I never considered my grandfather to be a danger to the republic, but J. Edgar Hoover disagreed. When I knew my grandfather, he was in his late sixties, lived on Fifth Avenue, and did not seem very interested in world revolution or overthrowing the US government. But Hoover never ordered the tap removed from my grandfather’s phone, because, as his biographer summarized the FBI view, Grandpa never stopped being “a dangerous radical out to destabilize race relations in the United States.”

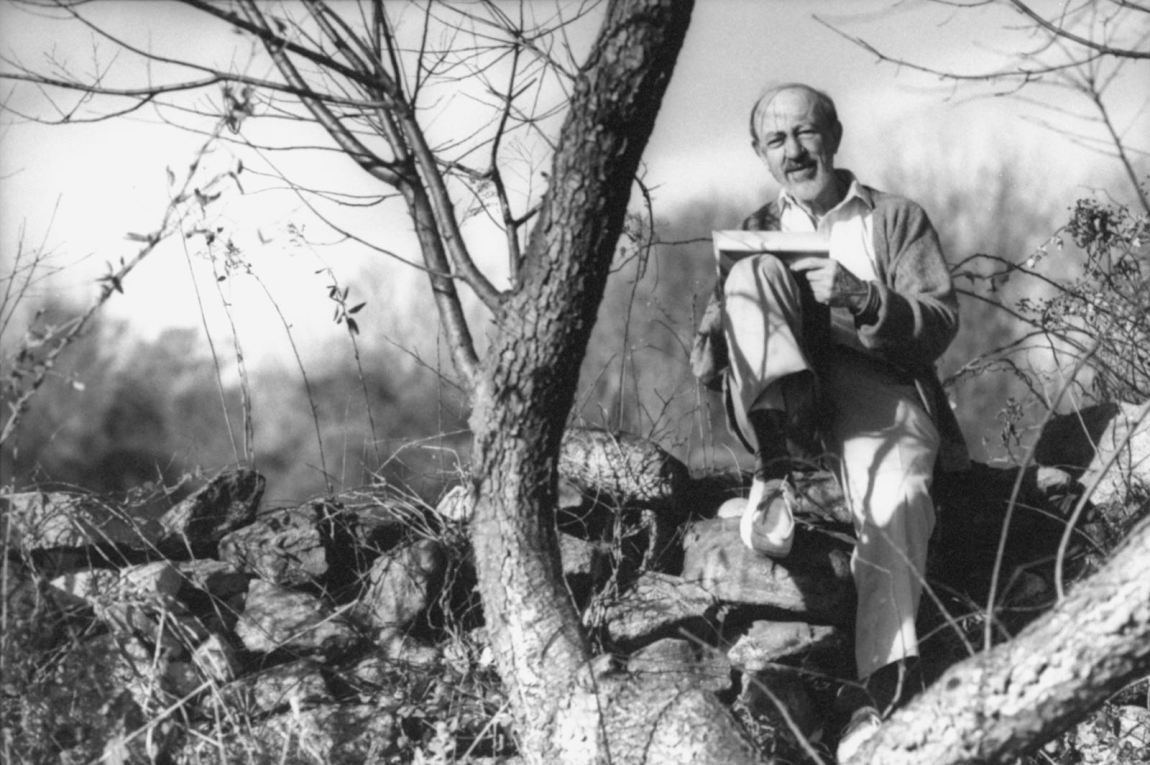

To me, Howard Fast simply looked like a million other cranky old Jewish guys from the tristate area. He could have been an aging allergist from Westchester or a retired bus driver from Queens. He wore a shearling coat in the winter months and a wool cap on his bald head. He enjoyed taking the Madison Avenue bus and eating in diners. He did the crossword. Sometimes, he took me to his club, which occupied an old McKim, Mead, & White Renaissance revival building on West 43rd. It was filled with other elderly men.

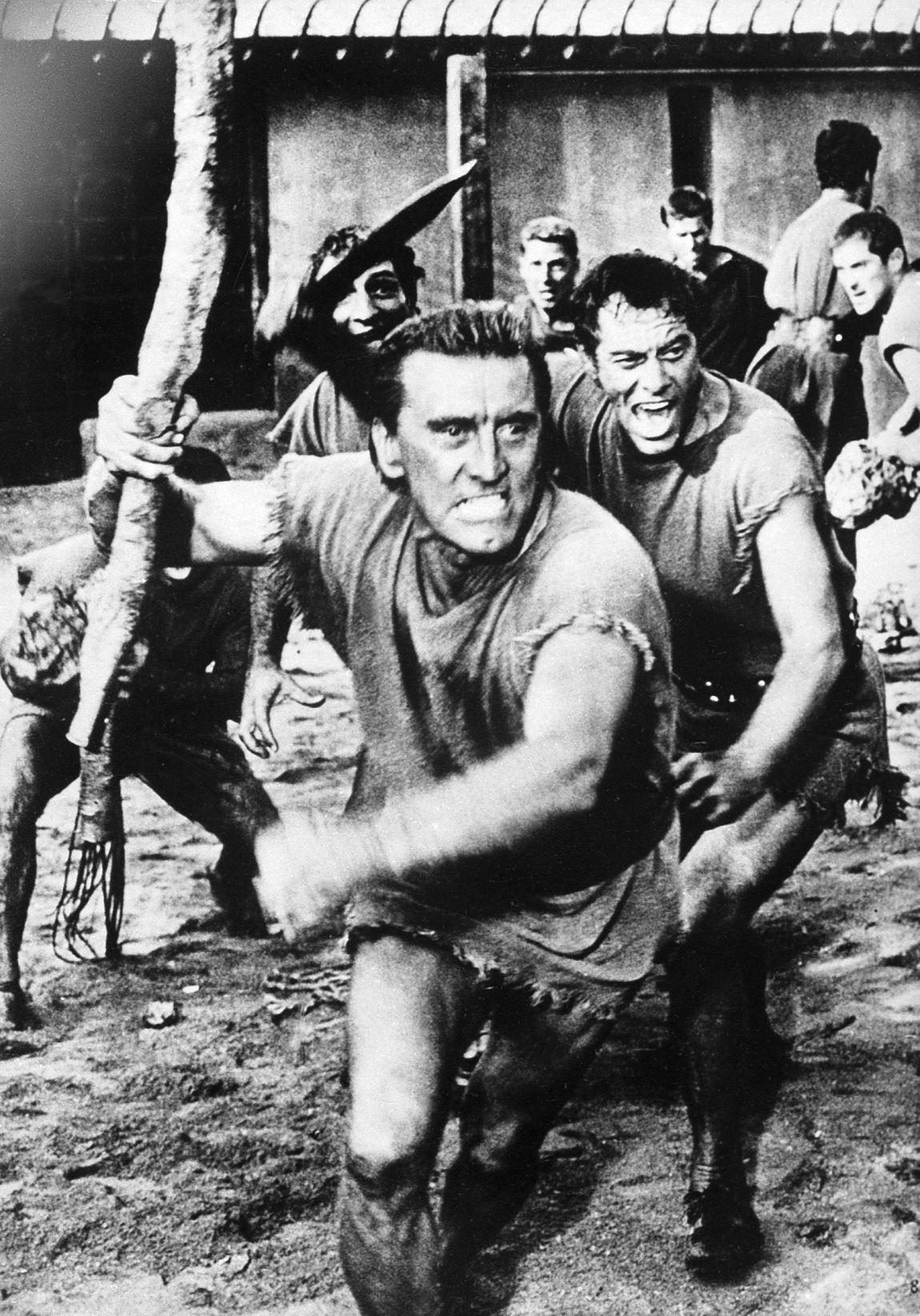

My grandpa didn’t seem like much of a radical to me. Sure, he had opinions. Enormous opinions about almost everything. He hated Kirk Douglas, for instance, really hated him—even though Douglas had starred in the movie adaptation of Grandpa’s novel that made him famous, Spartacus. But to be outshone by a mere actor…that was unforgivable.

The only clue to my grandfather’s former affiliation as a Communist was that he was convinced that The New York Times was somehow against him because it was dominated by Trotskyists (it wasn’t). So what was Grandpa’s dangerous subversive activity? As he later told the Times—notwithstanding his suspicion of its infiltration by Trotskyists—in 2000:

I was in federal prison in West Virginia for three months [in 1950] for contempt of Congress for refusing to comply with a request of a congressional committee of Congress, the House Un-American Activities Committee. After the Spanish Civil War against Franco, a group of us got together a [second] group of well-to-do people who were sympathetic to the lost cause of a Republican state. We bought a convent in Toulouse and converted it into a hospital run by the Unitarians. It took care of the Spanish refugees who fled to Toulouse. There were many thousands of them and their families. We were asked to give the donors’ names and refused. All twelve of us were sent to jail.

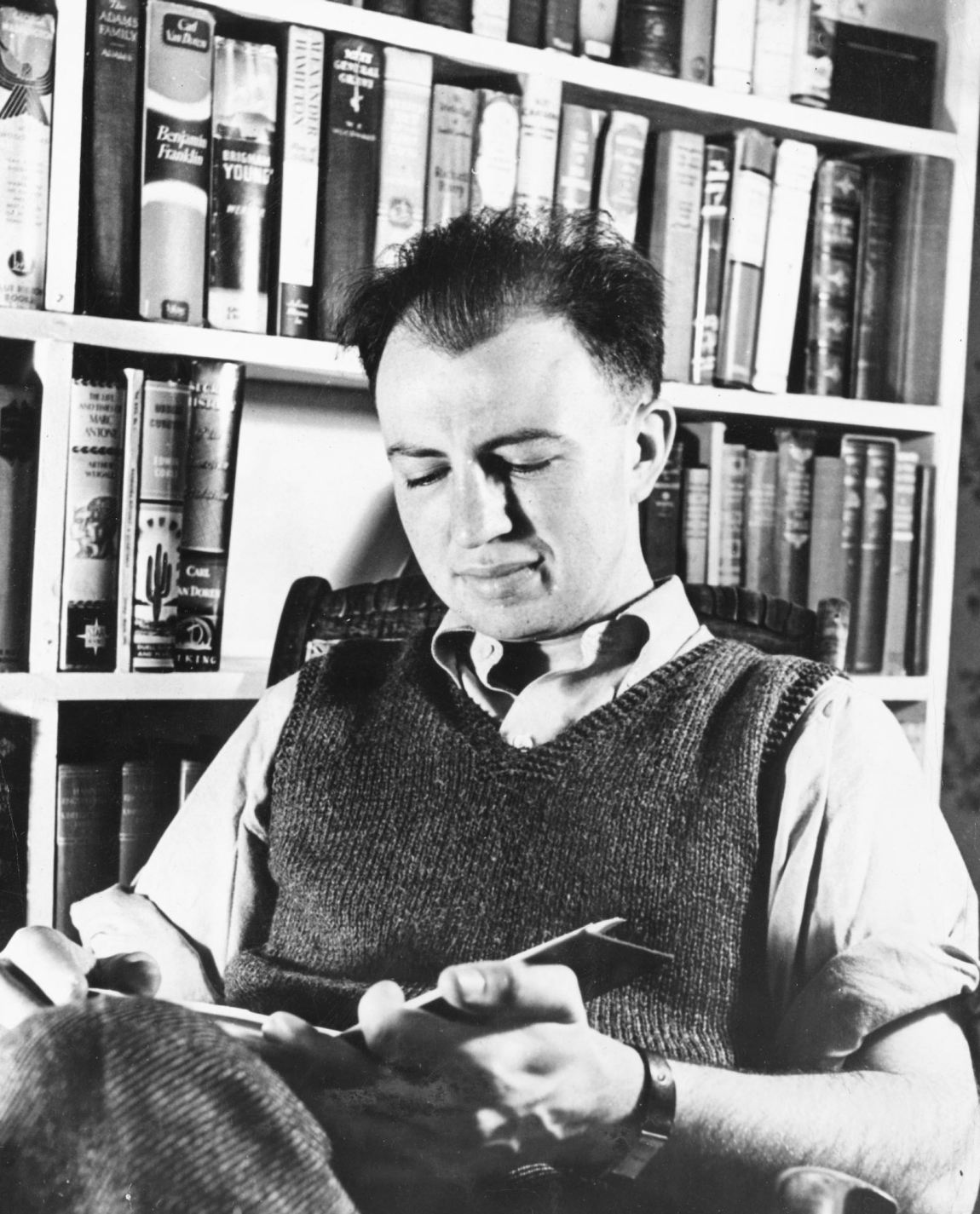

His crime was silence, an unwillingness to play ball with the House allies of Joseph McCarthy, the anti-Communist, witch-hunting senator. Grandfather plead the Fifth, vehemently, and was held in contempt of Congress. But Grandpa hadn’t always been an enemy of the state. In fact, just a few years before he was jailed by the US government, he had been loyally working for it, writing propaganda for the Office of War Information at the American news service the Voice of America—in effect, selling World War II to the American people. Of course, for someone like my grandfather, a Jew of that generation, World War II was very different from any war before or since—serving in this one, against the Nazis, they very much considered their patriotic duty.

But what I knew, growing up, of my grandfather was neither his patriotism nor his radicalism, but the ways he profoundly disappointed those around him. My grandfather was a bad father to my father, mean and punitive. A serial adulterer, he was also a bad husband to my grandmother. His philandering wasn’t one of those family secrets locked away, as it might have been in a normal family; no, it appears brazenly, in the very first chapter of his autobiography, Being Red. One thing I will say for the writers in my family: they always wanted to give the reader the dirt. Unfortunately, the dirt was always us.

And what of the dirt J. Edgar Hoover had on my grandfather? I was eleven when I stumbled on Grandpa’s FBI file, among the cardboard boxes full of papers that lined the sideboard in my grandparents’ dining room. There were papers everywhere. I picked up one of the pages. It was just black lines, lots of black lines; almost all the words were blacked out. Someone had sat in a room in Virginia with a marker pen because knowledge of those words supposedly still represented a threat to national security—long after Hoover’s G-men had filed their original reports.

Grandpa has now been dead almost eighteen years, so his silence is a given. But somewhere on the FBI’s computer servers in Virginia, there’s an unredacted version of the file that defined him as an “enemy of the state.” His Times obituary put it this way: “Mr. Fast joined the [Communist] party in 1943, a decision he often said was made at least in part because of the poverty he experienced as a child growing up in Upper Manhattan.” All very virtuous, or at least well-intentioned. But I wasn’t so sure—I’d read other accounts, heard different stories. I called my dad to ask him about how Grandpa got involved in communism.

Advertisement

“Any explanation of your grandfather usually involves a woman who isn’t your grandmother, you know. And he had this affair with the woman who married that pumpkin microfilm Richard Nixon guy.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Just Google: pumpkin, Richard Nixon, microfilm.”

I did, and the results I got were all about Alger Hiss. I got back on the phone with my dad.

“Grandpa had an affair with the woman who would marry Alger Hiss?”

“Sure,” my dad said. Hiss, an alarmingly charming WASP, was a senior State Department official who was accused, in 1948, of spying for the USSR. (He always proclaimed his innocence but was subsequently convicted on a related perjury charge. He later retired to the Hamptons, wrote his memoirs, and became a dedicated birder.)

Grandpa’s dalliance was not something I’d learned reading between the black lines in his FBI file. Had Hoover’s men fallen down on the job? Arguably so, because the character who appears in the feds’ account is almost unrecognizable—as my grandfather himself acknowledged in his autobiography:

The eleven hundred pages detailed every—or almost every—decent act I had performed in my life. If I were to seek some testament to leave to my grandchildren, proving that I had not lived a worthless existence but had done my best to help and nourish the poor and oppressed, I could not do better than to leave them this FBI report. In those pages, there is no crime, no breaking of the law, no report of an evil act, an un-American act, an indecent act—and I was no paragon of virtue, and I did enough that I regret—but the lousy bits and pieces of my life are nowhere in those pages, only the decent and positive acts: speaking at meetings for housing, for trade unionism, for better government, for libertarianism, for a free press, for the right to assemble, for higher minimum wages, for equal justice for black and white, against lynching, against the creation of an underclass, against injustice wherever injustice was found, and for peace, and walking picket lines, and collecting signatures. These are what make up that brainless report.

In the years since my grandfather died, I have become more involved in politics myself, and gotten to know some First Amendment and civil rights lawyers. One of them helped me use the Freedom of Information Act to get a copy of “that brainless report.” When it came, it was via email—the report’s reams of pages in PDF format. It seemed much less scored-through with black marker than I’d remembered from my girlhood.

As I was looking over it all, I got a message from a former FBI official I’d met through my work. “When looking through your grandpa’s FBI file,” he wrote me in a message, “check the margins; sometimes Hoover would write on them directly.” Hoover, of course, had a notorious nose for vice: after failing to destroy Martin Luther King Jr. as a Communist stooge, he set about snooping on King’s philandering. Had he noted down my grandfather’s dirty secrets, too?

There were scribbles in the margins, but they were impossible to read, the ink faded and smudged by time. And I wondered whether, just maybe, I had been letting my grandfather’s vice obscure his virtue.