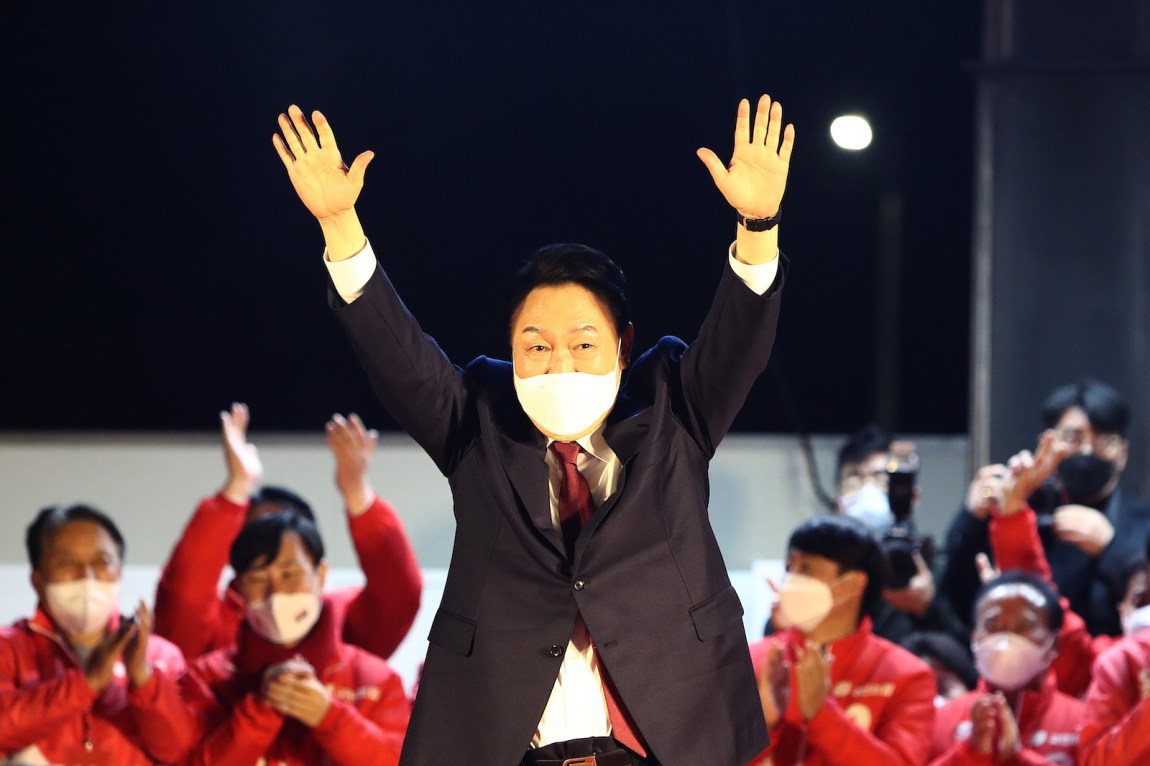

It is tempting to compare Yoon Suk-yeol, the career prosecutor who was elected president of South Korea last week, to former US president Donald Trump. There’s his lack of political experience, his flip-flop from one party to another, his questionable acquisition of familial wealth, his misogyny, his distaste for the poor and appeals to the rich—even his hairstyle.

Yoon is unlike Trump in one regard: he won the popular vote, albeit by only 247,000 ballots in a country of 52 million. The South Korean system is first past the post, so the margin does not matter. Yoon’s conservative People Power Party won 48.56 percent, while the other major candidate, Lee Jae-myung of outgoing president Moon Jae-in’s liberal Minjoo Democratic Party, garnered 47.83 percent. Shim Sang-jung, the formidable woman leader of the progressive Justice Party, received just 2.4 percent. (Moon did not run for reelection, as Korean presidents can serve only a single five-year term.)

Both Yoon and Lee came from outside the mainstream of their parties. Yoon was a “corruption-busting” prosecutor, trying former presidents and the head of Samsung under the Moon administration, before he switched parties and decided to run for president. Lee was a human rights attorney with a rags-to-riches backstory before becoming the mayor of Seongnam city and the governor of Gyeonggi province; he also ran unsuccessfully against Moon in 2017 for the Minjoo Party’s presidential nomination. Over the past few months, Yoon and Lee polled equally well—or poorly, rather. They were so well matched in their unpopularity that a blundered speech or a scandalous tidbit in the news would unsettle the race by a percentage point in either man’s direction. Yoon threatened a preemptive strike on North Korea. Lee admitted to plagiarism on his graduate-school thesis. Yoon’s wife lied on her résumé and sought counsel from a shaman. Lee’s wife used public funds on personal errands when her husband was governor. Yoon accused Lee of taking bribes from real estate developers. Lee accused Yoon of making politically motivated decisions as a prosecutor.

It was sometimes difficult to ascertain what each candidate stood for or divine what really mattered to South Korean voters. The things we Americans assume to be important to South Koreans—North Korea policy, relations with China and Japan, and the response to the pandemic—were hardly discussed on the campaign trail. When they did come up, Yoon gave no specifics but styled himself as a stereotypical conservative: cozy with Japan and the US, hostile toward China and North Korea, and unenthusiastic about health and social services. He would be the strongman Moon refused to be.

This much was clear: the race reflected a panic over inequality and lack of class mobility. In land-starved South Korea, people measure their futures against the price of high-rise real estate in Seoul, the capital city and home to one fifth of the population. But a Seoul apartment is now unattainable for ordinary workers, let alone those just starting out. (The rich, meanwhile, watch their assets appreciate and complain about marginal tax rates.) When Moon became president in 2017, after months of mass protests led to the impeachment of his predecessor, Park Geun-hye, the daughter of the military dictator Park Chung-hee, he promised an inclusive, compassionate politics. Moon pledged to tame condominium prices and real estate speculation, raise the minimum wage, and reduce the power of the chaebol mega-conglomerates once and for all. He did manage to lift the hourly wage by more than 40 percent and regulate development, but the cost of apartments continued to grow. The perception remained that the economy was fundamentally defective and that Moon was at fault, a wrongheaded but perhaps inevitable sentiment in a small, centralized nation.

The anxiety over housing and jobs became stuck in cultural grooves. Young men adopted a narrative that women, especially those who identify as feminists, are the cause of their downward mobility. The conservative opposition party seized on this turd of disaffection and polished it into an agenda, despite the pressures of fact: South Korea has the worst gender pay gap among all OECD countries and ranks consistently last in The Economist’s index of equal treatment at work; there are high rates of femicide and domestic violence. Yoon pandered to young male voters by declaring that sexism was imagined and vowing to eliminate the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. On the campaign trail, he donned fatigues and visited South Korean soldiers along the Demilitarized Zone, as if to bolster his own masculine bona fides. The tactics paid off: nearly 60 percent of men in their twenties voted for Yoon. A corresponding share of women in their twenties voted instead for Lee, but the margins were less pronounced in other age groups. Not so long ago, this kind of split was unimaginable: in South Korea, as is common elsewhere, young people generally vote liberal; older people, conservative.

Advertisement

Lee Jae-myung did not market himself as a chauvinist, but neither did he offer an alternative platform. For the past fifteen years, Korean progressives—the women’s movement, queer activists, disability-rights advocates, and ethnic minority groups—have focused on passing a national antidiscrimination law. But the evangelical Christian lobby, which is as large and politically connected as it is in the US, has obstructed their efforts. Lee might have grown his base by joining Shim of the Justice Party in backing the antidiscrimination campaign. Instead, after consulting with church groups, he renounced such legislation. A month before the election, Lee hired Park Ji-hyun, a prominent feminist activist, to consult on his campaign. But her intercession wasn’t enough.

I was living in South Korea between November and February, and found the mood among liberals and on the left to be despairing. Labor unionists were fed up with Moon, whom they saw as having ignored the poor and working class. Peace activists were angry with him for agreeing to US demands to install a missile defense system in South Korea and pay more to host American troops while failing to improve relations with North Korea. Many of these people had lost hope in the Minjoo Party, but they still planned to vote for Lee. To vote for Yoon, whose prosecutorial background contained an echo of the country’s dictatorships, was unthinkable.

Feminist friends, too, told me that they disliked their choices. Some would vote for Shim or cast an empty ballot. Some would vote reluctantly for Lee as a strike against Yoon. Just after the election, a twenty-year-old voter named Kim Yu-seon told a Hankyoreh newspaper reporter that Yoon and his People Power Party “reminded me of how former US president Trump used populist pledges and statements to win the support of white men.” In the hours after Yoon’s victory, Shim’s Justice Party received nearly $1 million in donations. Shim interpreted these sums as gestures of contrition from progressives who’d felt obligated to vote for Lee. “There are countless people who wanted to vote ‘Shim Sang-jeong,’” she said in her concession speech, “but swallowed their tears and changed their pick because the election was so close.”

During the Trump years, many South Koreans were proud to stand apart from the global authoritarian tide. They watched carefully as the January 6 insurrection occurred in Washington D.C., and the US let thousands die from Covid-19. Now, they’re wondering what happened at home. In exit polls, one in four people who voted for Moon Jae-in in 2017 said that they went with Yoon—a phenomenon not unlike the several million Obama voters who later supported Trump. Since 2016, observers have tried to explain the conversion of these Americans in material terms: that the Democratic Party had neglected to address kitchen-table economics, while the Republicans catered sincerely to the rich with tax cuts and corporate subsidies, and cynically to the working poor with culture wars and bootstrap rhetoric. The Minjoo Party must now figure out if some similar explanation applies to South Korea as well.

The People Power Party has no uncertainty about its base. In populous Seoul, which a candidate must take to win overall, the wealthier the neighborhood, the greater its support for Yoon. His promises of tax cuts and unbridled real estate development successfully charmed the chaebol class—those who live in the luxury condominiums. And his masculinist platform soothed many other Koreans who aspire, however unrealistically, to become their neighbors. Since last week, Yoon has formed a transition team that roughly corresponds to the many ministries of the executive branch. But there is no one dedicated to gender equality or inter-Korean peace. Yoon also did away with President Moon’s custom of reserving 30 percent of cabinet positions for women. “In the past, structural discrimination based on gender was real,” the president-elect explained. “From now on, it’s all individual.”