Princes shall come out of Egypt;

Psalm 68:31

Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God

Cowboy hat from Gucci

Lil Nas X

Wrangler on my booty

Can’t nobody tell me nothing

Of the many armored costumes black artists have worn in America, the pharaoh and the cowboy are perennial favorites. Who could forget Michael Jackson in the video for “Remember the Time,” shimmying before the pyramids to the delight of a Nefertiti-crowned Iman? Or Sun Ra in Space is the Place, wandering earth with his entourage of deities in a striped headdress? Ra, who exchanged his “slave name” for a divine moniker, famously declared that black Americans were “myths.” Yet even a sober sociologist like W. E. B. Du Bois wasn’t immune to Ancient Egyptian drag; in 1913, he staged an elaborate historical pageant that featured crowds of worshippers thronging a replica Sphinx. Langston Hughes captured the time-traveling allure of neo-Egyptian identity in his poem “The Negro”: “Under my hand the pyramids arose. / I made mortar for the Woolworth Building.”

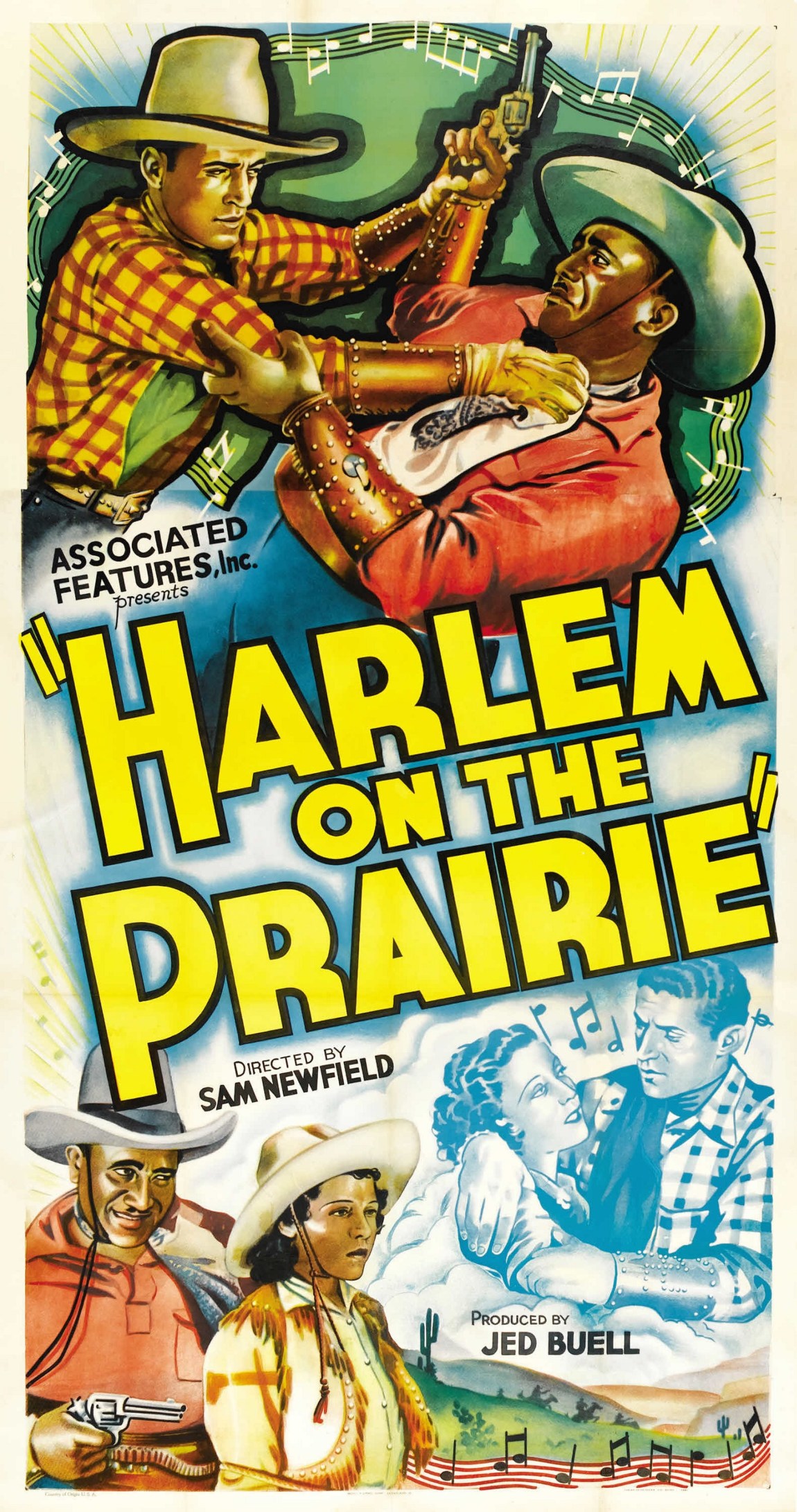

The black cowboy’s appeal is similarly venerable, starting with Nat Love, who rose from slavery to become a famous gunfighter and chronicler of the Old West, and continuing through a century of Hollywood movies, from Harlem on the Prairie (1937) to 2021’s action blockbuster The Harder They Fall. Both tropes offer iconic headgear and fantasies of racial empowerment. Yet they also point in opposite directions, one toward the collective reclamation of African heritage and the other toward entrepreneurial savvy in the free-for-all of American life. The Negro who Speaks of Rivers seemingly faces a decision: Nile or Rio Grande? Then again, it may have been inevitable that someone, eventually, would imagine a world where, to paraphrase scripture, “Cowboys shall come out of Egypt.”

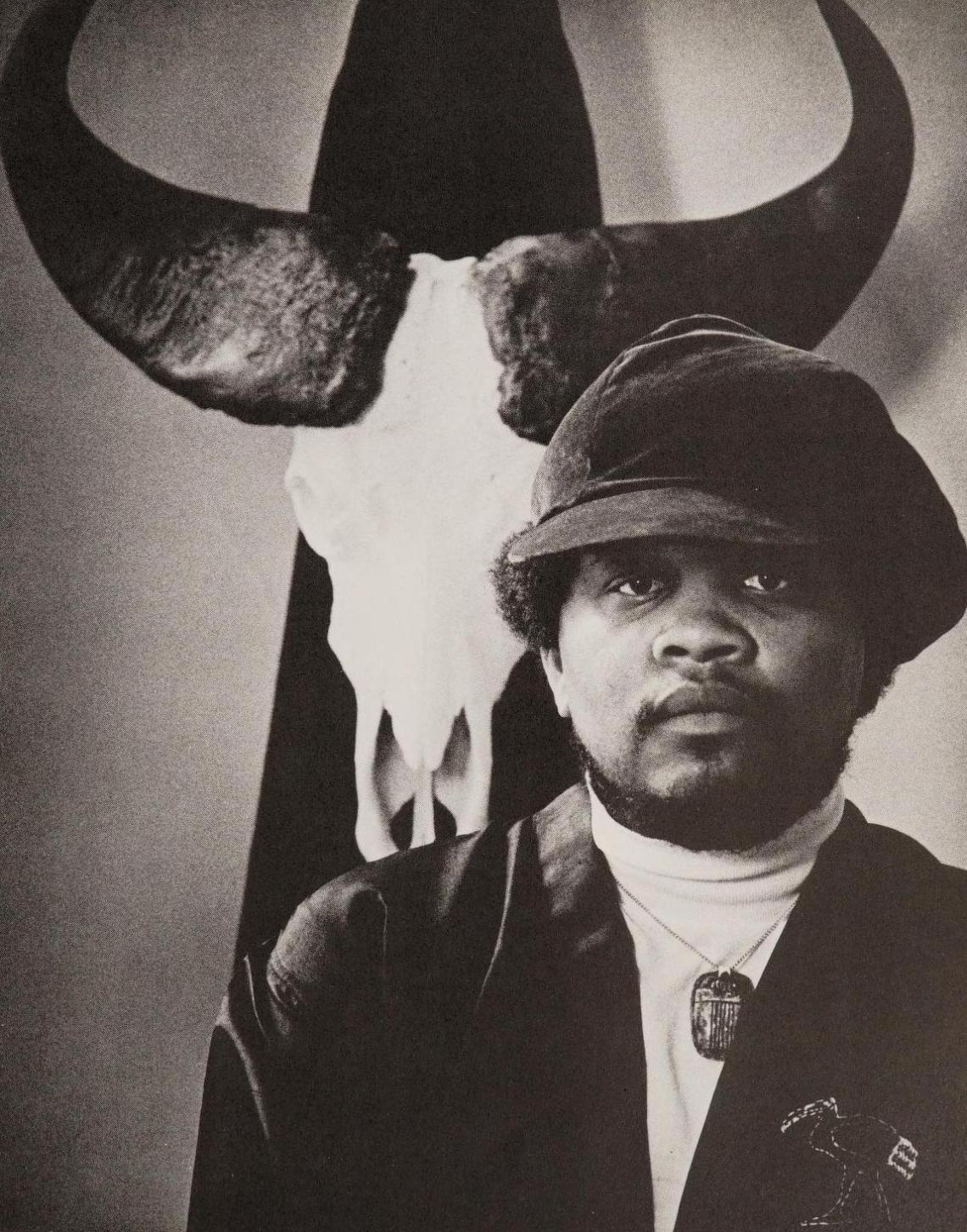

Ishmael Reed didn’t invent the black Western or the Afrocentric vogue for Ancient Egypt. But he may have been the first writer to synthesize their iconographies—a feat he accomplished, to great comic effect, in Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down. Published in 1969, Reed’s sophomore novel is a Western-style showdown over the origins of “Western” civilization. Its hero is the Loop Garoo Kid, “a desperado so onery he made the Pope cry,” who fights to liberate the frontier town of Yellow Back Radio from a malevolent cattle baron and his venal cronies. Their cartoonish strife draws inspiration from Egyptian mythology, skewering the mystique of the Old West through surreal pastiche and slapstick. In a 1972 interview with John O’Brien, founder of the Dalkey Archive Press, Reed described the novel as “artistic guerrilla warfare against the Historical Establishment.”

Reed began experimenting with the Egyptian cowboy in the mid-1960s, when he was a young poet living on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Dubbed the “godfather of Black postmodernism” by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., he was born in 1938 in Chattanooga and grew up in Buffalo, where he married young and worked as a hospital orderly. Determined to become a writer, he moved to New York City in 1962. There, he found fellow travelers in the Society of Umbra, an underground magazine and writers’ collective that decisively influenced the Black Arts Movement. Its members met weekly at the 2nd Street apartment of the group’s cofounder, New Orleans-born poet Tom Dent, where they workshopped poems and delved into African traditions from Caribbean obeah to the epics of Malian griots.

Ancient Egypt, too, was in the air. Reed met Sun Ra, who contributed to Umbra’s third issue, and befriended fellow workshop members Lorenzo Thomas, David Henderson, and Askia Touré. All five wrote poetry laced with allusions to “Kemet,” or “the black land,” as it was called in Old Egyptian—a reference to the Nile valley’s dark soil but also, for the poets of Umbra, an expression of racial pride. They liked to mix past and present. Henderson’s “Egyptian Book of the Dead” pictures a contemporary Harlem boy “bopping / into the garden of music / looking for isis.” Touré’s elegy for John Coltrane imagines the great saxophonist in the lineage of magi, who, “in pyramidal silence / made the JuJu in our blood outlast / the Frankenstein of the West.”

Reed wrote poems, now lost, about Thoth and Queen Hatshepsut, modeling his efforts after W. B. Yeats’s embrace of Irish folklore in the Celtic Revival. At the same time, he drew on a childhood love of Western Americana, from radio broadcasts of “The Lone Ranger” to the exploits of Jesse James. He combined the two worlds in “The Jackal-Headed Cowboy” (1967), which envisions an urban insurrection led by a mounted Egyptian deity with jangling spurs:

. . . fast draw Anubis, with his crank letters from Ra

will Gallop Gallop Gallop

our mummified profiled trail boss

as our swashbuckling storm fucking mob rides shot

gun for the moon and the whole sieged stage coach

of the world will heave and rock as we

bang stomp shuffle stampede cartwheel and cakewalk our

way into Limbo.

The poem diverges from the Egyptian verse of his peers in its rambunctious comedy, which transposes Anubis to a distinctly American vernacular—a sign of Reed’s increasingly confident style. Although Reed had joined Umbra as a “Malcolmite,” he’d become skeptical of black nationalism after the workshop’s partial breakup in 1963, which mirrored the widening split between Black Power and Civil Rights. Touré and several other members joined Amiri Baraka’s separatist-leaning Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem, but Reed objected to their flirtation with “Yacubism,” the Nation of Islam–derived belief that white people were inhuman creations of a malevolent scientist. He was equally opposed to what he saw as the devaluation of black American culture by militant worshippers of a stylized Africa. “Charlie Parker was born in Kansas City,” he snapped in one early interview, “not Lagos.” At the same time, Reed yearned for a revolutionary transformation of arts and letters in America, one that would exorcise racism, European aesthetic hierarchies, and the puritanical legacy of Christianity’s jealous god.

Advertisement

These impulses culminated in Neo-HooDoo, Reed’s signature idea that black arts, especially popular music, were shrewdly disguised continuations of African spiritual traditions. From the anthropological writings of Zora Neale Hurston and the paintings of his friend Joe Overstreet, he learned that the hybrid rites of diaspora faiths like Haitian Vodou could be models for defying Western monomania: one god, one culture, one canon, and one black writer at a time.1 Neo-HooDoo, by contrast, would imagine a world where “every man is an artist and every artist a priest,” as he wrote in the movement’s 1971 manifesto.

This breakthrough led to a streak of books that remain Reed’s most celebrated, especially the Harlem Renaissance–era detective novel Mumbo Jumbo (1972) and the neo–slave narrative Flight to Canada (1976)—both genre parodies with trickster heroes. Their prototype was the Loop Garoo Kid, who first appeared in the much-anthologized poem “I Am a Cowboy in the Boat of Ra” (1969):

I am a cowboy in the boat of Ra. Lord of the lash,

the Loup Garoo Kid. Half breed son of Pisces and

Aquarius. I hold the souls of men in my pot. I do

the dirty boogie with scorpions. I make the bulls

keep still and was the first swinger to grape the taste.

At a 1974 reading with Allen Ginsberg at the Library of Congress, Reed described the poem as a duel inspired by two cattle cultures. In Egyptian mythology, the god Horus feuds with his uncle Set, lord of the desert and frontiers, over the crown and royal cattle of the Pharaohs. Their strife extends from courtroom drama to open-air wrestling, and Reed, a master of anachronism, saw an opportunity: What could be more Western?2 His Loop Garoo Kid would also be a conjure man, a werewolf from Cajun folklore, and a worshipper of Judas Iscariot—the terror not only of the Old West but of Western Civilization. Drawing on contemporary arguments that Christianity had stolen and then demonized Egyptian theology, Reed’s poem ventriloquizes a black pagan bastard out to wrangle his inheritance:

bring me my Buffalo horn of black powder

bring me my headdress of black feathers

bring me my bones of Ju-Ju snake

go get my eyelids of red paint.

Hand me my shadow

I’m going into town after Set

I am a cowboy in the boat of Ra

look out Set here i come Set

to get Set to sunset Set

to unseat Set to Set down Set

usurper of the Royal couch

—imposter RAdio of Moses’ bush

party pooper O hater of dance

vampire outlaw of the milky way

The stage was set for a gunfight at the Old Kemetic Corral. In Yellow Back Radio, Set becomes Drag Gibson, a cattle rancher so vile and greedy that he spends each morning embracing his property—a ritual that includes French-kissing his sickly and terrified green horse. (The novel may in fact be a transcript of this horse’s nightmare.) Like all would-be gods in a mass-media society, Drag aspires to control the airwaves, win celebrity, and “va-va voom on to the East.” He is decadent American settler-colonialism incarnate; Loop Garoo, by contrast, represents another dream of the “West,” where the nation’s diverse peoples might finally realize their aesthetic and spiritual freedom. “Please do open up some of these prissy orthodox minds,” he implores the gods of his personal pantheon. “Show them that Booker T and the MGs, Etta James, Johnny Ace, and Bojangles tapdancing is just as beautiful as anything that happened anywhere else in the world.”

Loop Garoo is a consummate entertainer. He comes to Yellow Back Radio with a traveling circus to perform lasso tricks, only to find that local youths have overthrown their elders for making them fight “savages,” echoing resistance to the Vietnam War. They greet Loop’s troupe with the enthusiasm of counterculture kids turning out for Jimi Hendrix. Nobody realizes that Drag Gibson has invited the circus as cover for an ambush—an effort to exploit the power of art that, like many Reed villains, he will later regret. As the cattleman’s henchmen retake the town, Loop departs to prepare his revenge. It’s a vision of popular art as metaphysical warfare. As Reed told O’Brien, “American vaudeville is a serious mystery drama of civilization.”

Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down was, in many ways, Reed’s declaration of independence. It was the first book he wrote after moving to California in 1967—first Los Angeles, then Berkeley, and finally Oakland—an exit that he has often described as an escape. “If I had remained in New York, I would’ve been killed by an overdose of affection,” he’s said. Even before his debut, The Free-Lance Pallbearers, earned favorable comparisons to William S. Burroughs, he’d begun to fear that the white publishing world was grooming him to become their next token. It didn’t help that some of his revolutionary peers agreed. When Reed denounced the “goon squad aesthetics” of separatist nationalism in the Journal of Black Poetry, an editorial afterword excoriated him as a “remote control nigger” interested in “European concepts like dada” and “some jive about T.V.”

Reed struck back, as he often does, in fiction. Wandering the desert, Loop is accosted by a group of bandits led by Bo Shmo, a chicly dressed radical who heads a “neo-social realist Institution in the Mountains.” Shmo exploits guilty liberals to earn a living, mostly through robbing wagon trains of thrill-seeking sadomasochists from the east coast. He taunts Loop for being an “alienated individualist” whose books don’t make sense:

Crazy dada nigger that’s what you are. You are given to fantasy and are off in matters of detail. Far out esoteric bullshit is where you’re at. Why in those suffering books that I write about my old neighborhood and how hard it was every gumdrop machine is in place while your work is a blur and a doodle.

It’s a riff on the old saw that all black writing ought to be protest literature, and Loop responds with an anarchist credo that has remained one of the most quoted passages in Reed’s work:

What’s your beef with me Bo Shmo, what if I write circuses? No one says a novel has to be one thing. It can be anything it wants to be, a vaudeville show, the six o’clock news, the mumblings of wild men saddled by demons.

The rejoinder doubles as a defense of Reed’s freewheeling style. Written like a radio play—with unmarked dialogue and all-caps bursts of action—Yellow Back Radio is brazenly metafictional, mixing tropes and timelines with abandon. The year is ostensibly 1808, but “old Buicks and skeletons of washing machines” litter the desert, where the legendary Seven Cities of Cibola turn out to be automated subdivisions equipped with swimming pools and fast-food franchises. Generals denounce Thomas Jefferson as “a freaky bopper peacenik,” while Lewis and Clark make cameos as flatulent whoremongers coddled by their Native hosts. The roles of pagan “savage” and cosmopolitan settler are inverted: Loop Garoo’s Native ally, Chief Showcase, flies a helicopter and describes himself as a “patarealist.”

The novel’s spliced chronology has justly won Reed recognition as a pioneer of postmodern fiction and Afrofuturism. Yet he was also drawing on an older lineage of American experimentalists who mixed fantasy and folklore, particularly the Great Depression–era satirists Nathanael West and Vincent McHugh. Similarly, Reed’s approach to media criticism echoed early African-American writers like William Wells Brown and Charles Chesnutt, whose 1899 short story collection The Conjure Woman revolves around an elderly freedman adept at spinning supernatural tales to manipulate his white employers. For Reed, too, the metaphysics is the message. At the climax of Yellow Back Radio, Loop Garoo breaks into the local radio station. The bewitched host announces: “The demons of the old religion are becoming the Gods of the new.”

It is strongly implied that Loop Garoo is, among his many other aliases, the Biblical devil. We learn early that he has been kicked out of “the Attic” by “the old man,” and that his old girlfriend has left him to kiss the feet of a kinky demagogue who likes to show off his scars. The breakup is an allegory for the schism between Christianity and its pagan predecessors. While writing the novel, Reed was studying Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” which consigns Egyptian deities like Isis, Horus, and Osiris to the fires of Pandemonium. Reed’s novel attempts to repair this metaphysical injustice, following Zora Neale Hurston’s observation that in black folklore, the devil is not evil but “a powerful trickster who often competes successfully with God.”

Loop Garoo is not just the repressed pagan “Other” of Western Christianity, a Kemetic answer to John Wayne and Jesus. Although the character began, in poetry, as an Egyptian deity, Reed’s novel shifts the emphasis to African-American spirituality. In a definitive moment for Reed’s Neo-HooDoo, the African god–cum–American cowboy evolves into the priest of a distinctively New World religion, as Loop Garoo summons the Loa spirits of Haiti and Louisiana to curse Drag Gibson with “the retroactive itch.” He invokes not only established deities but also twentieth-century African-Americans, from the boxer Jack Johnson to a man named “Mack Hopson”—an allusion to Reed’s maternal grandfather in Tennessee. The ceremony ends with a plea: “if I am not performing these rites correctly send the Loa anyway and allow my imagination to fill the gaps.”

Like many great breakthroughs, Yellow Back Radio is the work of an artist in development. Loop Garoo’s caveat is partially an emerging writer’s nod to his incomplete mastery of his subject: Reed, who engaged with African religious traditions more robustly in later novels, has called his early experiments with Vodou “touristic.” But as the scholar Glenda Carpio has noted, his use of Vodou also “intentionally dispenses with the notion of authenticity,” affirming the need to improvise in the gaps of a heritage that violence has fragmented and erased. She reads his novels as rituals of redress that comically take possession of their genres, much as the divine horsemen, as the loa are called, mount their worshippers.

Satirists, like deities, risk taking on the flaws of their vessels. Reed came to regret Loop Garoo’s libertarian affinity for Thomas Jefferson. Years later, during his famous campaign against Lin-Manuel Miranda’s popular Broadway musical Hamilton, he brought it up as an example of his own youthful susceptibility to Founding Father propaganda. More difficult for a contemporary reader to ignore are the novel’s sexual politics. Its minor villains include prostitutes with names like Mustache Sal and Mighty Dyke, “a bulldyker octoroon” who wears a belt of plaster-of-Paris penises. Its white male heavy, the flamboyantly dressed rancher named Drag Gibson, wears mascara, kills his wives, and boasts of his “barnyard overflowing with robust and erotic fowl.” (Drag explicitly refers to the cowpoke who rides at the back of the herd, but the double entendre is obvious.)

Astute critics like Michele Wallace and Margo Jefferson have seen more than a little chauvinism in Reed’s caricatures. In 1986, Wallace argued that its source was Neo-HooDoo’s “basis in religion, which has been laying its eggs of phallocentrism wherever it goes at least since Egyptians had a choice between the worship of Osiris and Isis.” It’s true that, following his mythological sources, Reed’s novel sets a heroic masculine avenger against a rogue’s gallery of wayward women and sexual deviants. And Loop, who is once referred to as a “pimp,” smacks bitches like any blaxploitation stud; in a sex scene, he uses a hot iron to brand a contrite ex-lover (who left him for Jesus) as she moans in ecstasy: “O Loop my mitt man. How I missed your good good loving.”

Wallace’s critique was reinforced by Reed’s well-publicized skirmishes with the feminist movement. Even so, she may have overlooked the anti-patriarchal undercurrents of his bawdy spiritualized satire. Perhaps Reed did too. Vodou, after all, is known for its acceptance of women, gay men, and nonbinary practitioners, as well as its emphasis on the continuity of body and mind. Spirits like Guede, lord of the dead, use comedy and eroticism to mock the pretensions of mortal patriarchy—a divine laughter that Reed links to the medieval tradition of carnival. Its great theorist, Mikhail Bakhtin, wrote that “certain essential aspects of the world are accessible only to laughter,” by dragging the myths of power down to earth.

Similarly, Yellow Back Radio traps lofty obfuscations in bodies that can be mocked. Polemics against the Catholic Church or Manifest Destiny are all well and good, Reed seems to say—but have you tried a jive-talking pope afraid of witchcraft who flies around in a blimp? And while it’s true that such humor sometimes punches up by punching down, it’s also fairly democratic. For all the humiliation heaped on his antagonists, Loop Garoo is, after all, an unemployed circus performer expelled from heaven and cuckolded by Jesus.

No myth is safe from reevaluation. A motif, like a novel, can be anything it wants to be, and while Reed’s black cowboy may be a whip-toting macho man, his successors in the twenty-first-century “yeehaw agenda” are conspicuously queer and feminist. (As the late Greg Tate wrote in 2008, Reed’s “Age of HooDoo Hieroglyphics” has spawned a “Mojosexual Cotillion.”) Were the “Neo-HooDoo Manifesto” written today, it would have to include the Houston-born Beyoncé Knowles, who donned a Nefertiti crown on tour and flaunted her riding skills in a cowgirl anthem for the video album Lemonade. And if Loop had fathered a Gen-Z bastard, it would certainly be Lil Nas X, who trolled country music’s Drag Gibsons with “Old Town Road” and defied the Bo Shmo homophobes of hip hop at the 2021 BET Awards, where he kissed a male backup dancer onstage in pharaonic raiment. It’s a testament to Reed’s foresight that such artists are still confounding white supremacy and its “working posse of spells.” They won’t be the last cowboys to ride out of Egypt.