Near the start of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s most recent novel, Afterlives, two men in a coastal town in German East Africa in the early 1900s muse on the possibility of a European war landing upon their shores:

They were preoccupied at the time with rumors of the coming conflict with the British, which people were saying was going to be a big war, not like the small ones before against the Arabs and the Waswahili and the Wahehe and the Wanyamwezi and the Wameru and all the others. Those were terrible enough but this is going to be a big war! They have gunships the size of a hill and ships that can travel underwater and guns that can bombard a town miles away. There is even talk of a machine that can fly although no one has seen one.

The German occupation of East Africa began in 1884, led by the commercial agent Carl Peters, founder of the German East Africa Company, who—in keeping with the methods of the time—acquired trading rights through controversial deals with local rulers as far as the Rufiji River, about a hundred miles south of Dar es Salaam in present-day Tanzania, and stretching north to Witu, on the coast near Lamu, in present-day Kenya. These sham treaties were recognized at the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, where the major powers of Europe partitioned Africa in order to avoid conflict over how its spoils should be divided, with no regard for the wishes of the African populations.

The Zanzibar Archipelago, where Gurnah grew up, lies in the Indian Ocean off the East African coast. It was for centuries a flourishing trading center dealing principally in spices and slaves; trading caravans traveled from the islands into the continent’s interior. Zanzibar formed part of the empire of the sultan of Oman, but in 1862 Britain turned it into a client state by backing the sultan of Zanzibar’s independence from Muscat. Following the Berlin Conference, and by agreement between Germany and Britain, Zanzibar’s control of mainland trade was limited to a ten-mile strip along the coast, part of which Germany leased from the sultan for commercial exploitation. Though Afterlives does not name its coastal town, it is clear that it is in this area.

Soon after the Berlin Conference, various factions of the coastal and interior peoples, including even the usually conservative Swahili merchants, rejected German attempts at governance through a series of uprisings that were brutally suppressed by the German Imperial Army with the assistance of the British Navy, which blockaded the coast to impede the import of supplies and arms. In 1890 Zanzibar became a British protectorate, while Germany attempted to maintain control of its colony on the mainland. But in 1905 the Maji Maji Rebellion began—a two-year protest against forced cotton production and scandalous German abuses, including flogging, summary executions, the murder of women and children, and even castration—the suppression of which required reinforcements sent from Germany. The rebellion remains the largest uprising in German colonial history, claiming around 100,000 lives.

The so-called Scramble for Africa has been well documented. Thomas Pakenham’s seven-hundred-page The Scramble for Africa (1991) focused on the stories of those often mythologized European men, such as Peters, who laid claim to the continent’s riches, and those whose political ambitions shaped its future: King Leopold II of Belgium and German chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who convened the Berlin Conference, along with their British and French contemporaries up to and including Winston Churchill. Through them Pakenham traced the iterations of the European encounter with Africa from the fringes of the continent, trading slaves out of forts on the West Coast, to the expeditions into the interior, to the wholesale colonial endeavor—as well as the arrival of missionaries, among them David Livingstone, who coined the term the “three C’s” to describe the colonial enterprise: Christianity, Commerce, Civilization.

The African view of European activity was less favorable. Jomo Kenyatta, an anthropologist and activist who was instrumental in leading the fight against British rule in Kenya—and who went on to become the newly independent nation’s first president in 1964—wrote in the final pages of his 1938 book Facing Mount Kenya:

When he [the European] explains, to his own satisfaction and after the most superficial glance at the issues involved, that he is doing this for the sake of the Africans, to “civilize” them, “teach them the disciplinary value of regular work,” and “give them the benefit of European progressive ideas,” he is adding insult to injury, and need expect to convince no one but himself….

The Europeans…speak as if it was somehow beneficial to an African to work for them instead of for himself, and to make sure that he will receive this benefit they do their best to take away his land and leave him with no alternative. Along with his land they rob him of his government, condemn his religious ideas, and ignore his fundamental conceptions of justice and morals, all in the name of civilisation and progress.

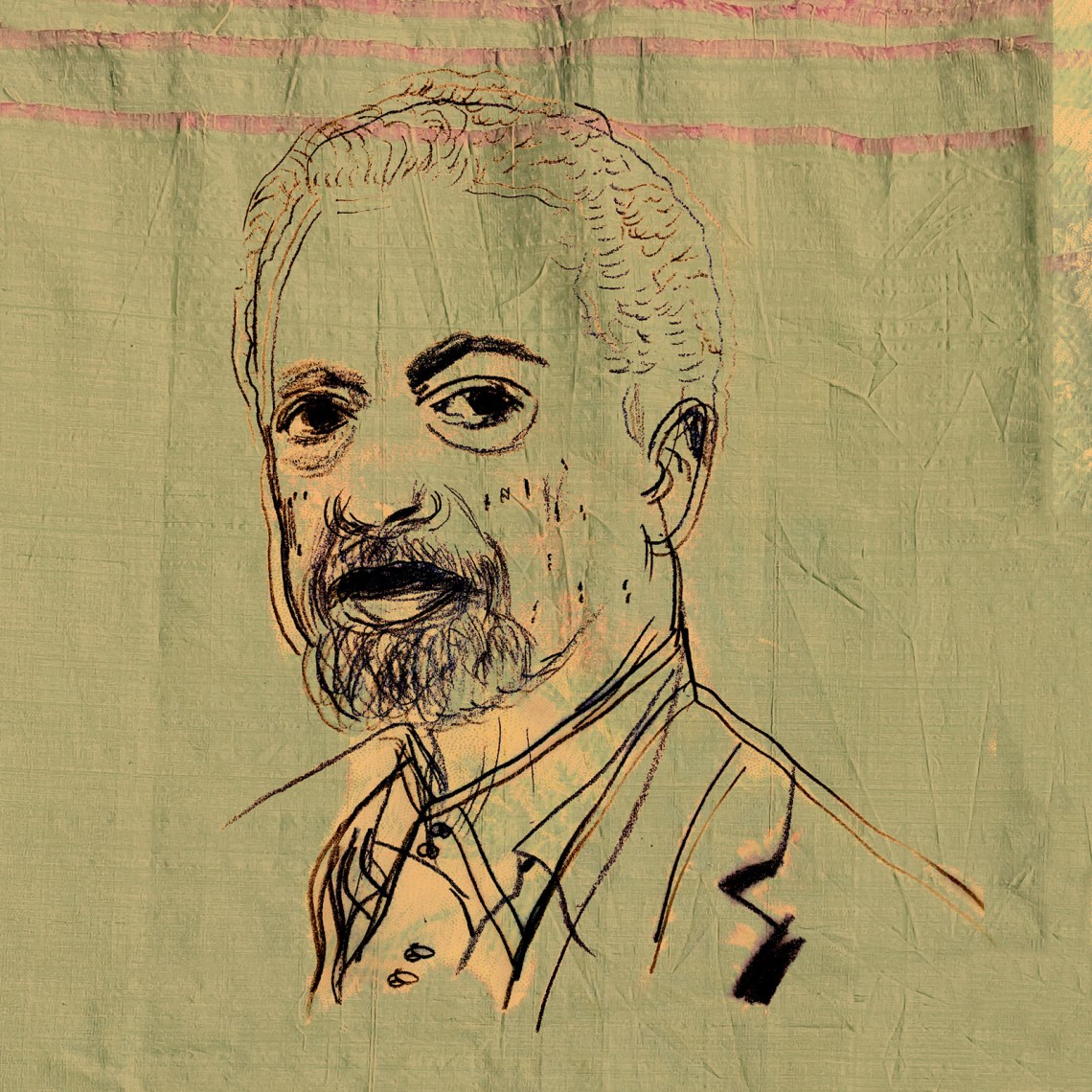

This is the literary landscape of Abdulrazak Gurnah, whose ten novels—including Afterlives, the first of his books to be published in the United States since he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2021—narrate the histories and experiences of the people whose lives were upended in the decades of tumult created by East Africa’s collision with Europe. Specifically, he chronicles the lives of ordinary people: those who may be poor, or young, or female, or somehow dispossessed, and therefore not in control of their own fates. For control rests in the hands of more powerful individuals and governments, near and far.

Advertisement

Gurnah was born in colonial Zanzibar in 1948 and grew up in Zanzibar City, in an area then known as Malindi (now Funguni). The family home was close to the docks; an upstairs window afforded a view of the harbor and of arriving ships with their multitudes of passengers from all over East Africa and the islands. In a 2015 essay, “Learning to Read,” Gurnah describes the swirl of languages around him:

My encounter with Kiswahili was as a native speaker, born into it in our house in Malindi. Many people in Malindi spoke a smattering of Arabic as well, and some spoke it fluently. My father was a fluent speaker; my mother could not speak a word. From other houses you could hear the sound of Kutchi or Somali, or the inflexions of Kingazidja.1

Gurnah attended Quranic school and primary school, as well as King George VI Secondary School (later renamed for Patrice Lumumba, the murdered Congolese leader and patriot), where the students followed the Cambridge curriculum and sat the same exams as their British peers. However, Zanzibar’s independence in 1963 and the overthrow of the sultan in January 1964, along with unification with Tanganyika to form the new country of Tanzania, brought turmoil during which thousands of Zanzibari Arabs were slaughtered by the majority black African population. By the time Gurnah completed secondary school in 1966, advanced schooling in Zanzibar had been shut down.

At eighteen, Gurnah went to England with the hope of continuing his education. He studied engineering in Canterbury and then worked for three years as a hospital orderly, after which he earned a teaching degree at Christ Church College. He then taught high school in the seaside town of Dover in the late 1970s—a time of heightened racial tensions. In the early 1980s, while working toward his doctorate in West African literature at the University of Kent, he taught at Bayero University Kano in northern Nigeria, and after his return to the UK, in 1985, he accepted a position teaching postcolonial literature at the University of Kent, where he is now an emeritus professor.

Gurnah achieved his dreams of academic excellence, but the terror of flight and the bitterness of exile left their mark. He began to write about “where I had left or indeed why I had left,” as well as about arriving in a new, sometimes hostile place, laden with memories of the past. Often in his novels a young man manages to escape abroad to study. Hassan, the fifteen-year-old boy at the center of his first book, Memory of Departure (1987), breaks from a family cycle of despair—an alcoholic father, a sister forced into prostituting herself, a brother who burns to death in an accident following a beating by his father, a mother resigned to her own unhappiness—when he leaves his home in an unnamed African country to attend school and live with wealthy relatives in Nairobi. An innocent in the city, he is soon taken advantage of by a young man who pretends to befriend him and is thrown out of his uncle’s house before leaving to pursue his academic dreams in Europe by working for his passage on a boat. Many of Gurnah’s other novels, including By the Sea (2001) and Desertion (2005),2 similarly feature characters who, with greater or lesser degrees of success, make their lives away from their homeland, in the country of their colonizer.

The dank reality of post-Empire England is equally a preoccupation of much of Gurnah’s work. His second novel, Pilgrims Way (1988), describes with biting humor the experiences of a young Tanzanian man, Daud, who works as a hospital porter in a small English town and lacks the financial wherewithal either to complete his studies or to return home. Far from being civilized, the English are dismissive and cruel, as well as slovenly and mediocre, possessed of an arrogance based solely on an assumed superiority to the dark-skinned. When Daud is invited to the home of a young English acquaintance, he is subjected by his friend’s father to a series of indignities and impertinences:

Advertisement

“I have nothing against you personally,” Mr. Marsh said, turning to Daud. “After all we invited you to our house. But there are just too many of you people here now, and we don’t want the chaos of all those places to be brought to us here. We’ve done enough for your people already.”

“You should’ve thought of all this before,” Daud said. “Before you set off on your civilising mission.”

Daud contemplates Mr. Marsh as an exemplar of England’s postcolonial decline:

To be as blissfully unaware of his ridiculousness as this man was a quality only builders of empires possessed. It was the same with those Chinese and Roman Kings who had disregarded the most obvious hints of their impending destruction. They had pranced and preened, and could not believe what pathetically vulnerable figures they cut in front of their barbarian enemies. They were so convinced of their superiority that they could not take the danger seriously.

Thus Gurnah reverses the literary gaze, viewing the colonizer from the perspective of the colonized. As in Conrad, the true heart of darkness is not Africa but Europe.

Most of Gurnah’s novels are concerned with the epilogue of empire, the alienation the formerly colonized experience in the lands that have forced upon them so much of their language, culture, and politics. Only two are set during the prelude to the European empire and exclusively in East Africa: Paradise—which was short-listed for the Booker Prize in 1994 and is perhaps his best-known novel—and Afterlives.

Paradise takes place during the era of Carl Peters, the German commercial agent. A third of the way into the book, a pair of minor characters makes the historical situation clear. Hussein, a shopkeeper in the mountain town of Olmorog who is originally from Zanzibar, prophesizes to his friend Kalasinga, a Sikh mechanic:

Everything is in turmoil. These Europeans are very determined, and as they fight over the prosperity of the earth they will crush all of us. You’d be a fool to think they’re here to do anything that is good. It isn’t trade they’re after, but the land itself. And everything in it…us.

Kalasinga objects, telling him that the Europeans have ruled India for centuries and in South Africa have killed in pursuit of gold and diamonds, but that this part of the continent has no such riches: “What is there here? They’ll argue and squabble, steal this and that, maybe fight one petty war after another, and when they become tired they’ll go home.” Hussein, though, describes what has already been done, how the highlands, the best land, has already been seized, the leaders killed, and the people turned into servants of the whites:

We’ll lose everything, including the way we live…. And these young people will lose even more. One day they’ll make them spit on all that we know, and will make them recite their laws and their story of the world as if it were the holy word.

In the book’s opening pages, a woman in the small town of Kawa—once “a boom town when the Germans had used it as a depot for the railway line they were building to the highlands of the interior”—prepares a feast for an honored guest, a wealthy merchant from the coast named Uncle Aziz, whose exact relationship to her family is unclear. Is he a distant relative, a family friend? As the woman works, her twelve-year-old son, Yusuf, darts in and out of the kitchen. After the meal, when Uncle Aziz departs, Yusuf is sent with him—given, it transpires, in lieu of debts unpaid by his father.

The boy travels by the merchant’s side from the coast into the interior with a caravan of goods that Uncle Aziz hopes to exchange in a deal with a local sultan. The journey involves setback after setback, as well as several moments of horror (a village in the aftermath of a raid by a neighboring tribe, a woman eaten by a crocodile, a porter attacked by a hyena), and finally ends in disaster. When Uncle Aziz declines to drink the sultan’s beer, the sultan mocks him and his Muslim faith and soon takes the party captive, seizing their goods—in retribution, he says, for the slaving past of Arabs like Uncle Aziz.

Shortly afterward a European man, guarded by askari—locally recruited African soldiers—arrives and orders the return of the goods. Uncle Aziz realizes that the sultan’s newfound bravado has its roots in the arrival of these new European trading partners and the wealth and protection they promise. Though the merchant has gotten his goods back, he is humiliated, knowing that this was achieved only on the orders of the European. All power belongs to the white man. A new era has arrived.

Back at the merchant’s shop on the coast, a former henchman to Uncle Aziz tells Yusuf bitterly: “There will be no more journeys now the European dogs are everywhere.” Hearing this, and having seen the evident authority of the European who intervened in the merchant’s conflict with the sultan, Yusuf realizes the precarity of his own future with the merchant. When another contingent of askari and their German officer pass through the town, he runs away to join them.

Afterlives picks up where Paradise left off. The novel begins with Khalifa, the son of an African woman and an Indian bookkeeper who works for a Gujarati landowner on his estate in coastal East Africa. As a young man, Khalifa follows in his father’s footsteps, first becoming bookkeeper to a pair of Gujarati moneylenders and later taking a job as clerk to a merchant named Amur Biashara.

By this time, in the early 1900s, the Germans control the coastal territories, suppressing native insurrections with the use of a locally raised army, the Schutztruppe. The town where Khalifa lives, however, remains peaceful. In 1907 he marries Bi Asha, a niece of Amur Biashara. The couple struggle to have children and, after three miscarriages in as many years, give up hope of ever having a child of their own. Around this time Khalifa meets and befriends an itinerant young man named Ilyas, who has come to town to work at a German-run sisal estate, and it is this relationship that marks the start of the rest of the novel’s chain of events.

As a child Ilyas ran away from home and was kidnapped by an askari Schutztruppe soldier, from whom he was then rescued by a German officer who sent him to a mission school. Ten years have passed since Ilyas last saw his family. At Khalifa’s urging, Ilyas makes a trip to his home village, where he discovers that his parents are dead and his young orphaned sister, Afiya—of whose existence he was unaware—is being mistreated by the family that took her in. Ilyas brings her to live with him in the town. However, when the war begins in 1914, he volunteers for the Schutztruppe, abandoning his sister and returning her to the care of the abusive family, from whom, months later, she is rescued by Khalifa.

In Ilyas, Gurnah has created a character who exemplifies a colonial mentality, with an admiration of Germans rooted in his time at the mission school. “They had to be harsh,” Ilyas insists in a discussion about the German response to the rebellions, “because that’s the only way savage people can be made to understand order and obedience”—to which one listener replies, “My friend, they have eaten you.” In fact Ilyas has been so completely alienated from his own culture that, in one scene, he is revealed to have forgotten the rituals of prayer at the mosque. But there is likely more to his decision to sign up to fight for the Germans. Askari were typically drawn from the impoverished classes: young men for whom military life offered an opportunity for advancement. Askari occupied a position that blurred the lines between the colonizer and the colonized. They helped build, maintain, and defend the colonial state and in the process acquired a certain respectability, both revered and feared.

This is the last we hear of Ilyas for most of the book. In a sudden shift, Gurnah introduces the reader to Hamza, another young man newly recruited into the askari. Through Hamza’s eyes we see details of the war and the place the askari occupy, including even the washing arrangements: the askari wash downstream of the German officers but upstream of the African porters, whom everyone treats with undisguised contempt.

The growing losses of the Germans and their Schutztruppe are indicated less by descriptions of the violence itself than by the decline in morale among the officers and the men following the 1917 Battle of Mahiwa, in which the British used contingents of Nigerian troops: Africans fighting Africans on behalf of the colonizers. Though the Germans were initially victorious, their supplies were too depleted for them to take advantage of this, eventually resulting in the German withdrawal from East Africa.

From the start, Hamza is ill-suited to askari life. He is saved from fighting by the attentions of the German commander, who chooses him to be his personal batman (orderly). This position, however, earns Hamza scorn from the askari and Germans alike: “Sometimes when Hamza was serving in the mess and he was close to the medical officer’s chair, he felt his thigh being stroked as he passed.” To another German officer, the Feldwebel, he becomes an object of special loathing:

He called Hamza a toy soldier behind the commanding officer’s back.

“Whose toy are you? You are his pretty toy, little shoga plaything, aren’t you?” he said, wagging a finger in disdainful warning and once reaching out and squeezing Hamza’s nipple. “You make me sick.”

Meanwhile the commander teaches Hamza German and to read Schiller, but is equally capable of making him the object of his frustrations:

“I pulled you out of that line because I liked the look of you,” the officer said, standing two paces in front of him. “Are you frightened of me? I like people to be frightened of me. It makes me strong.”

The officer stepped forward and slapped Hamza on the left cheek then slapped him with the back of his hand on the right cheek.

In Paradise Gurnah explored tensions between the Arab-descended people of the East African coast and Zanzibar and the black Africans of the interior. Yet in Afterlives, the fact that Khalifa’s father was an Indian married to an African woman is described only to explain how Khalifa came to acquire an education and a job as a bookkeeper—through the influence of his family’s Indian connections. Beyond that, Gurnah makes little mention of race. The focus of Afterlives is firmly on the fate of a population at the mercy of colonial ambitions.

As the German officers succumb to drink and sickness over the course of the war, the askari become mutinous. But it is the desertion of the unit one night by the lowly porters that proves the Germans’ final undoing. With morale at an all-time low, the drunken Feldwebel attacks Hamza with a sword, convinced that he must have known what the porters were planning. At the behest of the commander, Hamza is taken to a nearby German mission to recover from his wounds.

Thus far, the novel has toggled between chapters about Hamza and chapters about Khalifa, his wife, Asha, and Afiya, whom they care for—though the girl occupies a role closer to servant than daughter and, as she enters puberty, suffers under Asha’s accusing eye. But with the end of the war, Hamza arrives in the coastal town where they live. Gurnah alerts the reader, as if in passing, that this is a place Hamza already knows:

Hamza remembered that from the time before, how the road ran past the house where he lived, and how then it narrowed down to the tight aperture that opened out into the interior.

Gurnah is letting the reader into the secret of Hamza’s identity—for Hamza is, as Gurnah has confirmed in interviews, none other than Yusuf, the boy we last saw running away to join the askari in the closing pages of Paradise.

Seeking work, Hamza is given a job by Khalifa’s employer. Soon Khalifa befriends and helps him, much as he did Ilyas—who has so far failed to return from the war and from whom nothing has been heard. When Afiya, now a young woman, meets Hamza, they fall in love. It is a love underpinned by loss, a fear of abandonment, and the desire to create some part of their lives beyond the control of other people. The remainder of Afterlives is their story, and the story of the son Afiya bears and names Ilyas—after the boy’s long-lost uncle.

The creation of the self through improvisation out of necessity is a recurring theme in Gurnah’s novels. His characters leave home, face the world alone, and reinvent themselves. For many of them, independence comes through education. This is true for Hamza, who has learned to speak, read, and write German and is eventually able to rise above his humble station. Afiya also knows how to read and write, having been taught by her brother and encouraged by Khalifa. She and Hamza pass these skills on to their son.

Not all of Gurnah’s characters are able to improvise so effectively. Some, like Afiya’s brother, become lost. Hamza determines to find Ilyas by writing to the German missionaries who tended him during his convalescence, but his efforts yield nothing conclusive. Many years later the younger Ilyas is awarded a scholarship to West Germany, and it is he who finally uncovers the fate of his missing uncle.

It turns out that the elder Ilyas, cut off from his family and his Muslim faith, attempted to reinvent himself in Germany after the war, forever ruing the passing of the empire. He performed in Hamburg nightclubs wearing his askari uniform and attended Nazi rallies in the rising Reich. His humiliating fate is told in only a few pages at the book’s close. It is an outcome so shocking that one wishes Gurnah had given it more space. Yet perhaps doing so would have detracted from the humbler—and in its own way richer and more optimistic—story of Hamza and Afiya, who do, in the end, gain the autonomy they so desire over their own lives.

Thus the ending of Afterlives, symphonic in its scope, comes not with the clash of cymbals but with the quiet close of a gentler movement. Gurnah’s novels never cease to demonstrate how the minutiae of lives are affected by political events far beyond their power. Though his characters attempt to wrest control when they have the opportunity to do so, history and the winds of global change direct the course of their lives far more than their individual wills ever can.

This Issue

December 7, 2023

No Endgame in Gaza

Invasion, Day by Day

Gut Instincts

-

1

Included in Abdulrazak Gurnah, Map Reading: The Nobel Lecture and Other Writings (Bloomsbury, 2022). ↩

-

2

These two novels have just been reissued in the US by Riverhead. Desertion includes an afterword adapted from the address Gurnah gave to the Swedish Academy upon receiving the Nobel Prize in 2021; By the Sea includes an afterword adapted from a talk I gave about his work at the 2022 PEN World Voices Festival. ↩