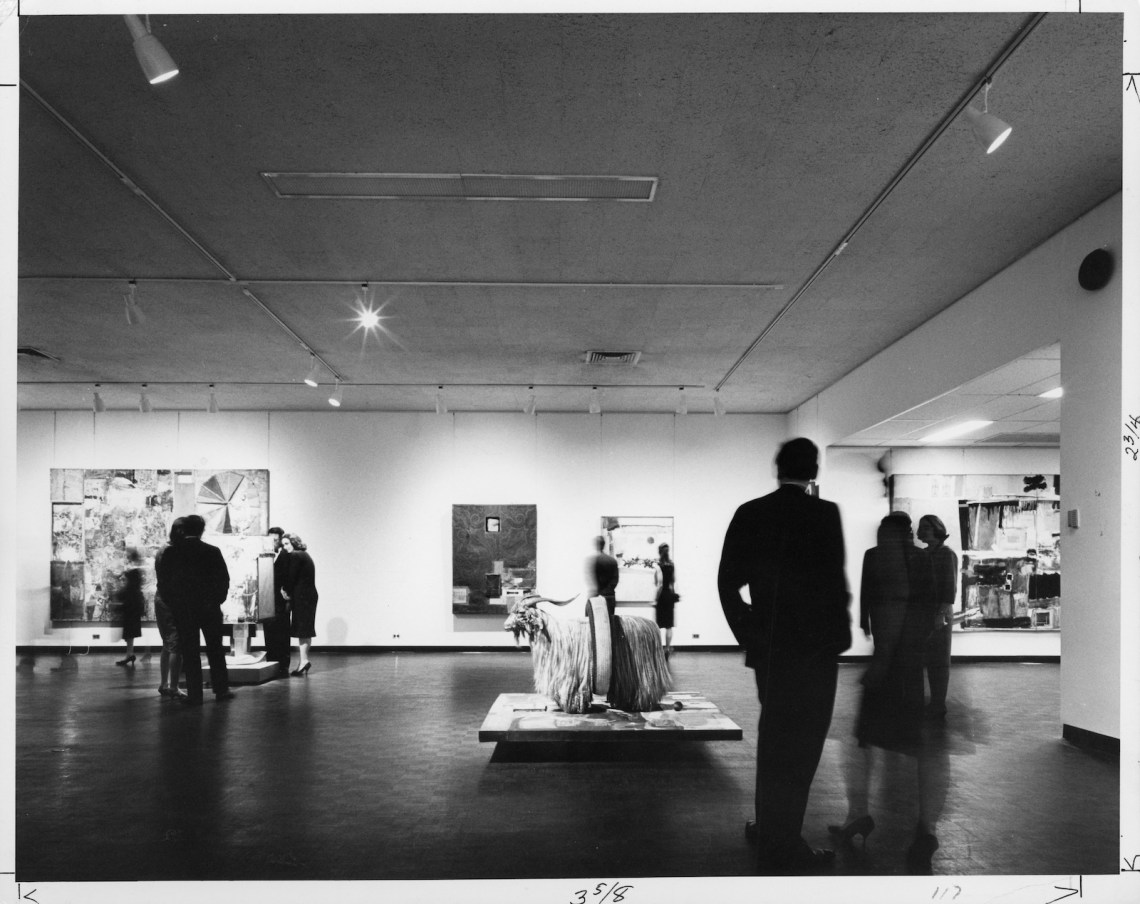

The Jewish Museum’s current show, New York: 1962–1964, is nostalgic not so much for the early Sixties as for a time when, with the art market booming and experimentation in full flower, it seemed that the New York of the Sixties was a sequel to the Paris of the Twenties. Although not as revelatory as the Grey Art Gallery’s 2017 archaeological dig, Inventing Downtown, which brought attention to a number of obscure artists by focusing on the cooperative galleries of the Fifties that incubated the successor movements to Abstract Expressionism, New York: 1962–1964 is a generous show. Conceived by the late Italian curator Germano Celant, it amplifies the triumph of Pop Art, the ascent of Robert Rauschenberg, and the importance of the Jewish Museum curator Alan Solomon. (Rauschenberg had his first New York retrospective at the Jewish Museum in 1963, as did Jasper Johns the following year.) But the period’s most recognizable stars share a busy space with a number of other figures—particularly women and artists of color—and tendencies. The signature work is Marjorie Strider’s meta-Pop pop-out Girl with Radish (1963), an image that revels in, even as it satirizes, visual “pow.”

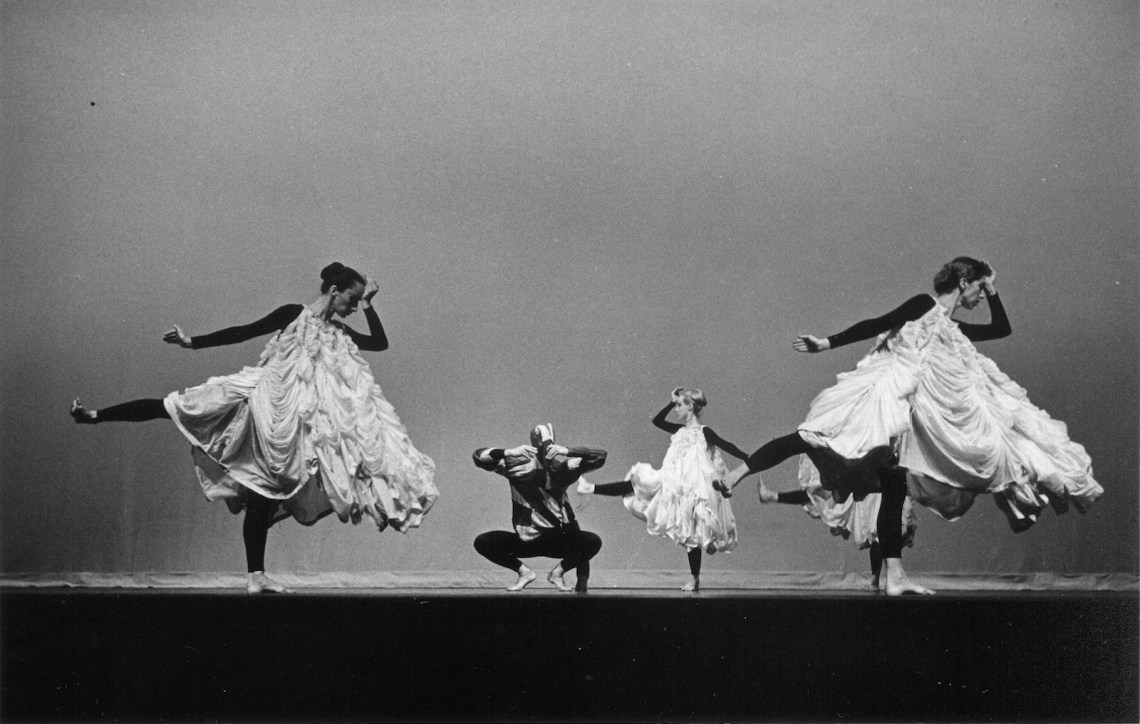

Also present are a sampling of underground movies (many more were shown this summer in a superb parallel show at Lincoln Center organized by Thomas Beard and Dan Sullivan) and various modes of performance, mainly dance. Happenings, a form of avant-garde vaudeville pioneered by painters and pervasive during the period, are difficult to represent. Still, one of the show’s wittiest juxtapositions places a televised recording of a 1963 performance by the New York City Ballet beside “Photographic Ballet,” part of the Fully Guaranteed 12 Fluxus Concerts, a series of actions performed for the camera outside the Fluxhall, at 359 Canal Street. If New York were Paris, there would be a plaque on the building.

Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963), the first and most ironic of underground orgy films, an impoverished parody of Hollywood bacchanalia, is projected in its entirety next to Bob Thompson’s painting The Golden Ass (1963), a more colorful and static (if no less sexualized or playful) study of interlocking forms. An excerpt from Andy Warhol’s eight-hour Empire is tucked into a room consecrated to the minimalist monumental, amid austere untitled boxes by Donald Judd and Robert Morris.

In addition to art, the exhibition includes a model kitchen, a TV room, a reading table with a pile of Mad (and other) magazines, and a jukebox. An alcove devoted to the Kennedy assassination shows a loop of Walter Cronkite’s news bulletin and Warhol’s 1964 Jackie Frieze, serial images of Jacqueline Kennedy’s face in news photos. A larger space is devoted to TV footage and magazine coverage of the speeches at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, although there was also notable agitation for civil rights and racial justice happening during these years in New York City, then Malcolm X’s hometown, much of it directed toward the vernacular Pop Art extravaganza that was the New York World’s Fair.

The Fair, which opened in April 1964, is a fugitive presence in the exhibit (the souvenir calendar in the kitchen is a nice touch), more fully explored by the scholar Susan Murray in her essay for the wonderful catalog. Boosterism on steroids—a celebration of space-age American enterprise, the very consumerism that Pop Art satirized, and New York’s presumed cultural preeminence—it was a natural target for demonstrators who sought to take the stage. In Harlem, the community organizer Jesse Gray organized a block-wide rent strike and convened what he called the World’s Worst Fair, hanging a banner reading “We Don’t Need a World’s Fair—We Need a Fair World” from fire escape to fire escape across East 117th Street.

To protest the Fair’s indifference to existing rules regarding the desegregation of the construction trades, among other injustices, the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) announced an opening-day stall-in: As many as 1,800 drivers were prepared to run out of gas on the network of highways leading to the Fair. In response, Mayor Robert Wagner announced that some thousand police officers in hundreds of vehicles would patrol every road leading into or out of Queens and that police helicopters—one capable of lifting an automobile—would hover overhead. Opening Day brought a cold rain, a third of the 250,000 attendees predicted, and a remarkable absence of traffic. In effect, CORE had created a mental happening—forcing New York’s city fathers to imagine chaotic disorder. Intentional or not, the bluff worked, as did the spectacle of student demonstrators at the Federal Pavilion heckling a sitting American president, Lyndon Johnson.

Advertisement

The Fair commissioned art by Rauschenberg, John Chamberlain, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and, most controversially, Warhol, who proposed creating a mural of a group of portraits: cropped and enlarged mugshots of the New York Police Department’s thirteen most wanted criminals. (It was painted over, most likely at Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s request.) The Fair also precipitated a crackdown on what one Village Voice headline called the city’s “off-beat culture scene.” Lenny Bruce and the exhibitors of Flaming Creatures, Jonas Mekas and Ken Jacobs, were put on trial for obscenity, and café theaters, coffeehouses, strip joints, and gay bars were closed.

*

Nearly three months after the Fair opened, on the afternoon of July 16, a fifteen-year-old Black youth named James Powell was fatally shot by an off-duty, out-of-uniform white police officer in front of the high school where the teenager was taking a remedial reading class in a largely white neighborhood. (The incident was precipitated when an irate white building superintendent turned a water hose on a group of Black students.) That Saturday more than two hundred people gathered for a CORE rally after Powell’s funeral in central Harlem, then marched to the neighborhood police precinct to demand the guilty cop’s arrest. By 10 PM over five hundred people had assembled around Eighth Avenue and 123rd Street. Bottles were thrown and the police fired two thousand rounds of ammunition, some of it at point-blank range. Police violence continued throughout the night. People exiting the subway and other passersby were swept up in the melee. There were several deaths and scores of injuries.

The Harlem uprising took its anthem from one of the summer’s hits, Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street,” included on the jukebox in New York: 1962–1964. Its most famous utterance occurred when a white cop attempted to disperse the crowd by telling everyone to go home, only to be answered, “We are home, baby!”

The city’s racial inequities—and the urban crisis in general—had been illuminated a year earlier by Shirley Clarke’s movie The Cool World, shot on location in Harlem in 1963, which opened at the fashionable Cinema II two days before the Fair. There were good reviews from both The Amsterdam News and The New York Times. (The Times critic Bosley Crowther called it a film of “pounding vitality” that “gives the shattering details of an excellent newspaper exposé.”) Writing in the Village Voice, Andrew Sarris was more uneasy: “By the end of The Cool World, the white race has been reduced to an alien presence from another planet.” Welcome to the Fair.

Bracketed more or less by Rauschenberg’s triumph at the Venice Biennale and the Partisan Review publication of Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp,” The Cool World ran for months. For white New Yorkers it was an eye-opener, a cinematic shot of what CORE activists might call “telling it like it is.” The film, arguably Clarke’s strongest and, because of a conflict with its producer, hardest to see, was among the rarest items in the Lincoln Center program. Its Pop Art-inspired poster appears in the New York 1962–1964 catalogue. The cast is represented by four fat exclamation points with red dots reading “Hooker!” “Fuzz!” “Junk!” “Rumble!”

A week after Harlem erupted, Warhol pulled off his most outrageous stunt: planting a camera by an office window on the forty-first floor of the Time-Life Building and filming eight hours of New York’s ghostly Mount Olympus. “Last Saturday I was present at a historical occasion,” cameraman Jonas Mekas wrote in the Voice. “From 8 PM throughout the night and until dawn the camera was pointed at the Empire State Building, from the 41st floor of the Time-Life Building. The camera never moved once. My guess is that Empire will become the Birth of a Nation of the New Bag Cinema.” There are no people to be seen. At once Pop and minimal, ephemeral and monumental, absurd and heady, dated and timeless, celebratory and derisive, a provocation and an empty gesture, a movie one needn’t see to get and a movie that doesn’t care what you think, Empire is the shadow that 1964 New York cast upon itself.

Advertisement