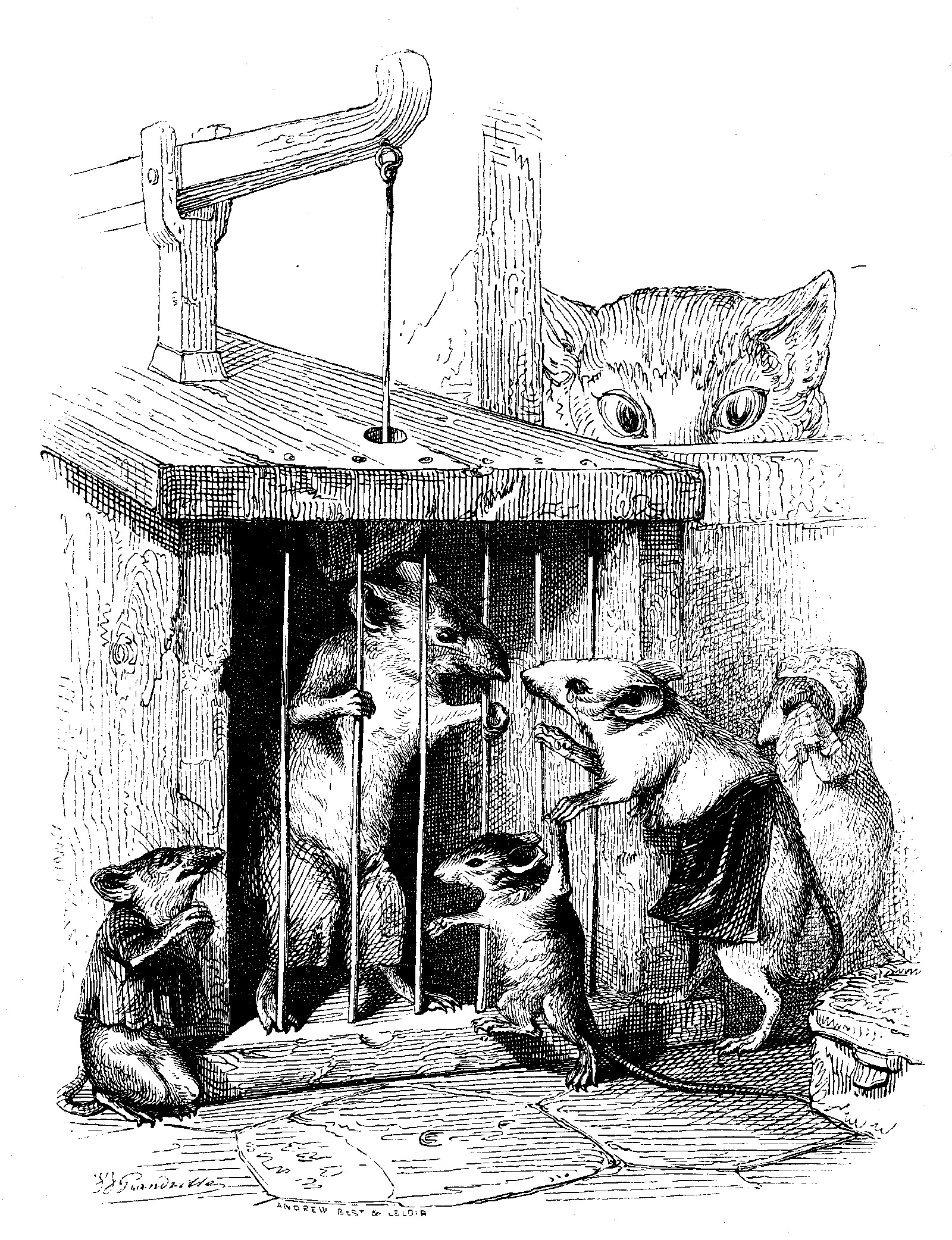

Everyone is captive in Fernando Aramburu’s novel Homeland. People yearn for freedom and independence, and find only entrapment and incarceration. It is also a novel packed with accidents and illnesses. One woman is paralyzed by a stroke. One suffers urinary incontinence. Another faces an unwanted pregnancy. Four cancers are reported, three car crashes. A boy’s face is disfigured. A beloved cat is flattened. One young man passes out from the pain of kidney stones. Another is operated on for hemorrhoids. Three people consider suicide, while a fourth does indeed shoot himself. Not surprisingly, the dominant emotion is fear; the quality most in demand is courage. To complicate it all, there is the armed struggle for Basque independence—intimidation, beatings, Molotov cocktails, murders.

Essentially, Homeland is a two-family saga, spanning the years from Franco’s death in 1975 until just a little short of the present time. The location is an unnamed Basque village near the northwest coastal town of Donostia, or San Sebastián as the Spanish call it, where Aramburu was born. Although dates are rarely given, the story opens on the day in October 2011 when ETA, the armed Basque separatist and socialist movement, declared a permanent cessation of its campaign of violence, which had claimed more than eight hundred victims over the previous forty years. The head of one of the two families, Txato (no last names are given), is among those victims; one son in the other family, Joxe Mari, is a member of ETA. The question immediately raised is: Can the end to the armed struggle lead to reconciliation in a deeply divided community and in particular between these two families who, though once on the friendliest terms, eventually became bitter enemies? In short, can the characters free themselves from the prison of past events?

There are multiple threads to the narrative. Why was Txato, who had never involved himself in politics, murdered? Who did it? How did his death, back in the 1990s, alter relations among the members of his family and between the family and the wider community? Why did the adolescent Joxe Mari join the armed struggle? And now that he has been captured and jailed for multiple murders, is there any way back for him? The novel proceeds in a challenging, radically nonchronological mosaic of 125 short chapters, each focusing on one of the nine members of the two families at different moments over thirty or more years. The style is rapid, dramatic, colloquial, shifting back and forth between third and first person often in the space of a few lines. To add to the immediacy, Aramburu uses a technique of constantly questioning what has just been stated: “Txato got to the office early. Early? Yes, just after six.” “Joxe Mari did not really trust him. Why? I don’t know.” “They learned to prepare booby traps and car bombs. What else?” “Was she expecting a visitor? Yes and no.”

The characters likewise frequently punctuate their speech and thoughts with questions: “Are you kidding?” “Me, an informer?” “What’s she trying to do? Provoke me?” As a result, the narrator’s voice mingles and fuses with theirs, sometimes leaving it unclear who is speaking. The disorientation that ensues, particularly in the opening pages as the reader struggles to come to grips with the nine unusual names and the overall trajectory of their intertwining stories, tends to reinforce the sense, which all the characters share, that life is an accident waiting to happen, or a series of accidents. Ominous, cryptic chapter headings intensify the disquiet: “Moving by Night,” “Flood,” “A Box of Flames,” “The Enemy in the House,” “A Bit of Bad Luck,” “Fright.” Given this relentlessly phobic atmosphere, the prospect of an armed struggle to achieve collective freedom is unlikely to win the reader’s sympathy; life is precarious enough as it is.

At first glance it might seem that the main characters, all Basque, define themselves in relation to ETA’s nationalist and socialist agenda. Txato, an entrepreneur running a trucking company, feels “more of a Basque than all of them put together” but resists ETA’s left-wing extremism and thinks of its members as “terrorists.” His more militant workers consider him unpatriotic when he does not support a strike after an ETA leader is assassinated. Txato’s wife, Bittori, is politically neutral until her husband is first threatened, then killed, after which she is viscerally anti-ETA, locked away in angry grief.

Their son, Xabier, who becomes a doctor in a San Sebastián hospital, a worried young man constantly anxious about his mother’s welfare, follows the same pattern. As a teenager, the younger daughter, Nerea, “loved that motto on everyone’s lips, the one you could read on so many walls: Happy, Combative Youth. And, happy, combative, young, she voted for the Herri Batasuna party”—the Basque nationalists. But she is unaware that she has been pushed to study law in distant Zaragoza because her father is being intimidated by ETA after refusing to pay the full amount of the “donation” the organization has demanded of him; he is worried the nationalists will punish him by attacking her. Here is a typical paragraph, bringing all the family members together and shifting rapidly through time to points before and after Txato’s murder:

Advertisement

Now that Nerea was in Zaragoza, Txato thinks the fear doesn’t weigh down on him as much. We’ll never know. That man, Bittori said, was buried in a shroud of secrets. It’s true that he looked less anguished after his daughter left to study far away. And Xabier? Well, since he wasn’t living in the village, Txato thought he was out of danger.

Exchanges within the family are made tense by an aggressive concern that others are not taking sufficient precautions, or alternatively are giving way too easily to the demands of the men of violence. Despite their evident unity as a family, they are in a constant state of irritation and conflict.

The other family is headed by Joxian, Txato’s old cycling partner and a friend he would have liked, “if he’d been brighter,” to join him in his company. In the event, Joxian “hesitated, lacked spirit,” and as a result has “a crap salary” in an iron foundry, where he submits to ETA pressure of every kind. Unable to stand up to his feisty wife, Miren, or indeed to anyone, he takes refuge in cycling, drinking, and gardening and is rarely present to offer guidance to his three children. When ETA begins a smear campaign to isolate Txato, Joxian reluctantly cuts off all relations with his friend, though without any enthusiasm for the cause.

Just as the husbands were once best buddies, so, following the book’s unapologetic schematism, were the wives:

Did they get along? Very well. They were intimate. One Saturday the two of them were going to a café on the Avenida, the next Saturday to a churrería in the Parte Vieja. Always to San Sebastián. They called it both San Sebastián and Donostia, its Basque name. They weren’t strict. San Sebastián? Okay, San Sebastián. Donostia? Okay, Donostia. They would start speaking in Basque, switch to Spanish, go back to Basque, that way all afternoon.

But while Bittori respects Txato, Miren has nothing but contempt for Joxian, if only because, by earning so little, he condemns her to being constantly worried about money. Her elder son, Joxe Mari, on the other hand—“a healthy, robust boy hungry as a bear”—is attractive for his youthful manliness, his sporting prowess, his obvious courage. Initially, Miren despairs of his growing interest in the armed struggle. “He’s become a thug,” she complains to Bittori, who reflects that the family was “not even remotely” nationalist. However, once the “rascal” has been “slipped the poisonous doctrine” and is on the run from the police, his mother is converted into a passionate ETA supporter. It’s the beginning of the end of her relationship with Bittori.

The oldest child, Arantxa, is “a really pretty girl—according to her mother, the prettiest in town. With that face and those eyes and that mane of hair she was destined for flirtation.” But she falls out with her mother when she flirts with then marries a boy who doesn’t speak Basque. It’s a betrayal of their community. Joxe Mari is disgusted.

Arantxa forms an alliance with her younger brother, Gorka, giving him books to read and encouraging him to stand up to the bullying Joxe Mari. The more sensitive, intellectual Gorka soon “outmatched Joxe Mari in his use of Basque. He regularly read literary works by euskaldun [Basque] writers and since the age of sixteen wrote poems in Basque.” In opposition to his mother, Joxe Mari, and the feverish atmosphere of the nationalist struggle, Gorka buries himself in books, eventually winning the respect of the nationalists by writing and publishing in Basque. This appears to align him with the author’s views of what constitutes admirable and admirably safe behavior.

This family too is constantly arguing. The gift of a cake from a man whose van has hit the young Gorka, causing him to break his nose, becomes the source of violent family argument when it appears someone has stolen a first slice during the night. Gorka’s attempts to conciliate “only enraged the family more.” To the extent that the emotional tone of the two families differs at all, it is in the vehemence of their conflicts. Quarrels in Txato’s family are sultry and repressed; in Joxian’s, or perhaps we should say Miren’s, they are wild, rash, explosive.

Advertisement

Gradually, one appreciates that the characters are not to be understood in relation to the Basque cause but as expressions of fear and courage, caution and recklessness, weakness and strength, submission and independence. Nerea, for example, is strong and independent only insofar as she lives in denial of the real situation around her. When her father is killed, she refuses to return home for the funeral and insists that a young man make love to her that very night. But confronted with a corpse in a car accident, she breaks down. Her brother, Xabier, is fearful and cautious in the extreme, turning down a bold sexual advance from Arantxa in adolescence (“I’m soaking wet,” she begs him) because the families are so close that he fears the relationship would be incestuous; he will attach his whole identity to the sadness surrounding his father’s murder, to the point of being afraid of experiencing happiness.

In the other family, Gorka, fearing he will be caught up in the nationalist struggle, develops his own “Personal Liberation Movement, the objective of which was limited to a single point: achieve independence.” Discovering his homosexuality, he is careful not to declare it openly for many years. As a writer, he publishes children’s books, since to write for adults would be dangerous.

Those who show great courage are attractive but end badly. Txato is proud of his father for having stood up to Franco, and determined himself to stand up to ETA—“They’re going to learn who Txato is”—but hardly diplomatic, hardly wise. “You’d be alive today if you weren’t so hardheaded,” his wife reflects. Joxe Mari is a reckless, dangerous spirit, but not essentially evil. The real monster, Aramburu seems to suggest, is the community that demands submission from the individual. Far from an organization fighting for liberty, ETA is coercive and imprisoning. It destroys the impetuous Joxe Mari and his feckless companions, all dead or jailed, as surely as it uses them to wipe out people like Txato. The Catholic Church is shown as complicit; the local priest, Don Serapio, reeking of bad breath, encourages the religious Miren to think of her older son as a hero and of the people’s cause as sacred (“If our language disappears…who will pray to God in Basque?”), and he discourages the widowed Bittori from returning to the village because her presence is divisive. A community united in a cause and a faith is a community whose every member can be manipulated and controlled.

The figure of Arantxa becomes emblematic. Headstrong by nature, she enjoys a lively adolescence with the boys. She feigns illness to resist being drawn into an ETA protest march. She flies to London for an abortion—illegal in Spain at the time—hiding it from her parents and priggish brother Joxe Mari, who, for all his bullying and patriotism, has never had sex, since his ultra-Catholic, nationalist girlfriend won’t hear of it. The man Arantxa marries turns out to be a tangle of money worries and angry phobias, constantly warning their two children of “an atrocious panorama of privations” and always ready to say “something negative, ill-omened, sorrowful.” She stops seeing her mother for five years after ETA blows up a friend of theirs. Unhappy with her husband, she is trapped by economic circumstance, but eventually abandons him and returns to her parents, only to suffer a stroke and consequently “locked-in syndrome”—near-total paralysis. As the novel opens, she is a pathetic figure who has just learned to communicate by writing with one finger on an iPad. Yet this extreme form of entrapment, an evident physical correlative of the community’s shared psychological condition, frees her to be completely courageous and independent. In the long quest for reconciliation between the families, she will be the supreme facilitator, welcoming Bittori back into the village, reconnecting with Xabier and Nerea, even encouraging Joxe Mari to consider asking Bittori for forgiveness.

Homeland is a dense and deftly plotted story, full of suspense as it circles toward the moment when Txato is murdered or as it follows the lives of Joxe Mari and his ETA companions on the run, rich with detail as it conveys the lives and habits of its characters and their different reactions to tragedy, always sensitive to the profound changes of mood and mores that eventually lead to the cessation of the armed struggle. Nevertheless, over 580 pages the novel’s mannered stratagems and general air of didactic contrivance are wearying, its closing reconciliations unconvincing. Seeking to bring present and past together, Aramburu repeatedly gives us Bittori going to the cemetery to converse at length with her dead husband (“Our daughter is in London by now…[though] she hasn’t bothered to call me. Did she call you?”), or Miren in church beseeching and scolding the local patron saint, Ignatius of Loyola (“Whose side are you on, with them or with us?”). Both Arantxa and Joxe Mari speak at great length with mirrors, seeking to recover the past.

Minor characters neatly complete the range of positions in the fear–courage, dependence–independence spectra. Nerea marries a man who insists on total freedom, convincing her that it’s OK for him to have as many girlfriends as he chooses, but who also shows spectacular courage when he chases a thief who has grabbed her bag in Prague, leaping into the waters of the Vltava to recover it when the thief tosses it away. In jail Joxe Mari, having arranged a “conjugal visit” with a girl who has been writing admiring letters to him, finally discovers sex, and “for the first time…had the physical sensation that he’d wasted his youth.” Gorka lives with a partner, Ramuntxo, whose abject fear of his ex-wife and demanding young daughter is the stuff of farce. The feelings of warmth when reforms to the law allow the gay couple to marry and Gorka’s parents, Joxian and Miren, unexpectedly turn up at the wedding, apparently entirely at ease with this development, are welcome but strain the reader’s credulity.

In general, Aramburu’s manipulation of his village folk, his frequent use of such expressions as “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph” or “The guy with the big balls,” or the many, many words in Basque create a rather old-world, even patronizing tone. Sometimes it seems that, rather than local circumstances, it is the author who is imprisoning the characters, obliging them to behave blindly at first, then with great enlightenment, exactly as suits the book’s development. The impression is not helped by Alfred MacAdam’s translation, which veers wildly between seeking idiomatic intensity in an American vernacular (“holy shit,” “son of a bitch,” “motherfucker,” “lowdown, dirty trick”) to a slavish tracking of Spanish syntax (“She instantly understood that what happened…was true and that not even it was the worst thing”; “When he removed [the mailbox] a square appeared the color the walls were painted long ago, when Nerea had yet to be born, nor had Miren’s son, that criminal”). With page after page of this, all distinction between the way the various characters think and speak is blurred, clunky, and quaint, as if they were migrants who had learned a few English phrases but were otherwise struggling to express themselves.

Toward the end of the novel, downing a double cognac “to gather courage,” Xabier attends a meeting for the victims of terrorism at which a writer presents a book that aims, he says, “to paint a representative panorama of a society subjected to terror,” by asking such “concrete questions” as “How does a person live intimately the disaster of having lost a father, a husband, a brother in an attack? How does a widow, an orphan, a person who’s been mutilated face life after a crime?” This blatant authorial intervention makes clear, if readers were still in doubt, what Aramburu thinks of ETA: “a handful of armed people, with the shameful support of one sector of society, [deciding] who belongs to [the] homeland and who should either leave it or die.”

But while few would hesitate to condemn ETA’s strategy of terror, it is curious that nothing is said about the issue of a community losing control of its “homeland” or seeing it subsumed in a larger dominant culture. The Basque country, mostly in Spain but partly in France, has around 2.5 million inhabitants, about half of whom speak Basque, a language whose use was banned under Franco. A survey in 2004 suggested that as many as 33 percent of Basques favored independence and 31 percent a federal relationship with Spain. Although these figures have fallen sharply since then, after the region began receiving generous subsidies from Madrid, it seems odd that in Aramburu’s novel none of the more attractive characters expresses any sympathy for the Basque situation. The only educated person who articulates the motives for an independence struggle of whatever kind is the “unctuous” septuagenarian Don Serapio, whose ideas we are invited to put on the same level as his halitosis.

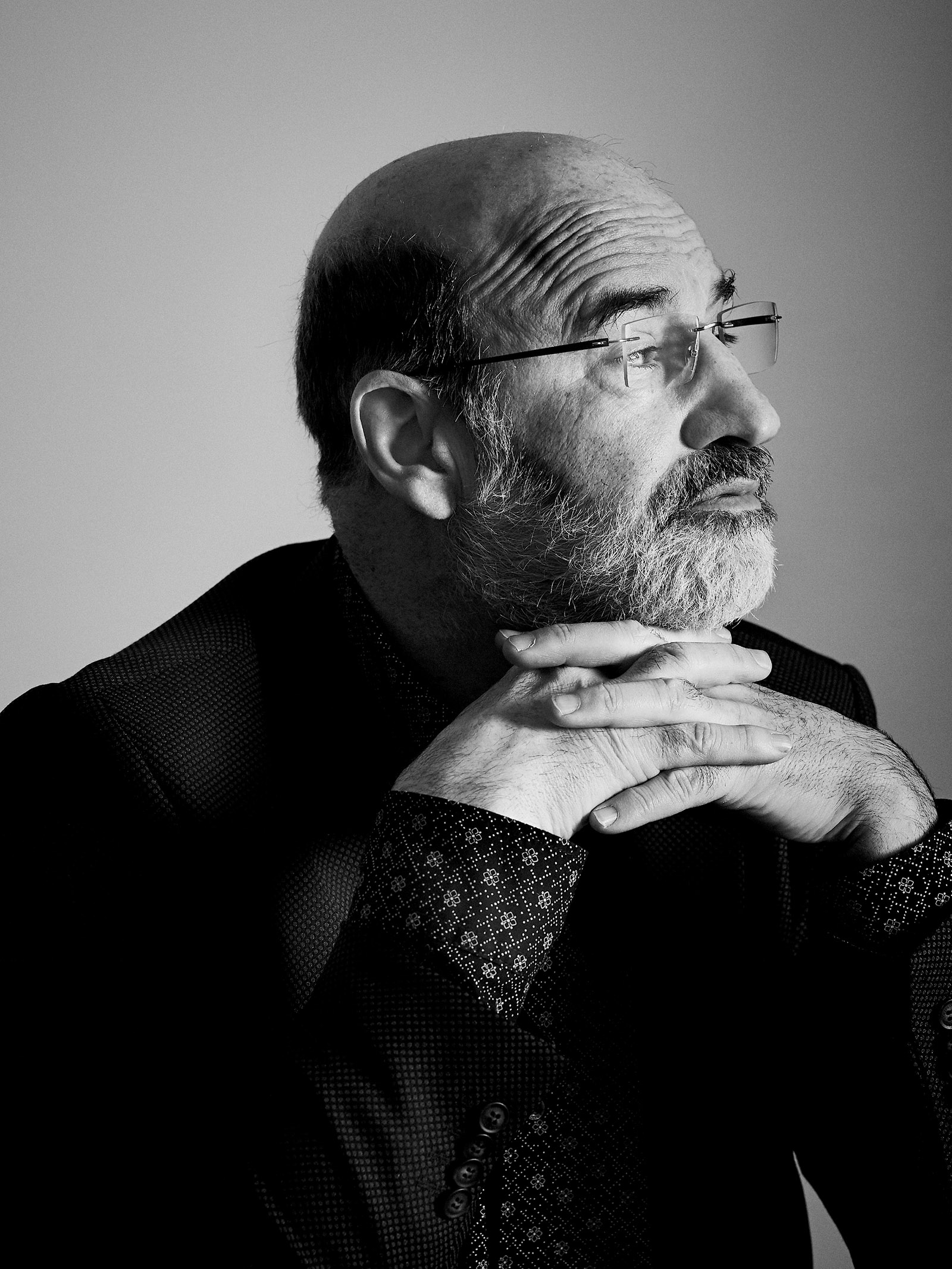

Born in San Sebastián in 1959, Aramburu studied in Zaragoza and left Spain for Germany in 1985 to teach Spanish there. Perhaps this absence explains why his book so frequently presents itself as an effort of memory. The writer Ramón Saizarbitoria, who is some fifteen years older than Aramburu, has been a constant presence in San Sebastián, and his long novel Martutene, written in Basque and published in 2012, likewise treats the state of Basque culture in the aftermath of the armed struggle.* A more difficult, less marketable novel than the dramatic Homeland, Saizarbitoria’s book gives the non-Basque reader a sense of the profound emotional disorientation and unease that gather around the question of belonging in such an embattled community. In particular, one of the central characters, Julia, a translator, is the widow of an ETA fighter who faces the problem of how to talk about the dead man to their son Zigor, a boy christened with his father’s nom de guerre: Is he to be thought of as a warrior, a martyr, or a terrorist? Julia “wanted the violence to stop before Basque patriotism was completely ruined by it…before Basque society became a sad case of collective cowardice.” All the same, “having to deny dreams and feelings that she thought beautiful, that were part of her character, just because they once fed some people’s madness hurts her.”

Toward the end of Homeland, on the contrary, it simply seems there is no Basque problem at all, and very likely never was. The entire struggle was an ugly error, promoted only by the evil and the ingenuous, aligned with bigotry and superstition. The individual must simply emancipate him- or herself and enjoy the freedoms of a rapidly globalizing world. Perhaps in the original Spanish, for readers who are more aware of the events Aramburu talks about and who experience his style differently, this is not the case. In this English edition, however, it appears that any politics based on communal identity can be dismissed as anachronistic, a stance emphatically belied by the many independence movements challenging the European status quo from Scotland in the north to Catalonia in the south, not to mention a general assertion of national identity across the continent in opposition to the amorphous and beleaguered European Union. It would seem unwise not to take these sentiments seriously.

-

*

See my review in these pages, June 8, 2017. ↩