A cluster of pipe organ tones rises in the cavernous space of a church. A soprano saxophone holds a long pure note, its overtones joining the organ blur hanging in the air. Then the voices of five women cut through, bright and unconstrained, so in tune with each other, the organ, the saxophone, and the room itself that they seem to shine like rays of light through dusty air. Their near-holler has the insistent timbre and asymmetrical cadence of the Balkans. Instead of church music they sing the clear, declamatory songs of Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian villages—songs about singing, mountains, and girlhood. The voices stop and the organ and saxophone move into the foreground, continuing the cycle of luminous drone and incantatory song until the echoes ebb into silence.

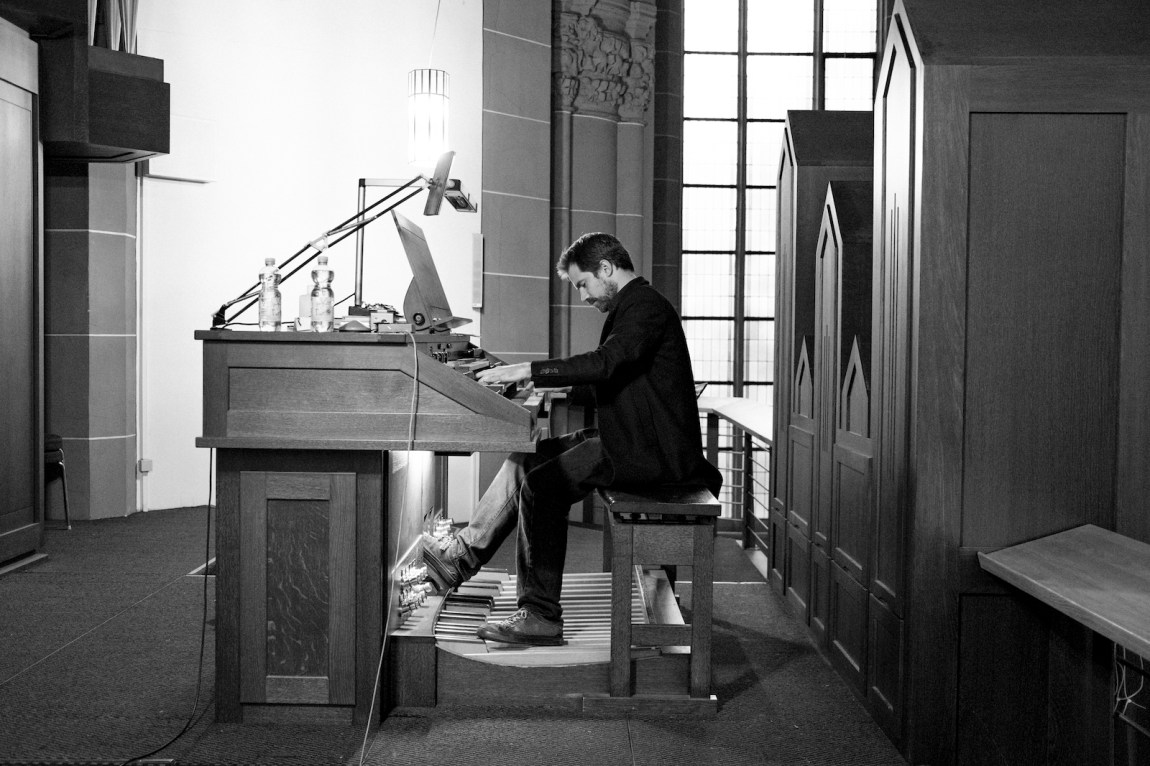

This is the sound of Medna Roso, an exquisite recording of a September 2021 concert in St. Agnes church in Cologne by the English pipe organist and pianist Kit Downes, the New Zealander saxophonist Hayden Chisholm, and PJEV, a women’s vocal ensemble from across the Balkans led by Jovana Lukic. When I first heard the record this May, thanks to a blog post by the eminent English critic Richard Williams, it transported me, as Williams suggested it would, at once to that barely post-lockdown church two years ago and further back in time, to the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Balkan music was almost as inescapable in parts of the US and Europe as Graceland or The Joshua Tree.

Wandering through Tower Records in those years, at the front of the “world music” section it was common to encounter a large display of Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares, a compilation of Bulgarian vocal music released in Switzerland in 1975 but reissued in 1986 by the vibe-heavy British post-punk label 4AD. When that version sold well in Europe, Nonesuch—which in 1967 had started releasing its influential Explorer Series of field recordings from around the world—licensed it in the US. After the Yugoslav Wars broke out in 1991, soundtracks to films like the 1993 Roma music documentary Latcho Drom and the films of Emir Kusturica turned artists like the Romanian Romani virtuosi Taraf de Haïdouks and Boban Marković’s Serbian brass brand into staples of world music festivals. There was enough money flowing through the then-booming industry for major labels like Nonesuch, at that time still a subsidiary of Elektra Records, to take chances on Bulgarian choirs. Globally minded music lovers rewarded them. Nonesuch sold 500,000 copies of Le Mystère.

To a generation of musicians emerging as the Berlin Wall fell, records like Le Mystère and Orpheus Ascending by Ivo Papasov and His Bulgarian Wedding Band became foundational influences. Their fast, odd grooves and non-diatonic modes gave jazz musicians in particular a way to apply their advanced chops without the smarmy swagger of fusion or the blues-based languages promoted by neotraditionalists like Stanley Crouch and Wynton Marsalis. In the world of downtown New York jazz, facility with the rhythms of the Balkans was as important a technical benchmark for an emerging professional musician as learning standard tunes, Charlie Parker’s twisting bebop lines, or the lightning-fast cubist harmony of John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps.” Mashups of those technical tropes, like a standard played in a Balkan-like groove, are still common enough to be a jazz school cliché. Explicitly Balkan-inspired bands from New York—among them Pachora and Dave Douglas’s Tiny Bell Trio, both featuring the powerhouse drummer Jim Black and the guitarist Brad Shepik—turned this phenomenon into a subgenre.

Jazz musicians adopted a new set of rhythmic and harmonic tools from Balkan music, but without canonizing a particular composer—like Antônio Carlos Jobim during the 1960s Bossa Nova craze—or even a particular set of songs from a specific place like Bulgaria or Serbia. Instead, for many jazz players Balkanness became a shorthand for a set of time signatures and scales, with little sense of where they came from or the people who played them. There were collaborations between New York musicians and players from the Balkans (I participated in a few of them), and jazz musicians did dedicate themselves to learning traditional Balkan styles, sometimes becoming part of the robust folk dance community that has thrived in the US for decades. But much of the time Balkan music was just another platform for the jazz players to do what they do best—improvise. In a 2004 collaboration at the North Sea Jazz Festival in the Hague, the master saxophonist Michael Brecker and the outstanding Norwegian band Farmer’s Market used a Bulgarian piece as part of a virtuoso display that incorporates ragtime, throat singing, approximately Indian vocalization, and R&B. While technically thrilling, it’s unclear what any of these shifts in genre have to do with each other besides trickiness.

Advertisement

*

The encounter between improvising musicians and traditional Balkan music documented on Medna Roso recalls these ideas from twenty-five years ago but also shows us a way past them. Downes and Chisholm are not playing jazz or practicing ethnomusicology, and while their virtuosity is evident, nor are they showing off their chops. They are improvising in the contemporary style that relies on drones and bold, gestural playing, generally without reference to specific pieces or genres. They meet on equal ground with the singers, whose songs maintain their integrity even as they threaten to blur into the improvisations. The instrumental sections—with their monumental clamor, hushed chordal clouds, chest-rattling sub-bass, post-minimalist riffs, and electronic colors—almost never echo the melodies, harmonies, or rhythms of the songs, never attempt to sound like Balkan music. Instead they join in a shared sense of precise microtonal tuning, deploying oblique drones and patterns that highlight PJEV’s crystalline intervals.

Downes’s organ and Chisholm’s woodwinds surround the singers on all sides, occupying registers far below and above theirs as well as occurring before and after them in time. Rather than assimilate into the haze of drone and reverb, the vocalists charge it with the clarity of their intonation and the exactitude of their timing. “Even to this day I am not sure what happened there in Cologne,” Lukic says in the record’s press release. “It felt from the very first moment that we’d suddenly received big wide stork wings. Their strong and deep music gave us so much support and powerful wind in our backs, so we just had to carefully surf on it.”

The album begins with a soft drifting tone—it’s unclear if it’s organ or electronics—that grows into a monumental blast of pipe organ swirl. After a short flutter of saxophone, PJEV enters with “Listaj goro ne žali be’ara,” a song from Western Serbia about a young girl poised between youth in nature and a possible future as a military wife. “Bloom you mountain,” it begins, “don’t regret the blooming flowers.” It ends, “The yellow forest rustles, I have a sweetheart at school/At school by the window, studying to become a commandant.” Downes and Chisholm hover behind the song, floating in and out, their notes resonating in the church’s slowly decaying echo.

The pattern continues. Short instrumental improvisations alternate with songs, obliquely reflecting each other but never the same thing—less like the standard relationship between singer and accompanist than like the parallel, equal, but not mimetic relationship between John Cage’s music and Merce Cunningham’s dance. At the set’s halfway point, we finally hear a fragment of melody from Chisholm that leads to the album’s most intense organ storm, a giant chromatic run followed by a nearly silent drone. That fragment foreshadows the album’s title track, “Medna roso, gdje si zimovala,” from Croatia:

Honey dew, where did you spend the winter?

With the girl, under her white neck

Where the necklace with small pearls sits

Oh, the meadow, young every year,

And me now, and never again.

As PJEV sing, the organ drone slowly grows, adding harmonic complexity until it abruptly ends and something like a train whistle takes over. We drift deeper into the space of the church, its air blowing through the organ and Chisholm’s breath through the saxophone, leading us to another song. On this recording the idea of people with different ways of making music coming together to create something transcendent feels powerfully alive.