For weeks after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney remained closeted away in various undisclosed locations while Bush administration officials announced the start of a global war on terror. Cheney, the chief architect of that war, finally resurfaced in his office in the West Wing of the White House, where Bob Woodward of The Washington Post asked him how long the war might last. Cheney was forthright: “It may never end. At least, not in our lifetime.” It was the closest any public figure has come to predicting endless war—the dream of every militarist from Clausewitz and Moltke to Cheney and his fellow Vulcans in the Bush White House.

Cheney’s confident expectations have been borne out by events. Despite the recent pullout from Afghanistan, the war on terror has only spread in new technological and political forms. Attempts at regime change in Iraq, Libya, and Syria (as well as Afghanistan) have leveled ancient cities, destroyed hundreds of thousands of innocent lives, provoked resistance from multiplying jihadist organizations, and unleashed conflict across the Middle East and into South Asia and Africa. The inflation of a diffuse but permanent threat has created a vast new revenue stream for vendors of military hardware and a new industry of “counterterrorism consultants” whose offices line the highway from Washington to Dulles Airport.

Ostensibly constrained by rules that ensure humane conduct, the war on terror is unrelenting and everywhere, thanks in part to the embrace of drone warfare by Barack Obama, the constitutional lawyer who some of us thought was going to deliver us from the Bush administration’s violation of the Eighth Amendment along with other assaults on the Constitution. Instead, Obama became the assassin in chief while his lawyers made the war look a little cleaner. They also expanded the concept of self-defense to justify violating the sovereignty of any nation whenever it could be alleged to harbor terrorists. After September 11 no politician asked whether the proper response to a terrorist attack should be a US war or an international police action. Alternatives to war have remained unarticulated.

The war on terror seduced some of its critics, including Donald Trump, who like Obama had posed as an antiwar candidate. Trump, too, found the role of chief assassin impossible to resist. Yet even that clownish bungler so traumatized the national security establishment by hinting at a less aggressive posture that neoconservative Republicans and neoliberal Democrats came together to reassert their common interventionist commitments. Despite small dissensions, these abide in the current Congress.

Our public discourse, where not hopelessly fractured, has been focused on urgent and immediate issues of domestic politics and climate change. Intelligent discussion of foreign policy is increasingly unlikely, especially the issue of when and why the US should go to war.

The roots of this failure are entwined with Americans’ sense of themselves and their relations with the world, as Samuel Moyn shows in Humane, his brilliant new book. Moyn concentrates on the campaigns in Europe and the United States to make war more humane, from the creation of an international brigade (later known as the Red Cross) to care for the wounded in the Franco-Austrian War in 1859, to the legal constraints gradually imposed on the war on terror in our own time, when, as he writes, “swords have not been beaten into plowshares. They have been melted down for drones.”

Moyn’s central insight is that the quest for humane war, whether by deploying smarter weaponry or making new rules, has obscured the more basic task of opposing war itself: “Increasingly we live without antiwar law. We fight war crimes but have forgotten the crime of war.” In tracing the efforts to humanize war, Moyn casts new light on much of the surrounding historical landscape—not only peace movements and the divisions within them but also the assumptions of the warmakers themselves.

Humane provides a powerful intellectual history of the American way of war. It is a bold departure from decades of historiography dominated by interventionist bromides. A vainglorious narrative of modern US diplomatic and military history is embedded in our conventional wisdom: a struggle between prescient “internationalists” and ostrichlike “isolationists,” until the shock of Pearl Harbor awakens the reluctant giant to the responsibilities of global leadership, first in World War II, then in the cold war. (The Soviet Union’s crucial role in defeating Hitler is omitted.) US ascendancy is complete, in this view, with the collapse of Soviet communism and the rise of a unipolar world order in the 1990s. But there the upbeat story ends: even the most committed triumphalist finds it difficult to assimilate the troubling denouement of the September 11 attacks and the permanent state of emergency that followed.

Moyn probes the legal and ethical issues surrounding the war on terror, but he also assays the century and a half of US history that preceded it. The notion of humane war would have been alien and baffling to most Americans for much of that period. “America’s default way of war—honed in the imperial encounter with native peoples and lasting into the twentieth century across the globe—recognized no limits,” Moyn writes. He records the consequences in sobering detail, ranging from the extermination of Native American tribes to the torching of Vietnamese villages. During the Pax Americana following World War II the whole world, in effect, became “Indian country” (as many GIs referred to Vietnam).

Advertisement

But his most original and incisive contribution to historical understanding is taking seriously the possibility of peace—or at least the avoidance of war—as a primary goal of foreign policy. This leads him to dispute, for instance, the frequent dismissal of isolationists as shortsighted or xenophobic rather than people of good faith with an attachment to traditional American ideas of neutrality and a principled aversion to war. Moyn is neither a pacifist nor an isolationist, but he believes war must always be the genuine last resort, not merely the rhetorical one.

That perspective has been absent from foreign policy debates in recent decades. In Moyn’s view the reason is straightforward. Debating torture or other abuses, while indisputably valuable, has diverted Americans from “deliberating on the deeper choice they were making to ignore constraints on starting war in the first place.” Prohibiting torture and preventing war are both moral necessities, but war itself causes far more suffering than violations of its rules. It is a fatal mistake, says Moyn, to give up on the possibility of stopping wars before or even after they start.

The case is forceful, but Moyn sometimes suggests that we must choose between making war more humane and opposing it altogether. Though he denies that stark duality, he does not repudiate it consistently or explicitly enough. He occasionally implies that certain individuals made the wrong choice—people like Michael Ratner of the Center for Constitutional Rights, for example, who eventually shifted his attention from opposing the war on terror to reforming its abuses. There is a misplaced precision in Moyn’s critique that may be unfair to Ratner and other people in public life by exaggerating the choices available to them.

Moyn convincingly documents how the disappearance of peace as a topic for public debate correlates with the rise of arguments for humane war. But he doesn’t show specifically how one development relates to the other. We indeed need to talk more about whether we should go to war as well as how to stop it, but the shift toward humanizing is not the only reason we have failed to have that discussion.

The national reluctance to scrutinize the aims of war reflects the aura of sanctity surrounding them. For well over a century American warmakers tried to hallow military ambition with moral significance. With the fall of the Soviet Union, policymakers’ realization that the US was “the world’s only superpower” encouraged them to make even more grandiose assertions of righteousness. Humanitarianism became the default justification for US military action abroad—including the war on terror, which was billed in part as a crusade to save Muslim women and democratize the Middle East. To live up to their moral pretenses, military interventions had to be conducted humanely as well, reinforcing claims for the humanitarian purpose of the conflict and drawing public attention away from other motives.

A major one, often exposed by muckrakers but rarely mentioned by policymakers, is economic. Wars make a lot of people very rich. Moyn mentions this issue just once in passing, but it is difficult to overestimate its importance. When the cold war ended in 1991, an army of lobbyists remained in Washington to urge the continuation of enormous defense budgets. The claim that the new military goal was to rescue innocent victims abroad provided a moral gloss for sustaining spending at cold war levels. Humanitarian war could be good business, as has long been evident in the balance sheets of weapons vendors as well as the bank accounts of military contractors and counterterrorism consultants. It also resonated with the exceptionalist faith that America was “the indispensable nation,” as Madeleine Albright, Bill Clinton’s secretary of state, announced; we were destined to have a redemptive part in global history.

While Moyn scants the economic question, he does recognize that the hubris of the world-savers deserves to be confronted. And that, he believes, is not going to happen as long as political conversation remains fixed on abuses of war rather than how to avoid or end it. Rebranding the war on terror as humane has buried the essential question: Why are we waging it at all?

Advertisement

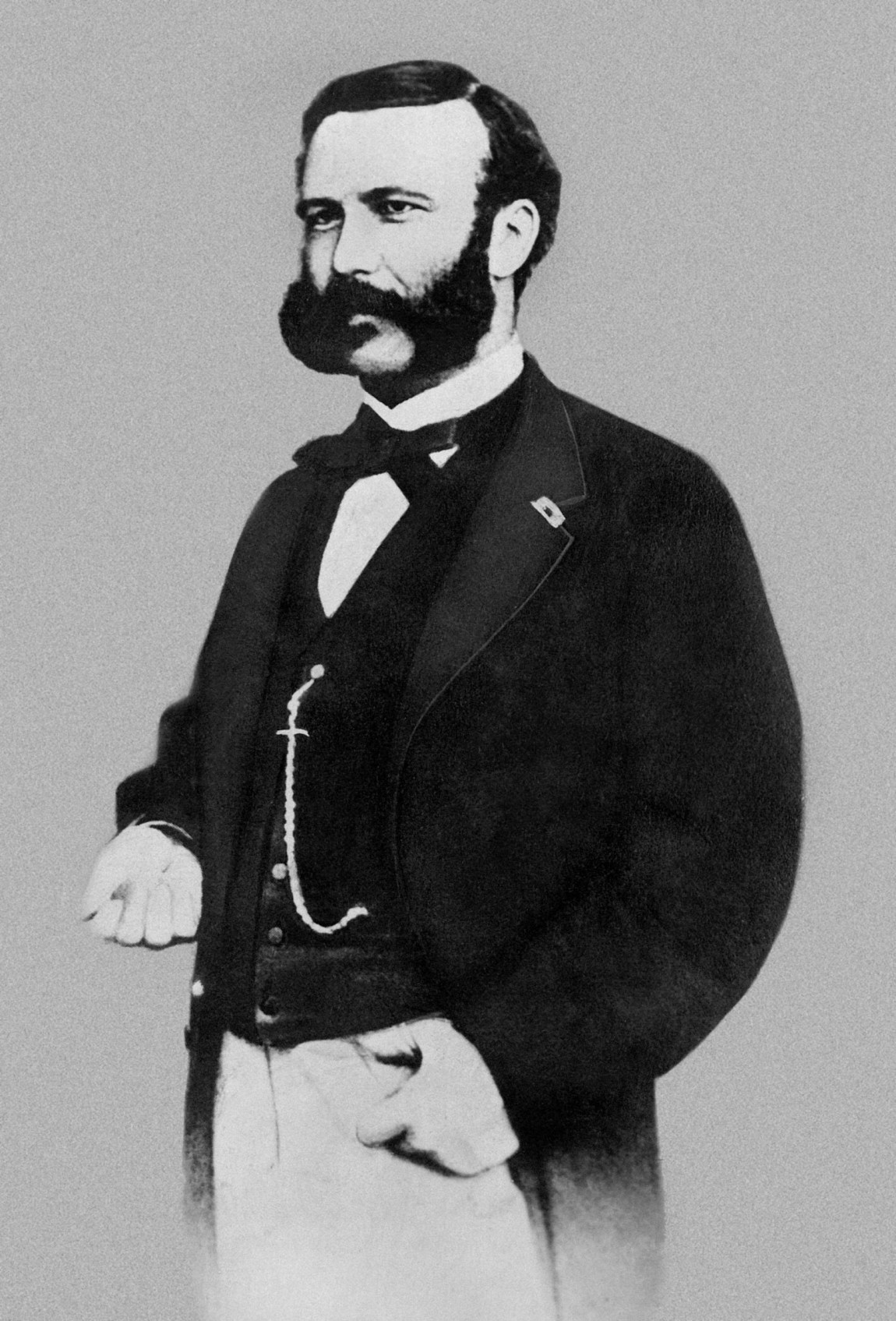

Moyn’s historical account begins with Henry Dunant, the Swiss gentleman who founded the Red Cross. Like most people in the 1860s, Dunant accepted war as an inevitable feature of the human condition, but he wanted the wounded to be cared for humanely. He won the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901. At that point he was an old man, and his handlers did their best to blur the boundaries between his advocacy of humane war and outright pacifism, which by then had become by far the more popular view.

Perhaps the chief force for legitimating pacifism was Bertha von Suttner’s novel of 1889, Lay Down Your Arms, which became the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the antiwar movement. Suddenly the dead and wounded were no longer faraway, faceless figures but “the husbands, sons, and brothers of modern women no longer resigned to their losses,” as Moyn writes. The book sold more than 200,000 copies in German, was translated into sixteen languages, and changed how people reflected on war and peace (Suttner herself won the Peace Prize in 1905). “For the first time,” Moyn observes, “the inevitability of war in human affairs was not taken for granted.”

Yet both the peace movement and the push to regulate war were mostly confined to hostilities among “civilized” white Christian nations. What few restrictions there were on whether and how wars were fought remained profoundly racialized. There were no prohibitions against mass murder of “uncivilized” people and no legal ways to constrain colonial wars, which took place within empires and therefore constituted internal, not international conflict—counterinsurgency combat against rebellious subjects.

For the United States, that meant killing and kidnapping the indigenous inhabitants of North America. The Civil War was an exception; the colonizers fought white people like themselves. The Union Army rules of war were based on the code of conduct devised by Francis Lieber, a Prussian émigré to America. Following Clausewitz’s dictum that brutal wars were best, the Lieber Code allowed anyone deemed a partisan to be shot on sight. Moyn might also have mentioned that the Civil War left 50,000 civilians dead, most of them Southern victims of the Union’s scorched-earth campaigns that laid waste to wide swaths of the countryside—Philip Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley campaign, William Tecumseh Sherman’s march from Atlanta to the sea. After the Southern surrender, such tactics were broadened and intensified in the mop-up operation against the Plains Indians. In 1873, when the Modoc leader Kintpuash, in California, tricked General Edward Canby into a meeting, then killed him, Sherman sanctioned the “utter extermination” of the Modoc tribe.

Exterminationist tactics worked well in imperial wars when one side possessed technological supremacy and the other was deemed less than human. When Adna Chaffee arrived in the Philippine Islands in 1901, fresh from putting down the Boxer Rebellion against “foreign devils” in China, he announced, “Murder is almost a natural instinct with the Asiatic, who respects only the power of might…. Human life all over the East is cheap.” This racism animated the suppression of Asian insurgencies from the Filipino uprising of the early 1900s to the Vietnam War.

The Great War brought new horrors to the fore—not only the spectacle of soldiers slaughtering one another at close range with modern weapons but new ways of inflicting pain on civilian populations. The “most gross moral wrongdoing” of the World War I era, Moyn believes, was not the German atrocities in Belgium but the British blockade of the Continent. It was entirely legal under international law and left half a million civilians dead from starvation, without arousing widespread humanitarian protest. This history needs to be remembered amid the current American obsession with economic sanctions as the humane alternative to military force. After the Versailles Treaty, the postwar peace movement flourished as never before; antiwar activists like the US political scientist Quincy Wright sought enduring structures of international arbitration, and others sought simply to outlaw war, as in the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928. Mere dreams, it turned out.

Militarists’ aspirations fared better. Among the most fantastic were those involving air war, which became a go-to gambit for pacifying anticolonial resistance across the globe. Gas bombs, a particular favorite of Winston Churchill, promised to perform “an almost bloodless surgery,” a British international lawyer said. The fantasy of surgical precision has survived down to the present, but not everyone cared about it. In 1927 the strategist Elbridge Colby, whose son William became director of the CIA, predicted a new age of total war where “there were no non-combatants.” That war arrived soon enough. After Pearl Harbor the American pursuit of global military supremacy “dealt as humbling a defeat to internationalist visions of peace through law, especially the dream of arbitration, as to ‘isolation,’” Moyn writes. From World War II forward, in much public discourse, “internationalism” became little more than a euphemism for a commitment to maintaining the Pax Americana.

On September 1, 1939, when the Germans began bombing unarmed civilians in Warsaw, they “shocked the conscience of humanity,” according to Franklin Roosevelt. By 1944 the Americans and the British were igniting firestorms in cities across Germany. One US officer worried that it would “convince the Germans that we are the barbarians they say we are.” The war in the Pacific was a race war for the Americans as the war in Europe was for the Germans. Even before the incineration of Japanese cities began, the GI skull collections and the nonchalant executions of civilians including women and children made it clear that the Pacific theater “was ‘Indian country’ all over again,” as Moyn observes. There were plenty of good reasons for The New York Times to conclude, in 1944, that war could not be made humane—“it can only be abolished.” The task was to end the dirty business in a way that ensured “no city shall ever be bombed again.”

What was astonishing was that anyone still thought that goal was reachable. During the run-up to the war, pacifism had been tarred with the brush of “appeasement” and almost vanished altogether during the fighting. Wright and other champions of arbitration nevertheless labored to keep international law involved in creating a peaceful postwar world. Peacemakers, they argued, had to create the means for identifying and punishing aggressors. This was the background to the Nuremberg trials—they put perpetrators on trial for starting an aggressive war, not for committing war crimes. War was the crime. There were attempts to protect civilians and prohibit torture in Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, but after the atomic bomb, as one international lawyer said, “the humanitarian Conventions read like hypocritical nonsense.”

Meanwhile the high purpose of the United Nations was redefined away from enforcing international law to implicitly ratifying the domination of the world by two rivalrous superpowers. If you were a permanent member of the Security Council, as both the US and USSR were (and the US and Russia of course are), you could veto any resolution that labeled you an aggressor. If you were a country that made the rules, then you could make a rules-based order work for you, as the US demonstrated by repeatedly violating the sovereignty of other nations—Iran, Guatemala, Congo, Chile…—throughout the cold war without ever being held to account.

One brief exception to this narrative of acquiescence was what Moyn calls “a period of clarity in the early 1970s, when many people, far more than ever since, were prepared to see government officials and US citizens themselves as potential and actual evildoers.” People were not uniquely virtuous, in other words, merely because they were Americans. In “that crystalline moment of insight,” doubts about how US soldiers conducted themselves in Vietnam were linked to larger disagreements about whether they should be there at all, as well as an even larger skepticism about whether and when (if ever) foreign wars served US interests. Peace was briefly seen as a legitimate policy goal.

This became apparent when the uncovering of the My Lai massacre intensified demands to end the US presence in Vietnam and not merely to reform military practice. Critics of the war saw the incident as a natural consequence of the joint US–South Vietnamese military strategy that included bombing the North Vietnamese “back to the Stone Age,” as General Curtis LeMay recommended; torturing and killing prisoners; imprisoning political opponents of the South Vietnamese government in “tiger cages”; and assassinating civilians suspected of Viet Cong sympathies. Invoking rules of war or international law amid such systematic violations seemed grotesquely inadequate. For antiwar activists, from the legal scholar Richard Falk to Martin Luther King Jr., the war itself, as Falk put it, was “an all-embracing war crime.”

But that “crystalline moment” soon ended. After the Vietnam debacle, antiwar sentiments softened and slid toward civilizing the methods of fighting. Telford Taylor, counsel for the prosecution at Nuremberg, provided historical legitimacy in Nuremberg and Vietnam (1970) by framing the trials as a judgment against atrocities, not aggression. This was a fallacious reinterpretation, in Moyn’s view, but it created a heroic lineage for humane war. At about the same time, the Swiss jurist Jean Pictet was conjuring what he called “international humanitarian law” by drafting two additional protocols to the Geneva Conventions—militaries were prohibited from targeting civilians and indeed anything that risked excessive collateral damage. (The US has signed and ratified the conventions but failed to ratify the protocols.)

During the 1980s, as Reagan embarked on imperial adventures in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, various human rights groups were formed in response. Helsinki Watch created Americas Watch, which later became Human Rights Watch, led by Kenneth Roth. “We weren’t against war per se,” Roth recalled. It was, says Moyn, a “reasonable position,” but he wonders “what was the effect of demanding humane war if there were fewer and fewer left demanding no war?”

The answer would come shortly. In 1991, after the brisk and painless (for Americans) victory in the first Gulf War, the Washington establishment was euphoric. As President Bush the first said, “The specter of Vietnam has been buried forever in the desert sands.” Prior talk of a “peace dividend” from the conclusion of the cold war subsided. Overseas military actions multiplied. As Moyn reports, “More than 80 percent of all US military interventions abroad since 1946 came after 1989.”

In seeking to understand this extraordinary statistic, he poses a series of questions. Were the multiplying interventions due to “the accumulating dangers of a globalizing world?” Or was it the illusion of quick entrances and exits in the Middle East created by the apparent ease of victory in the Gulf? Subsequent experience suggests the latter surmise is closer to the truth. To which Moyn adds a third, equally provocative: “Or was it perhaps the pressure of a ‘military-industrial’ complex that insisted on fighting enemies (albeit more humanely now) to justify its perpetuation?” This is the only place where he mentions the ever-present influence of the civilian army that exists in symbiosis with the military one—the swarm of lobbyists, corporate profiteers, contractors, and consultants who help to sustain endless war. His neglect of the subject is puzzling: the billions of dollars to be made should inform any foreign policy debate. But try to find any sustained discussion of it in The New York Times or The Washington Post.

Bill Clinton came to the presidency at the unipolar moment, just after the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991. It was a propitious time for imperial expansion in the name of universal values. Even as the Warsaw Pact disbanded and the justification for NATO collapsed, Clinton began the policy that Bush the second continued—the eastward advance of NATO, which seasoned observers from George Kennan to Henry Kissinger to William Burns all warned would provoke Russian security concerns.* (Recent events have demonstrated their prescience.) While Albright and her colleagues itched to put their “superb military” to work, proponents of putatively benign intervention abroad offered opportunities.

Post–cold war humanitarian thought put the Holocaust at the moral center of World War II, a move reinforced by the recasting of Nuremberg as anti-atrocity rather than anti-aggression. “The result was not a demand for peace but for interventionist justice,” Moyn observes. The justice could even be preemptive, if catastrophe seemed to loom for a victimized population. As conflict in the Balkans raised the prospect of ethnic cleansing and potential genocide, interventionists summoned Holocaust memories to prod Clinton into action. Eventually the US led the NATO bombing of Serbia to prevent threatened mass killings in Kosovo. The absence of UN Security Council authorization made the incursion illegal, but Clinton defended it as a “just and necessary war.” By and large, the press and the intelligentsia agreed. It is not clear whether Moyn thinks the intervention actually prevented genocide—which remains a matter for conjecture. For him, the Balkan wars reinforced a new consensus that later encouraged acceptance of a war on terror and reserved criticism only for its cruelties.

Not everyone was so accepting. When George W. Bush announced his intent to use military commissions to try suspected terrorists, Michael Ratner pronounced the policy “the death knell for democracy in this country.” Ultimately his critique was upheld by the Supreme Court, which ruled that Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions forbade Bush’s military commissions and that federal courts could issue writs of habeas corpus to end preventive detention.

Yet according to Moyn, Ratner and other shrewd critics of the war on terror were led into the “misguided strategy” of amending rather than ending war, as if the two positions were mutually exclusive. Why mightn’t Ratner simply have been trying to play the bad hand he had been dealt, adjusting to the ideological straitjacket that opponents of the war on terror had to wear during its early years? Ultimately his career seemed to show that a desire to ameliorate the effects of war can coexist with a consistently antiwar perspective.

The Center for Constitutional Rights, which Ratner led for much of his career, was, unlike Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, opposed to the first Gulf War and the war in Serbia, not merely the conduct of them. Ratner and his colleague Jules Lobel attacked the malleability of humanitarian arguments for intervention head-on, observing that even Hitler insisted he had intervened “militarily in a sovereign state because of claimed human rights abuses.” The worst sort of war was likely to occur “when war-makers claimed uplifting reasons for embarking on it,” Moyn writes.

After the invasion of Afghanistan, however, Ratner redirected his energies, now dealing exclusively with those sometimes innocent people who were swept up in the conflict, imprisoned, and tortured. With the revelations surrounding Abu Ghraib, objections to prisoner abuse began to seem more persuasive than abstract debates about the rights and wrongs of intervention. Restoring the taboo against torture, according to Moyn, meant that “no taboo was constructed containing the war itself.” But he does not explain why one taboo should necessarily supplant the other.

Obama accelerated the move toward “humane” war. Mistaken for a man of peace, he used his oratorical gifts to encourage his audiences to see whatever they hoped to see in him and ultimately saved the war on terror by sanitizing it. His lawyers built on the Bush administration’s legal sophistries, claiming the authority to extend war indefinitely, while he turned to battle plans that left no footprints (drones) or only light ones (special forces) and began “a spree of humane killing on which the sun might never set in space or end in time,” Moyn writes. This clean war on terror was as illegal as the dirty one had been.

However decorous the new tactics were perceived to be, they continued to violate international laws requiring both an imminent threat of armed attack and the consent of states where terrorists were allegedly located. CIA director John Brennan insisted there was no need to make a case for self-defense every time we struck at al-Qaeda. This presumed “an astonishing license to kill”—whether families or whole neighborhoods—and often to kill people who had never been near al-Qaeda and who had never attacked the US or posed a serious threat. The constant menace of drone strikes created a world of permanent dread.

At home, Obama succeeded in making war seem remote and detached from the messy business of body bags and bitterly contested occupation, largely by reasserting America’s singular virtue, underwritten by a renewed commitment to humane warmaking. “We” had “tortured some folks,” Obama allowed in a moment of television contrition, but, as Moyn puts it, we were “not the kind of people who would ever do so again.”

Until the current crisis in Ukraine, the most striking omission from foreign policy discourse has been the increasing risk of nuclear war—the kind that can never be made humane. Though few in the media seem to know it except The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the likelihood of nuclear war has risen to cold war heights, perhaps higher, for a variety of reasons, beginning with the ever-present possibility of accidental missile launch but also including the accelerated modernization of nuclear weapons (begun by Obama, continued by Trump) and the renewal of cold war–style confrontation with Russia, the world’s only other nuclear superpower—now escalating with terrifying speed in Ukraine, fueled by ignorant and irresponsible calls for a no-fly zone.

Moyn insists that preventing and ending war should be our primary foreign policy goals. Yet the US has failed to put a cease-fire and a neutral Ukraine at the forefront of its policy agenda there. Quite the contrary: it has dramatically increased the flow of weapons to Ukraine, which had already been deployed for eight years to suppress the separatist uprising in the Donbas. US policy prolongs the war and creates the likelihood of a protracted insurgency after a Russian victory, which seems probable at this writing. Meanwhile, the Biden administration has refused to address Russia’s fear of NATO encirclement. Sometimes we must conduct diplomacy with nations whose actions we deplore. How does one negotiate with any potential diplomatic partner while ignoring its security concerns? The answer, of course, is that one does not. Without serious American diplomacy, the Ukraine war, too, may well become endless.

-

*

See Fred Kaplan, “‘A Bridge Too Far,’” The New York Review, April 7, 2022. ↩