“Newspapers are only as good as the ideas and information they succeed in conveying. And this means not only putting facts down on paper, but doing so in such a way that they get off the paper and, in a meaningful and orderly fashion, into the minds of the readers.” When I read these admirable sentiments in an editorial in the New York Herald-Tribune of April 19th last, I was puzzled because the day before the Tribune’s Sunday magazine had published the second of two articles on The New Yorker by Tom Wolfe which seemed to me extreme examples of the opposite: their ideas bogus, their information largely misinformation, their facts often non-facts and the style in which they were communicated to the reader neither orderly nor meaningful.

Was this an Aesopian apology by some of the Tribune’s editors, I wondered, for what their colleagues on the Sunday edition had just been up to? Or was the emphasis on getting facts “off the paper and into the minds of the readers”—or rather into their cortical reflexes, for Wolfe’s bazooka aims lower than the cerebrum—a justification of his kind of reportage, so much more readable and, hopefully, sellable than the fact-bound approach of the Tribune’s great solid successful competitor. Whatever its intent, the editorial suggests the Tribune’s dilemma, caught between deficits and respectability. “Who Says a Good Newspaper Has to be Dull?” its ads used to ask, with a sideglance at the Times. Dropping the first adjective isn’t the answer.

Reviewing a collection of Tom Wolfe’s articles in this paper last August, I considered them as examples of a new kind of reporting that has become widespread, namely, “parajournalism,” a bastard form that has it both ways, “exploiting the factual authority of journalism and the atmospheric license of fiction.” The articles on The New Yorker, which were not in the book, carry the genre to its ultimate of illegitimacy, or what I hope is such: the free-form shaping of an Image in the manner of a press agent with fewer inhibitions about accuracy than obtains in the more reputable public relations firms. I think it worth examining them in some detail.

The first article is headed: “Tiny Mummies! The True Story of 43rd Street’s Land of the Walking Dead!”—a jocose echo of Bernarr MacFaddea’s Daily Graphic, whose “bogusity” and “aesthetique du schlock” Wolfe admires: “But by god the whole thing had style.” Or of the extant National Enquirer (“Jimmy Cagney Admits: I HATE GUNS”). Some interpret the whole thing as a spoof—the author when pressed on humdrum matters of fact edges in this direction—but the theory breaks down because there are distinct traces of research. A parodist is licensed to invent and Tom Wolfe is not the man to turn down any poetic licentiousness that is going. He takes the middle course, shifting gears between fact and fantasy, spoof and reportage, until nobody knows which end is, at the moment, up.

Omerta! [he begins] Sealed lips! Sealed lips, ladies and gentlemen! Our thing!…. For weeks the editors of The New Yorker have been circulating a warning among their employes saying that some one is out to write an article about The New Yorker. This warning tells them, remember: Omerta. Your vow of silence….

One wouldn’t even have known about the warning…except that they put it in writing, in memos. They have a compulsion in The New Yorker offices, at 25 West 43rd Street, to put everything in writing. They have boys over there on the 19th and 20th floors, the editorial offices, practically caroming off each other…because of the fantastic traffic in memos. They just call them boys. “Boy, will you take this, please….” Actually, a lot of them are old men with starched white collars…[who] were boys when they started on the job, but the thing is, The New Yorker is 40 years old…[and] they all have seniority, like Pennsylvania Railroad conductors.

The paper the thousands of messages are on is a terrific rag-fiber paper…. Manuscripts are typed on maize-yellow bond, bud green is for blah-blah-blah, fuchsia demure is for blah-blah-blah, Newboy blue is for blah-blah-blah, and this great cerise, a kind of mild cherry red, is for urgent messages…

This Issue

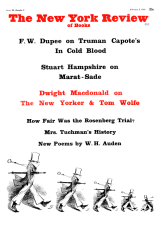

February 3, 1966

-

1

Her book, of course, is not part of any “court records,” and her quotations from the Bowman-Hulbert Report, to which Volume 9 of the record described above is devoted, despite her claim that “These reports are quoted in full, except for the unprintable matter,” do not agree with Volume 9. She reprints only a small portion of its 302 pages. The stylistic variations between what she calls full quotations and the psychiatrists’ report there are considerable.

↩ -

2

As Hannah Arendt wrote, in a letter the Tribune didn’t print: “The editor is guilty of a ‘passion for anonymity’, of love for perfection and dedication to his work, of competence, refinement, courtesy and modesty. These qualities ‘add up’ to qualifying him for burying the dead. What then must I do, according to your author, to prove I am alive? I must be vain, blow my own horn, use my elbows, be inconsiderate and above all not polite: my lack of manners, my shouting will wake up the dead! . Your author goes on. ‘One means well, of course.’ But this is not a matter of course in literary circles. That to mean well is a matter of course in the offices of The New Yorker belongs among the many qualities that make the magazine unique.”

↩ -

3

I found few usable items for my Parodies anthology, for instance, in the hundred years of Punch, whose humor has always tended to be rather broad, and square, which may be why none of the great English parodists, from Calverley to Beerbohm, published much there. The New Yorker, on the other hand, was my chief source for modern parodies.

↩ -

4

For the figures in this paragraph I am indebted to Gerald Jonas, as I am to Renata Adler for some of the material on the Loeb-Leopold case. Both are colleagues of mine at The New Yorker and have written a factual analysis of Wolfe’s articles on The New Yorker which will appear in the Winter, 1966, number of the Columbia Journalism Review, along with an evaluation by Leonard Lewin of the journalistic implications of the affair for the Tribune.

↩