At a recycling facility outside Kyiv, the face of Vladimir Lenin gazed from the cover of a discarded biography among Russian copies of Dostoevsky, Nabokov, and Pushkin about to be funneled into a shredder. The books, eventually to become egg cartons and toilet paper, came from both private citizens and public libraries across Ukraine. Last June the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture published new guidelines advising libraries and cultural institutions to purge Russian-language books and Russian literature from their collections. It is now illegal to import or distribute books published in Russia. Expanding the national “de-Russification” efforts that began in 2015, the guidelines have received widespread support in parliament and among the public.

Any Ukrainian will tell you that the invasion is not only about territory; it aims to erase Ukrainian identity. The scale of cultural destruction has been staggering. Beyond the widespread looting of Ukrainian artifacts by Russians, the Ministry of Culture has reported that more than 528 of the country’s fifteen thousand public libraries have been damaged or destroyed. Even small institutions, like the museum in the sleepy hamlet of Skovorodynivka dedicated to the eighteenth-century Ukrainian poet and philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda, whose face is on the five-hundred hryvnia bill, have been targeted by rockets.

As a result, calls for categorical de-Russification, controversial before the full-scale invasion, have intensified in tandem with the war. Ukrainian intellectuals from the National Writers’ Union criticized the work of the Kyiv-born Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov as “propaganda literature” and since last August have called for the closure of the Bulgakov Memorial Museum in his childhood home. (The museum is still open for now, three days a week.) Others responded by calling for the dissolution of the National Writers’ Union, itself a creation of the Soviet Union. In Odesa, after months of public debate, a statue of Catherine the Great, considered by some historians the founder of the city, was removed just before the new year. Now a Ukrainian flag stands in its place. Streets across the country have been renamed, Russian music after 1991 is banned from public media, and publishers of Russian-language Ukrainian literature tread lightly.

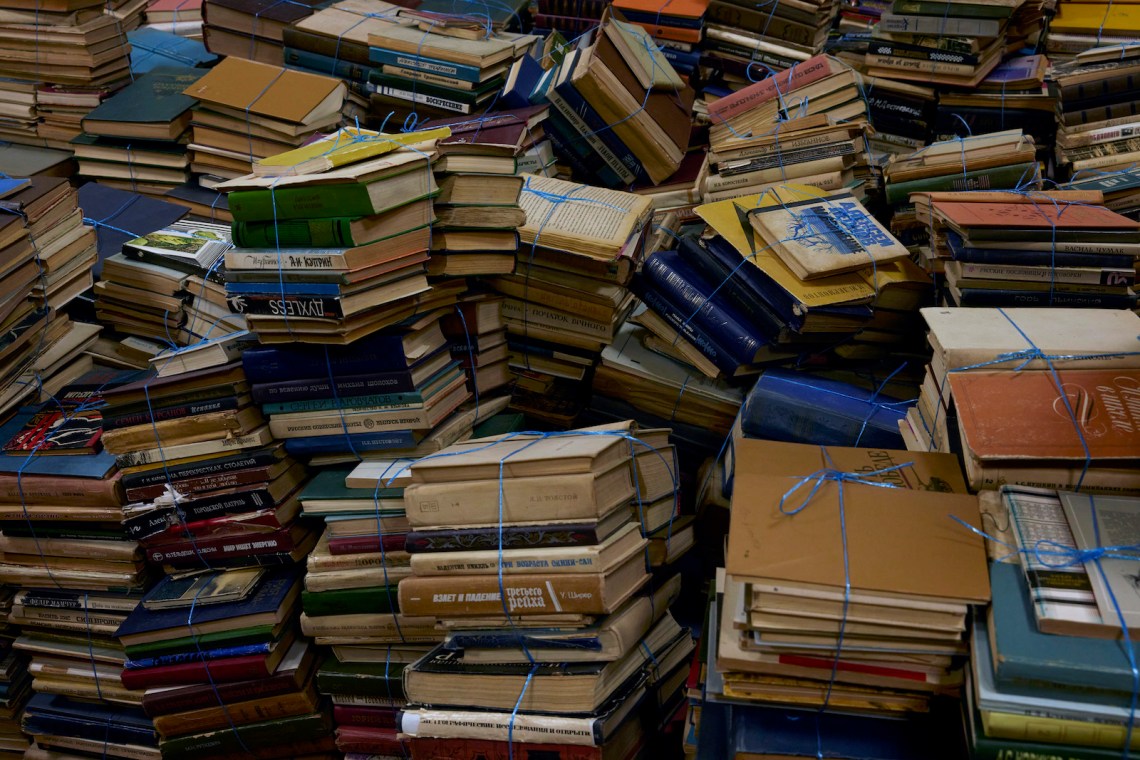

The recycling continues apace. According to Andriy Hrychka, its product manager, as of June 2022 the recycling company Vtorma had been getting eight hundred tons of discarded Russian literature every month since the beginning of the war, 30 percent of all the paper material they received. “We are only destroying that which was forced onto us,” Hrychka said. He grew up in Kyiv speaking Russian and graduated from a Russian-language school, but told me that like “a lot of people” he switched to Ukrainian on February 24, 2022. “A book is a quiet weapon,” he said. “Russia killed our thoughts with their books.”

*

Nearly every town and village in Ukraine has a library. Before 1917 there was one library for every 25,000 Ukrainians. By 1971 there was one per six hundred. Libraries were built across the USSR as part of a vast “illiteracy elimination” program. They were stocked with texts advancing Soviet ideology, such as official party literature and copies of Lenin’s books, and state-sanctioned literature that included Russian classics. They also included Ukrainian language and culture as part of a policy known as korenizatsiya, or indigenization, by which Lenin believed that he could bring nationalists, especially Ukrainian ones, into the Soviet fold. But the policy was inconsistently applied and was considered by some to be contradictory to the project of building an integrated Soviet state. By 1938 Russian was a mandatory subject in all Soviet schools.

The Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky Library in Chernihiv, established in 1948, is a stately yellow building with reading rooms for children, and a mural of sunflowers, Ukraine’s state flower, at the entrance. Chernihiv was shelled for five weeks at the beginning of the invasion and has been accessible only by a pontoon bridge since Russians destroyed the only bridge out of town. Just three days into the invasion, the Kotsiubynsky Library was bombed. Only one of the district’s twenty libraries escaped damage. “Every day of the siege, workers were coming to this library to try and clean up and save the books,” said Anna Pushkar, who became the library’s director when the previous one fled.

A wall that once separated the children’s section was destroyed. Around half the windows have been replaced since they were blown out by missiles, and the others are covered in plywood or plastic. The pipes froze and burst during the winter, leaving the floors flooded and the heat broken. A statue of the library’s namesake, a nineteenth-century impressionist author, was cut cleanly at the shoulders by blowback from a nearby bomb blast. His severed bust has since been placed back on his body. Pushkar and I huddled around an electric radiator. “I am very angry,” she said. She had lived through the siege with her two children for weeks in a cellar. “I do not want, after all we have experienced, that they then go to school and study Russian.”

Advertisement

The Kotsiubynsky Library had 264,000 books in its collection at the start of the war, and 34,000 were deaccessioned in 2022. In January they culled another 10,000. “The process is ongoing,” Pushkar explained. “People return books they checked out before the invasion, and we discard them if they meet the criteria.” She handed me the list of nearly three hundred banned titles and publishers released by the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture. Most were published in Russia after 1991, with titles like New Russia In My Heart, Special Operation Crimea 2014, and Crimea With Russia Forever. But there are a handful of works published in Ukraine or the occupied territories by Ukrainian writers or politicians who had worked under President Viktor Yanukovych, who was ousted during the Maidan protests of 2014. There’s even at least one American: two books about Ukrainian nationalism by John Alexander Armstrong, a former political scientist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, that were reissued by a Russian publisher in 2008 and 2014.

Pushkar explained that Russian authors are banned outright only if they are known to support the war against Ukraine or are published by companies that also produce anti-Ukrainian material. Classics like the works of Pushkin, Lermontov, or Dostoevsky aren’t banned, but there are far fewer on the shelves than there once were. Many Soviet-era collections stocked dozens of copies of Russian titles. Those that have not been deaccessioned due to redundancy and age are mostly shelved in a cramped back room. Pushkar says the library will keep single copies of permitted Russian literature or world literature published in Russian but will remove them as soon as Ukrainian translations become available. That may take a while. The majority of Ukraine’s publishing industry was in the heavily shelled eastern city of Kharkiv.

There is currently no state budget for library acquisitions, and Pushkar and her colleagues have been slowly replenishing their collection with citizen donations. Visitors filed in while we talked, browsing the shelves in the one undamaged room. Along with Ukrainian writers, Stephen King, an outspoken supporter of the Ukrainian cause, is particularly popular. “When Russians invade, they first target libraries, schools, and museums. They imprison Ukrainian language teachers, historians, and activists in basements. They rename the streets and cities. We understand that the Ukrainian identity is very crucial,” Pushkar said. “It is our front line.”

*

Izyum, liberated in September, sits 420 miles east of Chernihiv. Previously a city of 50,000 people, it is now home to only 10,000, mostly pensioners and people who could not afford to leave. Izyum was the site of one of the Russians’ largest civilian massacres; in the forests on the edge of town more than 440 bodies have been exhumed from mass graves.

As we drove through town nearly every building we saw was a charred shell of twisted metal and crumbled concrete. Over a loudspeaker in the central square, the hosts of a Ukrainian radio program discussed plans to liberate Crimea, the Black Sea peninsula illegally annexed by Russia in 2014. There were no air alarms when I visited, but people crossed the square quickly, seeming eager to avoid open spaces. The phone number for the Ukrainian Security Service, which is collecting information on collaborators, was spray-painted on a wall.

The Izyum Central City Library has fared better than most buildings. Out of ten libraries in the district, it’s the only one open. Oksana Zavgorodnya, an elegant older woman wearing a thick purple coat, welcomed us in the main reading room. The shattered windows were covered by plywood, and the room was only partially lit by a few fluorescent lights. Piles of Russian books tied neatly with string lined the wall, ready to be sent for recycling. Empty wooden bookshelves stood propped against another wall in a dark corner. Zavgorodnya said the staff worried every day of the occupation that Russians would come to the library; they had heard from other librarians in the region that Ukrainian patriotic texts were being confiscated, so they hid them. When the Russians arrived in Izyum they mostly destroyed Ukrainian school textbooks, but the winter cold left people desperate enough that they looted the library for books to heat their homes. Most of the precious nineteenth-century holdings have disappeared. “Our job was to save what was left,” the deputy head librarian, Irina Chernyshova, told me.

Advertisement

Because the Izyum library inherited a Soviet collection and is in a predominantly Russian-speaking district, roughly 70 percent of its general collection was in Russian. “Pushkin and Lermontov are on the foreign literature shelves now, but they were not considered foreign writers when I was growing up,” Chernyshova told me. “Being of an older generation, I cannot help but feel it is a pity.” When I asked if she has any favorite Russian literature, she chose The Master and Margarita, but classed Bulgakov as a Ukrainian writer. “A book mustn’t be a political instrument,” she said.

In a village called Babenkove just outside Izyum, the Russians used the cultural center as their headquarters. When they heard the Ukrainian army was advancing, they rushed to clear out. Now the center is almost completely empty. Locals found a machine gun the Russians had left behind. Halloween decorations and children’s drawings line the cinderblock entrance, and dirty mattresses are piled in the hallway. The library—one small, blue room—has just a few bookshelves left. A muddy cave was carved into a small hill just behind the playground around the back of the building. The rest of the village remained mostly unscathed by the occupation.

The temporary head of the center, Anastasiya Garagulya, returned to Babenkove to live with her mother after her apartment in Izyum was shelled. She is thirty years old and previously worked as a cultural journalist and communications director for a nearby museum and cultural center for railway workers. She told me that the previous head, currently being prosecuted for collaboration, not only allowed soldiers to live in the center but also gave them equipment and organized celebrations of Russian holidays, like Victory Day. Garagulya described cultural life under occupation with a laugh. “It was completely surreal. The center would organize events for children and shells were flying overhead.” She speculated that many people only came to the events to receive humanitarian aid.

She heard that the Russian soldiers confiscated books about Maidan. The library’s collection is roughly half Russian, and most people in Babenkove communicate in a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian called Surzhyk. Garagulya says that many of them used to watch a lot of Russian television but are slowly beginning to trust the Ukrainian media. She fully supports the de-Russification campaign. “The only thing that I haven’t quite managed personally is the switch to communicating exclusively in Ukrainian,” she admitted. “I know Ukrainian perfectly, but something prevents me from switching completely.”

*

On February 23, 2022, an open letter in the Russian journal Literaturnaya Gazeta expressed support for the “special military operation” that would follow the next day. It claims Russian writers like Alexander Pushkin and Ukraine’s national poet Taras Shevchenko as “common victories and achievements,” echoing Putin’s rhetoric that Russian and Ukrainian culture are one and the same. The letter then asserts that Russian troops do not “deliberately” kill civilians, and that Ukrainians who “continue to wage a linguistic war on the Russian language, as well as an information war on the Russian collective consciousness,” are only playing victims.

By March five hundred Russian writers had signed. Justifying Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the ongoing war in Ukraine’s east, Putin has claimed to be protecting Russian-speakers in Ukraine. Through speeches, policies, and cultural organizations, he has envisioned a transnational “Russian World” (Russkiy Mir) held together by the Russian language and the reach of Russian literature. Politically, Russia has claimed ownership over the Russian language and by extension the territories where it is spoken.

At the start of the war a number of Ukrainian literary groups, including PEN Ukraine, petitioned for a global boycott of Russian books. The PEN charter states that “in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large, should be left untouched by national or political passion,” and some chapters expressed misgivings; PEN Germany quickly put out a press release stating that “the enemy is Putin, not Pushkin.”

Aleksandr Kabanov, a Ukrainian writer based in Kyiv, is originally from Kherson, a Russian-speaking city at the mouth of the Dnipro River. The city was occupied last year from March to November and is still under near-constant attack from Russians. Kabanov’s mother and brother evacuated when Kherson was liberated and now live with him in Kyiv. He writes in Russian and has won numerous awards for his poetry, including the prestigious Russian Prize. The poems in his 2017 collection In The Enemy’s Tongue address the war in Donbas, the 2014 annexation of Crimea, and the discomforting relationship between language, culture, nationality, and identity between oppressor and oppressed.

In a recent interview Kabanov read a poem from his upcoming book, Snowman’s Son. In the poem, a slime-covered Jesus Christ speaks fluent Russian, surrounded by Ukrainian refugees who have gathered to “listen to the son of God in the tongue of an occupier.”* Christ delivers a devastating message: “there is no more salvation/Time has run out like faith in light and compassion.” Horror “gushes” from the sky “to grab those who did not bow down.” All are killed, saved, and resurrected, and the poem ends in the International Criminal Court of The Hague, which now conducts trials in Surzhyk. Kabanov said of this stanza, “It is not the language that matters, but the context in which it is produced. Especially in international justice.”

He himself is never willing to give up his mother tongue of Ukrainian Russian, a national variant he compares to American as opposed to British English. He maintains that Russia does not have a monopoly over the Russian language. “Language is never to blame for anything,” he told me. “People are always to blame. Specific people.” He also explained that Ukrainian libraries are engaged not in book burning but in a “painful process of cleansing”: “Ukraine is trying to rid itself of everything connected to its semicolonial existence as part of the Russian Empire and the USSR.”

Article 10 of the Ukrainian Constitution, which designates Ukrainian as the state language, also guarantees the “free development, use, and protection” of Russian. Kabanov’s books will still be published in the original Russian, and there are Russian-language publishers that can still operate in Ukraine. But Kabanov, like many of the Ukrainians I spoke with, is unsentimental about Russian culture itself, which he characterized in an interview last May as symbolic of “barbarism, murder and destruction”: “Am I happy about this? No. I empathize with my friends, as well as those Russian cultural figures who love my country and have always supported it. Yes, the abolition of such Russian culture around the world is not entirely fair. But such is the fate of the culture of the enemy.”