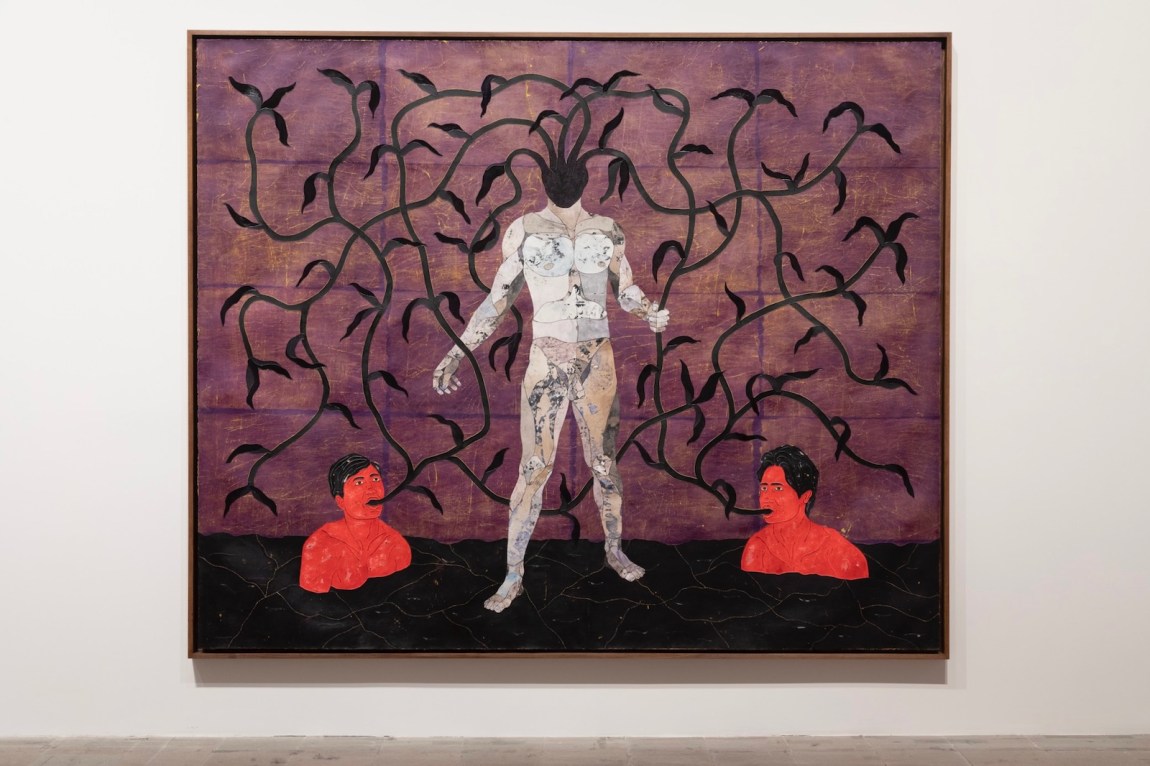

The faceless figure is beautiful, if sinister—ideally proportioned, like Da Vinci’s Vitruvian man. His skin is a mosaic of marbled scrap paper, stained in a spectrum of pinks and grays. Five dark tendrils sprout from his head and branch across the canvas, forming a tangle of thick, tubular foliage over an underlying grid of purple rectangles. He holds one vine like a scepter; at his feet, two half-submerged figures take shoots into their mouths. Are they receiving sustenance? Or, in some peculiar way, sustaining the central figure’s power? Despite its tantalizing pictographic clarity, the image defies explanation.

Prominently featured in this year’s Venice Biennale, Felipe Baeza’s monumental work Por caminos ignorados, por hendiduras secretas, por las misteriosas vetas de troncos recién cortados (2020) exemplifies the uncanny yet alluring forms that have established the thirty-five-year-old artist as one of his generation’s most inventive mythmakers. Its title, borrowed from a poem by the gay Mexican modernist Xavier Villaurrutia, suggests obscure migrations: “By unknown paths, / By secret crevices, / Through the mysterious veins of freshly cut trunks.”

Across his paintings, collages, and prints, Baeza has elaborated the contours of what he’s sometimes called a “queer religion.” His enigmatic figures could be read as saints. Many occupy the picture plane in a state of near-levitation, obeying—if only superficially—the formal logic of Catholic hagiography. And yet his wide-ranging set of visual quotations, from Maya and Babylonian cosmologies to the photography of Graciela Iturbide, demonstrates a fluency that exceeds any one vocabulary, placing icons and divinities from various times and places in direct conversation.

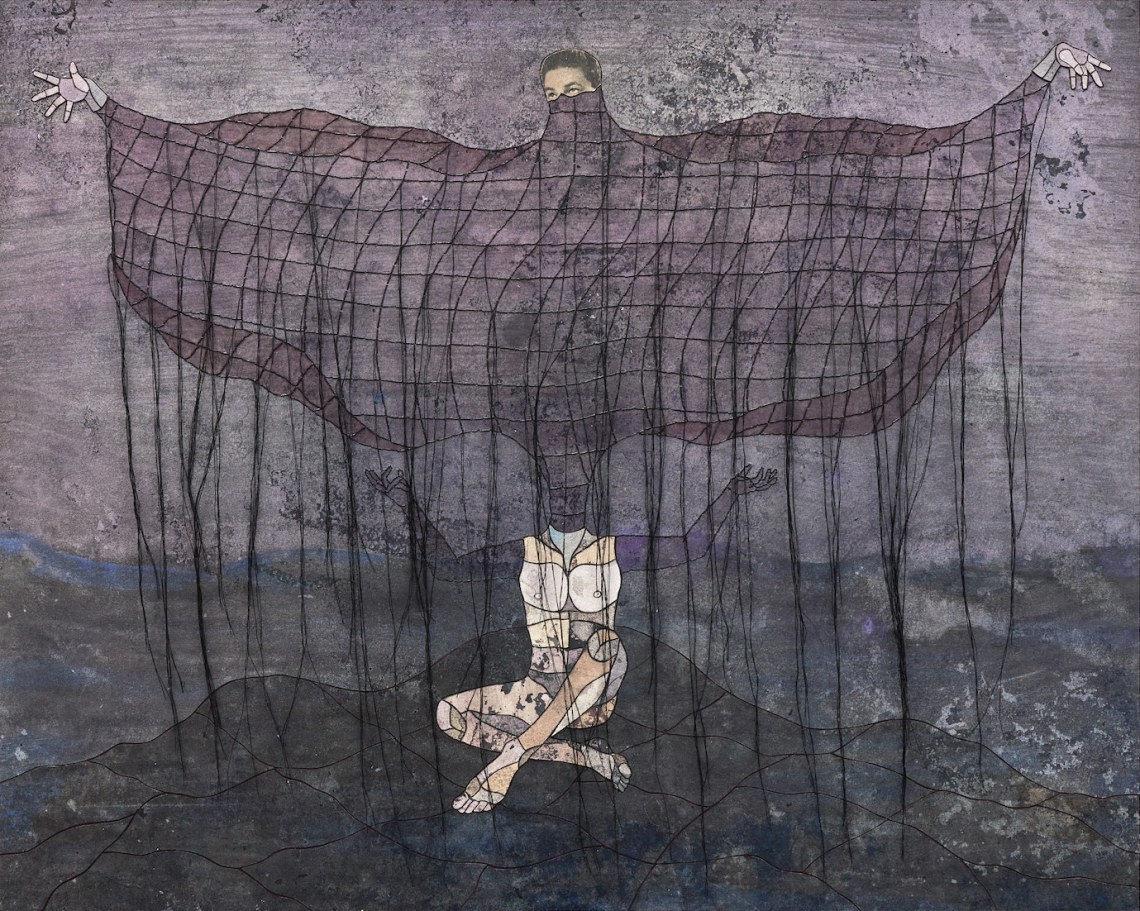

Made Into Being, Baeza’s second solo exhibition at Fortnight Institute in New York, showcases eight smaller works completed this year, from a hieratic wraith made of sinuous flames to a pair of disembodied arms holding up a red-gold sun. The images are fanciful but spare, presented with a captivating boldness that frustrates any attempt to police boundaries between monstrous and divine, human and vegetal, real and unreal. Often they are set in a self-enclosed universe of primordial matter—choppy water, fecund earth—and rendered in a loamy palette of purples, blues, browns, and black, suggesting a new world conjured from rudiment.

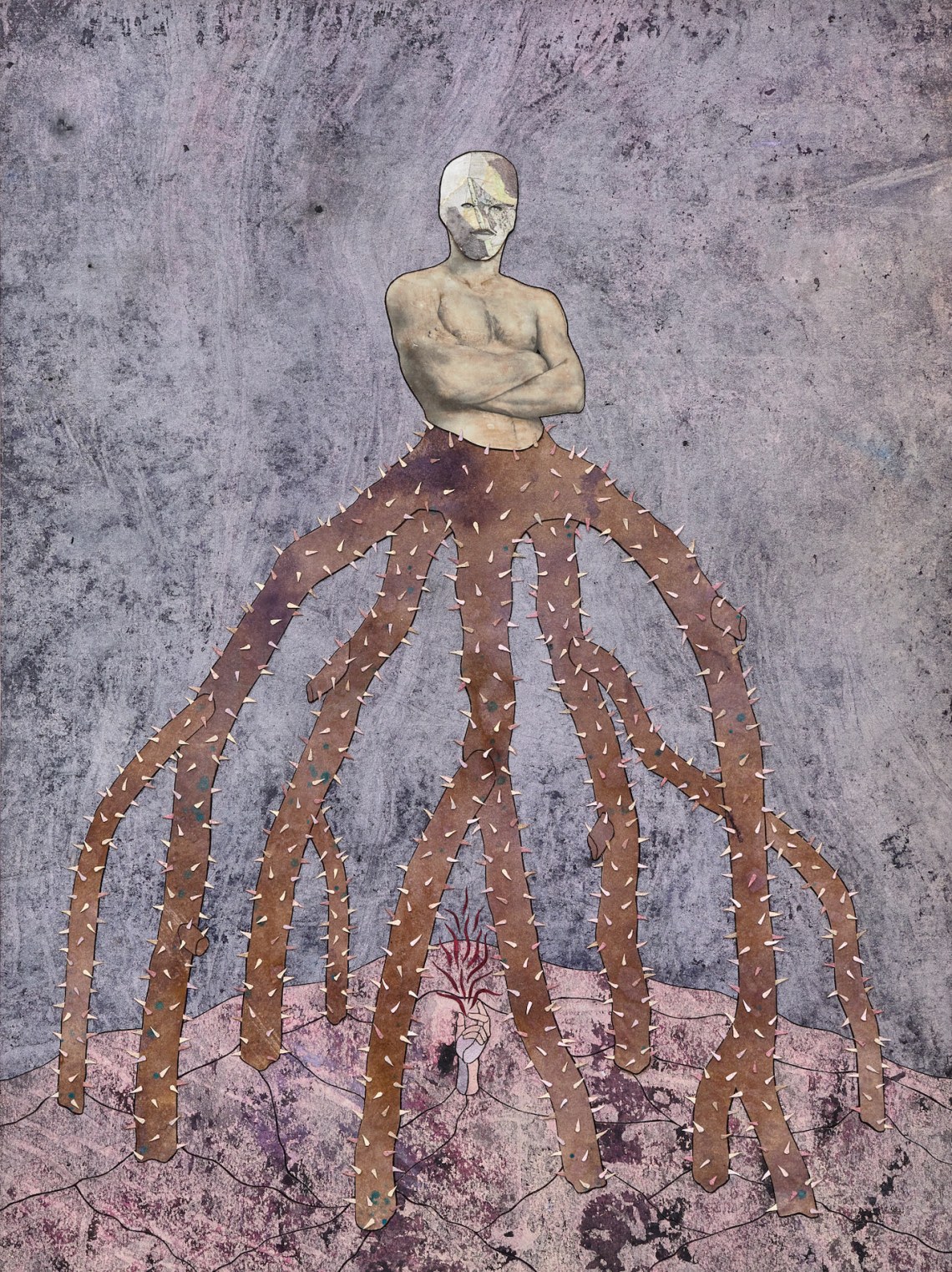

These vignettes recall illustrations from a sacred text. The pounding of steel chopping away at your flesh presents a smooth, armless body in confident contrapposto—at once Virgin of Guadalupe cradled in her mandorla and Botticelli’s Venus rising from the seafoam. In The self must create its own reason for being, a chiseled upper body with crossed arms and recessed eyes grows from a dome of prickly mangrove roots. A pink hand emerges from a patch of scoured earth beneath this imposing entity, bearing a wisp of flame—divine spark, or pilot light? The show’s single sculpture, A self that is not quite here but always in process, is a pair of lead crystal–glass arms cast from the artist’s own and sleeved in thorns, a feature Baeza has likened to the protective layer young ceiba trees develop to warn off predators.

Born in 1987 in Guanajuato, Mexico, and based in Brooklyn, Baeza studied painting and printmaking at the Cooper Union and Yale. Hybrid forms were an early preoccupation; since 2010, he has combined photographs of ancient Mesoamerican artifacts with vintage beefcake erotica. These campy collages, in series titled “Post-Colonial Object of Desire,” “Gente del Occidente de México,” and “Adiós a Calibán,” disclose the logic of dominance and submission that undergirds the supposed objectivity of ethnographic collections, where objects are frequently decontextualized, stripped of meaning and displayed as purely aesthetic wares—a process of simultaneous elevation and devaluation not unlike the one to which “exotic” bodies were subjected at colonial expositions. In the twentieth century, artists like Hannah Höch and Richard Hamilton refashioned images from popular magazines, advertisements, Hollywood films, and auction catalogs to tease out their darker subtexts. Similarly critical, Baeza also revitalizes his source materials: fabulous and creaturely, his chimeras exude a curiously rakish sex appeal.

Baeza’s recent experimentation with collagraphy—a technique that allows for collage-like layering on the printing plate—has given him a subtle but unmistakable command of texture. He manipulates his surfaces with ink, acrylic, graphite, interference powder, egg tempera, varnish, fiber, glitter, and gum arabic until they shimmer and gleam; some of them, viewed from certain angles, have an almost natural iridescence. In his hands, cut-paper fragments are endowed with a solidity and crispness usually associated with marquetry or pietra dura, where particular woods and stones are chosen for their brilliance and grain. (Tavia Nyong’o, in the exhibition essay, compares the effect to stained glass.) Baeza also sometimes incorporates embroidery; several figures limned in twine possess a pleasing dimensionality, as if emerging slowly from the surface. Like the best devotional art, they spark the desire to touch.

Advertisement

Cultural syncretism, Baeza has noted, is always a form of collage. During the colonial era, pre-Columbian artistic traditions fused with Christian imagery across the Americas, resulting in distinctive new styles and genres. Artists of the Cuzco School in Peru, for example, subtly translated Inca iconography into the visual language of European painting; after the Spanish introduced ex-votos to Mexico in the sixteenth century, local populations adapted the medium and claimed it as their own. In the striking compositions on view at the Biennale and at Fortnight, Baeza has continued to articulate a world in the fugitive mode, where fixed notions of identity are sloughed like old skins, where motion and evolution are prioritized over settlement or stability. They share a deep strangeness with some of the most enduring and visionary religious art, like the nearly hallucinogenic images of the fifteenth-century Sienese painter Giovanni di Paolo, whose exuberance and mystery overcome the strictures of reason and allow the miraculous its place in the world. Consider Baeza’s works a codex of divine transformations, each frozen in time like individual frames in a flip book, a prologue to future revelations.