Many years later, as I faced the deadline for writing this review, I was to remember that distant afternoon when Gabriel García Márquez showed me the Spanish manuscript of Chronicle of a Death Foretold and then gently refused to let me read the novel until its forthcoming publication.

We were spending a week together in August 1981 at the Mexican resort of Cocoyoc, along with eight other jurors awarding a literary prize for the best book on militarism in Latin America,1 and Gabo (as everyone called him) was bubbling with enthusiasm at having completed what he considered his masterpiece. “I can’t let you even have a peek,” he said to me with a smile both impish and contrite, “because I’d get into trouble with the two women who rule my life: Mercedes and Carmen.” He was referring, respectively, to his wife and his agent, whose authority over him was well known. “I was brought up,” he added, “in a household full of strong, decisive, intelligent women and learned early on to respect them more than anything in this world or the next one.”

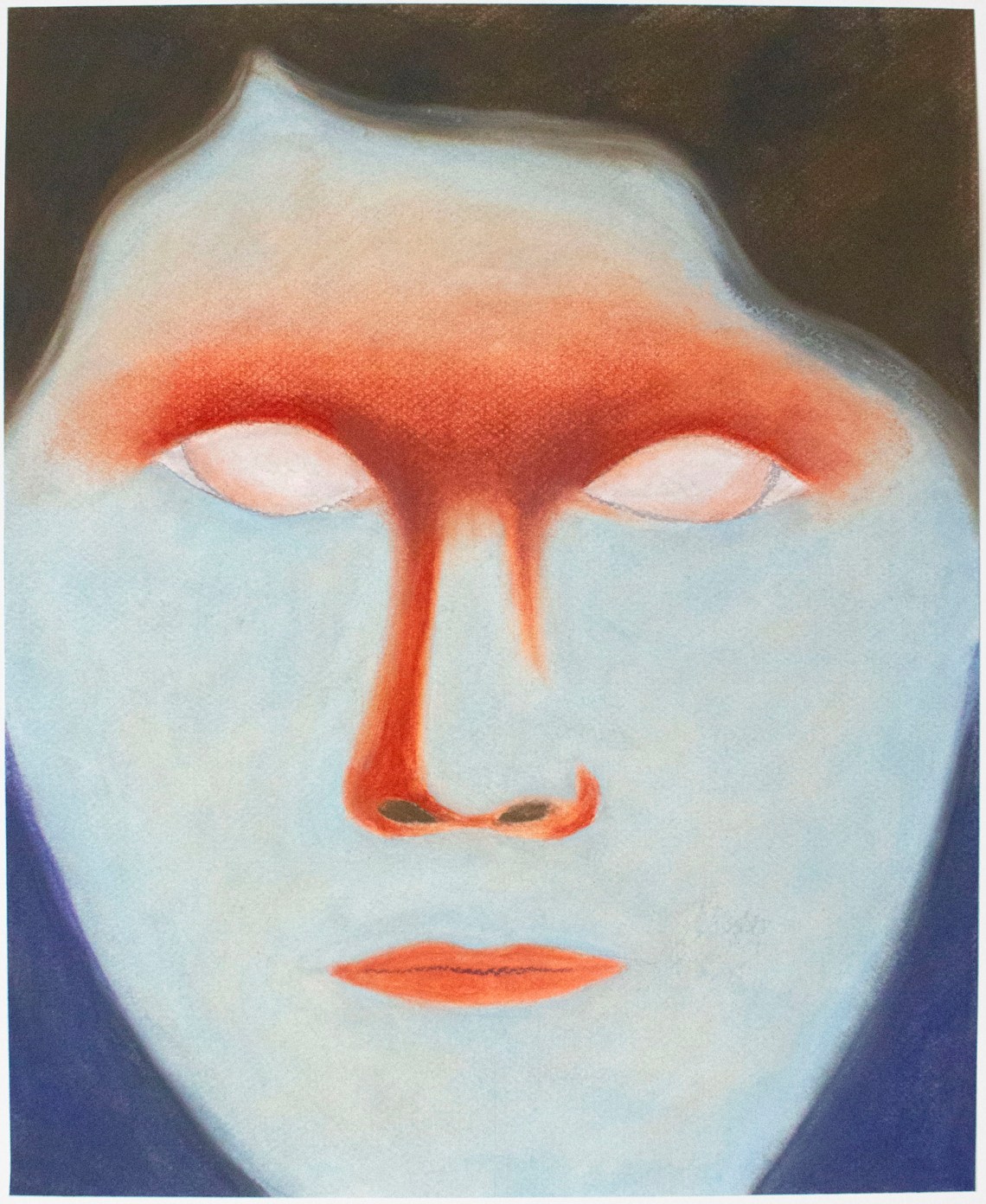

I was not surprised, as he had frequently expressed similar sentiments. What seems noteworthy today, as one reads his posthumous novel Until August, is that despite his reiterated reverence for the female sex, he never—until now, that is—published a long work of fiction in which a woman was the uncontested protagonist.

Exceptional, fully developed female characters abound in his work: the multifarious mothers and grandmothers, sisters and daughters and lovers of the Buendía family in One Hundred Years of Solitude, as well as scores of others in book after book. And yet, endowed though their mostly tragic lives may be with dignity and agency, they live in a world forged by machos, basically patriarchs, large or small, who determine priorities through their stubborn search for power or their unrelenting lust. The women are there to fix the messes these men leave behind and to service their male nostalgia and desires.

This is the world from which the protagonist of Until August, forty-six-year-old Ana Magdalena Bach, strives to escape. For the last eight years she has been visiting the tomb of her mother, Micaela, on an island off the Caribbean coast of Colombia. On each sweltering August 16, the anniversary of her death, Ana Magdalena has cleaned the grave, laid gladioli on it, told Micaela the latest news, and then returned to the husband on the mainland to whom she has been contentedly married for twenty-seven years. But on the occasion that opens the novel, she engages in a one-night stand with a stranger of consummate sexual prowess whose name she never finds out. That first isolated act of adultery takes place almost reluctantly, as if it were someone else’s erotic adventure, but subsequent trysts in the following years, always with a different man, open her to the realization of what has been missing in her middle-aged life, as she grows closer to death with each wearisome second that ticks by.

García Márquez deftly registers the fluctuations of Ana Magdalena’s joys, reservations, and disappointments on this journey of self-discovery. After that first encounter, her sense of satisfaction with what initially seemed a transitory lapse is undermined once she awakens. To her horror, the departed lover has left a twenty-dollar bill between the pages of a book she was reading (appropriately, Bram Stoker’s Dracula). Rather than the bodice-ripping sex, it is this act of turning her into a prostitute that becomes the defining moment of her odyssey. It troubles her identity as the free woman she believes herself to be, breaks down the romantic illusion with which she embarked on this illicit rendezvous, and she spends the rest of the novel trying to efface that gesture of subjection.

Ana Magdalena returns home oddly changed, looking at her former life with “chastened eyes.” But she will need an ongoing crisis with her clueless but quite wonderful husband, and several more visits to the island and nights of both successful and frustrated love with anonymous gentlemen, to figure out where this rebellion against conventional marriage is leading her.

From the very first words that describe her aboard the ferry that takes her to the island, Ana Magdalena comes across as strikingly different from many of the other female characters that populate García Márquez’s fiction. Some of them are bursting with sensual fertility and joy, others stew in the lonely swamp of their bitterness, but almost all are defined by their lack of an education, whereas Ana Magdalena belongs to a cultured and privileged upper-middle-class elite. The second of her carnal unions occurs in a luxury Carlton hotel, one of the “towering cliffs of glass” that she witnessed going up “every year while the village grew more and more impoverished.” Besides a bar, a cabaret, and a solicitous staff, there is, notably, ice-cold air-conditioning in her suite on the eighteenth floor.

Advertisement

That artificial air establishes how remote her world is from those of García Márquez’s previous novels. The famous opening line of his most famous work, One Hundred Year of Solitude (“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice”), implies a premodern country where ice is a marvel. It is that past full of prodigies that García Márquez riotously mined all his literary life, without ever writing a novel set in his own time. With Until August he dared to. In the late twentieth century, on a planet where flying machines perform the hourly miracle of defying gravity, there is no room for levitating priests or damsels who ascend to heaven as a sign of their purity. What besieges Ana Magdalena is the crushing reality of the mundane from which there seems to be no escape, even if, when she returns home from her first adventure, she has the momentary impression that nature itself has responded to her earth-shattering infidelity:

In a panic she asked Filomena, their lifelong housekeeper, what disaster had occurred in her absence to keep the birds from singing in their cages and why her planters of flowers from the Amazon, hanging baskets of ferns, and garlands of blue vines had disappeared from the inside courtyard.

In any of García Márquez’s previous novels, this would be the chance for a supernatural and mysterious response from the earth and the air to the alteration in someone’s existence. Here the explanation is rational and ordinary. She had given instructions for the plants to be taken to the patio to enjoy the rain: “It would take several days before Ana Magdalena became aware that the changes were not to the world but to herself.” She is the vast, enigmatic territory that she must confusedly explore if she is to emerge from her own labyrinth of solitude.

But there is still a place for magic, even in a disenchanted world. In the last chapter the words “magic” and “magician” are slipped in repeatedly, hinting that something extraordinary is about to happen. This moment of transfiguration happens in a cemetery, a location that has been central to García Márquez’s literature from the very start. His first novel, Leaf Storm (1955), is a Faulknerian retelling of Antigone. A colonel in Macondo is determined to bury the corpse of a doctor who, because he refused to treat those wounded in Colombia’s civil strife, has been left to rot in his house. Macondo begins as a paradise in One Hundred Years of Solitude, until one by one all its inhabitants are dead and the town itself becomes a vast graveyard, mirroring the “windstorm of fatality” that García Márquez experienced when he returned as a young adult to Aracataca, the town where he was born and grew up until the age of eight.2 More and more funerals pile up in The Autumn of the Patriarch, The General in His Labyrinth, and Love in the Time of Cholera.

It is apt, then, that his posthumous novel should climax in a graveyard. When Ana Magdalena visits her mother’s tomb for the last time, it is covered with flowers, brought, the caretaker informs her, several times a year by an elderly gentleman who he presumed was a family member. It is a “blazing revelation”: her mother had a lover! That is why Micaela would travel to the island during her last years, why she insisted on being buried there. Though shaken by the news, Ana Magdalena does not feel sad “but rather encouraged by the realization that the miracle of her life was to have continued that of her dead mother.” She awaits a sign that her mother is blessing her from the grave, but none comes. That night, having rejected another possible lover, she “cried herself to sleep furious with herself for the misfortune of being a woman in a man’s world.”3

But it is not in frustration that the book ends. The next morning Ana Magdalena decides to exhume her mother’s body. And now the sign she was awaiting does indeed arrive. She sees herself “in the open casket as if she were looking in a full-length mirror,” but she also feels seen by her mother “from death, loved and wept for.” It is a double encounter—with her future dead self and with her mother still somehow alive—that allows her to say “goodbye forever to her one-night strangers and to the hours and hours of uncertainties that remained of herself scattered around the island.” Carrying the sack of bones, Ana Magdalena returns to the mainland and her loving husband. It is not clear what she will do next, only that her midlife crisis is over, thanks to the intercession not of another man but of another woman, whose remains will now accompany her until the day she herself dies.

Advertisement

García Márquez once told me—at least this is how I remember the conversation4—about entire villages in Colombia that hauled their cemeteries with them as they migrated, trying to keep some semblance of the past alive in the midst of the multiple catastrophes that had uprooted them. Those bones were a way to provide stability in a landscape where everything had become unfamiliar. When Ana Magdalena does something similar with what is left of her mother’s corpse, she is enacting the same sort of ritual as those villagers (and other García Márquez characters5), finding an anchor that reminds readers that our ancestors have much to teach us if we could only learn how to listen to them.

However, though this closing image of a woman who has lost her way and been reconciled with life through her dead mother is emotionally gratifying, the last lines of the novel feel truncated and anticlimactic. Anticipating her husband’s horror at the sack of bones she is bringing home, Ana Magdalena tells him not to be afraid, that her mother understands: “She’s the only one who could. What’s more, I think she’d already understood when she decided to be buried on that island.”

These sentences that present Micaela as a kind of oracle who has forecast her daughter’s destiny are reminiscent of many of García Márquez’s most felicitous intuitions. But compared with any of the brilliant endings for which he is known, they seem inconclusive and awkwardly phrased. In No One Writes to the Colonel (1968), for instance, the impoverished colonel, who has been waiting for decades for his veteran’s pension, informs his wife that he won’t sell the rooster that might win a cockfight forty-four days hence and help them survive. When his wife insists that the rooster might lose and asks meanwhile what they will eat, his answer is memorable:

It had taken the colonel seventy-five years—the seventy-five years of his life, minute by minute—to reach this moment. He felt pure, explicit, invincible at the moment when he replied: “Shit.”6

Almost fifty years later, on July 5, 2004, already battling memory loss, García Márquez gave tentative approval to a definitive version of Until August. Tentative, because he added, “Grand final OK. Info about her CH 2. NB: probably Final ch / Is it the best?” My guess is that he had in mind those other sublime endings and was concerned that perhaps the last words he had ascribed to his female protagonist did not afford her the consummation she deserved.

One can theorize, of course, that this indecisive ending was what he had planned: to purposefully preclude an unforgettable sentence or a totalizing gesture as the character said farewell, thus sidestepping his often expressed aspiration that each of his works be a “total” novel. In his only novel to focus exclusively on a female figure, was he possibly grasping for the ambiguous endings of Virgina Woolf, an author he venerated? And yet there are those prescient words—“Is it the best?”—as well as several inconsistencies and redundancies in the text, all of which imply distress at publicly producing anything that did not meet his exacting standards. That lingering doubt certainly gnawed at him, because his last instructions to his sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo, about what to do with Until August were: “This book doesn’t work. It must be destroyed.”

For many years it rested among his papers in the vaults of the University of Texas, Austin, exclusively available to visiting scholars, and was not rescued from obscurity until his heirs belatedly decided to publish it posthumously. They argued not only that they found wonders in the book but that when their father had ordered its destruction, his faculties had diminished to the point that he could not appreciate its merits.

When I heard that one surviving literary work by García Márquez was to be offered to his readers, what came almost immediately to mind was the first short story he published, when he was barely twenty, written the night after he read Kafka’s Metamorphosis. “The Third Resignation” (1947) features a character who, though dead, is able to observe what happens to his body as it decays over the course of several decades. At first he is delighted to find himself left alone with his solitude, his senses intact, but toward the end “his limbs would not respond to his call. He could not express himself and that…struck terror in him; the greatest terror of his life and of his death. That he would be buried alive.”

I like to speculate that the youthful García Márquez was visited, while writing that story back in 1947, by a premonition (he who adored forewarnings and cycles and repetitions) about what might someday happen to his own future self: he might find himself in a position akin to being buried alive, unable to express his innermost feeling.

Did his sons, then, make a mistake by going against their father’s wishes, by deciding what are to be the final words of his to see the light of day, remnants with which he was not fully satisfied? Predictably, the appearance of Until August has stirred a considerable amount of controversy, with many arguing that it is a disservice to allow such an unfinished minor work to circulate.

At the end of their preface to the novel, his sons justify this betrayal (they agree that the book is incomplete) by declaring that they have “decided to put his readers’ pleasure ahead of all other considerations. If they are delighted, it’s possible Gabo might forgive us.” I found this plea for forgiveness poignant, albeit simultaneously a way of shifting onto readers the responsibility for the book’s publication. Even in the unlikely case that every reader were delighted, the question still remains of how García Márquez (the writer and not the loving father) would have reacted to the appearance of this posthumous novel, whether—or not—it completes his trajectory as a writer.

Unique though Ana Magdalena is to the canon of García Márquez, he had often narrated the plight of female characters from their perspective, if not in novels then in a number of accomplished short stories that span his literary career. In “The Woman Who Came at Six O’Clock” (1950), a prostitute convinces the restaurant owner José to provide an alibi for a murder she may have committed. In “Tuesday Siesta” (1962), a mother brings flowers to the grave of her thieving dead son, defying a hostile and possibly murderous town. In “The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother” (1972), the twelve-year-old Eréndira, inadvertently responsible for a fire that annihilates all her grandmother’s possessions, is prostituted in perpetuity by the old woman to pay for the damage. And in “Maria dos Prazeres” (1979), an aging whore preparing for death in Barcelona finds love with an adolescent boy. Although it must have been tempting, García Márquez rightly declined to extend each of these tales into a novel. Their heroines fit flawlessly in their circumscribed universe.

This was how Ana Magdalena Bach was born. She initially appeared in two short stories, one of them published in 1999 in the Colombian journal Cambio (and later in translation in The New Yorker) and the other read that same year by the author at the Casa de América in Madrid, which would evolve into the first and third chapters of Until August. What was so fascinating about this particular woman at this particular moment in the life of the aging writer that he felt compelled to stretch these two chapters into a lengthier work? What made her a character who, like Clarissa Dalloway, “clamored for more life”?7

García Márquez zealously projected onto his final protagonist some of his most intimate tastes. Her name comes from the second wife of his most beloved composer, whose cello sonata he once said he would take to a desert island if he had but one choice. Indeed, she is surrounded by men in her family (father, husband, son) who are dedicated to classical music, and Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Copland, and Bartók are played at some point during the novel. But like her creator, she is also entranced by songs and dances (boleros, danzones, waltzes, salsa, jazz) that provide the right atmosphere for courtship and the torrid couplings that will eventually take place. This mix of high and low culture mirrors García Márquez’s embrace of a dual heritage that allowed him to appeal to both postmodern sensibilities and a popular audience, bridging the divide that has bedeviled Latin American literature from its origins.8

In fact, literary hints are strewn throughout the novel. The title is an homage to Light in August by William Faulkner, the author who most influenced him. Ana Magdalena, a high school teacher who is only a couple of courses away from graduating with a degree in literature, assiduously reads the writers who are García Márquez’s favorites: Camus, Hemingway, Defoe, Bradbury, Greene, Borges (and Stoker). And it is no coincidence that Micaela, the dead mother who helps her daughter read reality in a different way, was “a famous Montessori teacher,” because it was just such a teacher in a Montessori school, Rosa Elena Ferguson, who taught the young Gabito to read and instilled in him a love for poetry and the Spanish language that would be central to his vocation, and who was even, it has been said, his first love.

But although Until August is a remarkable book, it does not find its author at the peak of his abilities. It is praiseworthy but not the masterpiece it could have become if he had not been ailing and could have afforded his female alter ego the sort of treatment Anna Karenina or Madame Bovary received. And yet, maybe it did befall him after all at exactly the right time, when he had published what were thought to be his last two novels. Both of them feature young girls who cast a spell over much older men. In Of Love and Other Demons (1994), thirteen-year-old Sierva María besots the thirty-six-year-old priest Cayetano Delaura, tasked with exorcising the demons presumably inside her body. And in Memories of My Melancholy Whores (2004), it is a fourteen-year-old virgin whom the unnamed narrator decides to bed to celebrate his ninetieth birthday but ends up falling in love with—platonically, to my relief.

Such a fixation in an aging writer had significant roots in his early life, as he first met his future wife, Mercedes, when she was nine and he was fourteen and resolutely determined to marry her, a situation that was transferred to Colonel Aureliano Buendía and nine-year-old Remedios Moscote and reappears in other works. This is not the place to delve into the deeper Latin American motives, personal and social, behind such a perverse male quest for innocence and purification through the bodies of prepubescent girls,9 but it is evident that one of Ana Magdalena’s attractions must have been how far she is from both of the juvenile female protagonists of the preceding novels. I conjecture that García Márquez was glad to be celebrating not the sort of girl he had been infatuated with sixty years earlier but the sort of mature woman with whom he had spent his adulthood and whom he so admired. He was a lifelong denouncer of patriarchy, blaming machismo and the oppression of women for the violence and misdevelopment of Latin America.10 How liberating, then, to give that budding female character the chance to blossom fully—with all her dreams, disconcerting desires, and transgressive sexuality—in a novel where she discerns the freedom that so few of his characters attain.

It is heartening that even as his memory began to fade, García Márquez risked setting out for new horizons. I can only hope that he would not have wanted his sons to condemn Ana Magdalena Bach to the flames of oblivion no matter how imperfectly she might have been wrought. Surely he would have been dismayed at becoming, from beyond death, an accomplice to the erasure of that struggle of hers to defeat that very death. Let me say, then, to Gabo’s sons: very few old friends of your father are still alive, so I’ll take it upon myself to commend you for having betrayed his last wishes and bequeathed to readers one more memorable woman, this enchanting homage to freedom.

-

1

See my “My Memories of Gabriel García Márquez,” The Nation, May 26, 2014. ↩

-

2

See the hallucinatory first chapter of his autobiography, Living to Tell the Tale (Knopf, 2003), and Alma Guillermoprieto, “Ghosts of Aracataca,” The New York Review, November 2, 2023. ↩

-

3

My translation. The translator of Until August, Anne McLean, whose renderings of Javier Cercas and Juan Gabriel Vásquez I have found unimpeachable, makes a mistake here: the Spanish desgracia means “misfortune,” not “disgrace.” ↩

-

4

See my “The Wandering Bigamists of Language,” Other Septembers, Many Americas: Selected Provocations, 1980–2004 (Seven Stories, 2004). ↩

-

5

For instance, the eleven-year-old orphan Rebeca, from One Hundred Years of Solitude, who arrives at the Buendía household carrying a bag of her parents’ bones and who will only manage to find peace years later when they are finally buried. ↩

-

6

For a further interpretation of this incident, see my review, “La vorágine de los fantasmas,” Ercilla 1.617 (June 1, 1966), p. 34. ↩

-

7

The phrase comes from Merve Emre’s insights into how Mrs. Dalloway evolved from fragments and a short story into Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece. See her The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway (Liveright, 2021). ↩

-

8

For an elaboration of this divide see my “Someone Writes to the Future: Meditations on Hope and Violence in García Márquez,” Some Write to the Future: Essays on Contemporary Latin American Fiction (Duke University Press, 1991). ↩

-

9

There is a judicious analysis in Gerald Martin’s indispensable biography, Gabriel García Márquez: A Life (Knopf, 2009), pp. 530–532. ↩

-

10

Perhaps his pithiest definition of machismo was in a conversation with Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza: “Machismo in men and in women is merely the usurpation of other people’s rights.” Gabriel García Márquez: The Last Interview and Other Conversations, edited by David Streitfeld (Melville House, 2015), p. 38. ↩