This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our e-mail newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

The British painter and art historian Julian Bell is a longtime contributor to The New York Review of Books. In our May 9, 2024, issue—the Art Issue—he writes about the American painter Nicole Eisenman’s first major museum exhibition, which surveys nearly four decades of work and which traveled from London to Munich before landing stateside, where it will be up through September at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. “Her force of mind, both aesthetic and political, is magnetic,” Bell writes, “although all I know of history tells me that even now, a young artist will somewhere be plotting a pushback against her warmhearted humanism.”

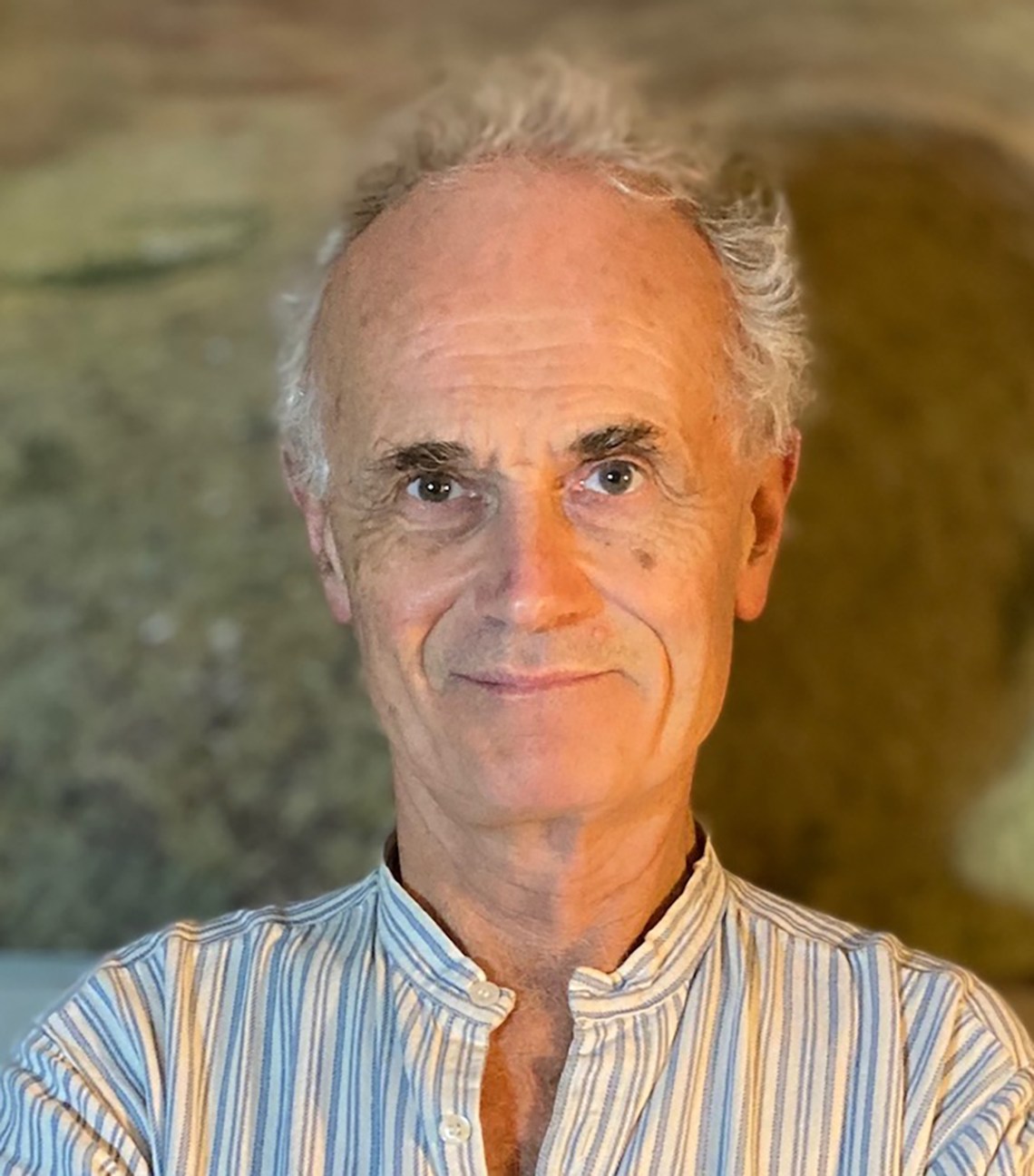

A living painter is an unusual subject for Bell, who has written for the Review about, among many other artists, Francis Bacon, Vermeer, Goya, Poussin, and, most recently, Rubens. He is the author of six books about art. The latest, Natural Light—which was excerpted in our pages—is a study of the early-seventeenth-century painter Adam Elsheimer, known for his Flight into Egypt (1609), painted just a year before he died at the age of thirty-two.

Bell wrote me this week from Lewes, England.

Sam Needleman: You begin to account for Nicole Eisenman’s style by remarking that, across her work, the hour is late: “Time to shut it, boy. Time running out for orders to the bar, time running out for the US to change course…. The less tomorrow becomes thinkable, the more license to splurge today.” Which painters does this aspect of Eisenman’s work recall?

Julian Bell: A hunch that there’s a civilizational crisis has spurred many a painter—not just the German Expressionists and Philip Guston, people Eisenman clearly looks to, but the likes of Francis Bacon, who averred that with the ebbing of faith “all art” had “become completely a game,” and that all the twentieth-century artist could do was“deepen the game.” More generally, painters love to scratch away at “latecomer” status like a favorite itch—think of Degas sighing that one can no longer paint like Ingres. The hunch doesn’t necessarily work wonders for the quality of the paintings, but it might make them more publicly discussable. The hunch’s recurrence from one generation to the next doesn’t necessarily render it suspect. Right now, it really is late. Agonizingly late.

Of Eisenman’s painting Seder (2010), in which she depicts her family around the Passover table, you write, “Her edges interlock with such panache…. We see the youngest child at table gleefully plunge her knife into a beet-topped gefilte fish that’s refracted through a wineglass: what a joy of invention, both comical and formal, has gone into that collision of incidents.” Is it usually in such details that you find the joy of invention, or do you more often find it in the bigger picture?

I wander around galleries with a sketchbook, and I just let things grab me. That Seder detail was one beauty that I hit upon in the Eisenman show—another, for instance, was the interweave of hands and faces where a guy is seen helping his partner light a cigarette in The Abolitionists in the Park (2020–2022). Eisenman excels at these witty figural knots. Her compositional strategies, however, are mostly unremarkable, hand-me-down stuff. With another painter it might be the overall address to an expanse that has me reaching for my pencil—the way, say, that Julie Mehretu swoops down on surfaces with her forebodingmurmurations.

You write for the Review about old masters far more frequently than new ones. What is it about Eisenman’s work, as opposed to that of other living painters, that compelled you to go contemporary?

I’m an exhibiting artist, and it doesn’t do to diss my living colleagues, so I only draft criticism of them if there’s plenty to admire, or if they inhabit lofty reputational plateaus to which my sallies could never ascend. I have found the era from 1590 to 1670 particularly thrilling to write about, because so much about “nature”—about what the world constitutes—seemed at stake for painters then. But my overall reason to write is that I am temperamentally curious. I don’t have any programmatic agenda for art, merely a hope to cut through received patterns of thought—that, and a human-to-human nosiness about the various outcomes of the widespread impulse to make something to look at. Eisenman’s bold, ambitious figural practice offers an occasion to wonder about what’s happening now, in the 2020s. As a fellow figure painter, I hope I’m qualified to comment.

As a fellow figure painter, do you cheer the good standing of your genre in the twenty-first century?

In the 1990s, when I started writing about art, my own type of practice had to push upstream against surges of “death of painting” effluent. Now the current’s reversed. And there could be a temptation to play the disappointed agitator (“Ach, I didn’t mean that kind of revolution!”), but no—a smarter role would be Ecclesiastes. As long as there are rooms with solid walls and people who are inquisitive and people who have money, an economic niche for flattish handmade objects to hang on those walls remains a probability. Whether those items are figurative or not seems to me incidental: what matters more is their address to the whole body of the person making or viewing them, rather than purely to the eyes and fingertips of the person engaged digitally.

Advertisement

Will you tell me a bit about life in Lewes?

I work in a converted cowshed just outside Lewes, a small town fifty miles due south of London. Lewes is known for its Norman castle, its brewery, and its pyromaniacal devotion to Bonfire Night—November 5. The shed and the town beyond contain many makers and friends who are up for a good conversation. It’s a lucky place in the world to be!

In addition to writing, you have long painted. What are you working on now? And if it is even possible, might you describe the relationship between your painting and your writing?

I start the day writing, continue it painting—at least, when the plan goes right! I’ve just finished a big panorama of Dover, where you touch down on this island if you come from mainland Europe. It’s meant for a solo show of journey paintings due to open next March in London, probably to be entitled “Roads.” Words tend to give up on me by noon, and I don’t feel they’re the main drivers to the paintings. Yet parallel impulses operate. In either practice, it seems to me there are great riches of space out there, and it’s my job to make a place—a compact, resilient schema—through which they can be apprehended. So you could say that in that sense, I remain fixated on nature.