What kind of life should an artist live? In a way this is a nonquestion, in that the only serious answer is whatever life might facilitate the production of art. But it’s a question that presented itself to me with maddening insistence as I read the German filmmaker Werner Herzog’s extravagantly titled new memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All. Herzog is a figure of such storied romance and such implacable charisma that to read about his life is to feel that you yourself have been going about the thing all wrong—certainly if you are any sort of artist, and perhaps even more so if you are not.

As I turned the pages of Herzog’s book, and was shunted from one insane episode to the next, I was gripped by the tightening conviction that my own life was, by comparison, barely a life at all. I was not born into a country at war with the world. I have never been shot, or stabbed my own brother. I have never worked as an arena clown riding bullocks at a Mexican rodeo. I have never journeyed from Berlin to Paris on foot as a kind of magical-realist intervention to forestall the death of a beloved mentor. I have never cooked and eaten my own boot in fulfillment of a lost wager. I have never hauled a 320-ton steamship over a hill in the Amazon rainforest. I have never fallen into a crevasse while mountain climbing in Pakistan. I have never taken a trip to Plainfield, Wisconsin, with the intention of digging up the corpse of Ed Gein’s mother. I have never been bitten on the face by a rat while delirious with dysentery in a garden shed in Egypt. I have never swapped my only good shoes for a bathtub filled with fish in order to feed a film crew in the Peruvian jungle. I have never even met—let alone threatened to murder as a means of extracting a powerful cinematic performance from—the dangerous madman Klaus Kinski. And more’s the pity, I have to say—on all counts, with perhaps the exception of the rat bite/dysentery scenario.

I will admit that this is an eccentric and perhaps foolish way of going on about a legendary filmmaker’s autobiography, but such is the relentless action of Herzog’s life, and his sheer conviction and magnetism in narrating it, that it’s difficult to avoid reading Every Man for Himself as an argument for how an artist should conduct himself in the world. From the moment he learned to walk, it seems, Herzog was striding stoutly down from the Bavarian hills of his childhood in determined pursuit of experience, out of which has arisen his vast and variegated (and, it has to be said, radically uneven) body of work.

The memoir is more focused on Herzog’s voluminous opinions and enthusiasms, and on discrete anecdotes (fraternal stabbings, shoe eatings, and so forth), than on providing a straightforward narrative of his life, but a basic sense of his trajectory does emerge. A fair number of pages are devoted to his childhood during and just after World War II. His father was almost entirely absent, a “marginal figure” who talked endlessly of a vast encyclopedic work he was supposedly engaged in writing, not one word of which he ever produced. Herzog’s mother, a biologist whose Ph.D. thesis was on the hearing of fish, took him and his siblings to live in a remote, mountainous region of Bavaria, far from the Allied bombs, where they were raised in extreme poverty with no running water and precious little food. His deepest memory of his mother, he writes, is of him and his brother clutching at her skirt, begging for something to eat:

She said, perfectly calmly: “Listen, boys, if I could cut it out of my ribs, I would cut it out of my ribs. But I can’t. All right?” At that moment, we learned not to wail. The so-called culture of complaint disgusts me.

It would be absurd to say that Herzog does not come across in this book as a thoughtful man—there are times, in fact, when he reads like nothing so much as a wayward eighteenth-century philosopher—but his particular style of thoughtfulness almost entirely precludes our contemporary mode of self-analysis. On the question of why he has lived this restless life, and what its relationship to the films might be, he has almost nothing to say. And perhaps there is nothing much to be said: he has lived in this way because it was how he could become the man who made his films. But there is something resolute and methodical about the wildness of Herzog’s life, as though he were practicing a kind of mindful chaos. And the strange drama of it all seems always to have been inseparable from the making of the films.

Advertisement

Of his private life in maturity—of his three marriages, and his three children—Herzog has comparatively little to say. Such material is mostly confined to a brief chapter, late in the book, with the startlingly utilitarian title “Wives, Children.” He dampens, at the outset, any expectation the reader might have of getting anything juicy: “To speak about my wives violates my natural discretion; I’d just like to say that all the women in my life, without exception, were extraordinary: gifted, self-motivated, warm-hearted, and wise.” He adheres to this register throughout, as though providing generous promotional blurbs to his wives and children. There is a certain amount of reflection on his relationship with his current spouse, the artist Lena Herzog, but it’s pretty anodyne stuff. There were two previous marriages, to Martje Grohmann and Christine Ebenberger, with each of whom he has a son, and a relationship with the actress Eva Mattes, with whom he has a daughter; of these he admits that his commitment to his work, and the life that arose from it, made him a less than ideal partner. The chapter is, on the whole, as brusquely unreflective as its title suggests.

One of the more illuminating moments in the book, in fact, comes when Herzog most explicitly rejects the value of self-analysis. He is recalling an early episode of his personal mythology: in his teens he worked as a parking attendant at Munich’s Oktoberfest. During calmer interludes, when he wasn’t forced to wrestle car keys from the hands of shit-faced Bavarians, he developed a strange practice that blurred the boundaries between bored-teenager stunt and high-concept installation art. He would rig up a vehicle in his charge, locking the steering wheel to one side using a hooked rubber cable and pressing down the accelerator with a heavy stone, so that it would drive around the meadow in tight circles, unmanned and at speed. “I usually had at least one driverless car going endlessly around and around, sometimes two,” writes Herzog. (He doesn’t say how he got them to stop.)

This reminiscence recalls (or foreshadows) one of the most memorably strange moments in his filmography: the lengthy sequence in Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970) in which a group of dwarves rig a van to drive in circles around a courtyard, climbing in and out and performing hazardous maneuvers with a picnic blanket like matadors taunting a bull. Herzog acknowledges the Oktoberfest stunt as the source of this scene, but refuses to venture what it might mean to him, or why it might have impressed itself so firmly upon his mind. (I can think of at least one other early film of his, 1977’s Stroszek, that prominently features a driverless vehicle going around in circles, and he says there are others.)

And this is where things get interesting, because he turns the moment into a brief and startlingly vicious broadside against the good ship psychoanalysis and all who sail in her. These insistent motifs—the elements from the “personal depths” that pop up here and there in his stories—must, he says, be left unmolested by analysis:

I’d rather die than go to an analyst, because it’s my view that something fundamentally wrong happens there. If you harshly light every last corner of a house, the house will be uninhabitable. It’s like that with your soul; if you light it up, shadows and darkness and all, people will become “uninhabitable.” I am convinced that it’s psychoanalysis—along with quite a few other mistakes—that has made the twentieth century so terrible.

With psychoanalysis, as with gambling, the house always wins, so it’s easy to imagine Freud responding to this denunciation by leaning back in his creaking office chair and saying, “Tell me more.” But what’s interesting about Herzog’s book is not so much what he might be refusing to think about as his refusal of a particular way of thinking. I feel, with a terrible and exhilarating certitude, that if I were to ask Werner Herzog whether on some level he thought of himself as a car going endlessly in circles with no one at the wheel, he would narrow his pale eyes and call me a dangerous half-wit, and that he would be right to do so. In the book’s final pages he returns to this theme (or anti-theme) with an impatience that led me to suspect an editor’s queries, fruitlessly prompting Herzog to reveal more of his private life:

What does my average day look like? Who are my friends? What sort of life do I lead? I have trouble describing myself because I have a vexed relationship with mirrors. I look in the mirror when I shave so I don’t cut myself, but that shows me my jawline, not my person. To this day, I couldn’t tell you what color my eyes are. Introspection, navel-gazing, is not my thing.

The reason for this personal taboo against self-scrutiny has to do, in one sense, with a belief that were he to analyze himself too thoroughly, he might eradicate (rather than deepen) the mystery that lies at the source of art. Herzog is not interested in psychology as such; he is concerned with the soul—and maybe even with the Soul of Man. “Psychoanalysis,” as he put it in one interview, “is no more scientific than the cranial surgery practiced under the middle-period pharaohs, and by jerking the deepest secrets out into the open, it denies and destroys the great mysteries of our souls.” (You don’t have to be a Freudian, or even a pharaonic cranial surgeon, to feel compelled to point out the strangeness of a criticism that condemns a practice as both completely unscientific and disastrously, paradoxically effective.)

Advertisement

These kinds of sudden sideswipes are Herzog at his best, by which I mean his most irreducibly Herzogian. This is as true of his films as it is of the memoir. In Fireball (2020), a documentary he made with the volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer about the literal and cultural impact of meteors, there is a wonderful moment where Herzog’s camera roams through the desolate streets of Chicxulub, the Mexican town at the center of the vast impact site of the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. A tracking shot takes us up a particularly depressing side street, where two dogs are nosing around the corpse of a third. Herzog’s unyieldingly Bavarian voice addresses the scene: “The dogs here, like all dogs on this planet, are just too dim-witted to understand that three quarters of all species were extinguished by the event that took place right here.” If I had to explain why I laughed out loud at this moment, I would probably say that it had something to do with its gratuitousness. Why address this ancient apocalypse by casually insulting a couple of dogs in a crummy Mexican coastal hamlet (and also dogs as a species)?

But apparent gratuitousness, and especially gratuitousness involving animals, is something of a Herzog hallmark, and part of what makes his work so vital. His particular art, with its interest in human absurdity and the otherness of nature, has always been well served by animal performances. There is the bizarre moment in the underrated Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009), Herzog’s funniest film, in which the camera gets distracted from the doings of Nicolas Cage’s rogue cop and lingers lengthily, inexplicably, on a couple of charismatic iguanas. There’s the famous final shot of Stroszek, in which a chicken jitterbugs to a rousing blues track. There’s the even more famous final shot of his masterpiece, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), in which Kinski’s deranged conquistador stands on a sinking raft in the Amazon surrounded by monkeys, pontificating on the dynasty he will found with his daughter to rule the continent. (“Who else is with me?” he asks the indifferent monkey he holds in one hand, before flinging it contemptuously away.) There is the sublime flip side of that scene, the final shot of My Best Fiend (1999), Herzog’s documentary about his tumultuous collaboration with Kinski, in which the actor stages an ecstatic impromptu performance with a butterfly, allowing it to alight now on his hand, now on the curve of his ear.

Though he is often a subject of parody, it is rarely noted how powerfully amusing—how seriously funny—Werner Herzog is. In a way that strikes me as characteristically German, he is often funniest when he’s at his most resolutely serious. This ability to be funny without doing anything so frivolous as joking is something English speakers tend on the whole to miss about Germans, and which seems to me to be a cause of the widespread (and richly ironic) Anglophone delusion that Germans lack a sense of humor.

At one point in the memoir, for instance, Herzog relates an anecdote about receiving a call from a curator at the Whitney Museum who wanted to know whether he would consider making an original contribution to their upcoming biennial. Herzog told the curator that he did not think of himself as an artist, that this term would be “better applied to pop singers and circus performers.” The curator asked what he considered himself, if not an artist. “I said I was a soldier and hung up.”

It’s a funny moment, and one in which some measure of self-irony is obviously in play, but it’s also clear that the job description Herzog provides is meant quite seriously. This is not the first time in the book that he has characterized himself as such: “I always wanted to defend outposts others have already abandoned,” as he puts it in a brief foreword. And he is certainly possessed of a soldier’s idealized fearlessness and steadfastness. One of the memoir’s most striking aspects is the sheer number of acts of violence and accidental injuries it relates. He is hit in the eye with a missile during a childhood chestnut battle, causing him to fall from a rooftop onto a pile of agricultural machinery, breaking his forearm. He is kicked in the face by a butcher’s apprentice during a soccer match, receiving injuries that require fourteen stitches. He sustains two damaged vertebrae and a detached collarbone in a botched display of braggadocio on a ski slope near Mont Blanc during a film festival. As a young man he leaps from a snow-covered rooftop and mangles his ankle while playing with the children of a family he lives with in Pittsburgh.

One of my favorite moments in the book comes when Herzog is briefly dilating on his relationship with his older brother Till, which is marked, even as they both approach their eighties, by a kind of rough, jokey intimacy. At a family reunion at a restaurant in Spain, Herzog becomes aware of smoke, and of a slight prickling at his back. Till, it turns out, has set his shirt on fire with a cigarette lighter. “I tore it off, and everyone was aghast,” he writes, “but the pair of us laughed loudly at the joke that didn’t seem funny to anyone else.” Here, and at several other points throughout the book, I found myself murmuring in a poor approximation of Bavarian-accented English the words “Hi, I’m Werner Herzog, welcome to Jackass.”

Among the more memorable pieces of film Herzog has been involved in demonstrates this blasé attitude toward peril. The clip, “Werner Herzog is SHOT during interview,” is on YouTube, and if you haven’t seen it, I cannot recommend it highly enough. During a BBC interview, conducted outdoors in the Hollywood hills with the film critic Mark Kermode, Herzog is interrupted by a loud noise. It soon becomes clear that he has been shot in the stomach by a lunatic with a gun on a nearby veranda. Kermode is aghast, and insists that they stop the interview so that Herzog can get help, but Herzog is dismissive. The bullet has penetrated his leather jacket, but the wound itself is nothing to speak of. “It was not a significant bullet,” he says. In a subsequent interview, published in the book Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed (2014), he made it clear that he was still angry about the incident—not at the man who shot him, but at the TV crew for making such a fuss about it. “I would have continued with the interview,” he said, “but the cameraman had already hit the dirt. The miserable, cowardly BBC crew were terrified and wanted to call the cops, but I had no interest in spending the next five hours filling out police reports.”

I’m probably making Herzog sound more cantankerous than he actually is, and more eccentric too. It’s not that you’d exactly call him affable, but it’s striking how seldom he has anything approaching a bad word to say about anyone, BBC milquetoasts aside. He does, it is true, have a great many bad words to say about Kinski, but a full and lavish appraisal of the actor’s rabid sociopathy does not preclude—and in fact can seem to be ultimately in service of—a frank admiration for his greatness as a performer. (Herzog by no means glosses over the revelations about Kinski’s sexual abuse of his daughter Pola, which he has spoken about elsewhere, but he doesn’t exactly dwell on these horrific facts either. “Should we remove the paintings of Caravaggio from churches and museums,” he asks, “because he was a murderer?”)

The book’s title is, as he admits himself, a pretty misleading one: he is constantly going on about how this or that cameraperson or producer, or this or that friend or sibling or ex-wife, is an invaluable person without whom he couldn’t have even begun to do what he did. (With a title as great as Every Man for Himself and God Against All, though, it hardly matters whether it’s accurate; its obvious greatness as a title for anything is justification enough. It wasn’t appropriate as the German-language title for his 1974 film The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, either, and it was no less great then.) Although Herzog’s life is preposterously overstuffed with dramatic events, it never reads as mad or incoherent. There is a productive tension, at all times, between chaos and control; just as in his films, he is often focused on the darkness and meaninglessness of creation but is never quite seduced by them.

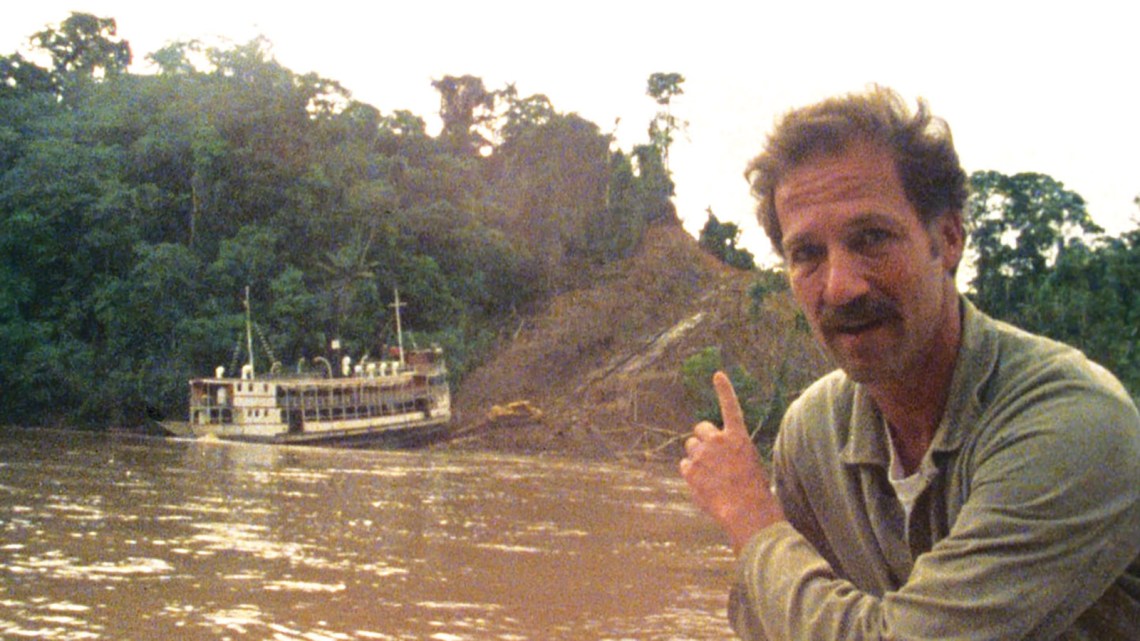

Herzog has an almost fetishistic commitment to difficulty, if not quite for its own sake then certainly as a means to an end: if something is worth doing, it’s worth doing in the hardest possible way. His film Fitzcarraldo (1982), about an Irish rubber baron hell-bent on building an opera house in the middle of the Peruvian jungle, centers around the protagonist’s orchestration of a seeming impossibility: dragging a steamship over a hill separating two parallel rivers. His film is famous less for being great—despite the sheer scale of its efforts, it never quite is—than for how great it is to think about, which is why Burden of Dreams (1982), Les Blank’s documentary about the film’s lavishly thwarted production, is more interesting and fun than the film whose creation it documents.

Herzog insisted on shooting in a remote part of the jungle, rejecting the option of setting up the shoot close to the town of Iquitos, with its hotels and its airport. In the memoir, he makes the reasonable-sounding argument that the flat, sea-level terrain around Iquitos was simply not appropriate for the story he wanted to tell. But in Burden of Dreams, he insists that the remoteness of the location is itself the appeal, that the sheer isolation and inherent challenge of the place will bring out some special quality in the actors and the crew that would otherwise be inaccessible.

Herzog’s attraction to Kinski—perverse but undeniably fruitful; they made five films together—is the ultimate manifestation of this commitment to difficulty. From the moment of his first appearance in Every Man for Himself, he is for Herzog a kind of unholy fool, embodying in his ravening villainy a pure and profane madness. The story of their first encounter will be familiar to anyone who has seen My Best Fiend. At age thirteen, Herzog moved with his mother and siblings to a tiny apartment in Munich. One of the building’s other inhabitants was Kinski, then a struggling twenty-six-year-old actor, who was taken in rent-free by the kindly landlady, Clara. Kinski, starting as he meant to go on, rewarded her charity by behaving monstrously toward her and everyone else around him:

As an opponent of all forms of civilization, he…disdained silverware. At the table for the lodgers, he ate with his hands, head over his plate, scooping it up. “Eating’s a bestial act,” he yelled at the frightened Clara, and when it one day dawned on him that she really did cook with margarine, not butter, he smashed plates in the kitchen and hurled an iron casserole through a closed window.

After enumerating a selection of such incidents, Herzog states that he himself, child though he was, was not in the least afraid of Kinski. “To me,” he writes, “he was a force of nature; it was like watching the devastation wrought by a passing tornado.” This is a cliché, of course, but it’s also a revealing one. Kinski was known for his violent temper and for being an extraordinarily abusive and erratic presence, on sets and in his personal life. He emerges, in Herzog’s portrait, as both an avatar of impersonal violence—like the Amazon, or the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs, or the grizzly bear that killed Timothy Treadwell in Grizzly Man (2005)—and a wild creative force to be literally directed toward the purpose of art.

“When I started working with him fifteen years later,” Herzog writes, “I knew what I was letting myself in for.” In fact, it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that it was not despite Kinski’s sheer awfulness but at least partly because of it that Herzog pursued him as a collaborator. He can’t have known at the time quite how depraved and wicked the man really was. And yet it’s difficult now to watch Aguirre, with its queasy undertow of incest between the conquistador and his young daughter, without thinking of Pola Kinski’s disclosure that her father repeatedly raped her throughout her childhood.

In the memoir Herzog notes that 20th Century Fox wanted to make Fitzcarraldo and that Jack Nicholson, who admired his work, was intent on playing the title role. It soon became clear, though, that Nicholson and Fox wanted the whole thing to be shot at a botanical garden in San Diego, with a plastic scale model for the ship. (Nicholson, Herzog points out, “only took parts that left him free to watch Los Angeles Lakers’ games.”) There is some bathos to the idea of this alternative Fitzcarraldo—its Hollywood star with one eye on the ball game, its plastic ship, its domesticated little jungle—but I didn’t quite buy Herzog’s implication that it would necessarily have been a lesser work of art. I thought immediately of Stanley Kubrick, who shot one of the greatest war films ever made, Full Metal Jacket, not in the rainforests of South Vietnam but in a series of locations that were all within a couple of hours’ drive of his house in Hertfordshire. Kubrick was a lesser personality than Herzog, a lesser character, but also a greater filmmaker.

And this brings us, by an arduous crossing of dense terrain, to the heart of the matter: we can argue all day over whether Herzog’s best film is, say, Aguirre or Grizzly Man—both extraordinary achievements of very different sorts—but there is no doubt that his real masterpiece is the character known as Werner Herzog. This is not to diminish the scale of his cinematic achievement, to paint it as somehow the work of a shallow self-promoter, but rather to insist that the power of his work is often inseparable from, and in fact reliant upon, this persona. This is why I suspect that when you think of Werner Herzog you don’t think of any one film or any one scene, however indelible some of those might be. What you think of is the sound of Herzog’s incantatory voice—which, in Michael Hofmann’s translation, is present on every page of the memoir.

But you don’t just think of the voice because of its sound, you think of it because of the incredibly intense and poetic things it is so often saying. It seems both strange and entirely appropriate, in this sense, that arguably the most famous moment of Herzog’s entire career—the moment I myself, as a devotee of long standing, immediately remember when I think about how great Werner Herzog is—occurs in a film he did not himself direct. It’s the scene toward the end of Burden of Dreams in which Herzog, addressing Les Blank’s camera head-on, delivers an extraordinary monologue about the pitiless, teeming absurdity of the jungle that surrounds him:

Taking a close look at what’s around us, there is some sort of harmony. It is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder. And we in comparison to the articulate vileness and baseness and obscenity of all this jungle, we in comparison to that enormous articulation, we only sound and look like badly pronounced and half-finished sentences out of a stupid suburban novel, a cheap novel. And we have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication, overwhelming growth, and overwhelming lack of order. Even the stars up here in the sky look like a mess. There is no harmony in the universe. We have to get acquainted to this idea that there is no real harmony as we have conceived it. But when I say this, I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it. I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgment.

This is, obviously, amazing. It’s amazing even when pressed and flattened into text, and it’s even more amazing to see Herzog just come out with it while standing there in the middle of the jungle. When he later reused the scene in his own documentary, My Best Fiend, its context, in a film about his tumultuous relationship with a horrible man to whom he was nonetheless inexorably drawn, lends it a different emphasis. He’s still very much talking about the jungle, but he’s also talking about Kinski, whose ghastly charisma he loves against his better judgment. His resistance to self-analysis leads him to refer to the central motif of Fitzcarraldo as a “wonderful metaphor” of whose meaning he has no notion. But I’m tempted to suggest that pulling a steamship over a hill is a pretty good metaphor for working with Klaus Kinski, which is to say that Fitzcarraldo is an elaborate allegory for the process of its own creation.

There’s a wonderful scene, toward the end of My Best Fiend, in which Herzog is speaking with the Swiss photographer Beat Presser, whose stills documented a number of Herzog’s projects, including Fitzcarraldo and Cobra Verde (1987), the last of the films he made with Kinski. Looking at one of Presser’s framed Fitzcarraldo photos, of the steamship on the hill, Herzog makes a version of the same ship-as-metaphor point: “It’s a great metaphor. For what, I don’t know to this day. But it’s a great metaphor.”

A moment later, they are standing before a photo from the Cobra Verde shoot, of Herzog demonstrating the manner in which Kinski should walk, and Presser says: “You used to act things out for Klaus, beautifully. You would have also been a good Fitzcarraldo. That’s what you are, in reality.” Herzog doesn’t quite ignore the remark; he acknowledges it with a polite laugh. But before Presser can say any more on the matter, Herzog has moved on, as though there is nothing further to be said. The steamship is to be left where it lies, unmolested, in the personal depths.