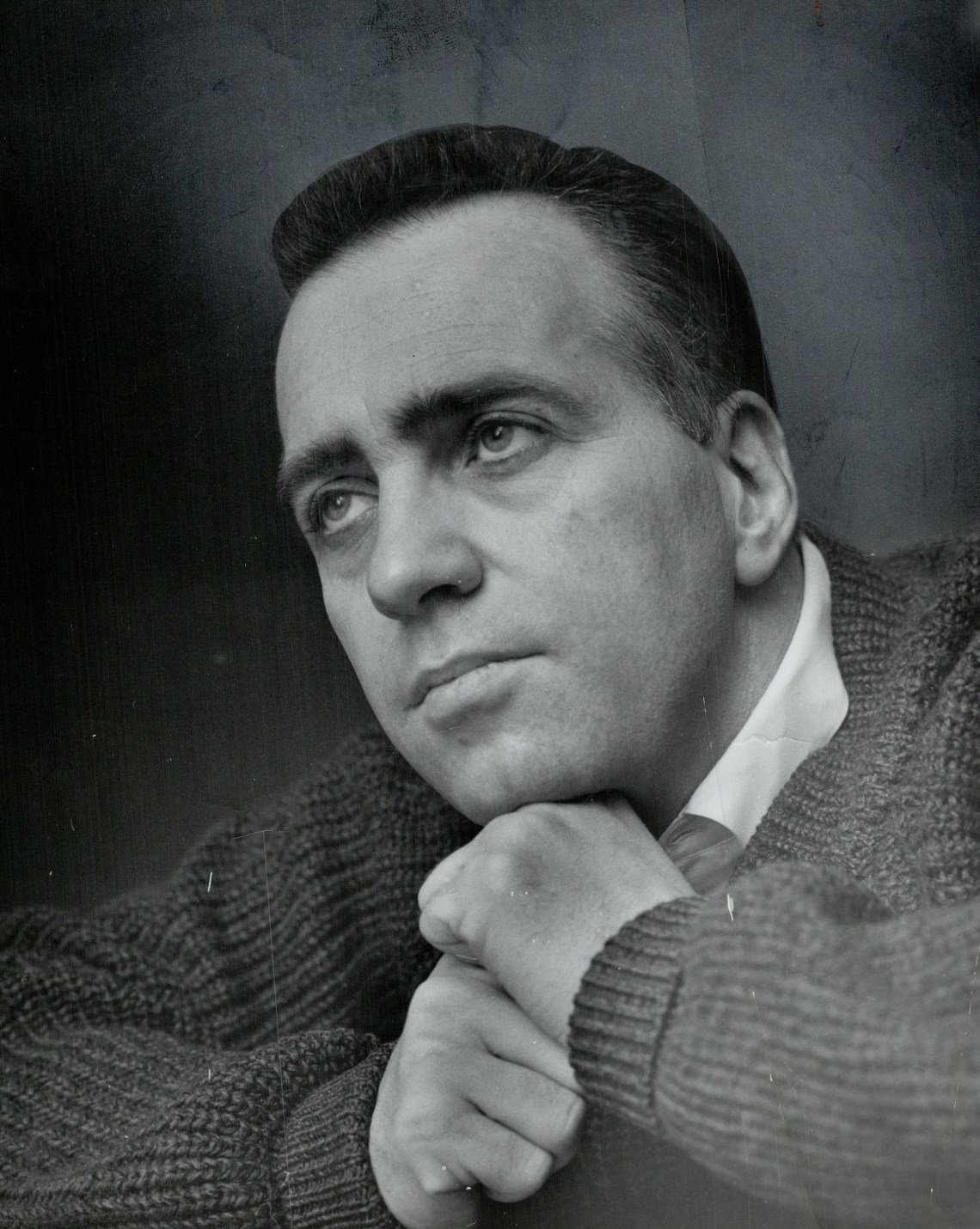

Jean Shepherd is today best-known for A Christmas Story, the 1983 movie based on his 1966 book In God We Trust: All Others Pay Cash. He worked primarily as a radio personality from the mid-1940s into the 1970s, establishing himself during that brief period of American history when someone could make a living as a “raconteur.” He also tried his hand at writing a few short-lived TV shows and a handful of screenplays, narrating jazz albums, and compiling semifictionalized accounts of his youth and domestic life into short story collections with names like Wanda Hickey’s Night of Golden Memories: And Other Disasters. But it’s A Christmas Story that remains unbearably, stupefyingly popular long after his death. People often complain about the ubiquity of It’s a Wonderful Life reruns, but it hasn’t been screened half as relentlessly as A Christmas Story, which has aired in a twenty-four-hour Christmas loop on TNT for more than twenty-five years and on TBS for nearly two decades, to say nothing of the repeated one-off showings between Thanksgiving and Christmas.

None of his other work approaches anywhere near that level of success: not his 1975 album Jean Shepherd Reads Poems of Robert Service; not his voice work for Walt Disney World’s Carousel of Progress (he’s responsible for all of the nonsinging lines from John, the optimistic animatronic paterfamilias); not his parody pulp novel, a collaboration with Theodore Sturgeon called I, Libertine (the pull-quote on the cover reads, “‘Gadzooks!’ quoth I, ‘but here’s a saucy bawd!’”); and not his other collections of semifictionalized reminiscences, such as The Ferrari in the Bedroom (1972).

Yet his (often unattributed) influence saturates the cultural landscape to a surprising degree. Shepherd’s relationship to “the system” was a slightly tortured one, in a fashion common to his generation: he went to college on the G.I. Bill, made a living on late-night radio reading poetry and delivering off-the-cuff diatribes against conformity, accidentally stumbled onto a short-lived television show, and was allegedly once considered as a replacement for Steve Allen on the Tonight Show. These gigs were often canceled, sometimes because of his contentious relationship to advertisers, but just as often reinstated; the system was often fairly good to him, but never as good as he thought it ought to have been, and he prided himself on biting the hands that tried to feed him.

From 1955 to 1977, with a short break in 1956 when he was fired and quickly reinstated after a listener write-in campaign, Shepherd hosted a show on WOR AM radio in New York City in which he staged hoaxes, instructed listeners not to vote, and pretended to lock himself out of the office. In a regular segment called “Hurling Invectives,” he would order listeners to “put your radio on the windowsill…the loudspeaker pointed out towards the neighborhood…. This voice will carry your sentiments, your repressions, your aggressions, into the darkness out there.” Then he would shout accusations like “You don’t think for a moment you’re fooling anyone, do you?!” or “You filthy pragmatist!”

This routine later appeared in A Thousand Clowns, Herb Gardner’s 1965 film, adapted from his own play, about a male Auntie Mame fighting to keep custody of his nephew without knuckling under to midcentury conformity. The lead, Murray, played by Jason Robards, periodically leans out of his window to shout things like, “Neighbors, I have never seen such a collection of dirty windows!” and “By next week I want to see a better class of garbage, more empty champagne bottles and caviar cans!” But the segment’s best-known successor is probably in Network, where Peter Finch’s deranged Howard Beale instructs his television audience: “I want you to get up right now and go to the window, open it, and stick your head out, and yell: ‘I’m mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take this anymore!’”

By Shepherd’s account, Clint Eastwood’s disc-jockey character in Play Misty For Me was also based on him, although his biographer Eugene B. Bergmann reports that he thought the same about Shel Silverstein’s “A Boy Named Sue,” and we might do well to take such claims with a grain of salt.1 We are on firmer ground with Zippy the Pinhead, the underground comic character whose creator Bill Griffith spoke repeatedly on record about Shepherd’s influence, and Charles Mingus, who recruited Shepherd to improvise the monologue in the title track of his record The Clown (1957). In 2015 Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen extolled “Shep” as “one of a handful of adults you could trust” back in the 1950s; Shepherd’s on-air reading of a newspaper clip Fagen mailed him, he remembered, meant that “my life as an independent consciousness had begun.” It’s a delightful essay, but I must disagree with Fagen’s assessment of A Christmas Story:

Advertisement

While the film preserves much of the flavor of Shep’s humor, not much remains of the acid edge that characterized his on-air performances. In the film, the general effect is one of bittersweet nostalgia; on the radio, the true horror of helpless childhood came through.

Yet I think the primary reason A Christmas Story has become so ubiquitous is precisely because of its commitment to cataloging every single injustice, public humiliation, and petty injury of childhood. I’ve never watched it and felt anything like nostalgia, despite having grown up in the Midwest only a few decades after Shepherd; I always come away from A Christmas Story feeling ritually cleansed, or as if I’ve narrowly escaped a particularly nasty end. It’s an uncomfortable movie, a small-scale Passion of the Christ, about Ralphie, a small boy whose sole wish in life is to end the adult monopoly on violence by getting a gun, which he is repeatedly assured will result in him “shooting [his] eye out.” It ends with the arrival of the gun, which leads him to ricochet a shot into his face and step on his own glasses, technically fulfilling the prophecy of sightlessness, and the adult Ralphie-as-narrator (voiced by Shepherd) recalls that it was “the greatest Christmas gift I had ever received or would ever receive.”

Ralphie has exchanged sight for violence, successfully lied to his mother, and gotten his heart’s own desire, which has made him just as happy as he always knew it would. The gleeful satisfaction of the ending is consonant with both horror and comedy, which is unusual in both children’s media and Christmas classics, two profoundly moralizing genres. Not many other Christmas movies end with the triumph of materiality, affirming the power of fulfilled desire to truly satisfy. The twin messages of that final scene are “I got what I wanted, and it worked” and the even more countercultural “Violence pays off, kids”; it’s the triumph of a tiny Scrooge, replayed again and again for a full day and night every year.

*

Outside A Christmas Story, Shepherd is a well-known influence on Garrison Keillor and Jerry Seinfeld, among others. In fact, in a 2012 Paley Center interview Seinfeld attributed Seinfeld’s “dramatizing of the ordinary” in part to Jean Shepherd’s radio show, where “you can see that he had a similar gift.” As is usually the case with “the writer’s writer” and “the comedian’s comedian,” those he influenced often went on to be far more popular and successful than he ever was himself, a trend he noticed and disliked intensely. But he hardly lacked for professional opportunity. He resented Herb Gardner for mining elements of his routine for A Thousand Clowns; Bergmann quotes Shepherd saying the play had “stolen my life.” But nothing was keeping Shepherd from writing something like A Thousand Clowns himself, if he’d wanted to.

The thematic justification for a “show about nothing” is already present in those old WOR shows, as from this midcentury episode:

Now all of this might seem to you to be a mélange of nothingness—but isn’t really a mélange of nothingness. Not at all. Because it is a mélange of our life, the existence we live. And if you’re going to be fulfilled, you’ve got to live your existence out. You’ve got to play out the string.

Many of the most characteristic elements of Seinfeld were already fully realized in Shepherd’s work: an obsession with minute details, comically angry and ineffective fathers, grand enthusiasm for things like the perfect shirt; petty joys and petty problems. This is of course not to say that Seinfeld or later works inspired by Shepherd lifted anything from him, just that he excavated the hallmarks of the genre early, distinguishing “being about nothing” from its parent category of “light domestic fiction,” à la Jack Douglas and Erma Bombeck.

Shepherd also managed to neatly dodge the problems of accuracy that sometimes trouble memoirists, especially “humorous memoirists,” whose work depends on a certain degree of implied exaggeration that can prove ruinous beyond certain limits: Augusten Burroughs’s Running With Scissors (2002) was reissued with an “Author’s Note” after Burroughs and his publisher settled a lawsuit brought by the family who helped raise him. The note is not quite an apology, nor precisely a defense of the book-as-written:

I recognize that their memories of the events described in this book are different than my own. They are each fine, decent, and hard-working people. The book was not intended to hurt the family. Both my publisher and I regret any unintentional harm resulting from the publishing and marketing of Running with Scissors.

In 2007 The New Republic published an article that fact-checked David Sedaris’s 1997 nonfiction essay collection Naked; in 2012 This American Life officially retracted the episode “Mr. Daisey and the Apple Factory” after producers learned that the performer Mike Daisey had invented details about Foxconn factories. It can be a difficult line to walk; humorists are not expected to work from scrupulously exact photographic memory, and to some extent exaggeration is expected, is even part of the genre’s allure, but lawsuits and hostility inevitably follow those who cross the invisible line between inventiveness and deceit.

Advertisement

Shepherd sidestepped such snares entirely. I, Libertine, which was also his first novel (actually written by Theodore Sturgeon, based on a radio concept and subsequent outline of Shepherd’s), began as a joke, thus getting the problem of hoaxes out of the way early in the game. Suspicious of the criteria for inclusion on The New York Times best-seller list, Shepherd told his readers to ask booksellers for a waggish Regency novel called I, Libertine by “Frederick R. Ewing” in order to flood the market with demand; this had the intended effect and then some, and was later spun into a real book deal. In God We Trust and other essay collections were all marketed explicitly as fiction, although always fiction on nodding acquaintance with reality. Shepherd’s primary concern lay with the plausible, the unimportant, the trivial, and the mundane, never with the exact. A Fistful of Fig Newtons (1981) opens with a cautionary note:

This book is a work of the imagination. However, some essays are observation and conclusion. The characters depicted in the short stories are fictional. They do not represent any actual individuals, living or dead.

Most of Shepherd’s career, particularly his first three decades on the radio, relied on riffing and improvisation, which makes for a vast but fairly evanescent archive. People often rewatch classic movies, and sometimes rewatch beloved old TV shows, but they very rarely replay old radio shows. The real marker of twentieth-century success always lay in syndication, and it’s there, a little late in the game, and in a medium that had otherwise eluded him, that Shepherd secured his legacy. In the petty grievances and joys of Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm, in NPR-style storytelling, in everything that straddles the line between countercultural and popular representative of the monoculture, from Calvin and Hobbes to Steely Dan, echoes of his work can be found, so abundant and diffuse they can be easy to miss—but they’re everywhere you care to look.