In the summer of 1932 Eric Williams arrived in England from the British colony of Trinidad. Like most of the island’s population, his family was so poor that he and his eleven siblings had rarely tasted milk. But from his earliest youth his father, a disillusioned postal clerk, obsessively pressured him to achieve academic success. There were no universities in the West Indies; few Trinidadians progressed beyond primary school, and almost all professions were reserved for whites. Yet Williams won a coveted government scholarship that enabled him to continue studying beyond the age of eleven, then an even rarer bursary to complete his secondary schooling, and finally, after three years of trying, one of the island’s two annual scholarships to a British university. He sailed for Oxford to take an undergraduate degree in history.

The white Englishman in charge of Trinidad’s Board of Education recommended him to one of the university’s colleges, the rich, ancient centers of its intellectual and social life. “Mr Williams,” he wrote, “is not of European descent, but is a coloured boy, though not black.” This did not help. He entered Oxford as a member of St. Catherine’s Society, the decidedly déclassé association for students who could not afford the high costs of a college. From then on, Williams flourished. He read insatiably, graduated at the top of his class, and entered the competition for a fellowship of All Souls College, Oxford’s greatest prize. He also embarked on research for a doctoral thesis about the ending of British slavery in the West Indies. This was a deeply unfashionable subject. Even in Trinidad, Williams had only ever been taught about the European past. A handful of Oxford’s faculty studied colonial history; the rest regarded it, he observed, with “general contempt.”

Yet in every other respect the university was not just proud of the empire but instrumental in sustaining it. Its lecturers taught of the “unseen superintending Providence controlling the development of the Anglo-Saxon race,” exhorted “reverence before the majestic fabric of British [imperial] development,” and, above all, inculcated the uplifting message that, whatever its past or present shortcomings, the British Empire was a profoundly moral undertaking whose spread benefited its countless subject peoples. Across the globe, Oxford’s graduates filled the upper ranks of colonial administrations. Its professors often had backgrounds in overseas service and were influential in policymaking. More than any other university, it actively promoted imperialism, from the corridors of government down to the indoctrination of schoolchildren. Between 1911 and 1954, Oxford University Press’s best-selling History of England, by Rudyard Kipling and C.R.L. Fletcher, a fellow of All Souls and Magdalen, explained to girls and boys that the settlement of Australia had been easy because it contained “nothing but a few miserable blacks, who could hardly use even bows and arrows,” that in Africa “the natives everywhere welcome the mercy and justice of our rule,” and that West Indians were

lazy, vicious and incapable of any serious improvement, or of work except under compulsion. In such a climate a few bananas will sustain the life of a negro quite sufficiently; why should he work to get more than this? He is quite happy and quite useless.

No corner of Oxford was more devoted to the imperial mission than All Souls. Its grand eighteenth-century buildings were dominated by the huge Codrington Library, named after the West Indian slave owner whose benefaction enriched his old college. Its recent and current fellows included cabinet ministers, senior imperial administrators (including three viceroys of India), and the longtime editor of The Times, an immensely influential and energetic agent and proponent of colonialism.

It was also the home of Oxford’s professor of colonial history, Reginald Coupland, whose acclaimed writings perpetuated the dominant view of the British Empire as a great civilizing enterprise. Through its benign, nurturing “trusteeship” of less developed peoples, Coupland explained, the empire would in due course evolve into a “Commonwealth” of mature, self-governing nations—headed, naturally, by the British. In 1931, when Gandhi visited Oxford after inspiring a mass campaign of civil disobedience across the Indian subcontinent, Coupland duly reminded him of the historical logic of imperial destiny, which decreed that only cooperation and patience, not defiance, could lead to eventual self-rule. (While he was only a peasant, not a professor of history, the Mahatma responded coolly, that was not his understanding of how either the Americans or the Irish had, in fact, obtained their independence.)

Like other colonial historians, Coupland also helped shape British imperial policy. In 1937 his report for the Royal Commission on Palestine concluded that Arab–Jewish conflict was “irrepressible” because the two “races” were intrinsically antagonistic; it recommended territorial partition as the only solution. In the early 1940s he participated in failed government efforts to persuade Indian nationalists to support the British war effort and suspend their calls for independence. Analyzing “the Indian Problem” in depth for his All Souls colleague Leo Amery, the secretary of state for India, he was one of the first to raise the notion of partition; when this idea was hurriedly implemented in 1947, it was another fellow of All Souls—a barrister who’d previously never traveled east of Paris—who was put in charge of hastily drawing the fateful lines that separated Pakistan from India, resulting in 10 to 20 million refugees and mass carnage.

Advertisement

In 1935 the fellows of All Souls interviewed Eric Williams. More than thirty years later, he still smarted at the memory—not of losing out to better candidates but of being treated as a racial inferior. What was his opinion, he was asked, on “whether advanced peoples have any right to assume tutelage over backward peoples?” One fellow defended the recent Italian occupation of Ethiopia, the only free black African nation besides Liberia; another openly stared at Williams in the street because of the color of his skin. It was clear that “natives” didn’t belong there. The warden of All Souls advised him to serve his own people by returning to Trinidad. So did the dean of St. Catherine’s: “You West Indians are too keen on trying to get posts here which take jobs away from Englishmen.” For the English to transplant themselves around the world and rule over others was a natural right, but for a darker-skinned colonial to presume to do the reverse was insupportable.

He did eventually return home, convinced that a people’s grasp of their own history was the key to their sense of identity. Before long his educational mission of addressing open-air crowds on the history of slavery and the Caribbean morphed into a political campaign for freedom from British rule. But he never lost sight of the link between contemporary politics and understandings of the past. Soon after leading the new nation of Trinidad and Tobago to independence in 1962, he noted that Britain’s condescending modern treatment of its former West Indian colonies derived principally from “the fact that for so many centuries they have been regarded as satellites and subjected to the most humiliating propaganda”—the most pernicious of which were “the shams, the inconsistencies, the prejudices of metropolitan [i.e., British] historians.” Independence should mark a fresh beginning, a reimagining of national identity. It was not, as the British liked to pretend, a consummation of the imperial project, a vindication of their benevolent tutelage of “subject races.” That theory of history “sought only to justify the indefensible and to seek support for preconceived and outmoded prejudices.” Singling out Coupland, he savaged the idea of the empire’s moral justification: “British historians wrote almost as if Britain had introduced Negro slavery solely for the satisfaction of abolishing it.”

But old mental habits die hard. “I was…all in favour of the British Empire,” reminisced another All Souls historian, sixty years after he’d interviewed Williams for the fellowship—after all, “weren’t Africans and Indians happier, prevented from massacring each other, in those better days?” That is still a mainstream view. In 2016, when African and other antiracist student activists at Oxford began a (still unrealized) campaign to remove a statue of its great imperialist benefactor Cecil Rhodes, the university’s leadership responded belligerently. Its chancellor, Chris Patten, who’d studied history at Oxford in the 1960s and served as Britain’s last colonial governor of Hong Kong, told the BBC that if people weren’t prepared to show “generosity of spirit…towards Rhodes and towards history,” they didn’t belong at Oxford: “Maybe they should think about being educated elsewhere.” In other words: If you don’t like it here, why don’t you go back to where you came from?

As someone else once said, if studying history mainly makes you feel happy and proud, you probably aren’t really studying history. Over the past year, amid a new wave of critical scholarship, Britain’s imperial legacy has become one of the most fiercely contested battlegrounds of its culture wars. In September, when the National Trust, the charity that owns hundreds of the United Kingdom’s best-loved historic buildings, released a report detailing some of their connections to colonialism, it was greeted with outrage by Britain’s right-wing press and Conservative government. In the tabloid Mail on Sunday, Baroness Stowell, the Conservative chair of the Charity Commission, the official regulator of philanthropies, warned them not to “stray into party politics” or be “drawn into the culture wars.” Soon afterward, the commission opened an inquiry into whether the Trust’s research had constituted an illegal misuse of charitable funds. Meanwhile, Oliver Dowden, the secretary of state for culture, publicly instructed all UK museums that they must “defend our culture and history from the noisy minority of activists constantly trying to do Britain down.”

Advertisement

Most recently, in an attempt to push back against the wave of anger and activism that has been building since last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests, the prime minister’s office rushed out a shoddy, historically illiterate report on racial disparities in modern Britain that sought to downplay their deeply rooted, systemic character. It chided nonwhite Britons to acknowledge that “the UK had become open and fairer,” scolded them to “help themselves through their own agency, rather than wait for invisible external forces,” and lauded the UK as “a model for other White-majority countries.” Dismissing “negative calls” to decolonize the nation’s teaching of history, and the misguided motives of “people in the progressive and anti-racism movements,” it clumsily proposed instead

a new story about the Caribbean experience which speaks to the slave period not only being about profit and suffering but how culturally African people transformed themselves into a re-modelled African/Britain.

Modern British attempts to defend the empire and its legacies invariably take a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, there’s a disingenuous ethical claim: no one in the past realized that what they were doing was contentious, so we cannot criticize them. (Even leaving aside questions of retrospective judgment, men like Rhodes turned to educational philanthropy precisely to launder their dubious reputations—imperialism was never uncontroversial, even at its height.) On the other hand, there’s the fiction of “balance”: imperial unease is minimized by reducing public debate to the inane question of whether, all things considered, the empire was “good” or “bad.” Did Britain’s abolition of slavery not cancel out the sin of its previous participation in the slave trade? Shouldn’t the introduction of railways to India count against the horrendous death toll of the many famines aggravated by British economic policies? Surely imperial rule prevented indigenous conflict and helped lesser nations “develop”? Lumping together all ethical, economic, political, and other considerations, and squinting hard to avoid questions of responsibility and viewpoint, was the empire not beneficial on the whole?

None of this is new: such balance-sheet historical apologetics have always been central to imperialism. In Time’s Monster, her impassioned, searching new book, Priya Satia explores how they were used to justify the unmistakable violence of Britain’s long rule over India, the crown jewel of its later empire. From the late eighteenth century onward, supporters of imperialism vindicated colonial actions by reference to a continually updated ideology of historical necessity. It had several components—the old Protestant idea of God’s providential guidance of the British nation; the more recent valorization of personal conscience, which made intent (rather than outcome) the ultimate ethical standard; and a new Enlightenment faith that all human societies passed through stages of development, from the “primitive” to the “civilized,” measurable by such criteria as their systems of agriculture, forms of government, and treatment of women. History was determined by providence, destiny, and natural laws of social development. Compared to these large, inexorable forces, human agents, especially if they were well-intentioned, could hardly bear much culpability for misfortune. What’s more, because the arc of history was supposed always to bend toward progress, even apparently destructive or immoral actions could be exculpated as likely to be “vindicated by history.” In the ethics of imperialism, final judgment is always deferred to the future.

Synthesizing an abundance of more specialized work by others and revisiting the subjects of her two previous books—on the eighteenth-century English origins of the global arms trade and on British spying in the interwar Middle East—Satia examines where these ideas came from and how pervasive they were. Even some of the severest nineteenth- and twentieth-century critics of colonialism shared the presumption that human history moved unstoppably forward along a single path, and that mere individuals could only enact what was predetermined. The effects of English rule in India were “devastating,” Karl Marx observed in 1853, yet this “dragging [of] individuals and people through blood and dirt, through misery and degradation” was also a historical necessity, for “England has to fulfill a double mission in India: one destructive, the other regenerating—the annihilation of old Asiatic society, and the laying the material foundations of Western society in Asia.” To Occidental eyes, Satia wryly observes, the suffering of subjugated peoples was invariably good for them: “merely birthing pain in the cause of some greater epochal labor.”

Yet as Time’s Monster shows, the idea of historical vindication originated in a deep sense of British guilt. In the late eighteenth century, faced with mounting evidence of imperial corruption, bloodshed, and misrule, Britons faced a crisis of conscience about the effects of their overseas endeavors. The origins of European empires were shameful, Adam Smith observed in 1776: mere “folly and injustice” toward “harmless natives” who had been brutally exploited, massacred, and enslaved. It was to redeem such sins, and the embarrassing loss of their American colonies, that the British after 1800 developed the idea that their global imperial mission was driven by a moral purpose. By eradicating slavery, freeing peoples from mental and physical bondage, spreading liberty, Christianity, and free trade, and replacing corrupt local manners and culture with their Western equivalents, they would extend civilization across the world.

In his huge, best-selling History of British India (1817), the tireless utilitarian reformer James Mill pronounced—without ever having set foot there or learned any of its languages—that the subcontinent was plainly a stagnant, ignorant, “barbarous” place, where time had stood still for centuries. True, its past colonial government by the East India Company had been a tragedy of stupidity and greed—but now, at last, going forward, the British had a great opportunity to replace India’s degenerate culture with modern norms and laws that would allow Indians to progress. Mill’s text became the leading handbook for British imperial officials in India as they set about that task; he himself, as well as three of his sons (including the eldest, the philosopher John Stuart Mill), entered colonial service.

The great Indian uprising against British rule in 1857, together with other mid-nineteenth-century indigenous rebellions across the empire, forced a rethinking of this optimistic historical script. What had caused such horrendous violence? Was it evidence of yet more imperial misrule? If not, why had the locals so willfully rejected British benevolence? In the late nineteenth century, most Britons settled on what seemed to them the most obvious answer: history, it appeared, proved not just that certain societies were superior to others, but also that “native” cultures were inherently primitive, violent, and resistant to progress. That not only justified their subordination but made it historically inevitable.

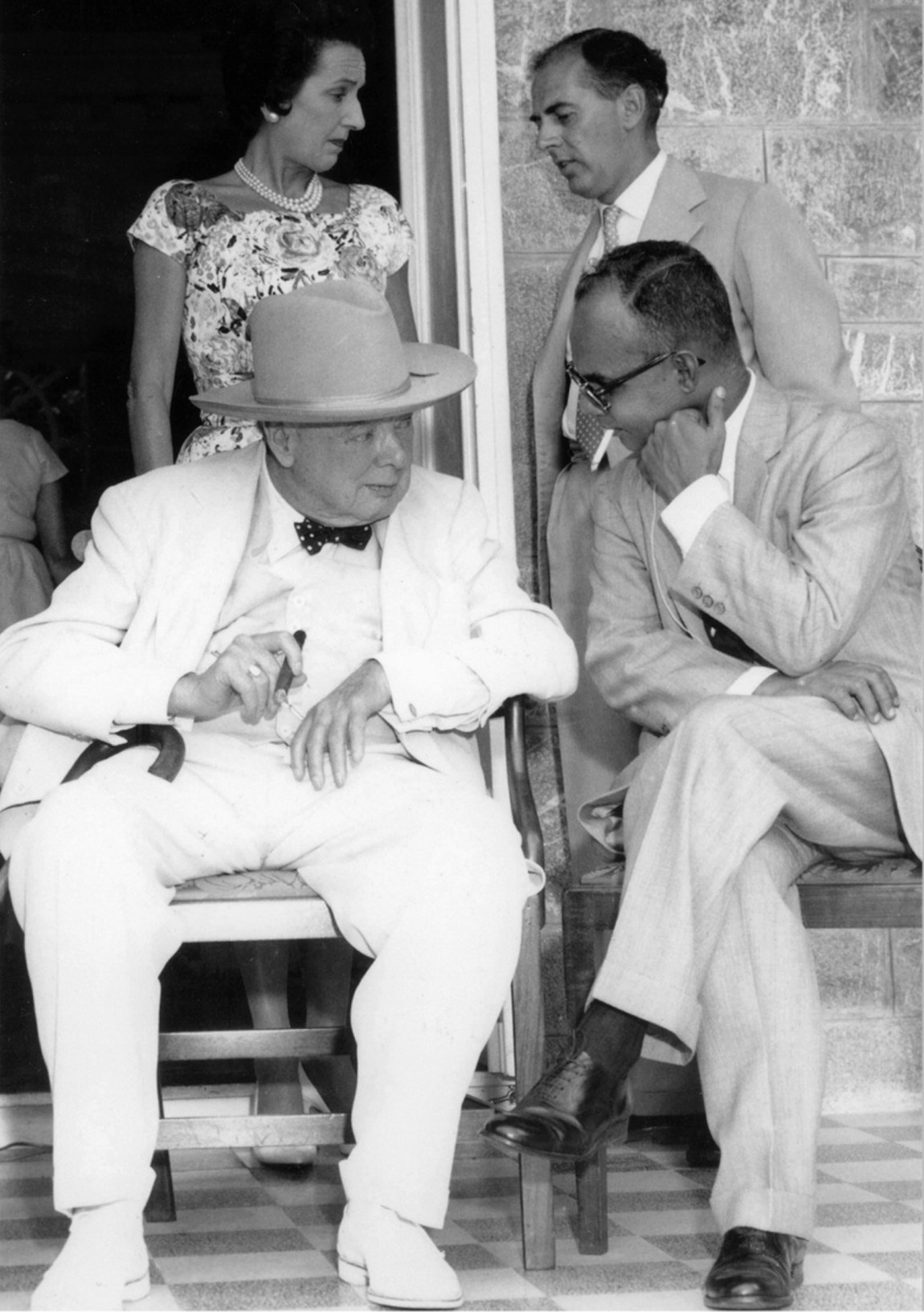

This outlook was buttressed by the rise of Social Darwinist and racist theories of societal development. Winston Churchill, for one, had long believed that “the Aryan stock is bound to triumph.” As home secretary in 1910, he proposed the mass sterilization and incarceration of “degenerate” Britons in order to strengthen their “race.” In a similar vein, he told Coupland’s Royal Commission on Palestine in 1937:

I do not admit…that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly-wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place. I do not admit it.

As prime minister in 1943, while millions of Bengalis were dying in a famine caused by British grain policies, he explained his refusal to send aid by invoking the vision of “Indians breeding like rabbits.”

The presumption that indigenous societies were intrinsically bloodthirsty, static, and backward gave imperialism a different but deeper ethical justification. The moral basis for colonial rule now became that it was the best way of preventing carnage and anarchy. Imperialism was, in Kipling’s phrase, “the White Man’s burden,” a noble duty to protect and tutor lesser peoples. Rather than trying to civilize them against their nature, the British after 1857 switched from “direct” to “indirect” forms of governance, preserving rather than replacing the seemingly atavistic religions, customs, and enmities of their colonial subjects. In addition to subordinating them as a whole, imperial rulers also increasingly subdivided indigenous populations into different castes, tribes, religions, and races. Each of these groups’ supposedly unchanging “native” traditions was now codified into a separate system of customary law and authority, through which it was to be governed.

The belief that non-European cultures were fixed in an alien, changeless moral universe also licensed further violence toward them. Orientals had different standards of ethics, a senior military officer assured Parliament in 1930: “The natives of a lot of these tribes love fighting for fighting’s sake…. They have no objection to being killed.” The aerial bombardment of Iraq was an entirely moral action, his colleagues concurred, for “life in the desert is a continuous guerilla warfare”: the martial Bedouin “do not seem to resent…that women and children are accidentally killed by bombs.” Their sensibilities, mused T.E. Lawrence (another interwar fellow of All Souls), were simply “too oriental…for us to feel very clearly.”

Meanwhile, because the British both benefited from indigenous disunity and presumed its timeless character, their imperial policies often exacerbated social conflict. By ordering fluid communal relations into fixed caste, tribal, and religious identities, and giving such sectarian labels greater legal and territorial significance, they politicized them in disastrous new ways—for example, by writing caste into Indian censuses and inserting rigid identity categories into law. One great champion of such efforts was the colonial administrator and anthropologist Herbert Risley, whose influential definitions of caste portrayed it as a racial category, corresponding to particular nose and head sizes. In 1905 he also masterminded the division of Bengal into two separate provinces, in order to weaken the nationalist movement. “One of our main objects,” he advised the viceroy, “is to split up and thereby weaken a solid body of opponents to our rule.”

Whenever colonial violence subsequently erupted, it was blamed on ancient hatreds, rather than the insidious effects of such imperial interventions. And as ethnic and cultural homogeneity became central to European notions of nationhood, it further justified the designation and displacement of “minority” populations in the colonies, and the wholesale division of their territories: hence the similar partitions, for example, of Ireland and India. Once again, the moral responsibility for any resulting bloodshed lay not with the dispassionate, benevolent colonial custodians but with the hot-headed, irrepressibly antagonistic “natives.”

Satia regards these changing imperial ideologies primarily as ways in which the British “suppressed” their “bad conscience about empire,” rather than as the untroubled rationalizations of people operating according to moral codes different from our own. One of the unresolved tensions running through Time’s Monster is how far it’s possible or helpful to conceive of conscience, and the ethical problems raised by imperialism, as timeless and essentially ahistorical. The book also grapples with the legacy of Anglophone history as an imperialist discipline. How should postcolonial historians approach their task? Perhaps, Satia suggests, it’s time to jettison our modern presumptions about the flow of time and the centrality of human endeavor altogether and “reconsider history as cyclical, if not aimless.” Not all these meditations are entirely convincing, but they usefully highlight what is at stake, even today, in writing about the empires of the past.

As a political scientist rather than a historian, Mahmood Mamdani is chiefly interested in how imperial legacies continue to shape our present world. Much of his previous work has analyzed the effects of nineteenth- and twentieth-century colonialism on modern African politics. His provocative, elegantly written new book, Neither Settler nor Native, restates and extends those arguments across a wider timespan and geography, with the aim of understanding the sources of the extreme violence that has plagued so many postcolonial societies. Mamdani traces its roots to the Western invention of the nation-state itself—a polity of a majority-ethnic or religious “nation” in which alien minorities are merely tolerated. In much the same way, he contends, colonial power invariably distinguishes the superior nation of settlers from the backward “natives” around them. As he notes, the first overseas population the English attempted to “civilize” were the Irish, and large-scale ethnic cleansing of indigenous peoples, expropriation of their land, and the establishment of settler plantations took place across the British Isles and the Americas as well as in Asia and Africa. The pathologies of postcolonial civil wars and genocide are directly connected to the history of what “civilized” nations have long done at home.

To make this case, Mamdani begins in the West. As he points out, the US was not founded as a nation of immigrants but of colonial settlers, who willfully exterminated the territory’s indigenous peoples, stole their land, defined them in ethnic terms, subjected them to inferior legal status, and confined them to arbitrarily assigned “tribal” territories, justifying all this in exactly the same ways as European powers did in their colonies. Even today, American Indians and their reservations are, both ideologically and practically, perpetually trapped in the same subordinate status that was imposed on “native” peoples under British imperial rule. (Mamdani eschews the term “Native American” for falsifying their true relationship to the settler nation—casting them as the original inhabitants of a political community that in fact has never treated them as equal members.)

In Europe, he maintains, the aftermath of World War II created a pernicious template for how to deal with state-based extreme violence. Instead of acknowledging that the Nazi genocide was a deeply political project, the Nuremberg tribunal, dispensing hypocritical victor’s justice, merely treated it as an accumulation of war crimes by individuals. Meanwhile, the Allies continued their own efforts at European and colonial ethnic division and expulsion, in order to create homogeneous nation-states out of territories with multiethnic and multinational populations. In the late 1940s they systematically expelled tens of millions of Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, and embraced the foundation of Israel on similar ethno-nationalist grounds. The “disentanglement of populations” in Europe would be a huge task, Churchill told the House of Commons in 1944, but a necessary one: henceforth, “there will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble…. A clean sweep will be made.” Cleansing and purifying have always been the preferred euphemisms for ethnic and religious dispossession and bloodshed.

These days, the standard response to extreme violence, whether in Yugoslavia, Rwanda, or Sudan, is to focus on restoring the rule of law and pursuing individuals for crimes against human rights. That Nuremberg-inspired model, widely criticized in its own time but resurrected after the end of the cold war, not only perpetuates the poisonous politicization of racial, ethnic, and religious identities, as Mamdani points out, but is also futile in situations of civil war. Its ahistorical approach only reinscribes identity-based divisions while ignoring their political causes—not least the national character of the state that is supposed to guarantee justice. To illustrate the limitations of the crime-focused approach to postcolonial conflict, Neither Settler nor Native explores the histories of Sudan and of Israel/Palestine. In the former, ethnic identities that were politicized, territorialized, and internalized through colonial rule continue to dominate violent postcolonial struggles for power. In the latter, the persistence of essentially colonial laws and attitudes toward nationhood has entrenched the legal, territorial, and political subordination of non-Jewish citizens and inhabitants.

In contrast, the book holds up the inspiring trajectory of South Africa from racist heartland to truly postcolonial state. That transformation came about not through its Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which Mamdani dismisses for its “perverse” Nuremberg-like focus on individual culpability, but because the ending of apartheid was achieved through a process in which colonial ethnic identities were, for once, not sharpened but gradually depoliticized. By at least partly dismantling the many legal and political distinctions between settlers and “natives,” and reforming their constitution and laws accordingly, South Africans have been able to begin reimagining their shared community not as one of victims, perpetrators, bystanders, or separate nations, but as a collective of survivors. That, Mamdani suggests, offers a hopeful model for how to overcome the legacies of colonialism. (Though it goes unmentioned, the Northern Irish peace process presumably would also fit his model of political decolonization.)

One limitation of Neither Settler nor Native’s penchant for bold but selective abstractions is that its argument implies that postcolonial politics have always been dominated by the colonial ideologies of race, tribe, and nation-state. Yet this approach itself reinforces a particular nationalist teleology. Internationalist ideologies hardly feature in the book, even though they have been central to the postwar European endeavor to prevent resurgences of ethno-nationalist violence—and were equally important to the leaders of many newly independent postcolonial territories. Instead of the tired national structures of the past, Eric Williams in 1959 urged the soon-to-be independent peoples of the Caribbean, they should seek above all to forge regional and global associations, “in these days of Bandung, Pan Africa, Arab League, British Commonwealth, Pan America, United Nations, European Common Market.” His inspirations were not colonial but cosmopolitan, not primarily national but transnational.

That was partly because European and American imperialism was itself a preeminently international system. Through the long centuries of its existence, it brought into being a profoundly unequal legal, economic, and political global order, based in part on the invention of racial hierarchies. Whatever the exact mechanisms of control, the ultimate purpose of colonial territories and their indigenous populations was always to sustain the power and status of their colonizers’ homelands and wider empires. And whenever Western powers collaborated to create new systems of international law, they perpetuated such inequities.

For example, Woodrow Wilson, the great champion of the new League of Nations after World War I, is often portrayed as having been motivated by an egalitarian, essentially anti-imperial conception of national self-determination. But as Adom Getachew argues in her astute and incisive first book, Worldmaking After Empire, that is pretty much the opposite of the truth.

In Wilson’s eyes, preserving “white supremacy on this planet” was the ultimate postwar goal. Just as African-Americans were unworthy of national citizenship, so, too, for colonized and other lesser peoples across the world self-government was not a right but a stage of development for which they were inherently unfit or, at best, woefully underprepared. After 1917 the Bolsheviks and their allies had put forward “self-determination” as a revolutionary, anti-imperialist principle, inviting colonized peoples to cast off their bondage. To forestall this challenge, Wilson and his collaborator, the Afrikaner statesman Jan Smuts, appropriated the term, but recast it as a racialized ideal that justified imperial rule as a permanent feature of the international order.

The League’s aims and mechanisms were explicitly modeled on those of the British Empire. Its definitions of nationhood were hierarchical and based on notions of differential development. A new system of “mandates,” whereby the former territories of the German and Ottoman Empires were divided up between the victorious Allies, perpetuated the principle of imperial tutelage for backward “native” populations (the acquiescence of their local rulers being enough to signify their self-determination). Though Liberia and Ethiopia were nominally full members of the League, their governments were treated as inferior and subjected to repeated racist and hypocritical “humanitarian” interventions—setting the stage for Italy’s invasion and annexation of Ethiopia in the autumn of 1935, and the other imperial powers’ endorsement of its colonization.

After 1945, even though formal European empires were gradually dissolved, the hegemony of imperialist systems of global economic and political dominance did not end, nor was it meant to. That was what the transition from empire to “commonwealth” was all about, as far as the British were concerned, even when it was forced upon them by anticolonial resistance. (This was why it was so maddening that Churchill refused to accept the inevitability of any kind of postwar “Indian self-government,” Amery confided to his diary in 1943: “I tried to suggest that modern nationalism in the East could not be met with mere resistance and that by giving way on the form we could maintain much of the substance, by treaty and otherwise, but he just refused to continue the discussion.”)

Worldmaking After Empire shows how black Anglophone anticolonialists on both sides of the Atlantic responded to this reality in the early decades of decolonization. In order to achieve true self-determination, they believed, it was not enough simply to free people from alien rule. Their full liberation from external domination, both economic and political, would also require a radical reconstitution of the international order. Decolonization had to be a project of worldmaking as well as nation-making.

The book focuses mainly on a loosely connected group of seven figures: the pathbreaking American activist W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the earliest and most influential black critics of imperialism; the African statesmen Nnamdi Azikiwe, Kwame Nkrumah, and Julius Nyerere; and the West Indian leaders and thinkers Eric Williams, George Padmore, and Michael Manley. As Getachew emphasizes, their visions were part of a much broader political tradition. International solidarity against imperialism had been central to socialist and Communist activism since the late nineteenth century, and many other transnational movements flourished across the decolonizing postwar world: Pan-Africanism, Francophone internationalism, the Non-Aligned Movement. But one distinctive feature of her subjects’ thought was its stress on how centuries of Atlantic slavery and forced labor had been fundamental in creating the modern international order: imperialism itself, they argued, was a global form of hierarchical, racialized bondage.

The older members of this group, like Williams, had been radicalized by the treatment of Ethiopia in the 1930s, and they viewed the foundation of the United Nations in 1945 as a dispiriting continuation of the status quo. The new organization’s charter paid only lip service to self-determination, the Nigerian nationalist Azikiwe noted in dismay: “Colonialism and economic enslavement of the Negro are to be maintained.” “We have conquered Germany,” agreed Du Bois, “but not their ideas. We still believe in white supremacy, keeping Negroes in their place and lying about democracy when we mean imperial control of 750 millions of human beings in colonies.”

Each of Getachew’s three brisk yet richly detailed central chapters describes a particular project of anticolonial worldmaking that sought to overcome these structures of domination. The first was the long and ultimately successful postwar campaign to transform self-determination from a vague principle to a firm legal right, and to convert the UN General Assembly into a platform for advancing decolonization. In 1960, despite the resistance of the United States, Britain, France, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, and South Africa, UN Resolution 1514, “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples,” established that “the subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation constitutes a denial of fundamental human rights” and was contrary to the UN Charter. Despite its specification of “alien” rule, which seemed to exculpate settler colonialism, this was a legal watershed. Here, and throughout the book, Getachew’s analysis brilliantly reveals how legal and political changes that conventionally have been interpreted as the natural, inevitable extension of preexisting Western ideals were only achieved, in the face of deep opposition, through the innovative (and historically contingent) efforts of non-Westerners. Internationally and domestically, decolonization was never freely granted by the powerful: it had always to be wrested from them by their subalterns.

Changing international law was only meant to be a beginning. But as the book’s two other case studies illustrate, the efforts of black Atlantic anticolonialists to create a more egalitarian global political and economic order were less practically successful. In both the West Indies and Africa, the postcolonial leaders of the 1950s and 1960s created regional federations to enhance the international clout of their new nation-states and enable them to gradually escape what Nkrumah described as a “neocolonial” trap, in which an imperial power, despite losing direct political control, “retained and extended its economic grip” over formerly colonized territories. Even more ambitious, but also abortive, was the push in the 1960s and 1970s for a “New International Economic Order.” Among other reforms, this would have given the UN’s General Assembly the power to mandate an equitable rebalancing of the world’s wealth and trading conditions toward the nations of the global South, whose workers and natural resources had for centuries been so ruthlessly exploited by the countries of the North.

Getachew is clearsighted both about the intellectual and political limitations of these schemes and the reasons for their eventual failure, though she could have said more about how the USSR and China fostered anticolonial movements, and the overarching dynamics of the cold war in shaping them. But her achievement is not just to have illuminated a set of postcolonial ambitions that came to an end in the mid-1970s. It is to have restored an important dimension of what decolonization stood for at its inception and can still aspire to in the present: the forging of a more just and equal international legal, economic, and political order. As each of these impressive, urgent books reminds us, to envisage a better future, we must start by looking properly at the past.