The job of the biographer who sets out to write about a great artist lies in part in resolving the tug-of-war between the life and the work. The two are intimately connected, but a body of work is never fully explained by the experiences, psychology, love affairs, or cultural setting of the person who created it.

As a result, the biographies of choreographers and dancers, like those of any other artist, tend to favor either the person or the creation. Jennifer Homans’s account of George Balanchine, Mr. B (2022), delves far deeper into his emotional life and romantic proclivities than any had before, creating a very different backdrop for the ballets than, say, the classic Bernard Taper biography. Amanda Vaill’s biography of Jerome Robbins, Somewhere (2006), offered a more vivid portrayal of his demons and insecurities than did Deborah Jowitt’s Jerome Robbins: His Life, His Theater, His Dance (2004), which tilted its attention toward the creative process and the dances themselves.

Jowitt’s approach in her new book, Errand into the Maze: The Life and Works of Martha Graham, is similar to the one she took in her Robbins biography. For her, it’s all about the dances; she comes to her subject through her long experience as a critic. After starting out as a dancer and choreographer in the 1950s, Jowitt was the principal dance critic for The Village Voice from 1967 to 2011. She has published several books of criticism, including The Dance in Mind (1985) and Time and the Dancing Image (1988).

So it is no surprise that Errand into the Maze—perhaps Jowitt’s last book, published just a week before her ninetieth birthday—is both thorough and conscientious. The dances are meticulously described, their sources and themes closely analyzed. Graham’s biography, too, is explored in careful detail. But around Graham’s turbulent love life and the emphatic importance she ascribed to sex, sexual pleasure, and her relationships with men, Jowitt exhibits a certain reticence. It is a noble approach, but one sometimes at odds with the fervid content of the dances. The dramas Graham lived out onstage were her own. As she wrote in her memoir, Blood Memory (1991):

Whether it was a dance of consuming jealousy, I Medea and he Jason, or one of tender love like Appalachian Spring, he the Husbandman, I the Bride, it came so close to real life that at times it made me ill.

(The “he” she was referring to was her partner and, briefly, husband, Erick Hawkins.)

Jowitt’s book is the latest entry in a looming tower of Graham literature that includes Neil Baldwin’s lively and engaging but oddly truncated Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern (2022); Mark Franko’s political and psychological analysis Martha Graham in Love and War: The Life in the Work (2012); Graham’s own memoir; Don McDonagh’s rather dry Martha Graham: A Biography (1974); and various accounts by Graham dancers from different periods, some collected in Goddess: Martha Graham’s Dancers Remember (1997).

The fullest and most spirited portrait of Martha Graham as a woman and an artist is still Martha (1992) by Agnes de Mille, a fellow choreographer and friend who kept close watch as Graham’s life and dances were unfolding, though she never studied with Graham or danced in her company. The two met in 1929, when Graham was thirty-five and de Mille twenty-four, but de Mille had seen her dance even earlier, when Graham was still a student at the school of her teacher and guru Ruth St. Denis, a forerunner of American modern dance. De Mille was certainly not impartial, and knowledgeable readers have pointed out inaccuracies in her account, but she knew Graham intimately. And she writes about her subject with a confidence and verve that are hard to match.

Graham’s name has become synonymous with American modern dance, even though she was not the first to do what she did—Isadora Duncan, Loie Fuller, Rudolf von Laban, and St. Denis paved the way for the revolutionary idea that dance should turn its back on the vocabulary and aesthetics of Western concert dance, i.e., ballet. Nor was Graham the only modern dance innovator of her generation; choreographers in the US and in Europe were creating new forms of expression through movement, including her colleagues and sometime competitors Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman, Lester Horton, and Katherine Dunham, whose choreographic language incorporated her research into Caribbean and African dance. In Germany and Eastern Europe there were others, including Mary Wigman, whose expressionist solos transformed the body into a vessel of emotion bordering on possession.

What set Graham apart from her contemporaries was her success at creating a vocabulary and a style so original, so recognizably hers, that they became embedded in the story of American modern art. As de Mille writes in Martha, she “had to spin this new technique out of her own entrails: a way of moving the arms, a way of moving the legs with the torso, a way of breathing.” It is impossible to mistake Graham dances like Appalachian Spring (1944) and the solo Lamentation (1930) for dances by anyone else, both because of the technique they are built upon—taut, muscular, coiled, and explosive—and because of their tone; even the few lighthearted works are fashioned out of strong, emphatic stuff. (So much so that it is easy to parody their air of importance and heavy-handed symbolism. Danny Kaye, for example, did a hilarious and not inaccurate spoof, “Choreography,” in the 1954 movie White Christmas.) The way she placed the female body and mind at the center of her dances, recognizing her sexual desires as an integral part of her artistic persona—decades before the sexual revolution—was one of her most striking innovations.

Advertisement

There is no pianissimo in Graham. The work’s sense of accentuation and importance, like a series of exclamation points, has helped it survive for almost one hundred years. The Martha Graham Dance Company, based in Greenwich Village, is kicking off its centenary celebrations this spring, two years early, performing works spanning her career, including Appalachian Spring and The Rite of Spring (1984). Dance schools all over the world still teach her technique, which is considered foundational vocabulary for any modern dancer. And yet her company’s performances can have an almost ritualized air: dutiful, flawlessly executed, presented as if through a microscope, but somehow lacking in the electricity that emerges from old films and accounts of performances when Graham was in her prime, in the 1930s and 1940s. “Perhaps,” as the New Yorker dance critic Arlene Croce put it in 1977, “there’s a statute of limitations on how long a work can be depended upon to force itself through the bodies of those who dance it.”

This may be especially true of Graham’s work, connected as it was to her own body and mind. “I choreographed for myself,” she writes in Blood Memory. “I never choreographed what I could not do.” What she could do was in part a function of the specifications of her body, described by Elizabeth Kendall in her book on the birth of American modern dance, Where She Danced (1979): “She was small, with a long torso, short legs, and a longish, serious face.” Graham was strong and flexible. She could kick her leg up high without effort. She could jump straight into the air without visible preparation. As Jowitt describes, she could lower herself backward to the floor in what she called a “back fall” in a single beat, bending her knees so deeply in the process that a normal person would have ended up in the emergency room. She could stand on one leg and fold it beneath her so that the rest of her body descended toward the floor as if riding an elevator, and then rise back up, without shaking or falling over. She could sit on the floor with her legs splayed in front and behind and twist and bend her torso in every direction; she could dive into a deep arabesque headfirst while turning on the other leg. She could do these things despite having begun her training in dance at the impossibly late age of twenty-two. And she was implacable when it came to molding her body and the bodies of her dancers to execute whatever perilous, difficult movements she asked of them.

The technique Graham taught in class came out of the dances she was in the process of creating. As Jowitt explains, “Her physical skills and choices were developing to suit her themes and the times she lived in.” In the late 1920s she was starting to develop the radical works that brought her to the attention of the dance world. They made the bodies of her dancers look like architectural or even geological structures—“bound up,” “iron,” “rock-hewn,” in de Mille’s words. It was during this period that she came upon an idea that would become central to her movement language and to the intense emotions it could express. “Contraction and release,” as it came to be known, isn’t about the legs or the arms but the very center of the body, what we now habitually refer to as the core—the abdominal and pelvic muscles, the diaphragm. The phrase described not just a movement but the thing that keeps us alive and reflects our state of mind: breath.

None of the handful of books about Graham I’ve read explains where the idea of contraction and release came from, probably because she destroyed as much of her writing and correspondence as she could. But it can be boiled down to a way of using the exhalation and intake of breath to create extreme contrasts in the body. Jowitt describes it like this:

Advertisement

As if socked in the solar plexus, the dancer expelled air so deeply that her body became concave, pulling deeper into itself (or she might gasp—the kind of gasp so pulled in and up that the air didn’t fill her lungs.) The inevitable intake of breath restored the body to erectness, the dancer to a waiting Apollonian calm.

And here is de Mille:

The spasm of the diaphragm, the muscles used in coughing and laughing, were used to spark gesture…. The arms and legs moved as a result of this spasm of percussive force, like a cough, much as the thong of a whip moves because of the crack of the handle. The force of the movement passes from the pelvis and diaphragm to the extremities, neck and head.

The result is movement that communicates a heightened state of emotion. It is the difference between the serenity and harmony of a Botticelli and the tension of a Schiele or a Giacometti. Graham told her students, “There is a moment between contraction and a release that must say something either of joy or of sorrow.” In other words, it’s not neutral, like fifth position in ballet or a tap of the heel in Irish dance. “You can take her or leave her,” one of her early reviewers, Mary F. Watkins, wrote in 1931, “but you cannot divert that fixed gaze which looks so intently ahead into a world which is completely hers to explore.”

Though Graham collaborated with a small group of dancers, the technique she developed was meant to facilitate her own expression above all. She remained at the center of the dances, in the role of protagonist, until she was so crippled by arthritis that she could barely get around the stage. “I cannot go on without dancing,” she told a dancer who beseeched her to retire after a catastrophic performance at the age of seventy-six. “The love I receive from the faceless audience I cannot live without.”

Her technique was also built around her subject matter, weighty with ideas. Heretic (1929), one of the first works to reflect the new movement vocabulary she was developing, is about a woman who dares to challenge puritanical convention, represented by an unyielding wall of women clad in stretchy long black dresses that made them look like an art deco frieze. (Evocative costume design was another of her talents.) Twelve women crowd around the figure of Graham, who is dressed in white. They stomp their heels, arms rigidly at their sides or crossed before them. She breaks through their ranks, reaching upward, as if calling upon a higher power. Again they surround her, implacable. She faces them again, now on her knees. Again she is repelled. In the end her confidence is broken, and she collapses backward to the floor. “I felt at the time that I was a heretic,” Graham explained. “I did not dance the way other people danced.”

The music for Heretic, a Breton folk song selected and adapted for the dance by Graham’s first consequential lover and mentor, Louis Horst, a versatile musician who spurred her intellect and helped to round out her musical education, was spare and left long gaps for the dance to proceed in silence. The elimination of dance’s dependence on music was another tenet of Graham’s artistic philosophy. She applied this rule even on the few occasions, like Appalachian Spring, when she was using a truly great score. Graham often choreographed in silence, adding the music later. This idea—that dance and sound should remain independent—marked a definitive break in tradition that would alter the course of avant-garde dance and be expanded upon by choreographers like Merce Cunningham (who danced for a time in Graham’s company) and Trisha Brown.

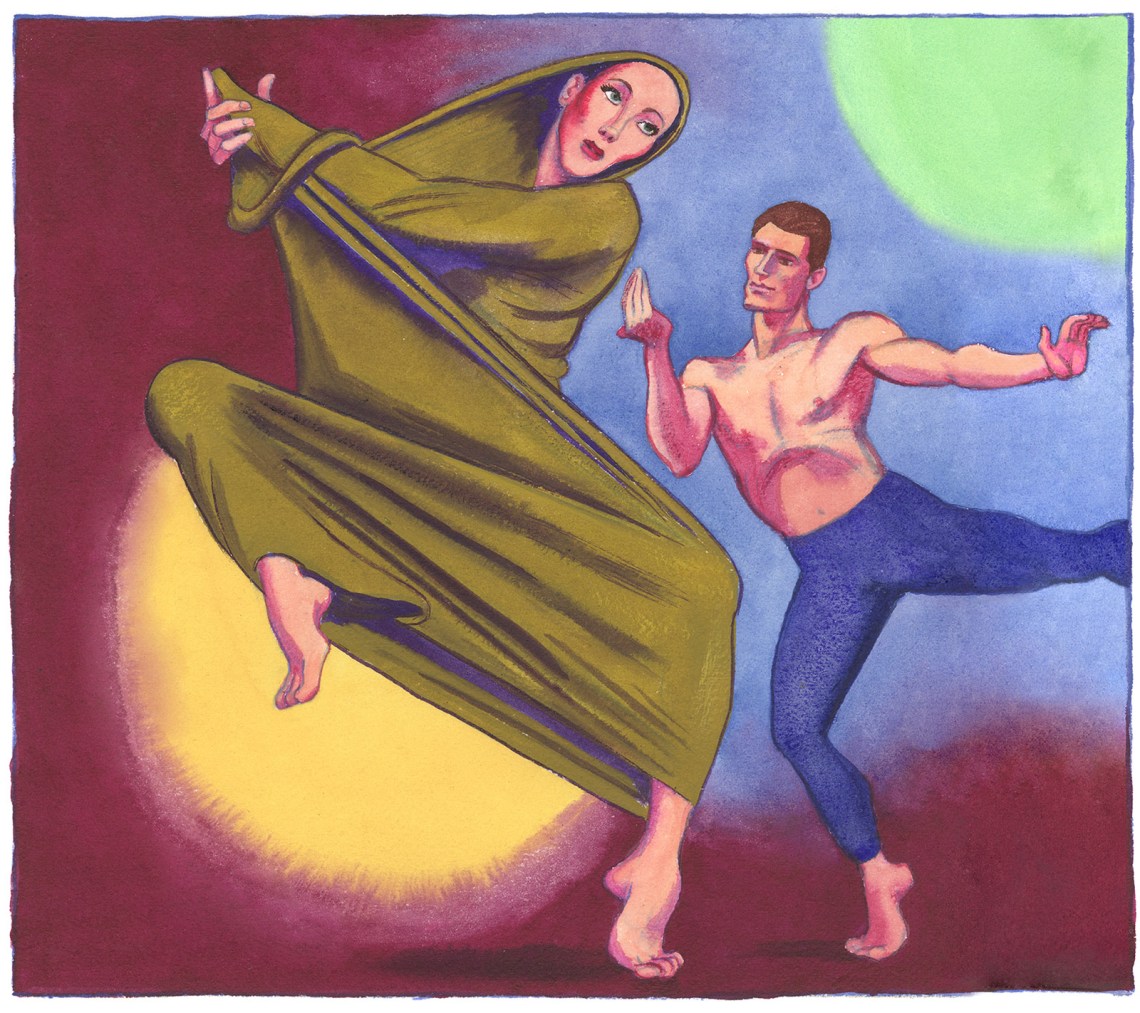

In Lamentation, Graham turned herself into a moving sculpture as she twisted and bent her body inside a tubelike cotton robe. Her contorted limbs and the stretch lines in the fabric formed a striking illustration of female sorrow. Primitive Mysteries (1931), which Jowitt calls Graham’s first masterpiece, drew on ceremonial Native American dances and processionals by the Penitentes, a Christian confraternity based in the American Southwest, which she visited with Horst as her guide. Graham, again dressed in white, fluttered across the stage, her movements contained by lines, circles, and wedges of women who alternated between gestures of protection, prayer, praise, and horror at their vision of Christ on the Cross. She was the Virgin Mary, and they were her acolytes. Near the end, one of the women created a halo of fingers around Graham’s head, as if prefiguring the Assumption. The music, a simple composition for flute, oboe, and piano, was by Horst, and was added later.

In the 1930s, as fascism rose in Europe and the Spanish Civil War raged, Graham’s work became more political, acquiring gestures of protest (Chronicle, 1936) and words (American Document, 1938). But in all these dances, and the ones that followed, a woman—Graham—stood at the center. The dances were about women and offered one woman’s—Graham’s—point of view. The image Graham projected was heroic, often tragic. “I think the Chosen One is the artist,” she said, after dancing in a version of The Rite of Spring in 1930. In her dances, she was always the Chosen One. In Letter to the World (1940) she was Emily Dickinson; in Deaths and Entrances (1943) one of the Brontë sisters; in Appalachian Spring the bride.

As her interest in Greek mythology and Jungian analysis grew—she was a voracious reader and took copious notes before beginning a dance—her range of roles expanded even further, from the embodiment of her own unconscious in Dark Meadow (1946) to Medea, Ariadne, Jocasta, and Phaedra. For these dances she collaborated with the sculptor and designer Isamu Noguchi, whose elemental and organic style suggested the shapes of the subterranean mind. Even in the works in which Graham did not dance, such as Seraphic Dialogue (1955), inspired by the visions of Joan of Arc, the heroine represented a version (or in this case, versions) of her. Over the course of each work, the heroine acquired self-knowledge. As Croce wrote, “No Graham heroine dies unillumined.”

What her post-1939 dances had in common, too, was the inclusion of men, and in particular of one man, Erick Hawkins, a dancer and choreographer fifteen years her junior. In 1938 he first danced with her company, and in 1939 he was officially incorporated into the troupe as its first male dancer. In short order Hawkins became Graham’s lover, partner, and, in 1948, her husband.

Hawkins was tall, handsome, and a good if somewhat stiff dancer. He was a thinker. He also had a temper. De Mille writes, “There was a roughness and a brutality, even savagery, in his nature that spoke to Martha.” Graham immediately saw him as her counterpart in the dances: he became the Husbandman to her Bride, the Jason to her Medea, the Oedipus to her Jocasta. Their separation in 1950 sent her into a spiral of depression and was one of the causes of her alcoholism, which grew ever more severe over the years and led to a health crisis in 1970. (She eventually weaned herself off drinking and died at ninety-six in 1991. Horst, who left the company in exasperation in 1948 but with whom she was able to mend fences, died in 1964.) The end of her relationship with Hawkins was the end of an important chapter for Graham. “There was never anyone after Erick,” she wrote in Blood Memory.

Their love affair was turbulent. Hawkins was presumptuous, high-handed, and the inferior artist. Graham was manipulative, painfully aware of his inferiority, and sometimes cruel. He managed the company for her, and she used him for all sorts of menial tasks. More importantly, she was fundamentally unwilling to share her starring place in the company and in the dances, which Hawkins could not accept. “I want to be able to perform completely on my own and as an equal in M’s company,” he wrote in his journal. He wanted these things despite the fact that his dances were generally poorly received and that the dancers and audience were there because of her work, not his.

Hawkins thought that marrying Graham would elevate him in her eyes and the eyes of the company. Fearing exactly this—she had seen a similar dynamic destroy St. Denis—Graham had always avoided tying herself to a man. She married Hawkins in a moment of weakness after a quarrel and two years before their definitive separation. But she was fundamentally opposed to the institution of marriage. As Mark Franko writes in Martha Graham in Love and War, “Graham saw all women as trapped in the patriarchal prison of marriage leading to childbirth. Her resistance to marriage was a life and death struggle for her own artistic identity.”

“Their relationship affected the life of the company and occasionally tested her authority,” Jowitt writes. (An understatement if ever there was one.) All Graham’s biographers deal at length with her fraught relation with Hawkins, but Jowitt is perhaps the least interested in its Sturm und Drang and how it molded the dances. In Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern (2022), Neil Baldwin places perhaps too much importance on it, ending his otherwise engaging portrait of Graham just after their separation and relegating four decades of dances to a couple of sentences. (Baldwin is more generous toward Hawkins than most and does him the favor of taking his artistic ideas and aspirations seriously.) De Mille seethes with contempt for him, and she dwells with the most fervor and antipathy on the effects of the Graham–Hawkins entanglement on the company’s morale and eventually on Graham’s self-confidence. She is perhaps a touch unfair. Helen McGehee, who joined the company in the 1940s and stayed for decades, defended Hawkins in a review of de Mille’s book, to a point: “I came to realise that Martha was transferring a lot of the blame for actions that fretted the company from herself to Erick, all the while defending him tooth and claw.”

What is inarguable is that this conflicted sexual passion was poured into the bloodred heart of Graham’s dances. After Hawkins entered her life and company, the heroines were no longer lonesome warriors; their triumphs and dramas became contingent on their relations, fulfilling or destructive, with a male figure. “Her dancing became fraught with sexuality and passion,” de Mille writes. Sex mattered, and was alluded to with a frankness that is still bracing today. Joan Acocella wrote, “It wasn’t just Greek mythology; it was Graham’s life. The treatment varied. In Appalachian Spring, Graham showed us happy sex; in Night Journey tragic sex; in Letter to the World sex refused. Graham never had much fear of sex.” This was not subtext. In Night Journey, a dance in which Jocasta remembers her sexual passion for a man who turns out to be her son, Graham crossed her knees daintily, opened them, closed them, and opened them again. She later called this gesture an invitation “into the privacy of her body…a gesture of invitation for him to come between her legs.” At another moment in the same dance, her torso contracted at Oedipus’s touch; she described this as “the cry from her vagina.” Graham was known to tell her dancers to “dance from the vagina,” a demand that even the male dancers were expected to follow.

The preoccupation with the sexual forces that bind men and women together extended to her use of the other male dancers in her company as well, though with less intensity. In the lighthearted Every Soul Is a Circus (1939), she acted out her attraction to two very different male figures danced by Hawkins and the young Merce Cunningham, who had recently joined the company and who, as a gay man, was beyond her reach. The men often wore very little, and their roles lacked the psychological complexity of the women’s. (The latter was one of Hawkins’s complaints.) The choreographer Paul Taylor, who danced for Graham in the 1950s and early 1960s, joked about the objectification he felt as a male member of the company:

With Martha, the men were the equivalent of a male Barbie doll…. We were sticklike figures who were basically sex objects. We didn’t dare say anything. In fact, I think we kind of liked it.

Take that, men. Graham’s dances were the manifestation of the female gaze in its purest form. The strength required to be a woman artist, the banishment of doubt needed to keep going in the face of incomprehension, the place of desire in the creative act, the need, too, for love—all this is the material of her dances. In Errand into the Maze Jowitt explains them to us with the clarity of a critic experienced in looking intently at dance. But if you want to get a sense of what it was like to be around Graham, to sit at her feet and learn her movement language even as she tore it out of her gut, to suffer her rages, and to see the tumultuous effect of her passions, you might want to look at de Mille’s Martha as well.