A strong ideological fixation is not a promising basis for a responsible foreign policy. During their first four years, President George W. Bush and his administration made intransigent unilateralism, American exceptionalism, and preemptive military action the watchwords of United States foreign policy, with abysmal results. The position of the United States in the world was drastically weakened. The unique respect and the authority as a world leader that the US had enjoyed since World War II were severely compromised, and the US military establishment was overstretched without achieving any strategic advantage.

The tone and style of America’s voice in foreign affairs became arrogant and brash, as if its leaders were shouting at the world at large their supremacy and their thinly concealed contempt. The invasion of Iraq quickly became a bloody nightmare, draining essential resources from the pacification and reconstruction of Afghanistan. The isolation and resulting ineffectiveness of the secretary of state, Colin Powell, certainly contributed to this dismal record.

In Bush’s second term both the policy and the tone began perceptibly to change. An overindulged secretary of defense eventually resigned and the administration was chastened by the growing bloodshed and chaos in Iraq and the unpopularity of the war in the US. Condoleezza Rice, as the new secretary of state and one of the President’s most trusted advisers and friends, was able to take some steps to revive US diplomacy, particularly in relations with North Korea. The idea that it was important to talk, at least in a limited way, to those perceived as enemies or potential enemies and to make some effort to understand their concerns and their interests began, if intermittently, to gain ground. Whether a consistent and comprehensive foreign policy, no longer intoxicated by ideological or neo-imperial fantasy, will emerge from this change of attitude is far from clear.

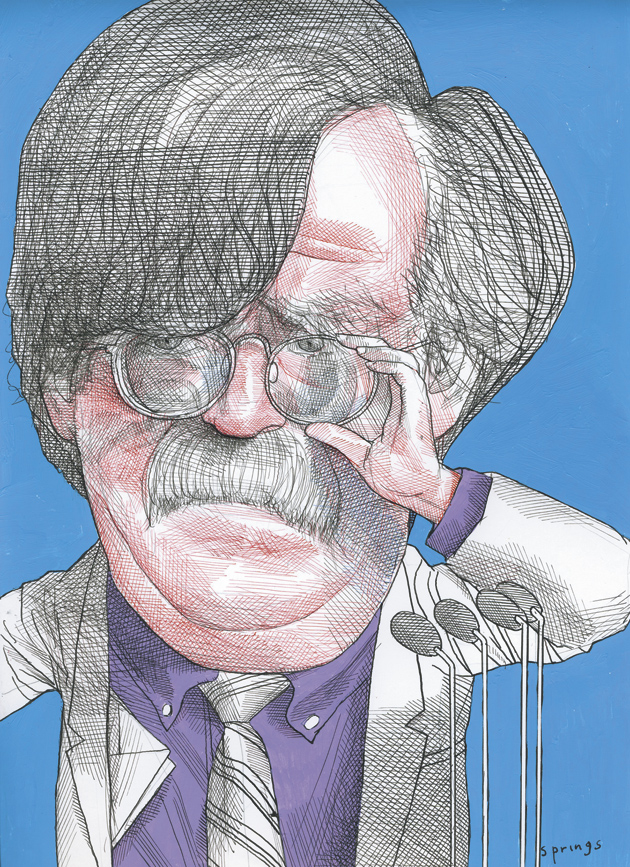

At least one former senior state department official has strongly deplored the change in the manner and substance of Bush’s foreign policy. More than one half of John Bolton’s memoir is taken up with the seventeen months he spent as US ambassador to the United Nations during Bush’s second term. He now reveals how unhappy he was with the Bush administration’s changing approach throughout his time at the UN. His single-minded career of dissent now includes opposition to the Republican administration with which he signed up in 2000.

At first sight, the title of Bolton’s book seems to raise a fundamental, and awkward, question. Is the United States still a benevolent superpower, capable, at its best, of leading the world into a decent future? Or is it, as Bolton’s title at first seems to suggest, a threatened, defeatist giant, betrayed by liberals and “the left” at home, and constantly on the defensive against deadly enemies and uncertain friends abroad? Only later on in the book does Bolton explain that the phrase “Surrender is not an option” refers to abandoning political principles. There is no doubt about Bolton’s vision of himself as the dauntless defender of US principles as he sees them.

Bolton is not a neocon. His political passions were ignited in his teens by Barry Goldwater, and he has always been a “libertarian conservative.” He thinks that “our emphasis must be more on liberty than democracy… the first being freedom from government, the second being one way to select governments.”1 It is small wonder that he doesn’t much like the United Nations, which consists of 192 governments. It says much about the Bush administration that someone with his views could be appointed UN ambassador.

Ideological consistency and his passionately held version of the national interest have driven Bolton’s career. The son of a Baltimore fireman, he did well at Yale, where he was a member of a very small conservative minority, feeling like “a space alien” among the late-1960s crowd of anti–Vietnam War activists. He resented being urged by these rich, liberal young men to join in their antiwar activities. “The conservative underground is alive and well here,” he told a Class Day Vietnam debate; “if we do not make our influence felt, rest assured we will in the real world.”

As to actually serving in the Vietnam War, Bolton decided, in 1970, that the war was already lost, so he “wasn’t going to waste time on a futile struggle”; faced with the draft, he, like George W. Bush, managed to join the National Guard. Thus, after graduating summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, he entered Yale Law School, where Clarence Thomas was his classmate and friend. Bill and Hillary Clinton were also among his classmates, but he “didn’t run in their circles.”

Bolton spent his first adult years, during the Carter administration, in private practice, waiting for the political tide to turn. Despite the prospect of becoming a partner in a highly regarded law firm, he found work in the Reagan administration in the Agency for International Development (AID) where, by canceling unsuccessful projects, he was able to present to Reagan, in the Rose Garden, a refund check for $28 million. At the AID Bolton was surprised at what he perceived as the impertinence of some governments in their dealings with the United States. “I never understood why the United States was expected to be a well-bred doormat.”

Advertisement

As assistant secretary of state for international organization affairs in the George H.W. Bush administration, Bolton’s distaste for multilateral organizations steadily grew. He regarded the UN itself as the “hopeless captive of Soviet manipulation and Third World radicalism.” (A mirror image of this view, the UN as the lackey of the United States, was current on the other side of the Iron Curtain.) In Bolton’s view, only the Security Council, where the United States has a veto, was an international institution of real importance.

After the 2000 election Bolton rushed to Florida to support the Bush legal team in the dispute over the vote recount. His thirty-one days in Florida—“one of the great emotional roller-coaster rides of my professional life”—became a kind of founders’ badge of allegiance to the new administration. Six years later, leaving government service for private life, he could only condemn the new moderation of the Bush administration’s foreign policy: “I didn’t spend 31 days in Florida to end up where we are now.”2

Bolton is wary of both treaties and international law. He quotes De Gaulle’s fatuous remark, “Treaties, you see, are like girls and roses: they last while they last,” adding that “I saw treaties as essentially only political documents.” As for international law, Bolton writes with ponderous disdain of a possible US violation “of (say this in a slow, deep voice) ‘international law,’ which of course would be a Bad Thing.”

As undersecretary of state for arms control and international security affairs during the first term of the George W. Bush administration, Bolton was well placed to demolish international agreements and treaties. He rationalizes this activity with the observation, “…We were simply rejecting inferior policies and agreements, and replacing them with greater American independence and fewer unnecessary constraints.” He engineered the US withdrawal from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty—“a Cold War relic that essentially precluded both Russia and the US from developing national missile defense systems.” Citing the events of September 11 as justification, he also worked to derail the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in order to prepare the way for new American nuclear testing. Under the preposterous subheading “Foiling International Gun Control at the UN,” Bolton describes his half-successful attempt to undercut the UN conference on small arms and light weapons (still the world’s foremost killers), alleging that it was, among other things, an effort by the American left and NGOs to strengthen attempts at gun control in the US.

Bolton’s most-hated bête noire was the International Criminal Court (ICC). “My happiest moment at State,” he writes, “was personally ‘unsigning’ the Rome Statute,” which set up the court. He was furious that the Security Council, desperate for some action that would mitigate the disaster in Darfur, had asked the ICC to consider if prosecutions for crimes against humanity might be possible there. He alleges that this was a European plot to create a precedent for future use of the court and to make the US lose face by forcing it to abstain on the decision. He mounted a global campaign to extort assurances from nearly one hundred governments that they would not surrender any American to the ICC. (Under the statute of the ICC this was an unlikely contingency.3 ) These and other of Bolton’s achievements as undersecretary did much to undermine America’s leadership and position in the world.

At the outset of the second Bush term, the new secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice, asked Bolton what job might interest him in the new term. Bolton’s mention of his interest in being deputy secretary of state was received with no enthusiasm, and two months later, in March 2005, Rice announced his nomination as ambassador to the UN, thus appointing to this unique post the US official most publicly contemptuous of the world organization. Bolton’s long and abrasive confirmation hearings before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee were, in his own words, not so much about the UN or his opinions, but about “whether I was a nice person, thereby inviting every person in government whom I had ever defeated in a policy battle, of whom there were many, to turn the issue into one of personal disparagement….” Even though Republicans held a majority at the time, his confirmation failed by four votes in the Senate. The President finally announced his recess appointment on August 1, 2005.

Advertisement

Arriving in New York one month before the summit meeting of heads of state and government on the UN’s sixtieth anniversary, Bolton, who disliked both the UN’s declarations on global problems and the UN Secretariat and the secretary-general, Kofi Annan, took particular exception to the draft of the summit declaration. UN delegations, including the United States, and the Secretariat had for the previous six months been working on this document, which originally contained a fairly ambitious mixture of global objectives and UN reform proposals. Bolton’s seven hundred or so amendments, designed, he believed, to increase the influence and reflect the interests of the United States, caused considerable confusion and resentment and reopened many disagreements that had previously been resolved. Among other things, he insisted that there be no mention of the Millennium Development Goals to eradicate global poverty, which the US had supported in 2000. (Condoleezza Rice overruled Bolton on this at the last minute.) Bolton also insisted on the elimination of any mention of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, the ICC, and global warming.

Contempt and anger are Bolton’s normal reactions to disagreement. He denounces even small differences of opinion in abrasive, ad hominem language, saying of his British counterpart, for example, that, watching him in action, “I often wondered how the British had acquired an empire, although he proved why they had lost America.” His chapter headings—“Arriving at the UN: Fear and Loathing in New York,” “Iran in the Security Council: The EU-3 Find New Ways to Give In,” “Israel and Lebanon: Surrender as a Matter of High Principle at the UN”—give some indication of his scorn for most of the people and institutions he was dealing with.

The European Union and “its deadening Brussels bureaucracies” are natural targets for a libertarian conservative, and Bolton misses no opportunity to deride the “Euroids,” reserving special disdain for British diplomats. But the group that earns Bolton’s deepest wrath is the UN Secretariat and its secretary-general.4 He seems unable to mention Kofi Annan’s name without a snide, and often wholly unfounded, slur; for example, about Annan’s understandable reservations about a public Security Council debate on alleged corruption and sexual abuses by UN peacekeepers, there was, he said, a “deeper problem of Annan’s deviousness, but this time he had been caught.” He states that the only really effective reform of the UN would be to make governmental contributions to its budget entirely voluntary. (One wonders how an entirely voluntary taxation system would work in the US.)

Annan “was simply not up to the job,” Bolton states contrary to the general opinion and without explanation. But neither Powell nor Rice was prepared to try to remove him. In fact Rice is quoted as saying, “I’ve never had a better relationship with anyone than I’ve had with Kofi Annan.” On the emergency Oil-for-Food program in Iraq, for which UN administration and lack of supervision were rightly criticized, Bolton recites the standard neoconservative denunciation of Annan and the Secretariat without mentioning who was responsible for the real scandal. It was the Security Council, including the US, that allowed Saddam Hussein’s government to negotiate deals and kickbacks directly—without UN supervision—with the hundreds of commercial firms involved. Nor does he mention that the US and the four other permanent members of the Security Council turned a blind eye to Iraqi oil smuggling to Turkey, Jordan, and Syria that accounted for most of Saddam’s illicit gains and had nothing to do with the Oil-for-Food program. He also fails to mention that the program successfully fed and provided essential supplies to some 25 million Iraqis for over six years, and thus made it possible to maintain the strict sanctions on Iraq as the United States and others wished.5

Bolton apparently resented Annan’s high reputation with most governments and his introduction of new principles and goals—for example, the responsibility of governments in the UN to protect desperate groups of people from violation of their human rights or persecution, even if their own government is the persecutor. Bolton refers contemptuously to this concept, now horribly relevant in Darfur, as “the High Minded cause du jour.”

Bolton also complains that Annan was “consistently unhelpful” after the US invasion of Iraq, an action which the Security Council had refused to support. He does not mention that Annan sent his own representative, Lakhdar Brahimi, to help the US occupation authority in assembling the first Iraqi Governing Council. Nor does he mention—and it is a particularly discreditable omission—that Sergio Vieira de Mello, one of Annan’s most valuable and respected senior officials, with fifteen of his staff and seven civilians were killed at the UN headquarters in Baghdad by a truck bomb in August 2003. Nor would you know from his book that the UN organized the elections in Iraq. As his ultimate insult, Bolton writes that Annan was “everything the Clinton administration could ask for: an international bureaucrat whose very career embodied their worship of multilateralism for its own sake.” The UN is, it might be recalled, an international organization of 192 states that was largely conceived by the United States; it is not a branch of the US State Department.

The Security Council is the only part of the UN for which Bolton had any use. “The General Assembly and ECOSOC [the Economic and Social Council],” he writes, “served only to consume oxygen and paper.” One of the most important tasks of the Security Council during Bolton’s UN stay was to recommend a successor to Kofi Annan. His hatred for Annan seems to have inspired Bolton to hope for a successor as unlike Annan as possible. By June 2006, according to Bolton, Secretary Rice had a “short list” of one name: Ban Ki-moon of South Korea. With characteristic cynicism, Bolton quotes Rice as saying at the time, “I’m not sure we want a strong secretary general,” a remark presumably not intended for publication, and a gross disservice to his and Rice’s chosen candidate.

Bolton maintains, rightly enough, that the selection of the secretary-general is a matter essentially for the five permanent members, although “the High Minded are always exhorting the UN to conduct an ‘open and transparent job search’ with ‘broad consultation’ and discussion, as if we were not making an intensely political decision.” Bolton has much to say about the shortcomings of the UN Secretariat and how the secretary-general should concentrate on improving the administrative side of the UN. The revolutionary idea of looking for the best person for the job does not seem to have occurred to him.

Reading Bolton’s petty account, it is worth recalling the long list of distinguished US representatives to the UN, public figures like Adlai Stevenson, Henry Cabot Lodge, or Daniel Patrick Moynihan and also superb professionals such as Charles Yost, who served in the late Sixties, or Thomas Pickering at the time of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Most governments try to send their ablest people to represent them at the UN. From this point of view, Bolton was, to put it mildly, a strange choice, as some of his fellow Republicans came to recognize.

Throughout 2006 Bolton was lobbying in Washington for the Senate confirmation that would allow him to continue at the UN in 2007. Despite much assistance, including that of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, which had also helped him in previous confirmation battles, there was no sign that a favorable Senate vote would be forthcoming. He therefore decided, he writes, to leave the administration and “keep firing” from outside it. “So in the cost-benefit calculus of being in the government,” he told The New York Times, “I just felt that on policy terms I could do more outside the government than within.”6 Bolton is now a favorite, and highly available, commentator to reporters writing for, among other outlets, The New York Times. Few stories on Iran, the Middle East, or North Korea are complete without an oracular but negative final comment from Bolton, who is now based at the American Enterprise Institute. Reporters seem to feel that if they quote him, they will have included a “tough” conservative point of view.7

Bolton constantly inveighs against the danger of prolonged negotiations, of diplomatic contacts, and of “rewarding bad behavior” when dealing with “Evil” governments such as those of North Korea or Iran. This partly accounts for his pungently expressed disgust with European diplomats, his allergic reaction to most UN officials, and his disagreements with the State Department. It has recently been announced that North Korea has begun to dismantle its nuclear weapons program and that Iran abandoned its nuclear weapons program four years ago. The patient negotiators whom Bolton so despises seem to have been doing a reasonable job after all. (He continues to denigrate the apparently successful efforts of the State Department’s Chris Hill to persuade the North Koreans to forgo nuclear weapons programs.)

Not surprisingly, Bolton’s stubbornly held opinions often involved him in arguments and even rows, which he appears to enjoy in a joyless sort of way. His epithets map out the vast landscape of his disapproval: The High Minded, The True Believers, Candle Lighters, Crusaders of Compromise, The Weak-kneed, The Chattering Class, Euroids, Mattress Mice, EAPeasers (members of the State Department’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs), and so on.

Bolton makes much of his tireless devotion to his work and his disdain for the allegedly frivolous and pleasure-loving attitudes of those he works with. When a meeting in New York has to be prolonged, for instance, he writes, “New York has a lot of shopping and cultural opportunities that cannot be fully enjoyed in a one-week conference.” Or, during the war in Lebanon in the summer of 2006, when the Security Council was in frequent session, he comments, “This being Friday, of course, what really concerned most other delegations was whether they would be able to go to the Hamptons for the weekend.” According to the UN Charter, the Security Council is “to be so organized as to be able to function continuously,” and it has always done so, if necessary all night and over weekends. Its members are quite used to this admittedly demanding routine. Bolton’s claim that “most other delegations” were concerned about weekends in “the Hamptons” is the kind of patronizing fantasy that occurs all too frequently in his book.

Bolton tempers his growing disillusionment with Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice with a politeness not extended to others. He deplores the culture of the State Department, whose members he holds responsible for “the large and growing list of wrong directions and mistakes…on Iran, North Korea, the Middle East, and others.” The department, he writes, is too full of liberals and the High Minded and needs a wholesale cultural revolution. Bolton also comments in passing that “presidential ineptitude cannot be ignored.” Some of Bush’s appointees, he implies, cannot stand up to the career bureaucracy.

In his self-imposed isolation, Bolton sometimes calls to mind those retired British officers, immortalized in the cartoonist David Low’s Colonel Blimp, who took satisfaction in insisting that “lesser breeds” could be dealt with only by a stiff dose of military force. He often seems unaware that the time for imperial arrogance, bluff, and gunboat diplomacy has long passed. Addressing foreign governments and peoples in insulting and high-handed terms—the “Axis of Evil,” for example—no longer intimidates them; it enrages them and only increases support for extremists and extreme policies.

The use of overwhelmingly superior conventional force has, in most situations, become an anachronism that creates violent opposition without gaining its intended objective. William Pfaff described this development well, writing in 1998 that

the belief that America as “sole superpower” would or could dominate the world, widely held after communism’s collapse, rested on the illusion that military and economic power directly translate into political power, and that power is identical with authority. The exercise of authority requires consent, and rests on a moral position.

While advocating a hard line, Bolton is careful not to specify how in the end to put into effect the “tough” approach he favors. He avoids mentioning the use of force but employs instead phrases like “serious efforts” or “actually doing something.” He sometimes goes so far as to say, in the cases of Iran and North Korea, for example, that “regime change” is really the only acceptable solution, without saying how regime change might be brought about without war. Bolton barely mentions Iraq and Afghanistan, the contemporary tests of conventional military force in pursuit of regime change, except to say that he had nothing officially to do with Iraq, but if he had, he would probably have been in the same camp as his friends Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld. (He misses, he tells us, Rumsfeld’s “strong voice and sound opinions.” Rumsfeld liked to call Bolton “Mr. Hanging Chad,” in tribute to Bolton’s prowess in the Florida recount battle.)

Bolton and his small band of co-ideologues apparently see themselves as fighting virtually alone against the forces of evil, compromise, and weakness. As far as foreign affairs are concerned, their beliefs seem to be roughly as follows:

United States interests alone are to be considered as paramount; the United Nations is only relevant insofar as it serves those interests.

Foreigners, even some supposed allies, cannot be trusted, and the hostile ones (North Korea, Iran, the enemies of Israel, and others) will always cheat, will never abide by an agreement, and only understand pressure and force.

With such people there should be only sticks and hard words, no carrots, no rewards for good behavior, and no prolonged negotiations. Force always remains an option.

The High Minded, Liberals, multilateralists, and most Democrats are, in their own way, almost as destructive as hostile foreigners.

Such views could be regarded merely as colorful and anachronistic eccentricities if they were not voiced by someone who has held important public positions and who is therefore still regarded by many people as an expert. From such a source, they contribute seriously to weakening, not strengthening, the position of the United States in the world. For all John Bolton’s undeniable ability and strength of mind, his views and his style are a luxury the United States can no longer afford.

This Issue

March 6, 2008

-

1

“What Kind of War Are We Fighting, and Can We Win It?,” Commentary, November 2007. ↩

-

2

Steven Lee Myers, “Bush Loyalist Now Sees a White House Dangerously Soft on Iran and North Korea,” The New York Times, November 9, 2007. ↩

-

3

105 governments are now parties to the Rome Statute. ↩

-

4

Like his other opinions, Bolton’s position in favor of the policies of the state of Israel seems absolute—more so than that of a great number of Israelis. Any criticism of Israel’s policies or actions is to him hostile to Israel itself, a serious accusation that he levels at the UN Secretariat. It is true that Security Council or General Assembly resolutions—on Israeli occupation of Palestinian or Arab lands, for example—have often been called anti-Israel, especially in the United States. ↩

-

5

See my “The UN Oil-for-Food Program: Who Is Guilty?” The New York Review, February 9, 2006. The Volcker report on the Oil-for-Food Program, which Bolton calls “devastating” for the UN, states, “The Committee also believes that the successes of the Programme, although not extensively chronicled here, should not be buried by the allegations of corruption that have enjoyed so much attention in the media and elsewhere” (Vol. 1, p.13). ↩

-

6

Myers, “Bush Loyalist Sees a White House Dangerously Soft on Iran and North Korea.” ↩

-

7

The most recent example is the statement in The New York Sun of January 23 that Bolton, at a conference in Herzliya, “warned Israelis that the Bush administration is unlikely to act to halt Tehran’s nuclear race, and he urged Jerusalem to strike militarily.” ↩