One inescapable principle highlighted by the current financial crisis in the United States is that a democracy gets the regulation it chooses. If voters elect public officials who do not believe in regulation, and if those officials appoint people of like mind to lead the key agencies that make up the nation’s regulatory apparatus, then there will not be effective regulation no matter what the prevailing statutes say.

A further lesson of the crisis, which makes this basic principle of democratic governance crucially important, is that self-regulation by private firms—what many of the opponents of government regulation from Alan Greenspan on down were counting on to take its place—is insufficient to meet the challenges presented by today’s complex financial markets. Two hundred years ago, when the English economist Henry Thornton was setting forth the fundamental principles of central banking, all London banks other than the Bank of England had to be partnerships in which each partner was legally responsible for the bank’s obligations; no other “joint stock banks” were permitted. (Further, the maximum number of partners was six.

Today’s financial firms are limited- liability corporations owned by what are often widely dispersed stockholders. And these firms, whose chief economic function is to provide capital to households and nonfinancial businesses, are themselves highly dependent on competitive securities markets to raise their own capital. When the crisis hit, the typical leverage of a large US commercial bank (the ratio of its debts and other liabilities to its stockholders’ equity) was twelve or fifteen to one. At the large investment banks, leverage was more like twenty-five or thirty to one.

The combination of limited liability, widely dispersed stock ownership, and high leverage turns out to be fundamentally subversive of market self- regulation. With limited liability, even if stockholders manage the firm directly—even if the firm has only one owner who manages it himself—the incentive to take excessive risk is already present. The bigger the bet, the more stockholders stand to gain if the coin comes up heads. If the bet goes wrong, once the stockholders’ equity is gone, bigger losses accrue only to whoever holds the firm’s debts or other liabilities (or to the taxpayer, if the government comes to the rescue).

Widely dispersed stock ownership, which is also typical of most large US corporations today, compounds the problem. The traditional notion of corporate governance exercised by a board of directors, acting in the interests of the stockholders, has long been a fiction for many firms. But many fictions are useful ones. No one should be surprised that the primary concern for most corporate executives is how well they do—their job security, their pay, their perks, their prestige—not how well the stockholders do. If, however, what benefits the managers and what benefits the stockholders are sufficiently similar, the difference doesn’t matter much.

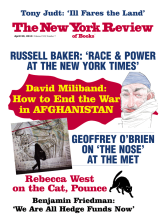

This Issue

April 29, 2010

-

1

I am grateful to Kevin Hoover for pointing out these features of British banking in Thornton’s day.

↩ -

2

Princeton University Press, 2009; see my review in these pages, May 28, 2009.

↩ -

3

There are, however, valid concerns about how to implement the Volcker Rule and what some of its effects would be; see, for example, Hal S. Scott, Testimony before the US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, February 4, 2010.

↩