Bill McKibben’s new book is a passionate appeal from a writer who has dedicated his efforts to warning of the risks posed by human-driven climate change. It describes the challenges we face—whether from effects on the environment that are already occurring, or from those that will occur due to the greenhouse gases we have already emitted and are likely to emit in the coming decades—if we do not act to curb emissions. But while McKibben insists on the importance of strong action to reduce those risks, he struggles to find grounds for optimism and often tilts toward a pessimism that has characterized recent works by other environmentalists, such as James Lovelock.

The title, Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet, sums up McKibben’s main theme: we have now altered the climate to such an extent that the planet as we knew it no longer exists, and it should have a new name, Eaarth. The idea that we should find a way of acknowledging the fundamental impact that humans have had on the earth is not new. Paul Crutzen, who shared the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1995 for showing how chlorofluorocarbons, then common in aerosols, caused the hole in the ozone layer, suggested ten years ago that the current geological epoch should be called the “anthropocene” in order to “emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology.”

In 2007, McKibben launched “350 .org,” a group that advocates the need to stabilize concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at 350 parts per million, and thus stay as close as we can to the levels occurring over the last few thousand years during which we created our civilizations. That is compared with the preindustrialization concentration of about 280 parts per million. The trouble is that the current concentration is about 385 parts per million, according to the US government’s Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center. And when other greenhouse gases, such as methane, are taken into account, the overall level is about 435 parts per million of carbon-dioxide-equivalent. For this reason, many of the policies for controlling climate change that have been proposed so far focus on stabilization at 450 parts per million of carbon-dioxide- equivalent as being the best we can do to limit the great risks from climate change.

We are likely to exceed that level within the next decade but, with strong action, concentrations of greenhouse gases could peak in this decade and, over a long period of time with continued strong action, return to 450 parts per million or below. But if we carry on with something like “business as usual,” we may reach concentrations by the end of the century that would imply a significant chance, perhaps as high as 50 percent, of a rise in global temperature of 5˚C or more above its level in the nineteenth century. This would be a temperature that has not been seen on the planet for more than 30 million years (Homo sapiens has been here for only around 200,000 years). The map of where people could live would probably be radically redrawn. This could imply, for example, that some areas would become deserts, some would be inundated, and many subject to radical change in weather patterns or in the location and flows of rivers. This could mean in turn the movement of hundreds of millions or billions of people. History suggests that movements of people on such a scale would likely involve extended, severe, and global conflicts.

McKibben explains that his conclusion about climate change draws on a presentation by the distinguished NASA scientist James Hansen at a scientific conference in December 2007 in which he claimed that 350 parts per million should be the upper limit for atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, and that we have already passed a level that could be described as “safe.” With not much immediate prospect for returning below 350, McKibben’s book is an attempt to outline how our lives must change because “the earth that we knew—the only earth that we ever knew—is gone.”

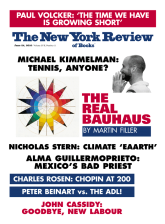

This Issue

June 24, 2010