Sometime around 1520 Ferdinand Columbus, second son of the famous Christopher, wrote to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (Charles I of Spain), requesting money for a universal library—a place, Ferdinand explained, where “all the books will be gathered, in every language, and concerning all the sciences and the arts that can be found both in Christian and in non-Christian nations.” Attached to the court since childhood, Ferdinand had accompanied his father on his calamitous fourth voyage as a teenager, but then devoted himself to a life of scholarship and diplomacy. Crisscrossing Europe on missions for the crown, he amassed more than 15,000 books and 3,200 prints, the most complete repository of verbal and visual information in Europe.

The five hundred livres that Charles V eventually coughed up aside, this extraordinary venture was made possible by Ferdinand’s own fortune, which is to say by the New World holdings granted to his father, which is to say by colonial crimes of the first order—theft, slavery, genocide. Ferdinand himself seems to have been a thoughtful man, and it is easy to be moved by the sublimity of his aspirations. It is also easy to condemn the atrocities and cultural obliteration on which they depended. What’s difficult is holding both in your mind at the same time.

This is the essential quandary William Kentridge has spent his career voicing through art: How do we reckon with both the radiant promise of knowledge and its effects as an engine of subjugation and destruction? Is there a border where the desire to know becomes the will to control, or do they slide down the slippery slope hand in hand? Kentridge, who was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1955, the son of anti-apartheid lawyers, came of age within a vividly brutal example of pseudoscientific thinking run amok. The lessons he took from it were both historically specific and philosophically broad—chief among them: Nothing is as simple as it looks.

The South African literary scholar Stephen Clingman opens his text for the recent Kentridge retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts in London with images of his thirteen-foot-tall sculpture World on Its Hind Legs (2009). Seen head on, it looks like a giant ink drawing of a globe perched on a pair of inverted radio masts. Step to the side, however, and the amiable, cartoonish globe reveals itself as a concatenation of black metal jutting into space with the confident aggression of a Mark di Suvero sculpture or a guy manspreading on a subway seat. Both views are real; it just depends on where you stand.

Such eye-grabbing theatrics and tangible metaphors have made Kentridge one of the twenty-first century’s most visible artists. In addition to being represented in just about every relevant museum you can think of, he has delivered the Norton Lectures at Harvard, produced operas for the Met, and designed espresso cups for Illy. In the past year he has been the subject of two major retrospectives—one at the RA and another, “William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows,” at the Broad in Los Angeles and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; his large-scale music/theater works have been presented in Los Angeles, Paris, Johannesburg, Madrid, and Vienna; Steidl in Germany has published a catalogue raisonné of his early prints and posters (weighing in at a hefty ten pounds); Seagull Books in Kolkata has released an artist’s book of found phrases he collects in his studio; and Marian Goodman Gallery recently hosted the New York premiere of his new multichannel video installation, Oh to Believe in Another World.

There is, to be honest, something disconcerting about this wild productivity across so many different mediums and so broad a swath of the globe. We expect that kind of thing from artists such as Takashi Murakami or Kaws, because commercialism is core to their content. But Kentridge, with his button-down collars and pince-nez, his lectures on Plato and Mozart, presents as the kind of avuncular, old-school artist who can utter a phrase like “There’s an entire erotics of etching” (as he did in one of his Norton lectures) and really mean it. Again, both views are real: somehow he has built a global brand and a local industry (a formidable Johannesburg-based infrastructure of printers, foundries, musicians, dancers, and other collaborators) on a foundation of muddling about in the studio with a piece of charcoal in hand.

The work that brought Kentridge to international attention was the series of short films collectively called Drawings for Projection. The first, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris (1989), is an eight-minute animated saga of capitalist exploitation, adulterous desire, floods, and metamorphosis. Viewers were caught by the dreamlike transmutation of characters and objects, by the doubling of personal and political actions, and by the film’s handcrafted, even disheveled, look. Most predigital animation used clean lines and flat color on transparent cels. Kentridge worked instead with charcoal on paper—drawing, erasing, and redrawing on the same sheet, photographing each successive state as a frame for the film. Scenes would be built up stroke by stroke and then eradicated by smudging and erasure, but charcoal never fully gives up the ghost—erased marks remain visible as a kind of smoky wake, so the past is never fully out of view.

Advertisement

It was an effective but absurdly time-consuming process: a nine-minute film would take, he says, ten months to produce, and since it was impossible to keep the camera and paper in perfect alignment over that time, the films have a jerky quality that, together with the title cards spelling out plot points, recalls silent film. The Drawings for Projection were contemporary yet old-fashioned, aesthetically sophisticated but kitchen-table-craft-project crude in terms of technique. Part of the magic was the guilelessness: you can see exactly how it was done.

In the early 1990s, when the films began to be shown internationally, South Africa was still an international pariah from a human rights perspective and an irrelevance from an art world perspective. For European and American gallerygoers, Kentridge seemed to come out of nowhere.

Print catalogues raisonnés are of interest mainly to specialists, but Prints and Posters 1974–1990 has the broader attraction of offering a window into Kentridge’s development in the fifteen years leading up to Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris. Assembled by Warren Siebrits, it is an impressive archival feat—329 entries and 684 pages spread over two hardback books (the first documenting the final state of each work, the second dedicated to proofs and variants). Since every print is accompanied by a statement from the artist, the catalog constitutes an artistic autobiography of sorts.

The first entry is Kentridge’s campaign leaflet from 1974 for his student council candidacy during his first year at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. A Letraset and clip art confection of tongue-in-cheek Victorian pomp, it bears his name on one side and his platform on the other, promising “rational and articulate leadership, and a healthy disrespect for what most students get out of a university such as ours.” He was there to study political science, but activist theater and art emerged as his true callings. In the Seventies he made lots of posters for the various plays and political projects he was involved in. He also dabbled in linocut but writes that he felt his “applied art—images in the service of something else . . . are far more interesting images than those where I was thinking of myself simply as an artist.”

Yet Kentridge’s habits of hand and eye have proved remarkably consistent. A 1976 linocut, made after an old photo of his father as a child with his family on a beach, displays the same flat silhouetting in combination with skittering detail that can be found throughout his subsequent career. Equally indicative of things to come are the hints of interpersonal drama (the two boys and their childminder look to the side while the father stares glumly ahead in his three-piece suit and hat) and the clarifying detail that pins the image to a particular time, place, and social milieu (a sign for Muizenberg, a Cape Town beach popular with Jewish South Africans, giving the year, 1933).

Like many artists, especially those climbing a learning curve, he ran repeated test prints of the linocut to check progress as he cut the block. Unlike many artists, he kept those proofs, and the catalog reproduces eleven states and variants. (Three of these appear in the “Shadows” catalog.) We see the father’s head grow a body, and can mark the arrival of one son, then the other, and finally their nanny. “I had no thought of animation,” Kentridge writes,

but after each few cuts I would do another test…. In the end‚ there was a whole series of developing images, almost like a flip book that the image would form itself, much as the drawings did in the early animated films, such as Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris.

Across the remaining three hundred–plus entries, we watch Kentridge’s allegiances and technical experiments flow in various forms. There are posters for children’s theater productions and film festivals in support of political causes; a lithographic suite of interior scenes channeling Max Beckmann; a series of fifty-four etchings of interior scenes replete with Francis Bacon distortions, tulip chairs, and a furious cat.

That etched cat can be seen in William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows, along with the descendants of that cat—all spiky fur and raging eyes—that crop up again and again in both retrospectives, taking form in fuzzy charcoal or cast bronze, part of the iconographic troupe that Kentridge has assembled over the years. There’s the stovetop espresso pot, the beagle-like rhinoceros, the megaphone (with and without legs), the tree—objects that arose in some specific context, serving a specific purpose, but then stayed on to play other roles.

Advertisement

Since much of Kentridge’s art exists in editions, there is some duplication between the Royal Academy and Broad shows as represented by their catalogs. (I was unable to attend the exhibitions themselves.) The chief difference lies in approach. Shadows includes an assortment of texts: essays by curator Ed Schad, South African writer Zakes Mda, and artist Ann McCoy; a conversation between Kentridge and film editor Walter Murch; and the transcript of a Kentridge lecture about drawing as performance. The RA catalog is more consistent in voice and coherent in the story it tells. Each in its own way serves as a generous introduction to Kentridge’s work and its concerns.

The Drawings for Projection and later film and video installations using sets, puppets, and human actors were prominent in both exhibitions and suffer more than static objects in the transition to books. (The RA catalog does include links to a media-viewing app, though I was never able to get it to work.) The reader is left with film stills and reproductions of the ingredients from which the films were made—charcoal drawings, model theaters, props, and mechanical contraptions. But given Kentridge’s fascination with mutability and reuse, this is not as problematic as it might be.

For later films he assembled characters from tools and other materials, with a child’s gift for recognizing the animated figure inside the inanimate object—the calipers’ legs just waiting for a head and a skirt. (“Anything hinged at the center suggests legs…. We don’t impose an anthropomorphism,” he observed in a lecture. “We are unable to resist it. These are performances demanded by an object.”) As readers we lose the plotlines, soundtrack, and timing of the film, but the implicit motion remains, even in still drawings like the charcoal gravedigger from Other Faces (2011), whose jittery flux of erased and redrawn contours suggests a dirtier version of Giacomo Balla’s Futurist dachshund.

For Kentridge, drawing is less a tool for freezing an event than a means of getting a ball rolling. Charcoal smoke on paper can assemble itself into a typewriter to be photographed for a film; the charcoal typewriter may find second life as a sculpture; the typewriter sculpture may, when viewed from a different angle, reveal a tree. Everything is mutable and provisional.

He was attracted by charcoal “because of the indeterminacy of the point,” he says, but rarely is he content to leave it alone. Sketchy observation runs up against the Euclidean traces of analysis and measurement. The expansive charcoal gestures describing the waterfalls and wetlands of his Colonial Landscapes of the 1990s are overlaid with tidy red pencil lines and circles, like the amendments of some tetchy superego. The charcoal rocks and trees of Small Koppie (2013) were drawn on old ledger pages under the printed header “Central Administration Mine Cash for the Month Of.” Two different systems for estimating value occupy the same space: land versus landscape, principle versus instance, sense versus sensibility.

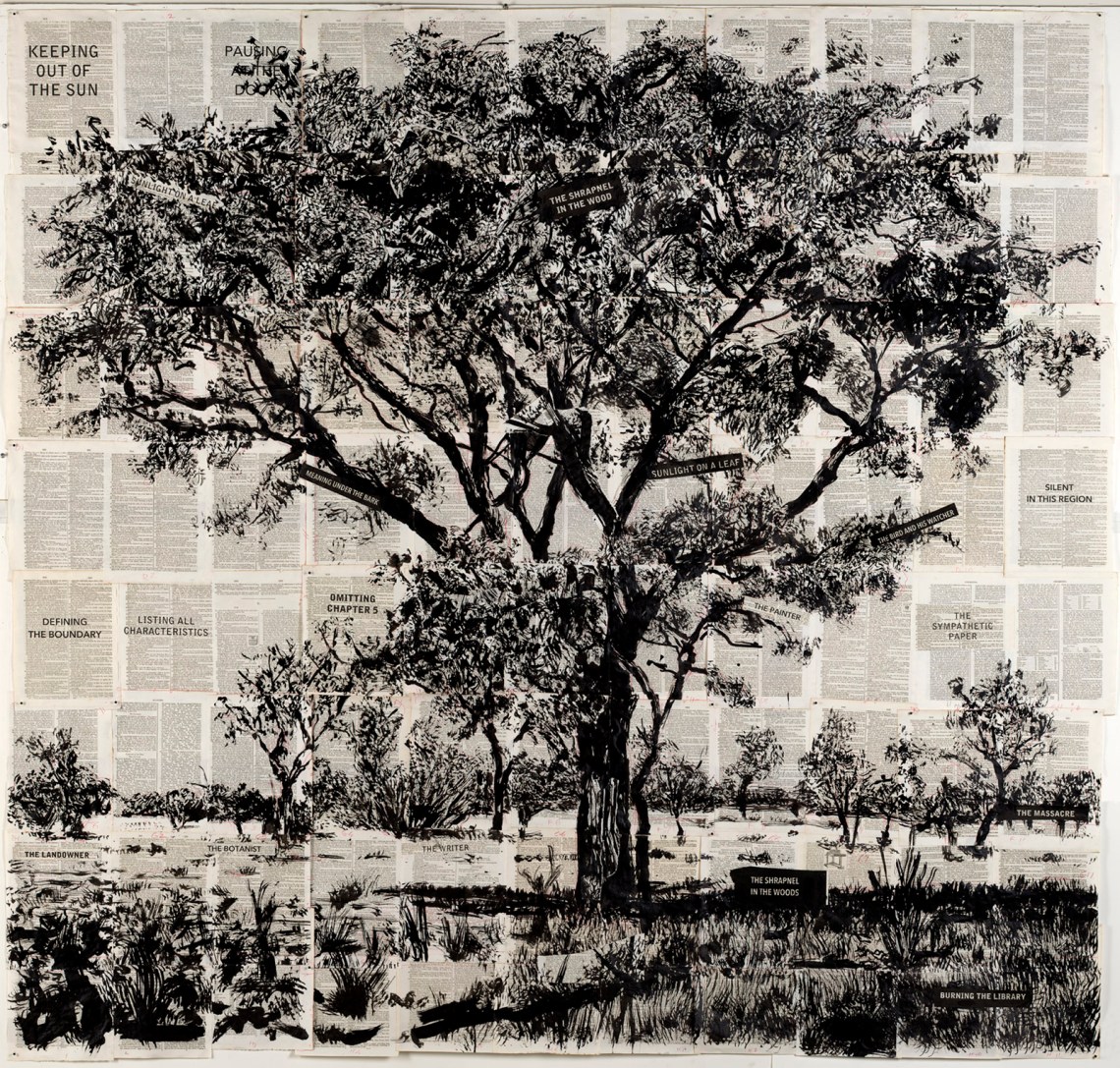

In The Shrapnel in the Wood (2013) a brushy tree of India ink stretches over a grid of eighty-eight pages from the 1826 Universal Technological Dictionary, or Familiar Explanation of the Terms Used in All Arts and Sciences. (Kentridge identifies the dismembered source publication in his description of medium.) But the binary opposition is complicated by the enigmatic cutout phrases decorating both tree and dictionary: “KEEPING OUT OF THE SUN,” “SILENT IN THIS REGION,” “THE SYMPATHETIC PAPER,” “THE SHRAPNEL IN THE WOOD,” and more.

These linguistic slivers have become increasingly prominent in Kentridge’s art over the past decade. You find them scattered across the pages of his ink drawings and films, as if the terse silent-film plot cues in Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris had gone on to get an MFA in creative writing. Sometimes they have clear relevance—“Where are our former kingdoms” crops up in his video installation Kaboom!, about African sacrifices in World War I—but more often their significance is oblique.

His performance work Waiting for the Sibyl (2019) offered a classical precedent for these verbal orts: the Cumaean Sibyl, who wrote her prophecies on oak leaves and left them for recipients at the entrance to her cave, whence they were naturally scattered by the wind. Kentridge saw it as an allegory about fate and chance and the impossibility of knowing which is which. In his studio he has taken on the role of Cumaean gleaner, gathering windblown verbiage for use as a combination archive and game of chance. “I have a book that I call ‘Words,’” he told Walter Murch, “in which I write odd phrases while reading…. Later, I take them out and spread them on a table while I am working on a project. I look for echoes between the phrases and what I am doing.”

The slender hardback Words: A Collation is a distributable version of this notebook. Phrases—each printed out on its own scrap of paper, like a cookie fortune—are scattered across the spread. Some get a page to themselves (“The silence roars”), others pile in together. Some have the second-person bossiness of Jenny Holzer truisms (“Feast your eyes on your childhood”), others are quietly personal (“My father’s books”). Each is tagged with a letter and number in red pencil, directing it to a particular page and section in the book—assignments made “neither randomly nor with a clear agenda,” Kentridge writes, but by some affinity left to the reader to ferret out. (The last section is declared to be a multipage appendix of “surplus” statements randomly arranged, though some of these also appear in earlier sections.)

There are many precedents for this kind of thing, of course, from Dada to Fluxus to Magnetic Poetry kits. Kentridge says he sees them as “passages of which one wonders, not so much what the author meant, but what could they mean.” This works to a point, but the balance is tricky. Slip too far in the direction of identifying sources and you’re instructing, steering the audience to particular ends; slip too far the other way and the words lapse into facile profundity. The “shrapnel in the wood” phrase, he tells Murch, was a Swedish boatbuilder’s warning to avoid German lumber, which even today sometimes comes from trees blasted with shrapnel in World War II. It’s a background story far richer than the vague poetry of the words all on their own. For Kentridge, I suspect, such eclectic fragmentation provides a kind of safety net—a diversified portfolio of ideas that spreads the risk of any given theory of everything, which is where politics reenter the equation.

When the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra in Switzerland commissioned Kentridge to make a film for a concert performance, he chose to work with Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony, whose premiere took place nine months after the death of Stalin. The degree to which it is a commentary on Stalin, who alternately lionized and terrorized the composer, is the subject of debate. In The Noise of Time (2016), his novel charting Shostakovich’s tacks in response to Soviet political winds, Julian Barnes noted that confusion about the composer’s intentions may be “highly frustrating to any biographer, but most welcome to any novelist.” Or any artist.

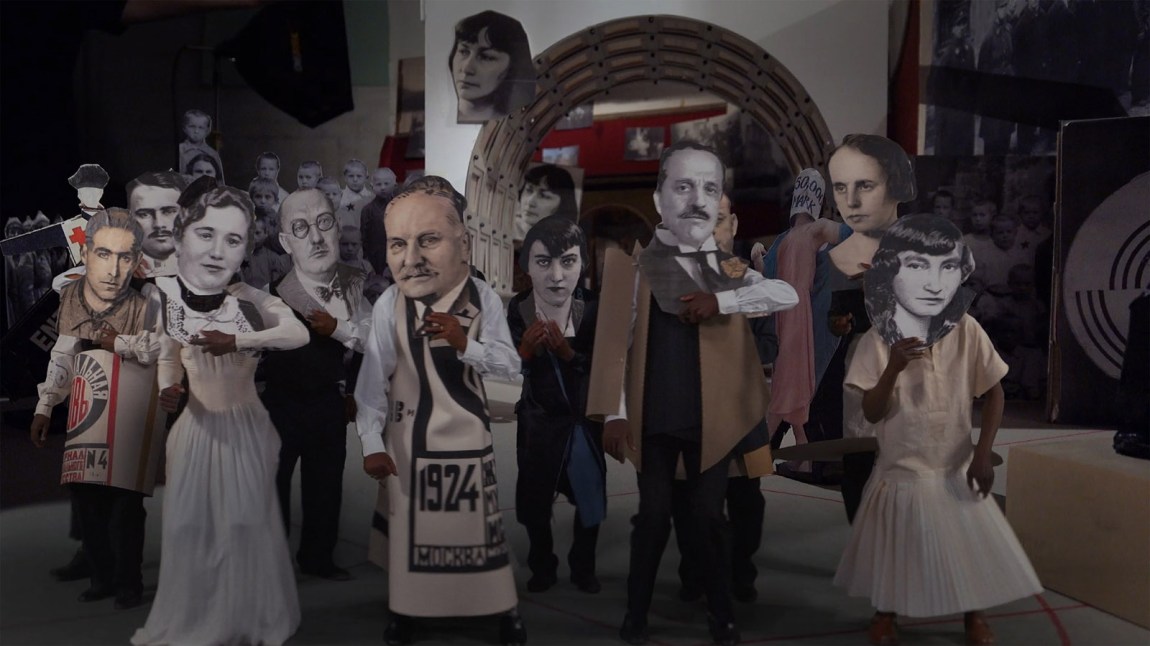

The video installation version of the film, Oh to Believe in Another World, recently on view in New York, is a shape-shifting tour de force in which figures from Soviet history—Stalin, Lenin, Trotsky, Shostakovich, Mayakovsky, Lilya Brik, and composer Elmira Nazirova—are represented by dancing hardware puppets (rusty scissors in trousers, wrenches in pleated paper skirts) and by human actors dressed in imitation of the assemblage puppets, with a nod to Oskar Schlemmer. Historical footage of Soviet life is intercut with dancing puppets, snippets from Mayakovsky poems (“WE’LL MAKE SHOES FROM THE SKY”), and humans holding famous Soviet faces in front of their own. Big and small collide as the actors are shrunk down to fit into the tabletop “museum of Soviet history” Kentridge built in his studio. The artifice is always visible—we can see Black hands holding those white faces, and we aren’t really fooled by the paper museum.

Kentridge, champion of the fragmentary and provisional, has a natural affinity with Shostakovich, who was denounced (probably at Stalin’s behest) for the “chaos” and “muddle” of his music. Though Kentridge has a fondness for Dada and Shostakovich made strategic use of dissonance, neither chaos nor muddle is the net effect of either’s work. Oh to Believe in Another World, like the Tenth Symphony, leaps between scattered dissolution and anthemic coherence, always keeping both in play, like an operatic version of World on Its Hind Legs.

Clingman opens his essay with Kentridge’s question “What happens at the edges?”—a query that might have been voiced by Ferdinand Columbus’s father, swiftly followed by the fifteenth-century equivalent of “and how can we monetize it?” Kentridge wants us to be aware of those old imperial edges, and of the ongoing political problem of who decides which people constitute the center and which the periphery, but more broadly he wants us to see how fungible and impermanent edges can be. Thus his fondness for visual tricks like the anamorphic sculptures, where the illusion and its betraying mechanism cohabit in the brain.

“I am interested in a political art,” he has written, “that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain endings. An art (and a politics) in which optimism is kept in check and nihilism at bay.” Perhaps this explains how he can be drawn to movements like Dada—disruptive, inconvenient, inconsistent—while successfully coordinating the large enterprise needed to produce his art. Or how his mistrust of encyclopedic thinking makes peace with his instincts as an archivist. (One could view the vast print catalogue raisonné project, still anticipating four installments, as a kind of metacommentary on the obsessive but inevitably incomplete documentation of art—a parallel to his Norton Lectures, in which he argued convincingly against the wisdom of convincing argument.)

Thumbing through the retrospective catalogs reminds one of how peculiarly antiquated Kentridge’s visual world is. The logic of economic exploitation is invoked not by Excel spreadsheets or Bloomberg terminals but by copperplate script in letterpress ledgers. The old dictionary pages may have been chosen because they exert more authority than a Wikipedia entry, or more likely because he likes the look of knowledge as it paraded through the seventeenth to early twentieth centuries. His films mimic the charming hokeyness of Georges Méliès’s fin de siècle conventions. Oh to Believe in Another World has the same jittery quality as the charcoal drawing films, despite its use of contemporary technology.

That all this doesn’t come across as merely twee has to do with the fact that Kentridge is always disrupting the form’s original purpose (it’s very hard to glean useful knowledge from book pages now reworked with charcoal and ink), but also with the work’s grittiness, both literal (charcoal, etching, etc.) and metaphorical. From those first entries in the catalogue raisonné we see Kentridge attaching his hand and mind to the artifacts of history—a family photo, Victorian printed oddments. When he wrote that he was at his best with “images in the service of something else,” he was not wrong, though the nature of that “something else” has changed from posters for contemporary plays to the excavation of historical moments.

History, Kentridge wants us to understand, is like his sculptures, or his films, or his drawings on concatenated book pages. There may be an instant where it all comes together and makes sense, but it’s we, not the data, who make the sense—“make” as in “manufacture,” as in “making it up.” Our brains are hardwired to find meaningful connections among any sensory inputs. We can’t help it. (This is a game at which art critics, like gamblers, habitually overestimate their skills.)

To the best of my knowledge, Kentridge has never mentioned Ferdinand Columbus’s library, but just as its creation represents the Enlightenment aspirations so central to Kentridge’s dilemma, its saga embodies the problems of fate, entropy, and historical narrative. Before Ferdinand died in 1539 he left detailed instructions for how the library should be looked after, but over time the books were divvied up and the print collection lost. An inventory of the prints, however, survived in the Colombina Archive in Seville, along with a nineteenth-century copy in the British Museum, where, in the early 2000s, scholars led by Mark McDonald set about virtually reconstructing the collection by aligning the inventory entries with prints still known today.

The resulting database and publications were a remarkable achievement given that many prints from that time have failed to survive at all, that Ferdinand’s inventory included no images, and that the priorities of sixteeth-century catalogers were very different from those of later art collectors and historians. (For starters, their primary indexical categories were not the name of the artist and the date, but the size of the paper, the subject, and number of figures.) McDonald managed to fully identify about half; the rest remain ghostly half-presences—“Round Foliage” or “A Standing Saint (Dominic?).”

One of Kentridge’s winning film tricks involves simply running the action in reverse so that thrown paint gathers itself neatly in the can, the torn drawing reassembles itself into flawless coherence, and entropy loses its endgame. It’s incredibly satisfying to watch precisely because it’s not the real world. The real world is that of Ferdinand’s print collection, where not all losses are recoupable and absences crowd around every piece of knowledge. “Can one find the truth in the fragmented and incomplete?” Kentridge asked in the program notes for a 2018 production of The Head and the Load, the theatrical cousin of Kaboom! “Can one think about history as collage rather than narrative?” Let’s hope so, because really, it’s all we have.