It was about 7 PM on May 2, 1980, when Tayseer Abu Sneineh set out from a cave hideout on the outskirts of Hebron with three other Palestinian militants. Like his comrades, Abu Sneineh, a twenty-eight-year-old math teacher, was a member of Yasser Arafat’s Fatah group, the leading faction of the Palestine Liberation Organization. The PLO guerrillas received their instructions from Abu Jihad, one of Arafat’s top aides. They would carry out what was then the deadliest terrorist attack ever perpetrated in the West Bank, which had been occupied by Israel since the conclusion of the 1967 war.

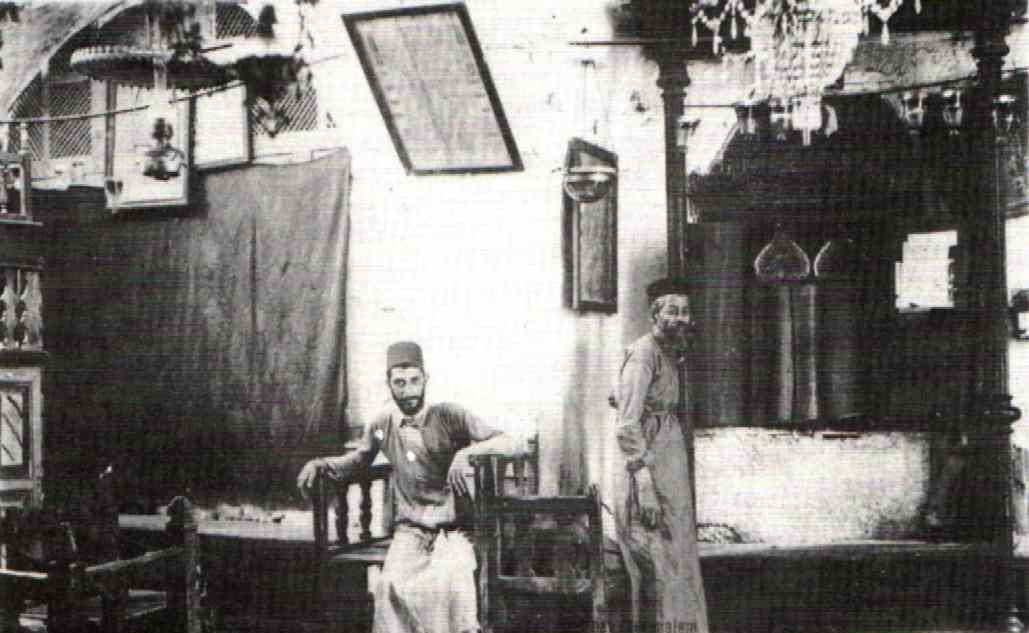

Armed with assault rifles, hand grenades, and improvised explosive devices, they took their positions at a building across from the historic Beit Hadassah complex. The building had housed a Jewish-run medical clinic that served the Arabs and Jews of Hebron until the massacre of 1929, when sixty-seven Jewish men, women, and children were murdered in a pogrom carried out by their Arab neighbors. On August 24, 1929, a mob armed with swords, clubs, and daggers went from house to house in Hebron, slaughtering, raping, hanging, and, in some cases, castrating and burning their Jewish victims alive. Those who survived were forced to leave the city, effectively exiling Hebron’s ancient Jewish community.

The massacre in Hebron was one of the worst pogroms ever perpetrated outside of Europe before the Holocaust, and it was instigated by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, who later allied himself and his people with Germany’s Nazi regime. The riots were driven by rumors that Jews were trying to take over the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Some fifteen miles to the north in Jerusalem, the mosque sits atop the ruins of ancient Jewish temples, a site known as the Temple Mount.

That Friday night in May of 1980, Abu Sneineh’s eyes were fixed on a group of some fifty religious Jews making their way toward Beit Hadassah to visit the women and children who had been squatting in the complex for a little over a year. The women had moved into the long since abandoned building in order to pressure the Israeli government to allow Jews to return to Hebron, where there had been a nearly four millennia-long history of Jewish presence, before their violent expulsion in 1929.

The Jewish connection to Hebron dates back to biblical times. By biblical account, Hebron was King David’s first capital, before Jerusalem. For centuries, Jews lived in the area surrounding the Tomb of the Patriarchs, the two-thousand-year-old burial plot that surrounds caves where Abraham, Sarah, and the other forefathers and foremothers of the Jewish people are believed to be buried. Built by Herod the Great, the Jewish King of Judea, in the first century BC, it is thought to be the oldest continuously used prayer structure on earth. Some six hundred and fifty years after its construction, it was turned into the Ibrahimi Mosque by Muslim conquerors of the area, named for the prophet Ibrahim, as Abraham is revered in Islam.

Today, it is both a synagogue and a mosque. According to both faiths, Abraham purchased the cave and the field surrounding it to bury his wife Sarah. Abraham is believed to be the father of both the Jewish and Islamic people, through his sons Isaac and Ishmael. The children of Abraham named the city that grew around the caves after him: Hebron’s name in both Hebrew (Hevron) and Arabic (Al-Khalil) means “friend,” as in friend of God.

After Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan in 1967, descendants of the Jews who had been killed in 1929 and the early settler leader Rabbi Moshe Levinger tried to revive Hebron’s ancient Jewish community. Their efforts were repeatedly blocked by the Israeli government, which was mindful that allowing a high-profile settlement in such a sensitive place could be a dangerous provocation of Arab countries, and that it would be regarded as illegal activity by the international community.

While Levinger and his religious Zionist followers managed to live briefly in a Hebron hotel in 1968, and then in the Israeli military headquarters overlooking Hebron for three years, the government refused to acquiesce to their campaign to rebuild the Jewish community in Hebron, the largest city in the West Bank. The takeover of the derelict Beit Hadassah building by women and children led by Levinger’s wife, Miriam, was their latest tactic. “Hebron will no longer be Judenrein,” vowed Miriam Levinger at the time, appropriating the Nazi term for an area cleansed of Jews.

*

Each Friday night, after praying at the Tomb of the Patriarchs, young Jewish men and women would visit the women and children in Beit Hadassah to recite the Kiddush blessing, sanctifying the Jewish Sabbath. The presence of this predictably large crowd was precisely why Abu Sneineh’s group had chosen this place and time for its attack. As the crowd approached, with Moshe Levinger leading the way, Abu Sneineh stood in a darkened doorway clutching a submachine gun. Other militants peered down from the roof above with hand grenades and Kalashnikovs. They waited for the whole group to arrive.

Advertisement

Seconds after Rabbi Levinger opened the gate to Beit Hadassah and said, “Shabbat Shalom,” the Palestinian attackers opened fire. After spraying the crowd with bullets, and hurling grenades and homemade bombs, the militants ran for cover in the nearby Muslim cemetery, and from there made their escape back to the cave. Six Jewish civilians died in the attack, and twenty were injured. Five of those killed were yeshiva students.

The consequences of the attack went far beyond the casualties of that night. Even as Levinger’s followers mourned their dead, the event proved a huge boon to the project they’d begun in Hebron. Under the auspices of the religious-nationalist organization Gush Emunim, which Levinger cofounded in 1974, this messianic movement spurred Israel’s official settlement enterprise.

The Israeli government, then led by Likud leader Menachem Begin, responded to the terrorist attack in Hebron by bowing to the religious Zionists’ demands. This was a defining moment for Rabbi Levinger, who finally got what he’d been fighting for since 1968: official backing to rebuild Hebron’s Jewish community.

It started small, with a few families moving into a handful of buildings that had been owned by Jews before the massacre of 1929 forced their abandonment. Beit Hadassah, where one of the most horrific attacks of 1929 took place, was one of them. The community that was rekindled that night swiftly became the vanguard of the settlement movement.

Now, forty years after the Beit Hadassah attack, Hebron is home to some eight hundred Jews, living among more than 250,000 Palestinians. Because of the religious history and symbolism the city holds, Hebron continues to attract the most ardent members of the settler movement. The Jews of Hebron today see themselves as spiritual heirs to the community that was extinguished in 1929.

In September 1980, Israel arrested Abu Sneineh and the other men who had carried out the attack. Sentenced to life in prison, they were all, in fact, released shortly after in prisoner exchanges between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. Abu Sneineh was one of nearly five thousand Palestinian prisoners freed in 1983 in exchange for six Israeli soldiers who had been held hostage after they were captured by Fatah fighters at an Israel Defense Forces outpost in central Lebanon in 1982. After his initial deportation to Algeria, Abu Sneineh was able to return to the West Bank via Jordan, along with other exiled PLO members, after the signing of the first Oslo Accord, in 1993. Welcomed back as a resistance warrior, he quickly became head of the Hebron Waqf, the Muslim authority that oversees the city’s mosques, including the Ibrahimi Mosque.

*

Twenty years later, Abu Sneineh’s prestige in Hebron had not faded. In 2016, Fatah—then led by Arafat’s successor, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas—chose Abu Sneineh as the party’s candidate in the following year’s election for mayor of Hebron. In announcing his candidacy, Fatah called Abu Sneineh a hero and his attack “one of the most important battles and acts of bravery of the Fatah Movement.” On May 14, 2017, following a campaign in which he, too, embraced his part in the Beit Hadassah terrorist attack, Abu Sneineh was duly elected. No election has been held since, and none are on the horizon. There are no official term limits, and the Palestinian Authority tends to hold elections only when politically convenient.

Mayor Abu Sneineh is not the only terrorist to be revered in Hebron. In February 1994, an American Jew originally from Brooklyn perpetrated a deadly atrocity in the city. Baruch Goldstein, a doctor then living in the nearby settlement of Kiryat Arba, gunned down dozens of Muslim men and boys praying at Ibrahimi Mosque during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. Goldstein, a follower of the extreme religious-nationalist Rabbi Meir Kahane, killed twenty-nine worshippers and wounded more than a hundred others before being overpowered and beaten to death by survivors of his attack.

In the immediate aftermath, the Israeli government clamped down on Jewish extremists and criminalized the Kahanist Kach Movement. But if you ask almost any Jewish settler living in Hebron today what they think of Goldstein, they describe him as heroic. His gravesite in Kiryat Arba—bearing the inscription “To the holy Baruch Goldstein, who gave his life for the Jewish people, the Torah, and the Land of Israel”—became a shrine for the hardcore settler movement. Militants from the Islamist group Hamas, settlers claim, were planning a major attack against the Jews of Hebron, and so, in their telling, Goldstein prevented a massacre.

Advertisement

There is thus a certain symmetry in the veneration of terrorists as popular heroes in Hebron, one that reflects the city’s bitter status as a frontline of the occupation. The rise of Mayor Abu Sneineh, who shows no more remorse for the attack he carried out than Goldstein’s admirers do for his, illuminates the way Hebron has become the bleeding heart of this conflict.

*

Symptomatic of Hebron’s seemingly irreconcilable divisions is its officially codified geography. The side that is controlled by the Palestinian Authority, which makes up 80 percent of the city’s territory and is where the vast majority of its residents live, is known as H1. H2, the remaining fifth of Hebron that is controlled by Israel, is a depressing zone of ancient stone buildings and narrow streets filled with armed soldiers, checkpoints, and barbed wire. It is otherwise largely devoid of the usual signs of urban life, whereas H1 is a bustling Arab city that reflects its status as the economic hub of Palestinian life in the West Bank. Israeli citizens are forbidden from entering H1, and the movement of Palestinians within H2 is heavily restricted by soldiers and checkpoints.

Just before Covid-19 hit Israel and the Palestinian Territories, I spent several months doing research and reporting in Hebron. Until then, I had been to Hebron only once, and that brief visit, in 2011, was so upsetting that I never returned. I was a student at Columbia Journalism School on a one-day tour with Breaking the Silence, an organization established by Israeli military veterans who had served in the Occupied Territories (including in Hebron) and strongly objected to the injustices they were forced to carry out, such as nightly raids into Palestinian homes and beatings of those who resisted. Seeing how little freedom the Palestinians living under Israeli control in H2 have, I arrived at the same conclusion that many other young, progressive American Jews had: that in its quest for security, Israel was forsaking Jewish values and oppressing Palestinians in unacceptable ways. That day, a city that I had regarded as a monument to Judaism’s ancient past became for me a place that symbolized Israel’s moral unraveling.

Marco Longari/AFP via Getty Images

Palestinian protesters throwing stones at Israeli troops during clashes following a protest to demand the reopening of Shuhada Street, a part of the old city flanked by Jewish settlement enclaves and closed since the Goldstein massacre, Hebron, West Bank, March 1, 2013

Somehow, though, the need to better comprehend how the city of Abraham’s children had come to define the enmity between Israelis and Palestinians grew with time, and in late 2019, I returned to Hebron. I set out to speak with many Palestinians in Hebron, as well as the city’s Jewish settlers, but because of all that Mayor Abu Sneineh represented, it was clear to me that he would be an essential interlocutor. Across several interviews, he refuted any Jewish right of presence in the city. “This claim that the Jewish religion springs from here and it comes from Palestine, I will tell you this is absolutely not true,” the mayor insisted. “There is no holy place in Palestine which is linked with the Jewish religion through history,” he told me.

“What about the Tomb of the Patriarchs?” I asked. “The Ibrahimi Mosque is a Muslim holy site,” the mayor responded, holding up as proof a 2017 UNESCO declaration of the shrine as a Palestinian World Heritage Site under threat, as though that fact negated its ancient Jewish history. “This occupation, Israel, has been built on a false narrative,” he went on. “The world is now waking up to the Palestinian narrative.”

In a meeting with a group of foreign journalists in December 2019, days after Israel’s then defense minister Naftali Bennett approved a new Jewish neighborhood in Hebron, the mayor described the announcement as “a terrorist act against the Palestinian people.” When I later asked Abu Sneineh about his own terrorist attack, he argued that it was carried out not on a crowd of Jewish civilians returning from prayer at the Tomb of the Patriarchs but against a group of armed extremists and soldiers. This claim is contradicted by contemporary news reporting: a few of the settlers were armed, but most of the group were not, and all of the victims were civilians. “It is well known that the Jewish community is raised on extremism in this area,” he said. “We are against violence. We want to live in peace.”

Like nearly every inch of Hebron, the land upon which the new Jewish neighborhood will be built has a tangled history—though it all comes back to 1929. Until 1994, it was a bustling Arab market. Situated on once-busy Shuhada Street, the market was closed by the Israeli military in the aftermath of Baruch Goldstein’s rampage at the Ibrahimi Mosque, which was followed by Palestinian riots. Shuhada Street, still guarded by Israeli soldiers, is now mostly deserted, with Palestinian access restricted. Before the area became an Arab market, however, it had been Jewish property. Purchased in 1807 by Rabbi Haim Bajayo, a leader of Hebron’s Sephardic community, the neighborhood was a center of Jewish life—until the 1929 pogrom, when Arab residents took over those Jewish homes. It was during Jordanian rule, which lasted from 1948 to 1967, that the area was taken under state custodianship and turned into a market.

“The establishment of the Jewish quarter will lead to…the Judaization of the entire area,” the mayor told the journalists gathered in his office. There had already been a forced expulsion of Palestinians from H2, the side of Hebron controlled by Israel, Abu Sneineh continued. When, in 1997, during the period that followed the Oslo Accords, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the late Yasser Arafat signed the Hebron Protocol dividing the city into H1 and H2, there were 35,000 Palestinians living in H2. Today, although the Palestinian population generally has grown, that number had fallen to 34,000 in 2017. The size of the Jewish population of Hebron has stayed steady for more than a decade, at around eight hundred, the same as it was in 1929.

I asked Abu Sneineh if he opposes Jews living in Hebron. “We are not against Jewish existence as Palestinians [my emphasis], who lived in Hebron before, as Palestinians,” he responded. (In other words, he would countenance a return to the situation that pertained prior to Israel’s establishment in 1948, when Jews and Arabs living under British and Ottoman rule were all considered Palestinian.) When I questioned him specifically about the massacre of 1929, he told me that the atrocity was perpetrated by the British authorities, not by the Arabs of Hebron. There is no evidence to support this claim.

Although the mayor’s revisionist history stunned me at the time, I came to understand that such views are mainstream in Palestinian Hebron. In a separate conversation with Abu Sneineh’s spokesman, he repeated the same canards about the British carrying out the 1929 massacre and about the Jewish people having no history in “Israel” (his air quotes). I heard the same alternative facts from religious officials at the Ibrahimi Mosque. “The Jews have no right to be here,” said Sheikh Hefzi Yassin Abu Sneineh, an imam and manager of the mosque. (He and the mayor are distant relatives, but since theirs is one of the largest clans in Hebron, it is a very common name.)

When I expressed shock at the fact that so many Palestinians could believe that Jewish people have no roots there, my Arabic translator, a young woman from Ramallah, confirmed that most Palestinians share this view. I decided to test this theory on two young men sitting on a bench outside the Hebron municipality, drinking coffee. Ahmad Muhtaseb and Bara’a Bilhem, both accounting students at Hebron University, told me they’d never heard of the 1929 Hebron massacre. “The Jews have no connection here,” said Muhtaseb. Bilhem agreed: “Jews have no roots here.”

*

Such denialism—about the reality of millennia-long Jewish presence in the land, let alone about the established facts of the 1929 pogrom—was difficult to hear. Yet, in my years of reporting from Israel, I have also heard right-wing Israelis insist there was no historical precedent or rationale for a state of Palestine, a claim they would justify by saying that Palestine was never self-governing but always ruled by outside forces, be they Roman, Ottoman, or British. Since the idea of annexation of the West Bank, floated last year by Prime Minister Netanyahu, has entered mainstream Israeli discourse, there is no shortage of advocates among the political heirs of Rabbi Levinger for wholesale “population transfers”—in other words, mass deportations—of Palestinians.

Hebron epitomizes the clash of competing, exclusive claims that defines this conflict. While the massacre of 1929 haunts every corner of the old city for the Jews of Hebron, the Palestinians of Hebron hold up Baruch Goldstein’s mass killing as proof of the settlers’ true intent. Both sides have their narratives that the other is bent on ethnic cleansing.

“We wouldn’t need the checkpoints or the soldiers guarding us if they weren’t constantly trying to kill us,” Tzipi Schlissel, a Hebron settler, told me last year. Schlissel, a fifty-five-year-old mother of eleven, had been the victim of an attempted attack on a street near her home by a Palestinian during the so-called “Knife Intifada” of 2015–2016. An armed settler shot and killed her would-be assailant as he was about to stab her.

Like the massacre of 1929, that 2015–2016 uprising was also fueled by false rumors that Jews were trying to take over Al-Aqsa. The forces of history that have animated a hundred years and more of conflict in Palestine are far larger than Hebron alone, but the city has become ground zero of that conflict today, not in spite of its sacred history but because of it. It is precisely the holiness of this place to both Jews and Muslims that attracts extremists on both sides. Rather than serving as a focal point for the shared history of Islam and Judaism, Abraham’s burial place has instead become a focal point of what is, in its essence, a holy war between two people with a common spiritual forefather.

Schlissel’s close call with deadly violence was, sadly, no anomaly. Her own father was murdered in his Hebron home by a local Palestinian in 1998. In this intimate, century-long history of bloodshed, you have to go back to the beginning to find a story with a different outcome. In 1929, it was an Arab man who hid Schlissel’s grandmother inside his home and saved her from the mob.