In the run-up to the violence last year around the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, a woman named Erika, who is active in the white supremacist group Identity Evropa, was busy posting on Discord, an app originally used by gamers but used at that time by some on the far right. She helped organize transportation and housing for the rally. And after Airbnb cancelled the bookings of known white supremacists, she scrambled and found them, via a different rental site, a spacious house outside the city center.

Her terms for agreeing to an interview with me and photography were that we use only her first name, though it’s not hard to find evidence of her racist activism, online and offline. Identity Evropa has targeted college campuses where its pro-white agenda is visible through banner drops, flyer pasting, and the promotion of an “identitarian” politics that advocates for the oxymoronic concept of a peaceful ethnostate. That Saturday night, on the day that Heather Heyer was killed and many were injured, Erika hosted a party where IE and the other far-right activists could celebrate their “victory.”

It was early evening, but already a handful of women and about a hundred men, many khaki-clad, had gathered—drinking heavily and eating pizza. In a bedroom upstairs away from the party, I interviewed Erika and another Identity Evropa member, and took their portraits. During the second interview, the “alt-right” activist Richard Spencer, who was meeting privately with IE leaders in the bedroom next door, started yelling maniacally about “kikes” and World War II. Several times, I heard him shout: “I rule this world!”

Spencer was then at the peak of his power, before several failed rallies, domestic violence charges, and a high-profile divorce tarnished his reputation. But like his predecessor David Duke, the former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan and Louisiana state representative, these slick ambassadors of white power seem to live many lives and somehow find reincarnation in a new tailored suit.

Around 9 PM, members of the League of the South, the Traditionalist Worker Party, and other white supremacist groups started pulling up to the house. A drunken man asked me, point blank, why Jews shouldn’t be gassed as I stood on the edge of an enclosed porch next to him, Spencer, and a few other men. His friend insisted that he was a good guy, just a little worked up. I left the party.

This week, James Fields, the white supremacist who drove a car into a crowd and killed Heather Heyer and injured others, was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. But for the wider question of culpability for that day’s violence, for the massive uptick in hate crimes in America, for the perpetuation of systemic racism generation to generation, embedded in our families and our institutions—we need more complicated answers.

It is a universal truth that women’s work is seldom recognized. But failing to acknowledge women’s part in sustaining white supremacy is not just sexist; it’s a dangerous mistake. For every media report about a white male terrorist who is portrayed as a “lone wolf” or a “madman,” there are untold stories about the women who provide support for, nurture, and connect these groups and individuals.

In 2017, I began exploring the topic of women who participate in extremist politics and hate groups because, like many East Coast liberals, I was surprised by the number of white women who had voted for Trump. I wanted to meet not just regular women who supported him, but women at the extreme end of the political spectrum. As I pursued the project, I wanted to understand why anyone—especially women—would embrace white supremacy.

Over more than a year, I met nearly two dozen women, from Manhattan to Montana: white supremacists and nationalists, conservative extremists, the “alt-right,” militia members, conspiracy mongers, Twitter personalities, so-called sovereign citizens, racists, haters, xenophobes, and Nazis. Some were well known; others not.

Lauren Southern is perhaps the most popular female figure on the far right. A media personality with a Twitter following of nearly 400,000, Southern made a film about “white genocide” in South Africa, a conspiracy theory that was picked up by Tucker Carlson on Fox News and led President Trump to tweet about the subject. I also met activists who were elected officials, such as Theresa Manzella, a member of the Montana House of Representatives, who told me that she had to act before Sharia law takes over and establishes no-go zones in her state—like the ones there were already in Michigan, she believed.

Advertisement

Then there were the others like Elaine Willman, a mid-level player in the Montana pro-white activist scene who claims she simply cares about “water rights” but is widely considered anti-American Indian; she told me that we’d already paid the Native Americans for their land once. Or KrisAnne Hall, who, on her perpetual speaking tour, told lawmakers and citizens in the Michigan Capitol building in Lansing (at the invitation of a gun club) that they are not obliged to follow any laws made by the federal government.

While I was working on this project, I learned to conceal my shock and fear. To get the work done, I deflected the rare questions about me, and said, truthfully, that while I didn’t agree with them, I was interested in learning more about their ideas and why they believed these things. Many assumed I was there to show them in a “positive light,” and were thrilled I had called them up and wanted to interview and photograph them—though this was not always the case. Some people declined to meet me, and early in my reporting, I was ejected from a conference of a neo-Confederate hate group and forcefully escorted out by armed men. The night before the violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, I drove through the dark woods to a remote cottage without cellphone service and was “tested” by a group of neo-Nazis by being given a piece of pizza with bacon.

But mostly I met with people individually—though many of these women insisted that their husbands be present. When women brought their children, as a rule, I did not photograph them. In one case, though, a woman who is a one-star brigadier in a splinter cell of the Three Percenters militia group (so called because they see themselves as the successors of the “only” 3 percent of American colonists who, they believe, took up arms against the British) insisted that I photograph her eight-year-old daughter, to whom she has given the nom de guerre “Smiley,” because she is the “future of the movement.”

“The Movement.” I heard a lot about The Movement.

Online, Ayla Stewart goes by the handle “Wife with a Purpose.” Her Instagram posts are mainly about homemaking and baby-making, but she also includes praise for “Trad” German and European culture, and she sells things in her Etsy shop like a drawing called “American patriarchy,” of a mustachioed man with a gun in front of an American flag.

The day we met in a public park in the southeastern United States, through an introduction from Spencer, one of her sons told me he was very excited to have his picture taken because he had a new haircut: short on the sides, long on the top—“fashy,” one might even say. It was a Wednesday afternoon, just five days after Heyer was killed in Charlottesville.

Stewart’s posts on Gab, a no-holds-barred “free speech” platform, are frequently about such subjects as black crime, Silicon Valley’s enabling pedophilia, Muslim crime, the Proud Boys, Holodomor (Stalin’s 1930s terror-famine in Ukraine). She’s also issued a “white baby challenge” with the explicit goal “To End ‘Black Ghetto Culture.’” But, she insists, she isn’t racist. “There are many Black, Latino, Jewish, Asian, American Indian, etc. women who follow me and participate in the trad life hashtag and meme, some are even my best friends,” she wrote me in an email.

Stewart doesn’t need to be openly racist to get her message across. To her, racism means what she calls the “standard classical” definition of judging people “by the color of their skin”; because she believes that she has no personal malice toward African Americans or other minorities, it is therefore impossible and insulting to imply that she is racist. This allows no room for structural racism, internalized power relations, historical disenfranchisement, or nuance. Anyone who calls her a racist is using the wrong definition. Nazism, on the other hand, has three definitions, which she can elaborate with ease: people who are ironically trolling, people who believe in some form of Holocaust revisionism or denial, and then people who are “legitimate” Nazis. These, she argues, are few and far between.

Stewart hates it when people in The Movement use swastikas. Not because she hates swastikas, but because, in her words, displaying them is “unproductive.” Using the same exasperated tone to try to get her youngest child to stop eating the woodchips on the ground of the play area where we chatted, she exclaimed, “Just, yeah, don’t do it!”

Advertisement

Her online presence is carefully curated to separate a white supremacist aesthetic from the more blatant politics of white supremacy. She had more than 30,000 Twitter followers before her account was deleted, and is a darling of various groups on the far right who share in the lifestyle fantasy of homemaking and raising white children.

Offline, she talked openly about being a part of The Movement. The Movement is as hard to define as its membership is to quantify. Ideologies and member rosters are fluid and overlapping, with attempts at deflection and differentiation among groups as a deliberate strategy to avoid detection. Those who seek to show strength inflate their numbers; those who seek to play down being more than just a Traditional Mama with an online following will try to conceal their ties.

Being part of The Movement is about protecting your family and future from perceived enemies—that is, blacks, immigrants, Jews, feminists, liberals, and a federal government that wants to take away your guns and force you to embrace multiculturalism. Parsing the rhetoric of racial separatism, anti-Semitism, anti-feminism, and anti-government activism reveals shared touchstones: to fight for “white rights” is always a fight against minorities. To fight against the government is to reject laws protecting civil rights. To fight for a “traditional lifestyle” is to fight for a return to a time when those laws did not exist. To fight for “land rights” is to insist that indigenous peoples’ claims to the land are not valid. To fight for “white children” is to follow in the footsteps of the coalitions of white mothers in the 1960s who resisted mandatory school integration.

In February, I met Matthew Heimbach at a Denny’s in French Lick, Indiana. He wore a T-shirt featuring Oswald Mosley, a British fascist leader of the pre-war period, and ordered a giant omelet. Heimbach is one of the most prominent young leaders of neo-Nazis in America, though he prefers to say that he’s a National Socialist. Before I got there, he told me that I couldn’t meet his wife, Brooke. (Earlier this year, he was arrested on a charge of assaulting her, and another woman in their group, in an alleged domestic violence incident.) But once we met, he changed his mind. After breakfast, we headed to their house in nearby Paoli.

Brooke, baby-faced and sweet, welcomed me kindly to her home. She had a clear conversion narrative. Like many white nationalists, her path to living with a Nazi began at home. Her stepfather made a racist podcast that she used to listen to, and when she was nineteen, he let her accompany him to a conference held annually by American Renaissance, a group led by Jared Taylor that promotes eugenics and other racist theories. She worked at a book stall, where Heimbach purchased a book inspired by Mussolini’s regime. He asked for her phone number, which she wrote in the book.

“There is no way to separate what seems like women’s benign actions and what we see as hate at crimes,” Kathleen Belew, a historian of white supremacy and the author of Bring the War Home, told me. “Without women, they [the men] could not have done so much violence.” And without women’s providing the social glue for The Movement, Heimbach would have neither the personal capital that helps forge links to other groups, nor the veneer of “family values” and legitimacy that Brooke gives him.

The day after I met Ayla Stewart, I drove to North Carolina blasting the Ramones’ “The KKK Took My Baby Away” on my rental car stereo. The next stop on this roadtrip of hate was to meet Chris and Amanda Barker, the Grand Dragon and Imperial Kommander, respectively, of the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Chris may be the Grand Dragon, but it’s Kommander Amanda who gets much of the work done: sewing robes in her spare time, hanging with the klanswomen in the kitchen, baking hams before the rally. Ladies’ Auxiliary units maintain contacts, mail coupons, and send baby baskets year-round—because life is too busy to set crosses on fire every weekend. Amanda spoke of her Klan Family because it’s white women who have always kept the Klan together—from its heyday in the 1920s to the present.

“Women’s suffrage was the catalyst that brought women across the political spectrum together, but once their initial goal was achieved, any sense of unity went out the window,” Vegas Tenold, the author of Everything You Love Will Burn, a book about the recent uptick of white supremacism in America, told me. “White, Protestant women who had discovered their political voice during the suffragette movement now decided to use that voice to maintain white hegemony.” And while the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed white women the right to vote, this wasn’t something black women secured until the 1960s.

To be in the Klan is to believe that you live in an unfair world where you’ve been deprived of what’s rightfully yours and everyone is your enemy except these people who wear the same robes and the same secret Klan words. These people are your friends. When they all dress up together, they perform rituals that make them feel important, remind them of their membership and of their enemies, who are lurking everywhere except for the group encircled around that burning cross. They call their rallies “Lightings,” not burnings. While they’re intended to inspire terror, they’re also opportunities for family picnics.

Several months after our meeting, in August 2017, Amanda sent me an email inviting me to an “Imperial Klonvocation,” offering me journalist access for a $500 fee. She urged me to book soon—“Media slots will be going fast.” I replied that it was a violation of journalistic ethics for me to pay for access. They offered a discount rate, but I never went. After all, I thought, a burning cross picture is a burning cross picture: there are plenty of such images in historical archives and this is how they want to be seen—terrifying, anonymous, powerful.

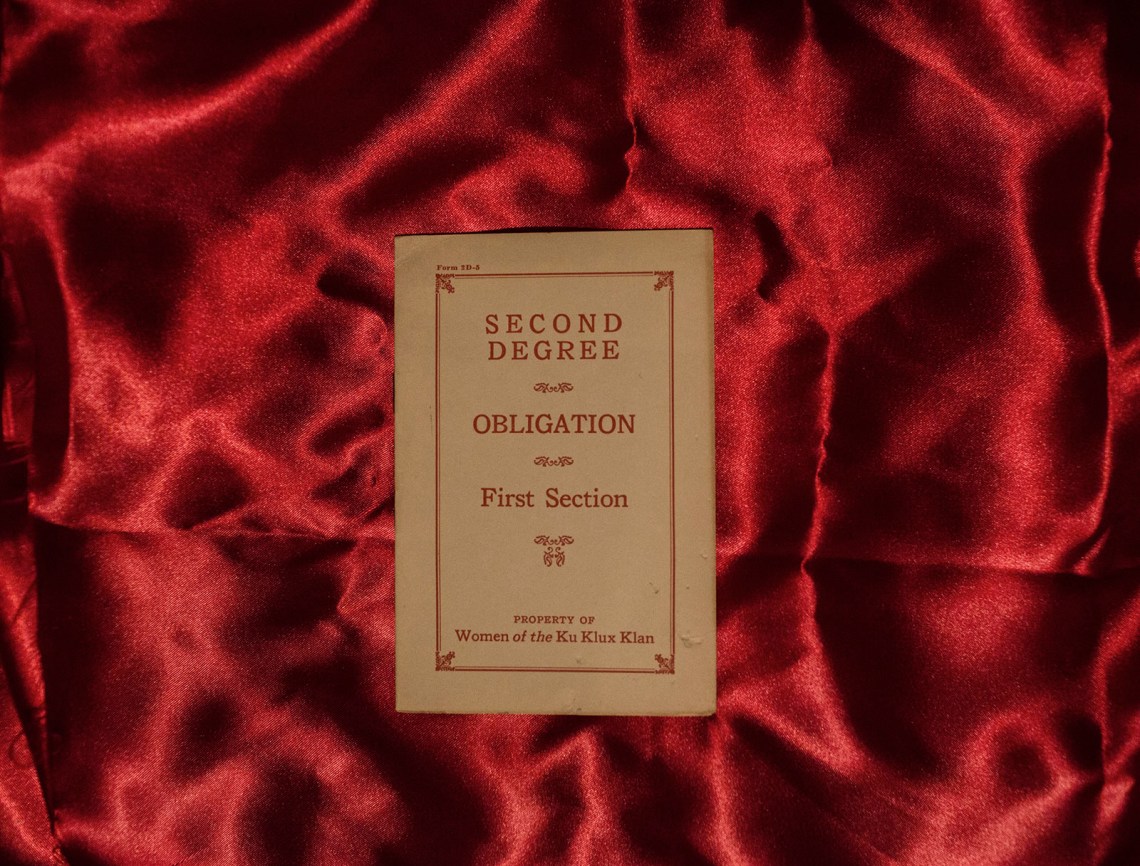

The reality of Klan living—on a back road in Pelham County, North Carolina, without cell phone service—was neither grand nor imperial. In their shabby living room, months earlier, Amanda had showed me artifacts from a chest filled with antique Klan paraphernalia. The Barkers were broke and planning to auction stuff on eBay.

One Saturday morning in April, which is officially Confederate history month, I drove to a cemetery in Raymond, just outside of Jackson, Mississippi, to meet members of the Order of Confederate Rose, which describes itself as a Southern heritage society. There in the cemetery, a half-dozen women, accompanied by men wearing Confederate soldiers’ uniforms, had dressed up as “Black Roses”—in mourning gear of black hoop skirts, veils, and hats—to lay wreaths on some graves.

Afterward, at lunch, when I tried to push them to acknowledge that they were dressing up as slave owners, they dodged the issue. They insisted that people dress up as Union soldiers, too. When I pointed out that no one dresses up as slaves, one of them said that she wished they would. Another member, a leader of their chapter of the Order, is a public school teacher. She’s not racist either, she said; after all, she has black friends. There have been problems for her at her school when Facebook posts about her Rose activities emerged, but that has nothing to do with the group’s politics, she insists, just problems at her school.

“It’s not that I want to forget [slavery],” another member Tara Bradley told me. “It’s not that I try to pretend it didn’t happen. I don’t. It happened, and there’s nothing we can do about it.” Bradley said that only 5 percent of Southerners owned slaves. In fact, in Mississippi in 1860, nearly half of families did.

Bradley brought her twelve-year-old daughter to the cemetery and to lunch. She’s not old enough to formally join the group yet, so she’s still a “Rosebud.”

For some groups within The Movement, racism is the primary reason for their existence: they believe in myths about persecuted whites, and that genocide and race war are imminent. For others, racism underscores their actions, and is implicit but secondary to their activism. And for women in The Movement, many find meaning in providing the wombs upon which the collective future of the white race depends. Some are maternal archetypes for all the men who didn’t come home from school to milk and cookies; others are beautiful plastic Aryans peddling an illusion of availability.

Women like Amanda and Erika also do the grunt work of pro-white activism. And women like Tara and Ayla follow the time-honored tradition of bringing up racist children—that #trad lifestyle they admire so much that once included taking the family out for a day’s entertainment at public lynchings. These women present outsiders with an “acceptable face” of white supremacy, a soft, palatable point of entry with the nostalgic glow of an idealized, wishfully apolitical past. This attempt to neutralize the stigma of more overt racism makes women of The Movement valuable recruiting tools, far more insidious than skinhead thugs or robed Klansmen. To understand the radicalization of white supremacy in the United States, we need to comprehend its roots as a complex, extensive ecosystem with unexpected hubs of power.

In the aftermath of the violence at Charlottesville, many said, “This isn’t America!” But this is precisely America: from slavery to segregation, the violent reinforcement of hierarchies through lynchings to Jim Crow, mass incarceration to police brutality, nothing is more American than racism. It is built into our institutions and psyches. And nothing ensures the survival of white supremacy like denying white supremacy. This isn’t just about extremists and those whose symbols are more legible as white supremacy: this is about the way America is built on the foundation of white supremacy, and the way those at the farthest ends of the spectrum influence the middle.

It is difficult to look at the painful reality that we share this country with racist extremists. Many argue that we shouldn’t cover the far right, that it gives them oxygen and that we are better-off depriving them of a platform. The problem is they already have a platform—their own—and they aren’t going away. We must look critically at these groups and who holds power and how their ideas enter the mainstream. It’s not just about their performative hoods, but who the people in the robes are, and who is signaling more quietly but just as dangerously.

Much has been said and written about the “toxic masculinity” of the far right and white supremacy, but on the other side is a toxic femininity just as invested in the idea of a whiteness as victimized, at risk, and requiring protection. Not all extremists are equally racist or equally dangerous, but everyone I spoke to contributes to that exclusionary and poisonous discourse. For some I met, their de facto membership in The Movement is a fundamental way of life, an identity, and a set of core beliefs through which everything is filtered. For others, it’s a phase, like joining a sorority during college, cosplay for racists, but with far more menacing consequences.

Fringe extremists like the ultra-violent group Atomwaffen pose a grave risk to public safety, but they are not the ones changing our nation. Women like Ayla Stewart are doing that, one white baby and one white follower at a time.

Glenna Gordon

Many groups on the far right insist that they are not Nazis and do not publicly use swastikas. Privately, the symbols are rampant. Image provided by the leader of the women’s faction within a group largely involved in organizing the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, 2017, who has since left The Movement

Reporting for this story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and the New School Faculty Research Fund.

An earlier version of this article misstated the location of French Lick; the town is in Indiana, not Illinois. The essay has been updated.