“People evangelize because they fear that the belief to which they have committed themselves may not be true.” T.M. Luhrmann has spent many years doing fieldwork as an anthropologist studying faith communities, and her insights into the experience of American charismatic Christianity are slightly sad. These are people who believe that God speaks to them directly; it is easy to think of them as being full of certainty, perhaps even grandiosity. What Luhrmann describes, however, is a more fretful relationship with the divine. The evangelicals she interviewed worked hard to keep God salient and present in their lives:

They said again and again that God’s power and love were infinite, but they often felt helpless and unlovable; they often said that they forgot to pray for help when they should have prayed; and they often struggled with apparently unanswered prayers. They talked about the mystery of faith, and how little they understood of…why God allowed such pain in their lives.

So it goes without saying that you do not temper someone’s religious zeal by calling them stupid—they know that they are fallible and mortal and sometimes wrongheaded: they are sinners, after all. “Devout modern Christians talk constantly about not being faithful enough,” writes Luhrmann. This is a community familiar with making an effort, with working hard in the face of the unknowable, which makes you wonder if the effort—that twist of worthlessness in the gut—is not intrinsic to believing in anything that is not provably there.

Luhrmann speaks to people of different faiths in many cultures. She does not ask what they believe so much as how they experience belief; this is not a book about theologies. Luhrmann’s methods are phenomenological, deliberately small. She records and does not question how people describe themselves. Some of the time they describe themselves as slightly embarrassed about their deeply personal relationship with God. They do not describe themselves as authoritarian, moralizing, or misogynistic, but why would they? The question Luhrmann asks is not just how religion is socially constructed, but how it becomes personally vivid: What is the spark that makes a shared God not just real, but so present he talks back to you?

For American evangelicals, the problem of God is endlessly a problem of the self. In the Horizon Christian Fellowship in Southern California, people spoke of intense personal difficulty, of self-destruction and despair followed by redemption. They told of “a wild ride through drugs, sex, alcohol, and depravity until they hit bottom,” at which point they finally turned to Jesus and were saved. The addiction narrative is so common that Luhrmann wonders if it affords an alarming glimpse into American, or at least Californian, life, but it might also be asked whether feelings of transcendence require a knowledge of abjection: you cannot be found if you already know where you are.

Luhrmann wryly notes that, for these believers, God seems to be a member of the National Rifle Association. The narrative of sin is so powerfully one of substance abuse that right-wing Christians think of welfare as wrong because it forms “dependency.” According to Betsy, an erstwhile hippie and born-again Republican in Orange County, welfare has created “monsters.” Betsy, we must assume, depends entirely on God, but only in a good way.

American evangelicals speak to God about their feelings, and they do this because they assume their feelings matter. In the Western tradition, according to Luhrmann, the mind is imagined “as a private place, walled off from the world, a citadel in which thoughts are one’s own and no one else has access to them.” Nor can these thoughts leak out to act directly on the world; they cannot, for example, make another person ill or better. For American evangelicals, God is mostly about them. He is a friend, and, like a friend, he helps solve everyday problems—dilemmas about relationships, personal happiness, and the choices people make in life: “You can ask him what shirt you should wear and what shampoo to buy.”

Evangelicals in other cultures experience God differently, though the practice of their imported Pentecostalism is very much the same. In Chennai, India, where personal feelings are not privileged over family values, people are more likely to experience God “in their human father and through other people.” In Accra, Ghana, where prayers against demons are commonplace, God’s voice is experienced viscerally, often as an exhortation, and he is also expected to enact revenges and punishments in the world. Both Indians and Ghanaians are happy to discuss things that might be felt in some “spirit sense” that is hard to name. Most Ghanaian evangelicals hear God’s voice audibly, which is to say, in the room.

Advertisement

For Americans, the mind is separate from the world. In order to make it available to supernatural experience, they must occupy a mental space these other cultures take for granted, which Luhrmann calls “the in-between.” Believers cultivate a talent for “absorption,” an immersive focus that blurs the boundary between inner and outer experience. This is “the mental capacity common to trance, hypnosis, dissociation, and perhaps imagination itself.”

Of all the evangelicals Luhrmann interviewed, the Americans were the only ones to call themselves crazy, albeit in a slightly jaunty way (“Hm, okay, that sounded odd”), when describing how God speaks to them, which he does personally and all the time. He does so through circumstance, coincidence, and especially scripture. When they hear his voice it is not exactly audible, though a third say they have heard him “in a way they could hear with their ears.” Many said that random thoughts came into their heads and they knew these came from God because they were unexpected and felt so right. They do know the difference between literal and spiritual experience and are not psychotic. About 30 percent experienced the physical cataplexy of being “slain in the spirit,” or the adrenalizing delight of being filled with the Holy Ghost. These, along with lesser moments of conviction, were followed by feelings of “peace, intense joy, sudden sleepiness.” Who would not want to be visited in this way, to feel the mystical dissolution of the self? “It was just all one and it was all consuming, captivating, fulfilled, utter bliss, all joy, no tears, just beauty beyond anything you could ever know on earth.”

The people I like best in Luhrmann’s account are the ones who hear nothing, but wait patiently nonetheless. Evangelicals do not know why some “become gifted practitioners of their faith and others with the intention and desire to do so struggle and do not.” This form of bemusement reminds me of people who “can’t” write fiction, though they read novels and enthusiastically attend readings. They speak of fiction-making not just as something technically difficult but as something both tantalizing and impossible.

I was born again when I was sixteen, which was over forty years ago. My memory of the group yearning I sensed in a suburban living room in South Dublin will always be fond as well as embarrassed. This was not a punitive space. It also managed, for the few months I attended prayer meetings there, to be somehow asexual. I remember the self-blaming confessional monologue that Luhrmann describes and that often stands for public prayer, but in my group there was also an amount of bliss enacted on an average rainy Tuesday as people, including me, entered a kind of minor trance that was close to dissociation, but with none of the dull terror of that state. It was happy—as advertised—and filled with light.

At sixteen, every choice felt huge and worthy of God’s great attention. It was also a time when the world tilted toward the uncanny: I “saw” ghosts, “understood” evil, and imagined myself, for some of the time, pretty much like the teenagers in those American horror movies in which heavy petting unleashes telekinetic powers. And though my sense of supernatural possibilities arrived with adolescence (astral traveling was my idea of a night out, at the age of twelve), it did not entirely disappear in adulthood, though I felt, perhaps, that it should.

I seldom tell people about my early religious episode. It feels almost like a secret. But I might have made a talented believer, I think, and still experience the occasional “vision.” I think of them as a harmless form of psychic debris. Some are experienced as properly external, but most happen in Luhrmann’s “in-between” space, what you might call the mind’s eye, or in the proprioceptive sense I have of my body’s boundaries. I have felt the touch of a person I loved, after death, at an entirely unexpected time. I do not believe in ghosts, however, or I don’t care about believing in ghosts. I am a fiction writer. I am fully content in the mental space where the imagined becomes meaningful. This is where I spend my day.

The difference between the novelist and the woman at prayer is that the novelist knows, more or less, that the voices she generates come from herself, though some, famously, take on a life of their own, leading to the strange questions asked of writers about their relationship to their characters. These can seem redundant, when properly considered: How do you have a relationship with something that is not autonomous? But actually human beings can have a “relationship” with anything. The works of Mozart. Their hair. My mother once said she had a very good relationship with a certain brand of washing machine. Some people say they have a relationship with themselves—so what do you know? Given such propensities, the question might not be how people relate to God, but how they can stop themselves. How do they manage to still the affective hum of the world?

Advertisement

As any parent laboring over a bedtime story knows, children can be quite literal-minded (indeed some of them never grow out of it). The very young are keenly aware of the difference between reality and make-believe, no matter what their culture. In 1930 Margaret Mead, in New Guinea, observed that children gave her disinterested stares when asked about magic and spirits; it was the adults who spent hours talking about ghosts. The tug and play of belief takes some social encouragement, and it does not always take a “spooky” form. Not all American believers interviewed by Luhrmann are trying to conjure a sense of presence. At a shul in San Diego for Jews who had recently become Orthodox, the word people used most often was “connection.” They felt connected “to an imagined community that included not only all Jews living, but all Jews stretching back generation upon generation.” At Christ the King, a Catholic church in San Diego with a special emphasis on Black culture, the Mass was a drama of transubstantiation in which the congregants became participants. They also had a different sense of narrative circumference from that of the Horizon Christian Fellowship: “Rather than God entering their story, they entered God’s.”

The first sparks of shared belief come from stories, and the power of the story, for Luhrmann, comes from its use of physical detail, the more concrete the better. The reader of the Gospels is “captured by the realness of the metaphor without losing sight of its figurative nature.” It is good to have a place to start out from, but this tethering of belief to the real seems a little narrow, considering how quickly it moves away from the real, and how far it can get. It might also work in the other direction: our feelings of presence, or of immanence, might exist before we find the words to shape and share them. Some religions use language that is altogether incomprehensible to the listener, or even to the speaker—whether Church Latin or the Pentecostal “speaking in tongues.” The experience of listening or producing such sounds can be intense, for being both infantile and elevated, but it is not made so by our comprehension.

There is at the heart of prayer a sense of beautiful impossibility, and this plays out in all the paradoxes and rules that we invent, either to elaborate the pleasures of belief or to control belief’s helplessness. Raised a Catholic, I know, for example, about original sin, the Immaculate Conception, and the spirituo-sexual Möbius loop that facilitated the virgin birth of Christ. I also know how to secure a Sabbatine privilege, whereby you are allowed into heaven on the first Saturday after death, no matter what day of the week you die. It can be hard to admire the simple quality of faith, when it is kept that way by limitless rules and complication.

And yet, the theological dance can be so nice. Eliot Weinberger’s Angels and Saints is glorious, in the literal sense of the word, for its discussion of those incorporeal beings, the angels. There are only two hundred of them in the Bible, but they proliferated in later texts and they are, today, more popular perhaps than God. Google lists 1,970,000,000 Web pages on which the word “angel” appears. Modern angels are babies, guardians, warriors, and financial investors. They are the better angels so often invoked on Capitol Hill. A staple of iconography from Raphael to Hollywood, they allow religion to cut loose and have a bit of fun.

In the Bible, they are warriors: they exile, wrestle, smite, and bring plague. One appears with “a face like lightning,” others are entertained unawares, very few have wings. Much effort has gone into the counting of angels. The Talmud says there is one for every blade of grass, but how, being incorporeal, could they be counted at all? The arguments wind through Augustine, Aquinas, and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, who wrote The Celestial Hierarchy around the year 500 (inventing the word “hierarchy” for that purpose). The division into thrones, dominions, virtues, powers, and principalities comes from a line in Colossians. The idea of a guardian angel comes from the Psalms. The cherubim start out as “the storm winds that carry [God] on his throne,” or they are four-footed animals, or later, according to Aquinas, they are those heavenly creatures who know things and who therefore can fall (demons are, by comparison with angels, always very intelligent). Richard of St. Victor wrote, in the twelfth century, that cherubim lead the soul into “secret places of divine incomprehensibility.”

Such was the authority claimed by mystical analysis of the Bible that the arguments feel almost scientific. It took Martin Luther to call Pseudo-Dionysius out entirely, when he wrote, “Is not everything in [The Celestial Hierarchy] his own fancy and very much like a dream?”

These days, angels are tamer than they used to be. Pope John XXIII talked of sending his guardian angel to argue with the guardian angel of someone with whom he did not agree, and this story feels both homespun and sentimental when compared with the whirling wheels full of eyes seen by Ezekiel, or the ecstatic angelic vision of Teresa of Ávila. “In his hands,” she writes,

I saw a golden spear, with an iron tip at the end that appeared to be on fire. He plunged it into my heart several times, all the way to my entrails. When he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out, as well, leaving me all on fire with love for God.

“If we saw an angel clearly,” said Birgitta of Sweden, “we should die of pleasure.”

Angels often appear to ecstatic virgins, both male and female, who are in a high state of penitential degradation. Although they inspire awe, a sense of presence can be hard to catch. They do not feel interior in the way that God can sometimes be experienced in the heart. Angels are “out there” and tend toward the visual in our imagination. They look human but share godlike qualities, and this hybrid nature leaves them in a permanent state of contradiction. Aeviternal, because created, they exist between eternity and temporality. They have “no individual personalities” and yet are always full of joy.

The questions these beings inspire might be about the nature of abstraction itself. They are also about the body—what it is to occupy one as opposed to look like one. Do angels have senses? (Can they smell? If not, why do they have noses?) Can they remember events, or read human minds? How do they move? Sadly, Weinberger does not list my own favorite question, which is why they are represented as having navels, even though they were not of woman born. Also, if they have no gender, then why are all their names male, as is plaintively asked on the Internet by people demanding equal rights for the beautiful and unreal.

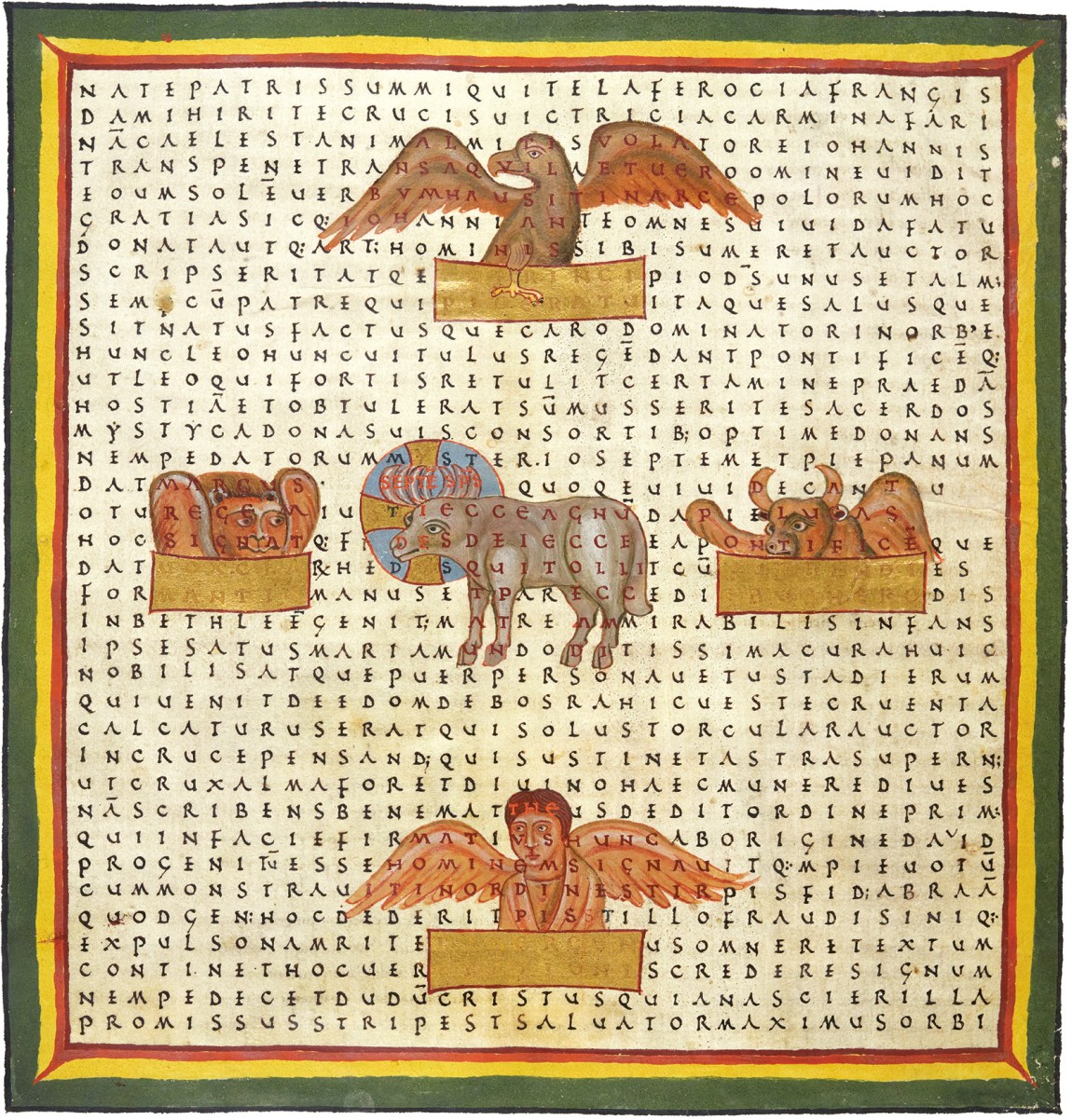

Angels and Saints is a deeply scholarly and playful work, in which the mind of an essayist meets the sensibility of a poet. It is as lovely an object as its subject might require, illustrated by the grid poems of Hrabanus Maurus (circa 780–856), with an additional note on their complexities by Mary Wellesley.

Weinberger moves from the ancient to the modern, from Pseudo-Dionysius to Rilke, in one simple step. (Angels can move anywhere, through all time, and be there all at once.) Pacing below the castle at Duino, near Trieste, the poet hears a voice from the raging storm and writes, “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic orders?” Weinberger supplies a list:

Nadiel,

the angel of migration;

Memuneh,

the dispenser of dreams;

Maktiel,

who rules over trees;…

Most of these ninety or so names can be found in Gustav Davidson’s A Dictionary of Angels (1967), which draws heavily on kabbalistic medieval manuscripts, as translated by scholars in the nineteenth century, as well as on Islamic sources. Weinberger has removed much of the detail accumulated by Davidson, leaving a single characteristic for each angel that feels either essential or arbitrary:

Hanum,

the angel of Monday;

Taliahad,

the angel of water;…

The result is a work of restoration and of new strangeness: it is a list that questions the way we make categories. The last angel here is Azrael, “who is forever writing in a huge book and forever erasing what he wrote: the names of the born and the names of the dead.”

Weinberger likes angels of books and pens and librarians. There are dictating angels and one who helps writers when they are disheartened. He tells of books that contain secret knowledge, many of them lost: Tertullian’s About Paradise, “which perhaps held some answers,” and the five thousand pages dictated by the angel Azariah to the paralyzed Maria Valtorta (Italy, 1897–1961), which are “unfortunately…on the Vatican list of forbidden books.” There is a sense that texts become less real or accurate as they move away from some mystically inspired original, now disappeared.

The second part of the volume is dedicated to brief lives of the saints in which Weinberger returns to early sources in order to refresh a sense of wonder, or of banality. He is now in Catholic territory. The staple of modern hagiography is The Lives of the Saints (1756–1759) by Alban Butler, various revised editions of which might still, just about, be found in Catholic libraries. These volumes work through the year, a saint for every day. Their flat narrative tone yields the occasional miracle, but there is a strange mixture of dullness and alarm, and an emphasis on virginity and gore. Many of the beatified were early Christian martyrs who were hard to kill, and the details of their deaths receive more space than the manner of their lives. (I will never find again those two Roman martyrs who died by being turned upside down while milk and mustard were put up their noses, nor check through the multiple volumes to see if I dreamed this, which surely I did not.)

Weinberger’s list sidesteps this interest in the (salable) body parts of the holy and incorrupt. He makes no mention of the various self-mutilating virgins who plucked out their eyes in response to the admiration of their suitors. More crucially, he resists a humanist biographical mode, returning instead to the folkloric accounts that medieval hagiographies were based on. These are texts in which the literal is not yet privileged over the wonderful, and the early entries in Weinberger’s lists of “Brief Lives” are cheerfully miraculous on a small scale:

Genesius of Arles

(France, d. 303 or 308)

A decapitated martyr, his body was buried in France but his head was transported “in the hands of angels” to Spain, where he is invoked as a protection against dandruff.

Weinberger provides no bibliography, but it is clear that the account of Saint Columba (521–597) is not drawn from Butler, or even from the writings of the Venerable Bede, but from Adomnán’s Vitae Columba (as translated by Richard Sharpe), which was written a generation before Bede. Some of Adomnán’s facts come from earlier texts again, including “Amrae Coluimb Chille,” which is commonly said to be the first known poem in the Irish language. This is a panegyric written on the occasion of Columba’s death by the blind poet and subsequent saint Dallán Forgaill. (It is said that his sight was regained in the writing of the poem.)

So it is quite astonishing to see Weinberger reproduce the cadences, exaggerations, and inversions of early bardic Gaelic poetry in his modern account of Columba: “He could see behind himself. He could proofread the copies of sacred books without looking at them. When he chanted, his voice sounded normal to those next to him, but could be heard a mile away.”

Weinberger captures the playfulness of the marginalia found in medieval manuscripts, and also the serendipitous sense that the fragments that survive for us have been arbitrarily preserved. Lives are listed chronologically, more or less. The early saints are magical, and work close to the animal world. In the sixth century the Irish Ailbe of Emly (died 528) “could turn a cloud into a hundred horses.” The French saint Vedast (died circa 540) “resurrected a goose.” As we move through time, they gain something by way of personality—John the Almsgiver (Cyprus, 552–620) “never spoke an idle word”—while their miracles become more particular and therefore odd: as a newborn, Nicholas Politi (Sicily, 1117–1167) “refused to nurse on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays.” There are also darker intimations of history (that other angel) up ahead, including Adolf of Osnabrück (Germany, 1185–1284): “A charitable bishop, Hitler was named after him.”

Wisdom collapses into banality in the proverbial sayings of John Climacus (Egypt, 579–649), which end with two koan-like but rather empty insights: “Waves never leave the sea” and “When we draw water from a well it can happen that we inadvertently bring up a frog.” Later saints have lives that are just a play on words: “A parish priest, he was killed by his nephew, a parish priest.” Some are fully contradictory or dreadful, like Mary-Margaret d’Youville (French Canada, 1701–1771), who built hospitals and orphanages using slave labor. This chapter ends with Francis Dachtera (Poland, 1910–1944): “A priest, he died from the medical experiments performed on him at Dachau.”

The last life in the book is Edvige Carboni (Italy, 1880–1952), a stigmatic, visionary, and currently in line for beatification. She had the gift of bilocation, her nightdress had burn marks on the inside, and she levitated while at prayer. The devil broke her plates, undid her knitting, and turned her money to ashes. Jesus made her laundry white. “While I was praying in front of the Crucifix,” she wrote in her diary, “a person appeared to me suddenly all in flames, and I heard a voice say: ‘I am Benito Mussolini.’”

Perhaps Weinberger does not provide a bibliography because it would be so many times thicker than the book itself. There is a lifetime’s scholarship here. Tracing the details brings you through the maze of medieval manuscripts and translated early sources available online, leading to many open tabs and disappearing footnotes, not unlike the missing volumes of Tertullian. Not unlike, indeed, what happens when you click around trying to chase the religious right through a contemporary folklore of marvels and frights, whose monstrous bestiary has its origins in third-century Christianity.

Try, if you are feeling hardy, the webpages of the masculinist Alt-Christian movement, with their Nazified graphics, talk of the devil, and many ads about cheating wives and erectile dysfunction. These men, like millions of modern Americans, rely on the Bible, an ancient and contradictory text that is endlessly open to interpretation, whether marvelous or banal. As Luhrmann notes of evangelical meetings:

Often, a member will describe how God confuses her in one way or another. Someone else will remind her how much God loves her, as if God couldn’t be disappointed in her—and then go on to puzzle her way through another passage in which Jesus does something odd.

This Issue

March 11, 2021

What Dignity Demands

The Truth About Museveni’s Crimes