In August 1955, in the middle of his annual summer sojourn on the Italian island of Ischia, W.H. Auden received from Dr. Enid Starkie, the distinguished author of books on Baudelaire and Rimbaud and a lecturer in modern languages at the University of Oxford, a letter inviting him to stand as a candidate for the Oxford Professorship of Poetry. This five-year post was about to be vacated by Cecil Day-Lewis, the back legs of that mythical beast McSpaunday (Louis MacNeice, Stephen Spender, Auden, Day-Lewis), which had rampaged through the British poetical and political circles of the 1930s, warning the old gang that their time was up, threatening mayhem, revolution, bloodshed: “Don’t bluster, Bimbo,” Day Lewis had, not entirely convincingly, threatened, “it won’t do you any good;/We can be much ruder and we’re learning to shoot.”

It was Auden’s evasion of the task of shooting at, or at least playing a part in the fight against, Nazi Germany that initially gave him pause for thought. His and Christopher Isherwood’s decision to settle in America in 1939 had been widely denounced in Britain. Their detractors included Harold Nicolson—who, by a neat twist of fate, would prove to be Auden’s principal opponent in the battle for the Oxford professorship—and Evelyn Waugh, in whose Put Out More Flags two lily-livered left-wing writers, Parsnip and Pimpernell, abscond to America the moment war breaks out. Indeed Auden and Isherwood’s dereliction of national duty was even discussed in Parliament, where Sir Jocelyn Lucas asked, in June 1940, if they might be summoned back and enlisted.

In his reply to Starkie, Auden cautiously pointed out that he was now an American citizen, which was likely to prove a “fatal handicap” in the election; and further, that as the post paid only £300 a year and required long periods of residence in England, it would severely straiten his circumstances. His main source of income during this period was literary journalism for publications such as The New Yorker and The New York Times, temporary academic appointments, and poetry tours like that commemorated in “On the Circuit” of 1963:

Another morning comes: I see,

Dwindling below me on the plane,

The roofs of one more audience

I shall not see again.God bless the lot of them, although

I don’t remember which was which:

God bless the U.S.A., so large,

So friendly, and so rich.

Starkie, however, was undeterred. Unlike many in the Oxford humanities faculties, she fervently believed that the Oxford Professor of Poetry should be a practicing poet rather than a literary critic. In Auden she felt she’d found a fitting successor to Day-Lewis. She wrote again, and then again to Ischia, and Auden eventually capitulated. She at once undertook to organize his campaign, since it was deemed—and still is—unmannerly for the candidates to promote their own cause with any vigor (as Ruth Padel recently found to her cost).

The results were declared on February 9, 1956: Auden polled 216 votes, Nicolson 192, and the Shakespeare scholar G. Wilson Knight 91. (Since only those with an Oxford MA were allowed to vote, and votes had to be cast in person, turnout in this era was always pretty low. Waugh, unimpressed by the two “homosexual socialists,” commented caustically in his diary: “I wish I had taken my degree so that I might vote for Knight.”)

Accordingly, in June 1956 Auden returned to Oxford University, where he’d achieved only a third-class degree, but where his first book of poems had been published twenty-eight years earlier in an edition of “about 45 copies,” printed up on a hand press purchased by Stephen Spender for £7. The composition of his inaugural lecture, which was entitled “Making, Knowing and Judging,” seems to have caused him acute anxiety; while working on it, he confessed to Spender in a letter of May 8, he was periodically overcome by “fits of real blind sweating panic.” “Why,” he asked his old friend, “are the English so terrifying?”

The question revealingly signals the ambivalent nature of his relationship at this point with his country of birth. It’s worth remembering how very much the poetry of the early Auden, starting with those poems printed by Spender back in 1928, derived their energies and imagery from a desire to figure “the condition of England”:

Go home, now, stranger, proud of your young stock,

Stranger, turn back again, frustrate and vexed:

This land, cut off, will not communicate….

These lines from “The Watershed,” written while he was still an undergraduate, perfectly capture the tensions that would beset this “stranger” at last returning to his “stock” in 1956, seventeen years after leaving them, and how nervous and unsure he felt about what lines of communication would now be open between them. In a canny move he decided to end this first lecture by reading a poem by the most English of English writers, and the one, as he often said, who’d had the most influence on his own early development: without the poetry of Thomas Hardy, he noted, before reciting Hardy’s wonderful self-elegy “Afterwards,” “I should not now be here.” As Edward Mendelson points out in his introduction to this newest volume of Auden’s collected prose, if the audience had refused to applaud when their new Professor of Poetry then sat down, they would seem to be snubbing Hardy as well as Auden.

Advertisement

If Hardy was the most inventive and varied prosodist in the history of English poetry, Auden runs him a close second. On the other hand, Hardy’s poetry can’t really be said to illustrate the ringing affirmation with which Auden concludes the main text of this first lecture:

Whatever its actual content and overt interest, every poem is rooted in imaginative awe…. There is only one thing that all poetry must do; it must praise all it can for being and for happening.

Should hymns to the creation be what you’re after, then Hardy is surely not your man. And I think the term “imaginative awe” only makes sense in relation to the poetry of Hardy, and that of the early or English Auden too, if we strip the term of any notion of rapture and think of it as describing a position of radical detachment, allowing all to be surveyed as if from the summit of Wessex Heights, or, in Auden’s phrase, “as the hawk sees it or the helmeted airman.”

It was the clinical authority with which Auden diagnosed the ills besetting his country in what might be called Britain’s first post-imperial decade, the 1930s, that led so many to figure him as a kind of national prophet of doom. The effect on his contemporaries can perhaps best be summed up by a couple of lines by the poet Charles Madge (who would later cofound the social research organization Mass Observation): “There waited for me in the summer morning/Auden, fiercely, I read, shuddered and knew.” The impish William Empson, however, couldn’t help poking a little fun at the spectacle of all these ex–public schoolboys collectively reveling in forthcoming apocalypse:

Waiting for the end, boys, waiting for the end.

What is there to be or do?

What’s become of me or you?

Are we kind or are we true?

Sitting two and two, boys, waiting for the end.

(“Just a Smack at Auden”)

It was at least partly to escape from the role of court poet to the British left, a role actively assumed in poems such as “Spain, 1937” but also one to an extent thrust upon him, that Auden moved to America, though the principal reason he always gave for his emigration was that he fell in love with Chester Kallman in the course of a trip to New York in 1939.

He also, though, justified his decision to settle there permanently in relation to his poetic ideals and development. In a letter of January 16, 1940, Auden explained to the classical scholar E.R. Dodds that America would allow him to attempt to live “deliberately without roots”; “America may break one completely,” he added, “but the best of which one is capable is more likely to be drawn out of one here than anywhere else.” His aim, in other words, was to become, if such a thing is possible, a post-national poet. The atavistic conflicts at that moment destroying Europe led him to espouse the belief that responsible poetry must free itself from all tribal affiliations; the poet’s task, therefore, was to map possible ways of living in an existential void, in the “age of anxiety,” to borrow the title of his long poem of 1947.

The Age of Anxiety* is set in a bar in New York, and its four characters, Malin, Rosetta, Quant, and Emble, are allegorical representations of the four Jungian categories of Thinking, Feeling, Intuition, and Sensation. A bar, Auden explains in the poem’s prologue, is “an unprejudiced space in which nothing particular ever happens,” which is what makes it the perfect setting for a dispassionate study of the search for meaning that deracinated, alienated modern man must undertake.

And yet, despite his conviction that by leaving England he had freed himself from parochial concerns, from the dangers of nationalist fervor, and from his own family romance, and thereby made himself into a truly international and contemporary poet, a bit of Auden seems still to have hankered after the approval of the old gang. What else could explain his willingness to heed Dr. Starkie’s call in the summer of 1955? The dread inspired by the thought of returning to Oxford, Mendelson notes in his introduction, “unsettled his whole sense of himself and his career.”

Advertisement

This dread found its fullest poetic expression in a poem entitled “There Will Be No Peace,” which “was an attempt,” Auden later revealed to the American critic Monroe K. Spears, “to describe a very unpleasant dark-night-of-the-soul sort of experience which for several months in 1956 attacked me.” Auden pictures himself confronting serried ranks of nameless enemies, “Beings of unknown number and gender”; all he knows is that they do not like him:

What have you done to them?

Nothing? Nothing is not an answer:

You will come to believe—how can you help it?—

That you did, you did do something;

You will find yourself wishing you could make them laugh,

You will long for their friendship.

There will be no peace.

Fight back, then, with such courage as you have

And every unchivalrous dodge you know of,

Clear in your conscience on this:

Their cause, if they had one, is nothing to them now;

They hate for hate’s sake.

As far as the response to his inaugural lecture went, he needn’t have worried. The day after, he victoriously declared in a letter to Kallman: “Never in my life have I been so terrified, but thanks to Santa Restituta, I had a triumph and won over my enemies.”

But his use of the term “enemies” and the unsettling paranoia of “There Will Be No Peace” suggest that his return to his alma mater activated, in Mendelson’s words, a “sense of dread at an imaginary threat [that] was stronger than any he had felt at any real one.” Certainly Auden was no favorite of the dominant British critic of the 1950s, F.R. Leavis, whose influential magazine Scrutiny routinely attacked him as “adolescent” or “immature”—code words for gay. There would never be peace between Auden and Leavis. Probably more troubling for him was the defection of young British poets such as Thom Gunn or Philip Larkin, who saw the American Auden as more of a lost leader than an emotionally arrested deviant.

In a Spectator review of Auden’s 1960 collection Homage to Clio, Larkin imagined a conversation between someone who had read only the later American Auden and someone who had read only the pre-1940 English Auden: a “mystifying gap,” he suggested,

would open between them, as one spoke of a tremendously exciting English social poet full of energetic unliterary knock-about and unique lucidity of phrase, and the other of an engaging, bookish, American talent, too verbose to be memorable and too intellectual to be moving. And not only would they differ about his poetic character: there would be a sharp division of opinion about his poetic stature.

“What’s Become of Wystan?” was the title of Larkin’s review, which, though written more in sorrow than in anger, must have wounded deeply. It is an impressive testimony to Auden’s refusal to engage in literary tit-for-tat that when, a few months later, he was asked to review the American edition of Larkin’s The Less Deceived, he gave the volume an unambiguous thumbs up.

Auden’s stint as Oxford Professor of Poetry lasted from 1956 to 1960. After the first year, to cut down on travel, he was permitted to give his stipulated three lectures per year over a few weeks in early summer, rather than one in each of the three academic terms. He also let it be known that he would be available for conversation with young poets from three o’clock every afternoon in the Cadena coffee shop, where he was approached by, among others, the young Gregory Corso, who tried to kiss the hem of his trousers. Auden’s advice to all poetic ephebes—advice that can’t have made much impression on the free-spirited Corso—was invariably “Learn everything there is to know about metre.”

Versions of most of his Oxford lectures were included in his first large-scale collection of criticism, The Dyer’s Hand (1962), which takes up about half of this volume of Auden’s prose, number IV in the series, expertly edited and annotated—as always—by his executor Edward Mendelson. Auden borrowed the title for The Dyer’s Hand from Shakepeare’s sonnet 111, in which the poet presents himself apologizing to his beloved for the fact that his lowly birth has forced him to seek his fortune, and make his name, in the public sphere:

Thence comes it that my name receives a brand,

And almost thence my nature is subdued

To what it works in, like the dyer’s hand.

In Auden’s case the apology seems to be to poetry itself, to which his commitment might seem diluted by his willingness to turn his hand to the critical prose he had to write to earn a living.

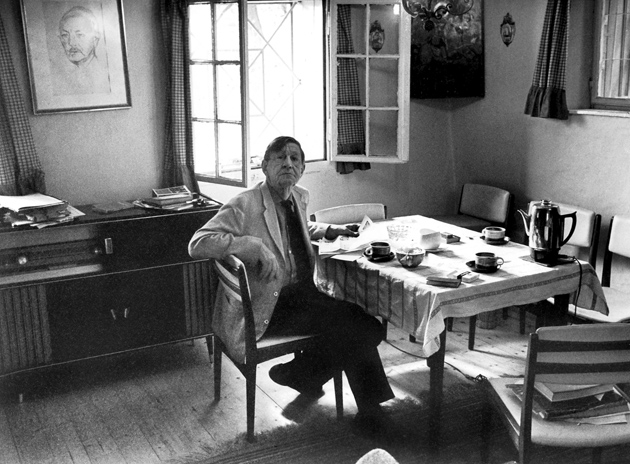

Auden’s productivity throughout his working life in both poetry and prose was really quite astonishing, but particularly so during his American years. He treated himself almost like a machine, observing a rigid work schedule and fueling himself with Benzedrine, which probably contributed to the way his face so dramatically cragged up in his mid-fifties. He had not only himself to support, but Kallman too. Fortunately, he was never short of an opinion, and seems to have been able to churn out review copy relatively painlessly, but a doorstopper such as this volume has one gasping again at his sheer industry, at the steely will and powers of concentration that enabled him to fulfill the huge number of tasks that editors offered him, and that he accepted in order to subsidize the writing of his poetry in the summer months.

Auden’s prose, like his poetry, insistently reveals his compulsion to seek certainties. In World Within World Stephen Spender suggested that “Auden’s life was devoted to an intellectual effort to analyse, explain and dominate his circumstances”; this effort, it seems to me, can be traced in nearly all of his writings. From the outset a didactic, or spoof-didactic, rhetoric permeates his modes of address. While his father was a doctor, both his grandfathers were clergymen, and surely the imaginative force of many of his most powerful early poems derives from the pulpit-like authority with which they deliver gnomic warnings or issue urgent instructions. Although we may not be sure on what grounds his judgments are made, we watch in awe as he decisively separates the sheep from the goats: “It is time for the destruction of error,” he sternly counsels in a poem written when he was only twenty-two:

The falling leaves know it, the children,

At play on the fuming alkali-tip

Or by the flooded football ground, know it—

This is the dragon’s day, the devourer’s….

This is from the poem, later called “1929,” that calls for the “death of the old gang,” who are to be “forgotten in the spring,/The hard bitch and the riding-master,/Stiff underground.” Against them he poises a mythical young male redeemer-figure: “deep in clear lake/The lolling bridegroom, beautiful, there.”

In later life his need to “dominate his circumstances” drove him to develop various elaborate systems of classification. In many of the pieces collected here divisions and subdivisions proliferate. This can occasionally make for a somewhat dry reading experience for those not in thrall to the urge to categorize—here is a typical extract from an essay called “The Virgin & the Dynamo” included in The Dyer’s Hand:

Since all human experience is that of conscious persons, man’s realization that the World of the Dynamo exists in which events happen of themselves and cannot be prevented by anyone’s art, came later than his realization that the World of the Virgin exists. Freedom is an immediate datum of consciousness. Necessity is not.

The Two Chimerical Worlds

(1) The magical polytheistic nature created by the aesthetic illusion which would regard the world of masses as if it were a world of faces. The aesthetic religion says prayers to the Dynamo.

(2) The mechanized history created by the scientific illusion which would regard the world of faces as if it were a world of masses. The scientific religion treats the Virgin as a statistic. “Scientific” politics is animism stood on its head.

More than once, reading these essays, I was put in mind of Samuel Beckett’s parody of philosophical academic discourse in Lucky’s great speech in Waiting for Godot. This compulsion to classify reaches its apogee in an elaborate table that Auden includes in an introduction to Romeo and Juliet, which offers the reader four headings: “Character,” “Wrong Choice,” “Consequence,” and “Right Choice”:

Character: The Apothecary.

Wrong Choice: Sells poison to Romeo.

Consequence: Romeo’s temptation to suicide is strengthened by his possession of the means.

Right Choice: He should have obeyed the law and refused to sell Romeo the poison.

Character: Romeo.

Wrong Choice: Kills himself.

Consequence: He is damned.

Right Choice: Even if Juliet had really been dead, he should, at whatever cost of suffering, have remained alive and true to her memory.

Character: Juliet.

Wrong Choice: Kills herself.

Consequence: She is damned.

Right Choice: She should have remained alive and true to Romeo’s memory.

The final verdict that Auden delivers in this essay on the lovers’ suicides struck me as somewhat harsh: “To kill oneself for love is, perhaps, the noblest act of vanity, but vanity it is, death for the sake of making una bella figura.” In a piece on Othello he reveals himself similarly unimpressed by the love of the tragedy’s principals; he dismisses Desdemona as “a silly schoolgirl” and tells us that he shares Iago’s doubts “as to the durability of the marriage” she has entered into. Surely both Romeo and Juliet and Othello become rather pointless when perceived from such angles; if we don’t feel something valuable and unique has been destroyed when Shakespeare’s lovers come to grief, haven’t we been wasting our time?

Such judgments reflect the stern, anti-Romantic side of Auden, and indeed, as Mendelson argues in his introduction, notions of responsibility and guilt dominate his critical prose in this era. He responded enthusiastically to Edmund Wilson’s Apologies to the Iroquois (1960), lambasting the “cultural conceit” that allowed the white man to believe that “any individual or society that does not share our cultural habits is morally and mentally deficient—it makes no difference if the habit in question is monogamy or a liking for ice cream.” While the most outrageous of the crimes committed against the original inhabitants of America may be in the past, the “cultural conceit,” Auden argues, remains.

As well as The Dyer’s Hand, this volume contains almost one hundred miscellaneous pieces—reviews, radio talks, forewords to the Yale Younger Poets Series that he edited (choices from this period included James Wright, William Dickey, and John Hollander), essays he wrote for the two book clubs he worked on with Jacques Barzun and Lionel Trilling, and introductions to various anthologies such as A Treasure Chest of Tales: A Collection of Great Stories for Children and The Viking Book of Aphorisms (coedited with Louis Kronenberger). One gets Auden’s take on a vast range of writers: Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, Sydney Smith, D.H. Lawrence, Dostoevsky, Ibsen, Cavafy (one of the best pieces), Ronald Firbank (another good one), Byron, Dag Hammarskjöld, Faulkner, Marianne Moore, Robert Frost, Robert Graves, Charles Williams, Martin Luther, Henry Treece, and Stendhal—and artists such as Van Gogh and Leonardo da Vinci, and composers such as Beethoven, Berlioz, Mozart, Stravinsky, and Rossini. All these—and many, many more—find their respective niches in the great many-branched Auden schema.

In the process one learns a great deal about all sorts of things, but one also reads a lot of sentences that begin “There are three kinds of…” I confess I found it something of a relief to turn from this encyclopedic tome to the ludic, genial, avuncular world of his poems from this period, with their twinkle-eyed mix of the arcane and the demotic: “Steatopygous [large-buttocked], sow-dugged,” begins “Dame Kind,” a ripely camp address to Nature, to whom Auden then snuggles up as if he were back in the nursery—“She mayn’t be all She might be but/She is our Mum.” The year after his accession to the Oxford Professorship of Poetry he was awarded the Antonio Feltrinelli Foundation Prize, which was worth over $33,000. He used a portion of this unexpected windfall to purchase a small farmhouse in Kirchstetten, a village about half an hour by car from Vienna, close enough to go to the opera. This signaled the end of his summers in Ischia, a move commemorated in “Good-Bye to the Mezzogiorno,” a poem that typifies the deft, conversational mode that was the later Auden’s ideal:

Out of a gothic North, the pallid children

Of a potato, beer-or-whisky

Guilt culture, we behave like our fathers and come

Southward into a sunburnt otherwhereOf vineyards, baroque, la bella figura,

To these feminine townships where men

Are males, and siblings untrained in a ruthless

Verbal in-fighting as it is taughtIn Protestant rectories upon drizzling

Sunday afternoons….

It’s a style he developed most brilliantly in the early “Letter to Lord Byron,” and while his later deployments of it tend to lack the sprezzatura of that masterpiece, it yet generates many skillful, amusing poems, and is put to particularly effective use in the sequence “Thanksgiving for a Habitat,” begun in the spring of 1962. Given the fact he was one of the most famous poets on the planet, and at a time when the prestige of poetry was much higher than it is now (Time magazine planned to run a cover story on him in 1963, backing out only when the managing editor found out he was gay), it is touching to find him amazed at the turn of fortune that has granted him his own “bailiwick,” and at last luxuriating in the security of home-ownership:

what I dared not hope or fight for

is, in my fifties, mine, a toft-and-croft

where I needn’t, ever, be at home tothose I am not at home with….

Many of the poems of this period celebrate friendships; each of the rooms in “Thanksgiving for a Habitat” is dedicated to a particular friend or couple: Isherwood gets the toilet (“this white-tiled cabin/Arabs call The House where/Everybody goes“); Kallman the living room, where he and Auden are comfortably pictured at work on British crossword puzzles under the benign regards of Strauss and Stravinsky; and MacNeice, who had died in 1963 (a year before this section was finished), the study, or “Cave of Making’. Ensconsed in this room where “neither lovers nor/ maids are welcome,” Auden sits at his Olivetti portable, dictionaries (“the very/best money can buy”) at hand, turning “silence” into “objects”; and in the crafting of these objects, however low their poetic pressure, his pride is undimmed, for “even a limerick,” he declares,

ought to be something a man of

honor, awaiting death from cancer or a firing-squad,

could read without contempt.

-

*

A new edition of this poem, edited and with an introduction by Alan Jacobs, was recently published by Princeton University Press. ↩