runoff. As Callaway now regarded the spectral possibility this posed—that neither he nor Maddox would wind up with a majority, which meant the decision would be pitched into the Georgia House, mostly inhabited by gristled glandular Democrats hardly disposed to elevate a Republican to anything, whether he was Callaway or not—there began to grow in his eyes a blank stricken suspicion of disaster.

All along, as supplement to his campaign of congeniality and hygienic Jaycee-style wholesomeness, Callaway exhibited a singular, McNamaran faith in the Delphic powers of computers, and his headquarters, according to one visitor, “looked like the War Room of the Strategic Air Command.” But to the end, Callaway seemed as incapable as his computers were of entertaining such aberrations as the spoiler psychology.

The general election, in fact, ended inconclusively, with nobody clearing a majority, though Callaway did pull a plurality, well outdistancing Maddox. But on the very ominous eve of the House’s dispensation, Callaway was still effusing to a gathering of Jaycees in an Atlanta hotel, with Lester himself also on hand, “Gee, it’s so good to see all these familiar faces, I want to tell you. Yawl have worked so hard during this campaign—gee, you know, I still remember yawl riding those motor-scooters around in the rain down there at Jeckyll Island, why goodness—all of you out there who’ve worked with us so long and so faithfully, just raise your hands a minute so I can see….” He then became, momentarily, squintingly earnest: “You know, a lot of people through this campaign have told me, ‘Oh, Bo, you can win this election if you’ll just compromise a little bit.’ Well, I told them, well, maybe so. But I’m not going to change these principles of mine just in order to solicit votes. Because I love my Georgia….”

There was a plaintive urgency in his voice as he repeated this news one more time, as if he felt he had somehow not managed to convince everyone—if only he could get it across to them everything would be different, everyone would see and the whole thing would turn out properly after all. He reminded them that the punishment of an apathetic public “is to live under the government of bad men.” At this allusion, the polite and genial grin Lester had been maintaining abruptly vanished, and he cast a long sober innocent look up toward the ceiling, his hands folded thoughtfully under his chin. When Callaway finished, there was a spirited booming of cheers and applause, but Lester, in the midst of it, simply grinned at nearby reporters, lifting his eyebrows briefly, slyly, and began tossing peanuts from his cupped hand into his mouth.

At the capitol the next morning, there was a certain giddiness in the air, as if everyone had suddenly found himself caught in a colossal prank too outrageous and ingenious and enthralling to interrupt. During the preliminary formality of retabulating the popular vote, ballots from the far folk precincts of the state were reported for Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, the University of Georgia’s football coach, and “miscellaneous local individuals.” Finally, in the early evening, the legislators anointed Lester Maddox Governor of Georgia.

Lester had been downstairs throughout the day, listening to the proceedings on the radio. As soon as the business was concluded, he and his attendants, along with a praetorian guard of state troopers, surged upstairs toward the governor’s office to be sworn in before any unanticipated intervention. It was a startling stampede—as if some whooping yodeling many-limbed monster suddenly were charging amuck through the corridors of the capitol—and as it brawled on up the marble staircase to the capitol’s main floor, one had a sense again of being in the middle of some Latin American midnight coup: there was about it the definite, if gratuitous, air of attack, rush, strike.

Absorbed in a furious urgency of its own, this stampede was completely at odds with the absence of suspense in the proceedings in the House chamber which had birthed it and released it. It was as if Lester’s own sense of theater demanded that all his solitary years of struggle be, finished in this melodramatic style, even if it were a storm in a vacuum. The troopers—in their broad-brimmed Scoutmaster hats evocative of the Italian military police in A Farewell to Arms, called “airplanes”—carried Lester along in the melee, buoying him up with their hands under his shoulders so that the tips of his shoes just occasionally grazed the floor. In their midst, Lester himself had a vague and befuddled glaze behind his spectacles, a half-smile faltering on his face.

After Maddox’s quirk-victory in the primary election, that old thorny redoubtable Elijah of the Southern conscience, Ralph McGill, the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, tollingly invoked passages from Ecclesiastes in a column about “a dog returning to his vomit.” Some time later, he confessed to a friend, “I am an old man, and I’m not sure of anything any more.” But in many other quarters, including liberal ones, the advent of Lester occasioned a kind of perverse glee—something had happened outside the computations, the credulity, the comprehension, even the imagination of the press and the political assessors and brokers. A primitive, unaccountable event—something more alive than all analyses—had come to pass, astonishing the most meticulous anticipations. It seemed, for a while, an exhilarating reminder that the common custodians and bookies of reality own, at best, only an illusionary approximation of reality; that life is, after all, larger than all arithmetic. But this mad elation was soon followed by more sober reflections: “My God,” noted one Atlanta editor, “we still got us a little ole state here that’s got to get through the next four years somehow.”

Lester’s initial announcements were not enormously heartening on this point. Beyond simply reassuring everybody that “I am tremendously proud and happy to be Georgia’s governor,” he confided right after his inauguration, “Christopher Columbus found a world and had no chart except his faith in the skies. It is with that same…faith…that I stand before you as your new chief executive.” In view of his past, the prospect of Lester’s conducting the whole state through the next four years according to his own private communions with the sky profoundly traumatized, among others, the state’s establishment, political and economic. The night he was sworn in, he proceeded to the House chamber, delivered a brief address, and then, not unlike a drowning man, began grasping for the hands of everyone within sight—including newsmen—while he implored, “I’m gonna need yawl to hep me now. I’ll be good to you, and you boys be good to me, henh? Hep me be a good guvnuh now.”

Watching him even Georgia legislator Julian Bond was moved to speculate, “You got the feeling he’s suddenly realized he’s an overwhelmed man, and he does want help bad, because he’s already begun to wonder if what he’s been thinking was right all these years is really right.” Almost immediately, that array of proprietorial interests which he had so stunningly outflanked in his campaign—the banks, the state’s political consortium, all the patriarchs of the conventional respectability—undertook, with a certain muted desperation, to amiably assimilate him, with the hope of thereby neutralizing him. They cheerfully volunteered advisers, consultants, aides, speechwriters. Poignantly, Lester seemed not only receptive but euphoric over the offers.

Indeed, from his first speeches, one gets the sense he was rather awash in mellow surfs of gratitude, dolphining through hitherto unknown Gulf-tides of indiscriminate magnanimity. In his inauguration speech, he delivered himself of such improbable phrases as “respecting the authority of the federal government…no place in Georgia during the next four years for those who advocate extremism…do not want to see a single school closed…room enough in this great state for every ideal and every shade of opinion…for the right of dissent as well as the right to conform…Georgia belongs to every citizen.”

As his voice went on in thin electronic shimmies over the throng of his supporters their applause became broken, disconcerted, short-winded, and one had a fleeting suspicion that maybe Lester’s mike was disconnected, that he was moving his mouth but, through some sly act of rewiring, the voice was actually that of an impersonator crouching somewhere below the platform—an infamous trick, a far more fell conspiracy than the extravagant theatrics of assassination alarms advertised in the capitol the night of his swearing-in. It was a kind of assassination for which Lester’s retainers had not been prepared.

This impression lingered on through the following weeks. Someone seemed to have dialed him out of focus. His appointments to the state party executive committee were agreeably conciliatory and eclectic, because, he explained, “From the very beginning, the Democratic Party has drawn its members from all segments of society and has derived its strength from the diversity of its membership…. Its greatest victories have come when its members have exercised tolerance for their differing views on specific questions….” All these placable sounds prompted Wallace, over in Alabama, to snort finally, “Hell, what’s wrong with Lester, he ain’t got no character.”

What Lester lacked was not so much character as any ideological coherence. He operated from a political sophistication of about the subtlety of a cross-stitched sampler homily, and about as free of tangible details and applications. (He once proposed, with a canny wink, “You know, Goldwater would have won that thing in 1964 if it hadn’t been for Fact magazine. You know—that Fact magazine, that comes out with all those articles? They beat him when they came out with that article on Goldwater, and had that diagram of all that stuff comin’ out of his head.”) The state’s proprietors soon determined that there was really no need to neutralize Lester: his own essential, irredeemable ineptitude precluded his impinging seriously on the state’s affairs in any way whatsoever, either benignly or disastrously. He was as incapable of effecting anybody else’s notions as he was his own.

His state-of-the-state messages were given to such pronouncements as “One strong, fearless, dedicated, and God-fearing patriotic legislature can do the job and return America to its rightful place as the greatest, freest, and cleanest nation on earth.” But when it came to the particulars of executing such propositions, Lester allowed that “there just isn’t much major legislation left to pass these days.” At times, when the fancy struck, he did dispatch proposals to the legislature, but by the close of his first year in office, he had already lost more bills than his predecessor had in four years.

As a result, the magnetic field of authority around the governor’s office began to fade conspicuously. Satellite agencies in the state’s government started scattering off into their own separate orbits—most notably, the legislature. Georgia survived Maddox largely because of his inability to effectuate any of his notions, but the discovery was made in the process that the state could run itself without any governor’s office at all: a realization that immeasurably diminished that position. To his successor, moderate Jimmy Carter, Maddox left an office as sacked of its engines as Atlanta after Sherman’s passage.

About midway in his term, Lester declared to a congregation at Adair Park Baptist Church, “For many years, it was my ambition to be a preacher….” And, indeed, it seemed that he considered he had been assigned not so much to legislate and administer as to act as a kind of full-time lay chaplain to the state at large, conducting a running four-year-long revival for “honesty, efficiency, and morality” in the business of the state. Accordingly, Lester plunged back and forth over the map of Georgia in a performance—1,200 speeches, twice his predecessor’s log—that, as one looks back over it now, resembles a marathon pinball-machine game: a ceaseless pinging and chatter of pique, exuberance, prophecies, commentaries, as he propelled himself among such locales as the Warner Robbins Church of God, the Hormel Company’s Tucker plant, the Phillipi Baptist Church of Locust Grove, a new softball field in Cedar-town, a Congregational Holiness Youth Camp, a Dunlop Tire and Rubber Company plant, a Penny Catalogue distribution center, the Macedonia Baptist Church.

His appetite for audiences seemed inexhaustible, omnivorous: he appeared for the Seminole County Fat Cattle Show, the Jeckyll Island Easter Egg Hunt, the Sweetheart Plastics plant dedication, the opening of Horne’s South Motor Lodge, groundbreaking ceremonies for the Lovable Girdle and Brassiere Company, the Hard Labor Creek golf course dedication; he spoke to such assemblies as the Graduate Embalmers of Georgia, Inc., the American Turpentine Farmers Association, the Scientific Glassblowers Society, the National Association of Hairdressers and Cosmetology, the Hot-Dipped Galvanizing Association, the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery.

On the whole, any effort to parse some controlling political dialectic out of the effusions of this epic circuit becomes a flirtation with lunacy—it is a voyage through unsuspected outer galaxies of daffiness. While insisting heatedly that “perhaps the greatest of all freedoms is the freedom to criticize…and never have there been greater pressures to…silence dissent,” he could also blithely and unblinkingly add that “any rights to be protected are those of peaceful and law-abiding citizens”—as distinguished from “letting this great, beautiful, hard-earned country be spoilt, spit upon, desecrated, and dominated by a bunch of snotty-nosed, stringy-haired, red-eyed, LSD-taking younguns who range in age from thirteen to eighty.” Reminiscing once about his own private pistol-brandishing demonstration in the parking lot of his restaurant, he proposed, “I was fighting against legislation which was contrary to the United States Constitution,” but he also maintained, with equal ardor, “I do not think anyone has the right to decide which laws he will or will not obey, or to engage in acts of civil disobedience.”

Oblivious to such dissonances, he was also frequently given to diverting bogglements like his suggestion to a Calvary Baptist Church, “If Hitler could poison one generation of Germans and nearly become dictator of the world—if Stalin could poison one generation of Russian communists and enslave over half the world’s population…think what one generation of Americans, completely committed to Christ and God, could do for our country and our world.”

Over all his utterances there seems to preside the watchful shade of some sixth-grade history teacher in Lester’s childhood, a prim and righteous spinster with her hair in a bun who provided him with lifelong DAR revelations about patriotism and the American system—to which were later added the perspectives of a conglomeration of incidental extractions from Edgar A. Guest, Billy Sunday, William Jennings Bryan, Paul Harvey, Douglas MacArthur, and The Reader’s Digest. His divinings, not only of world affairs but of such social distress as crime and poverty, were of the old-fashioned sawdust-tent-revival variety: “There is no more effective way to rehabilitate lost men than by introducing them to God,” he announced, and “We cannot expect the world to be righted until men get right with God…. I believe a mighty spiritual Holy-Ghost revival inour land would do more in one day to solve our problems and make us secure against our enemies than all the conferences, deliberations, and treaties of politicians could do in a hundred years.” At one National Governors’ Conference, he later reported to the folks back at the Glenhaven Baptist Church.

I asked the other governors to stand up for God by signing this statement: “Now, therefore, be it resolved, that we of this National Governors’ Conference rise to personally and collectively draw nearer to God, and…by regular deed and daily example, provide the spiritual leadership for which our people hunger and which God demands…to heal this great land….” Now, I know you’ll find it hard to believe, but a few of the governors at the conference didn’t want this resolution to even come up for a vote. Fortunately, the majority of those present did vote to suspend the rules and let the matter come up for a vote, and…the resolution was adopted as a policy statement…but I still can’t get over some governors voting against it.

In fact, one sometimes has the sense that Lester strolled directly and bodily out of the more baroque fantasies of Sinclair Lewis. “The goals of…reaching other businessmen for Christ,” he once propounded, “are purposes which I have been promoting all these years…in real estate, sales, the food and furniture business…. The American free enterprise system could never have been established if it were not for the birth of Christ…. The Christmas trade alone is an example of this truth…. In His name, more activity is promoted, more gifts are bought and wrapped, and more business is advanced, than in any other name in the Yellow Pages of the telephone directory. There is power in the name of Jesus!”

At the same time, even while affirming that “I’m a segregationist and proud of it,” he appeared deeply scandalized by the furor raised by black congressmen over his distribution of souvenir pick-handles in a Capitol cafeteria one afternoon—to Lester, it evidenced an appallingly petty malevolence on their part. He simply could not understand why they should have taken umbrage. He was, on the whole, blandly capable of towering tackiness and tastelessness. After the assassination of Martin Luther King, he felt impelled to protest,

My heart went out to Mrs. King and her four children…[but] my heart was heavy too when I thought of the wives and children of the firemen, the policemen and the innocent bystanders who have died, and will die yet, because lawlessness has been sanctioned and financed…. I did not weep at the death of Dr. Martin Luther King…. Tears are not shed for the dead…. I felt no need to do penance, for I had done Dr. King and his followers no wrong…. And I say to these people…feel free to criticize Governor Maddox…as Reverend King criticized me, for I will be critical of you too. I will criticize you when you condone lawlessness and attempt to justify riots, looting, burning and murder…when you interpret every “wish” as a God-given right.”

A few weeks later, somewhat more succinctly, he sniffed, “We have seen representatives of the White House, would-be Presidents, and other leaders weeping and flying all over the nation to mourn the death of agitators who publicly threatened to overthrow the government.”

Of course, the grim question Lester prompts in all this is how characteristic such myopic meanness might actually be of the perception of the general citizenry about the times in which they are involved. As for Lester himself, shortly after his inauguration he began advertising certain speculations about enlarging on the trick he had managed to bring off in Georgia. “Maddox Country has already extended halfway through South Carolina and clear to Miami,” he averred, and then he availed himself of a Fourth of July appearance to submit, for everyone’s somber consideration, “a recent article by Jeane Dixon,” the nationally syndicated astrologer. A particularly voluble admirer of Lester’s, Mrs. Dixon, Lester now portentously disclosed, had said “that she sees, and I quote, ‘resentment and anger building up in the American people. They are searching for a new personality who will act, not react…show courage, not fear…and who above all will hold high the torch of freedom for the world to rally around…. This personality,’ ” Lester recited on in awe, ” ‘is trying to emerge, and he will be forced to the forefront by the American people. Events are building in his favor….’ “

A little more than a month later, in what was unquestionably the consummate moment of whackiness in Lester’s four-year governorship, he announced himself a candidate for the White House. He seems to have presented himself a bit before Mrs. Dixon’s events had finished arranging themselves for him. The annals of American politics, in fact, probably hold no more curious scenario than Maddox’s two-week Presidential adventure. One Atlanta newsman who was close to the governor through it all was asked if it had occurred to Lester at any point that his possibilities might be something less than momentous; the journalist replied, “Look, you suddenly find twenty secret service men following you around everywhere you go, and you don’t have any trouble beginning to believe it’s for real.”

After an overwhelmingly unnoticeable collapse at the Democratic Convention, and his entourage of bodyguards had vanished back into the air as magically as they had appeared, one might suppose Lester—who liked to attribute his governorship to “Dale Carnegie and prayer”—would be left with the suspicion that, at times, there are limits to what even Positive Thinking can bring to pass for a man. Since then, though, he has observed that, with Nixon and Agnew in ascendancy, he also enjoys considerably greater fashion: “It has become respectable to be a conservative. A broadcasting executive in Atlanta…dared to go on television and actually use the word ‘communists’ when talking about planned riots in Chicago…. Isn’t that wonderful?”

It’s unlikely he’ll offer himself for President again. But, as one capitol reporter declared, “Lester operates by auguries. Driving down here some morning, he might see a damn mockingbird on a lawn, and when he gets to his office, he’ll announce he’s gonna run for President again.” In any event, since his accidental carom into the governor’s office, Lester has prospered. Beyond all conjecture, he has increased, if not visibly in wisdom, certainly in stature, and in favor at least with the inhabitants of Georgia. He won his lieutenant governorship by a lavish margin, and in a recent poll of a Georgia municipality, 80 percent approved of the style in which he had comported himself as governor. Not long ago he even retained former governor Carl Sanders—an urbane prince of the establishment who during his term had once fumed in the privacy of his office, “I’m not about to let the fools and nuts like Lester Maddox take over this state capitol for a while yet, I can tell you that”—to represent him in a lawsuit over infringements of his exclusive right to manufacture and peddle his Lester Maddox wrist watches, part of the commerce he conducts in similar items like Lester Maddox sweatshirts and “Wake Up, America” alarm clocks from a small shop among Atlanta nightclubs and boutiques.

In a sense, the political weight he now carries in Georgia might seem, among other things, unsettling proof of the extravagant commitment to a peculiar sense of humor on the part of that state. The truth is, there still lurks in the Southern nature—the South having in many respects lingered nearer the frontier longer than any other region of the country, including the West—a celebration of unruliness and mayhem, a secret gleeful readiness, like the spry whinnying whanging of a jew’s harp, for the rowdy and anarchic. It is hardly the most responsible of political inclinations, but the delight Lester still gives many Georgians is a delight in an earnest, impassioned, irrepressible poltergeist.

During one of the affrays at his restaurant, when police had barricaded traffic at both ends of the street, Lester stalked from one corner to the other, shrilling at the officers, “You blockin’ my customers! Listen to me—shut yo big mouth, and listen!” and was trailed at his every move by a cheering throng of some 500 people in the warm August evening. He was like the mayor of some small provincial French village who had audaciously taken it on himself to flamboyantly, if hopelessly, defy in the town square the forces of Paris’s officialdom, accomplishing in the end no more than a magnificent traffic jam. But the crowd yelled happily anyway from the sidewalks, “Attaway, Lester! Oh, man—whatta man!”

Lester once explained himself, probably more conclusively than anyone else ever has, when he described his boyhood to an Atlanta PTA group:

I can remember how faded blue-jeans and worn-out shoes didn’t seem too important when the schoolday was begun with the reading of a verse from the Bible, reciting the Lord’s prayer, and saluting the flag of the United States of America. For a few minutes each morning, I was somebody special. I was Lester Maddox, an American…. I sincerely believed that if I saluted that beautiful flag, [it] would extend its blessings to me…. My inspiration came from every street corner where a small grocery store or a shoe shop or a drug store was located. I saw men standing in the doorways of their businesses in the early morning, and their faces reflected contentment and pride and security. I wanted to be like them. I wanted to be able to stand in my own doorway and greet the schoolboys as they passed by…. My dream came true. I was Mr. Maddox. I was Mr. Pickrick. I was Mr. Somebody.

On more than one occasion, Lester has betrayed such egalitarian sentiments as “democracy is founded on the belief that there exists extraordinary possibilities in the common man.” Of course, ranged against such Populist figures in the South as Tom Watson or Huey Long or even George Wallace, Lester is rather a dimestore trinket, a kind of Dixiefried Jester—he simply lacks the political savvy and viscera to count for more. But there is no doubt that, however mixed his bag of notions now, he derives fundamentally from the Populist sensibility. During one of his earlier campaigns, he was always dismissing Atlanta’s silvered establishment mayor, Ivan Allan, as “The Peachtree Peacock,” flourishing a pair of silk socks in the air as he did. Before long, that informal board of proprietorial parties in Georgia recognized that not only was there no need to neutralize Lester but they would have had a stubborn time of it if they had tried. “That group in Atlanta,” Lester crowed, “seems to think that local government should be run from Atlanta’s city hall, their local newspaper office, and the offices of the financial czars downtown around Five Points.”

Nevertheless, Lester finally presents a glum corporal cartoon of the Populist temperament’s susceptibility to lurid aberration, to self-aborting mutation. “One problem with Populism,” says Emory University political scientist James Clotfelter, “has always been that the people who speak for it tend to be very unsophisticated and naïve to begin with. Their perspectives are those of people who have grown up on the periphery of power, which leaves them somehow especially vulnerable to corruption.”

Another shrewd Southern observer, the gospel minister Will D. Campbell—a veteran civil rights movement conciliator now working as an emissary to Klansmen—maintains:

In a sense, the real victims of the system in the South, of the racist mentality, have been the poor whites—the rednecks, urban and rural. They’ve had their heads taken away. The system got about everything else from the black man—took his blood, took his back, took a portion of his spirit maybe—but it never managed to get his head. All along, he’s known what was going on. But the redneck, he’s never known who the enemy is. He’s never known what’s been hitting him. Throughout the course of Populism, every time the poor white began getting together in a natural alliance with the equally dispossessed black, every time he’s started to make a push to bring a fairer equilibrium into the system, the ones riding on top of him—the reigning establishment of the day—have told him it would mean blacks were going to ravish his wife and his daughters, and the Bolsheviks were going to invade the courthouse. He’s never known how he’s been had.

Lester’s particular vulnerability, it appears, was that lonely childhood desperation to be “Mr. Somebody”—which itself was defined according to the pinched rectitudes of a popular ethic cultivated by the system. In fact, the American custodial estate’s long, resourceful, and assiduous diversion of each surge of Populist politics—not only through various intimations of racial and Marxist menace but also through the beguilements of the Horace Greeley romance and Saturday Evening Post respectabilities, and not only in the South but in instances throughout the country which are remembered by other names, like the IWW—constitutes perhaps the most enormous bamboozlement in all archives of political cozenage.

Lester himself is only an ephemeral and tawdry casualty of this. While declaring with genuine passion that “one of the great tragedies of our times is that the people’s voice is far too weak and too often falls upon deaf ears,” nevertheless, like so many others before him, he is impossibly enamored of those stingy pieties and musty orthodoxies by which, historically, the people’s voice and interests have always been distracted. “This administration believes in less government in business and more business in government,” he could proclaim, and “our nation became the greatest on earth not because of big men in government, but because of big men in free enterprise.” Also, characteristically, he showed a somewhat exorbitant deference to the awesome irrelevancies of the military glamour; addressing the Gray Bonnet Regiment of the Georgia National Guard, he enthused, “I wish all Georgians could have seen your mounted review this afternoon, and the powerful pieces of armor and other equipment. It certainly has heartened me to see such tremendous power…to know that our state has sufficient force to deal with any enemy….”

Nevertheless, if one ignores his clamorousness and gaudy posturing—admittedly no small feat—Lester assumes, in spite of himself, an aspect markedly more wholesome, for instance, than that of Wallace. This may be largely owing, of course, to his essential simplicity of heart and wit. But throughout his tenure, though always clangoring the more squalid homiletics of the right, he seemed compulsively to lapse into genuinely generous and expansive gestures. Most notably, he introduced by appointments a substantial and unprecedented number of blacks into the middle levels of state government—nowhere near proportionate to their percentage of the state’s electorate, but a meaningful increase nonetheless. For all his baleful fulminations on crime and punishment, he seemed given to an unusual solicitude for the state’s prison inmates, delcaring once to the legislature, “Georgia, unfortunately, was one of the last…to lay to rest the infamous ‘chain-gang’ concept of corrections with its philosophy of vindictive retribution…. We’re going to begin anew, if that’s what it takes, to have a system which helps inmates shape their futures, rather than reminding them of their pasts.”

His disposition in this regard has been sometimes ascribed to the fact that his own life has been touched with a similar melancholy, one of his sons having been arrested on more than one occasion for burglary. Whatever the reason, he initiated a policy of early probationary releases for a sizable portion of the state’s prison inmates—“a second chance,” as he put it in a damp voice, “for those…who, for one reason or another, have left the path.” Accordingly, he admonished graduates of one police academy, “Never allow yourself to regard those you are forced to correct as adversaries or enemies.” Not surprisingly, he became in time, for most of Georgia’s prison population, their patron saint, and one escapee turned himself in to Maddox at the governor’s mansion with a list of grievances he had been delegated by his cellblock mates to bring.

This occurred on “Little People’s Day”—those Sunday afternoons, scheduled by Maddox at regular intervals, when he simply threw open the front door of the mansion to anyone who wanted to wander in and chat with him. The same expansiveness, to a certain degree, prevailed at the governor’s office at the capitol. “There have been more visitors to your governor’s office and the governor’s mansion in the past two years,” Maddox claimed, probably legitimately, “than in the past quarter of a century.” At the same time, though he was sometimes seized by such fits of peevishness as ordering all newspaper racks from the capitol grounds, he was generally quite sporting about the press’s frequent raids on him, gamely allowing, “No matter how bitter, no matter how cruel, and no matter how unfair the editorialist’s pen is to me, personally, I would sacrifice my career, my fortune—yes, even my life—to keep this symbol of freedom alive and unchained…. The small pain which I suffer on occasion…is a bargain price to pay for that….”

He was given to other endearing and refreshing impulses. Any rumors of regular folk anywhere being hoodwinked, exploited, or bullied instantly inflamed him. He mounted a number of vigilante ambuscades on reported clip joints, and once erected, at both ends of a town legendary as a speed trap, personally autographed billboards notifying tourists of that fact, with highway patrolmen stationed beside them to guard against their removal by town authorities. A group of citizens appealed to him from one desolate little southeast Georgia county which had long been the private dukedom of a courthouse coterie. Lester’s energetic intervention landed him in some embarrassment when it was discovered that the minister leading the dissidents happened to trail behind him a somewhat murky, lavender-tinted past—a mishap that, nevertheless, seems to have done nothing to dispel Lester’s sublime obliviousness to the possibility that life might become a bit more complicated than the primary colorations of Sunday School didactics.

But beyond all this, Lester’s mere political arrival was, in itself, the first tentative assertion of a gathering popular mood which was ultimately to dislodge those arrangements of power which had customarily been managing the fortunes not only of Georgia but of other Southern states: that phenomenon which has been called the emergence of the new Populism, and which actually has been exerting itself beyond the South. Lester no doubt still remains impervious to this. But often the imminence of new political seasons is first signaled by the appearance of such unlikely errant birds. Not long after Lester’s election, Sam Massel, a Jew, ran for mayor of Atlanta and confounded the genteel collection of enlightened merchants accustomed to directing the city’s affairs through a succession of proxy mayors when he defeated their newest offering, a Republican, with his own coalition of blacks and blue-collar unions.

Though Lester was not the only one who didn’t suspect it at the time, what he boded, suggests James Clotfelter, were the recent elections of the widely advertised new-direction governors in the South, like Georgia’s Carter and West of South Carolina and Waller in Mississippi. “Callaway, back when Lester was taking him on, symbolized the kind of guy who’d always gotten elected in Georgia. The same way, all these new governors just weren’t the proper kind of guys to be elected the way it’d always been up to then. They worked it outside the old familiar structures. But what Lester did, he told everybody—anybody—they could do it.”

Curiously enough, then, Lester has probably had something of a renovating effect on the democratic process, if not directly elsewhere, at least discernibly in Georgia. With some authenticity, he maintained, “Behind closed doors you throw your politics and your weight around, and people don’t get to see what’s going on. But at least I’ve opened those doors. Let them see the bad when it’s bad, let them see the bad as well as the good. Maybe it doesn’t work every time to my advantage, but how can I get the people involved if I hold things behind closed doors? Talk about the advantage, instead, of what I promised the people—honesty and efficiency in government, and open government. And after I’m governor, what’s gonna happen? What’s the next governor gonna tell the people when they come knocking at his door on “Little People’s Day’? What’s he gonna tell the news media who’ve felt free under this administration to look and look hard, hit and hit hard? They won’t be able to kill it all. And you can’t tell, if this could happen maybe with every third or fourth governor, it could keep living, keep on living.”

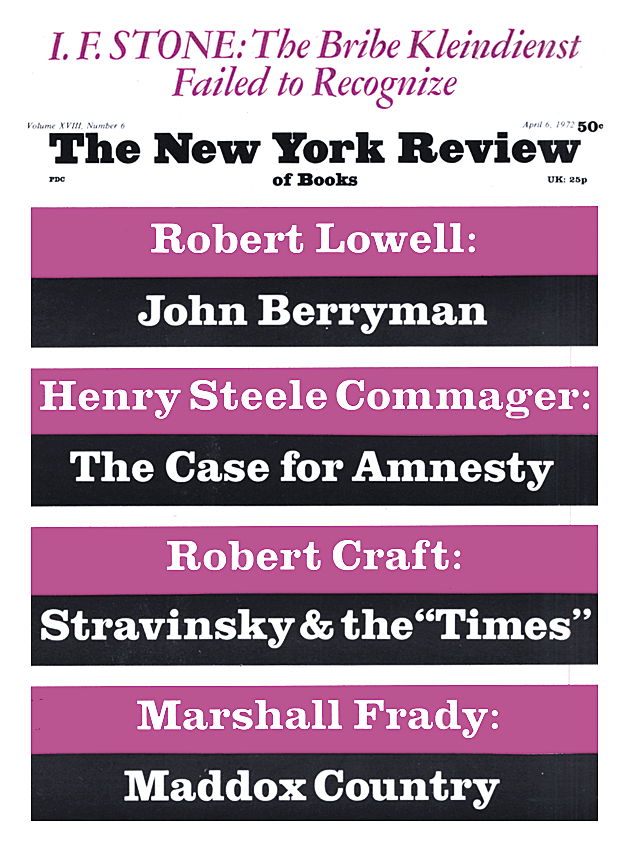

This Issue

April 6, 1972