In one respect at least the very different books by Simon Schama and George Rudé have something in common: each is based on the reinterpretation of old evidence rather than on new discoveries. They incorporate a kind of tribute to their authors’ student days. In Rudé’s case this implies very heavy dependence on the French Marxist historian Georges Lefebvre: “I have followed fairly closely the arguments of G. Lefebvre”; he is “greatly indebted” to Lefebvre’s “masterly portrayal” of Napoleon; “the best work on the outbreak of the Revolution is still G. Lefebvre’s”; for the social and economic history of the Revolution one should consult “above all,…the work of Georges Lefebvre.” What influences Simon Schama is not so much a man as a syllabus. As one reads his book one hears the roll call of the old Oxford University “special subject,” in which the student has to read, among other books, the memoirs of the Marquis de Ferrières, the correspondence between Mirabeau and the Comte de La Marck, the letters exchanged between Barnave and Queen Marie Antoinette, Morse Stephens’s selections from the French revolutionary orators.

There is nothing in the least reprehensible about this. Lefebvre was an excellent historian and primary sources have a perennial value. But anyone writing in 1989 needs to take account of more recent research. Both authors are rather hit-and-miss about this. Rudé’s bibliography is better on old books than on those published within the past twenty years. Schama is more familiar with recent work, but he seems to have read very selectively. When Rudé mentions a book that contradicts his argument—which is not often—he is invariably courteous to its author even if he does not always seem to have understood his message. Schama acknowledges his debt to the authors of recent studies on matters of detail, but he is rather fond of admonishing unnamed “historians” for distorting the evidence to fit their preconceived conclusions.

Neither writer has anything substantial to say about Jacobin ideology as a force inclining the Revolution toward totalitarianism, and they fail to see that peasant society was largely motivated by a conception of the world that had little in common with the enlightened abstractions of the revolutionary legislators. These are things that have come to appear in a new light as a result of the work of historians such as François Furet, Robert Darnton, Donald Sutherland, Colin Lucas, and Peter Jones. If Rudé and Schama are aware of such work, they do not pay much attention to its conclusions.

In all other respects their books are as different as one could imagine. Rudé writes as an old professional who has been on active service in the field since the publication in 1959 of his book on revolutionary crowds. Schama is certainly not an apprentice historian, but this is his first venture on the embattled terrain of the French Revolution. Rudé’s book is somewhat austere and very short: he hustles us through the Revolution and Napoleon and well into the nineteenth century in a mere 182 pages. After three hundred lavishly illustrated pages of his own, Schama has barely reached 1789, and he never goes beyond 1794. Rudé is mainly concerned with analyzing the political behavior of social classes; Schama spends much of his time on personalities, and in his account of events it is people that makes them happen. Whereas Rudé sees men essentially as cognitive animals Schama is more aware of the role of emotion and the power of symbols.

When it comes to the basic question of what the Revolution achieved and why it evolved in the way it did, the two men flatly contradict each other. For Rudé, despite all its blemishes and frustrations, the Revolution left behind a glorious message of social progress that was to inspire future generations. The liberal revolution of 1789 was only consolidated with the help of urban artisans or sansculottes, which meant that it already looked forward to a socialist future. Schama sees the Revolution as a total disaster, in which the violence and chauvinism of a reactionary mob put an end to an ancien régime that was already liberal in essence and fully committed to technological progress. With the best will in the world it is difficult to see how they can both be right, and the reader is faced with the question of what to make of the situation when two serious professional historians study the same events and arrive at such incompatible conclusions. This calls for a careful examination of each book in turn.

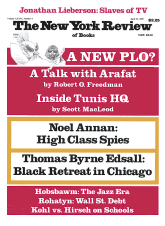

This Issue

April 13, 1989

-

*

Verso, 1987.

↩