Christopher Wheeldon’s most recent full-length ballet opens with a romantic and morbid image. When the curtain rises, thirteen women in white gowns appear standing in a horizontal line. Each bride holds a red rose and wears a mask—a white skull, suggesting the Calaveras Catrinas that appear on the Day of the Dead in Mexico, where the ballet is predominantly set. Slowly, the brides back away. As they turn to face upstage, we realize they’d had their backs to us all along. For the first time we see their stoic faces and the front halves of their costumes: black mourning robes. They sit down on a row of chairs far upstage and start knitting.

You can sometimes forget these women as you’re absorbed by the winding drama of Like Water for Chocolate, Wheeldon’s first evening-length ballet in six years. But they’re there knitting for most of the first act. Their rigged chairs eventually levitate, showing what they’ve been making: a huge crocheted blanket. By the end of Act I the women have flown up and out of sight, but the blanket stays behind, transformed into a vast backdrop.

The ballet’s heroine, Tita, suffers a breakdown right after these women disappear. Her beloved baby nephew has died, and Tita blames her mother, Mama Elena. The two fight: Mama Elena grabs Tita by the neck, pulls her onto the floor, and viciously slams the ground around her daughter. Stricken, Tita is left alone in a crumpled heap. When their family physician Doctor John arrives to help, he tenderly points Tita’s flexed foot and rests his head on top of hers. As he lifts her up, her body drops in his arms like a dead weight. Having got her on her feet, the doctor picks the edge of the blanket up off the floor and gingerly wraps it around Tita’s shoulders. Huddled together, they walk toward the audience. Tita—hunched and shaken, eyes searching the horizon—looks broken but divine as her crocheted cloak ascends to the heavens.

It’s a brilliant coup de théâtre. Readers of Wheeldon’s source material, the 1989 novel by Laura Esquivel, will know that the backdrop represents the bedspread Tita knits over years of sleepless nights after Mama Elena forbids her from marrying her true love, Pedro. Over the course of the book the bedspread grows so large it covers Mama Elena’s ranch. By giving the blanket multiple creators—both brides and mourners, with skull masks and human faces—Wheeldon presents Tita’s experience as collective and enduring. The backdrop draws together women who have felt the joys and agonies of loving and losing someone—an image of shared emotions that subsumes the particular details of Tita’s struggle.

“Laura’s story is so universal in its themes of desire, of repression, and ultimately, of liberation,” Wheeldon tells the critic Judith Mackrell in the program for the ballet’s world premiere in London. He has often spoken in interviews about wanting to make work driven by shared emotions and “universal” in its appeal. Discussing his Tony Award–winning choreography for a 2022 Broadway production about Michael Jackson, MJ: The Musical, he called the show “an exploration of the man who made this universal music that connects all of us.” This commitment to making art that affects and entertains broad audiences has drawn Wheeldon to well-known stories and subjects, and led him to set his polished choreography in visually arresting onstage worlds. It can also result in evading complexities in his source materials that would require reckoning further with their historical setting and politics.

For the past three decades, Wheeldon has been among the most sought-after choreographers in the world. Having first come to fame with plotless, abstract ballets, he’s since turned to multi-act literary adaptations, an interest further fed by his recent successes directing and choreographing for Broadway. This year audiences can sample many phases of his career. Commemorating its seventy-fifth anniversary, New York City Ballet is honoring Wheeldon’s contributions to the company with several shows in its winter 2024 season; MJ: The Musical opens in London in March; Like Water for Chocolate returns to the Metropolitan Opera House in July. And in September, the Australian Ballet will premiere Oscar, his next large-scale work, based on the writings and life of Oscar Wilde.

*

Wheeldon was born in Somerset, England, in 1973. After starting out at a local dance school in a village hall, learning to tendu and plié while gripping the back of a chair, he was accepted to the elite Royal Ballet School, where at age eleven he took an energetic stab at choreography. His first ballet, The Syncopated Clock (1984), was set to plucky orchestral music by Leroy Anderson: a girl starred as a domineering clock that ordered a businessman, road builder, and bus driver to eat and work.1 As he progressed through the school, Wheeldon choreographed nonnarrative works that won him awards. He joined the Royal Ballet in 1991; soon, his creations caught the eye of Kenneth MacMillan, the company’s former director, who praised and encouraged him.

Advertisement

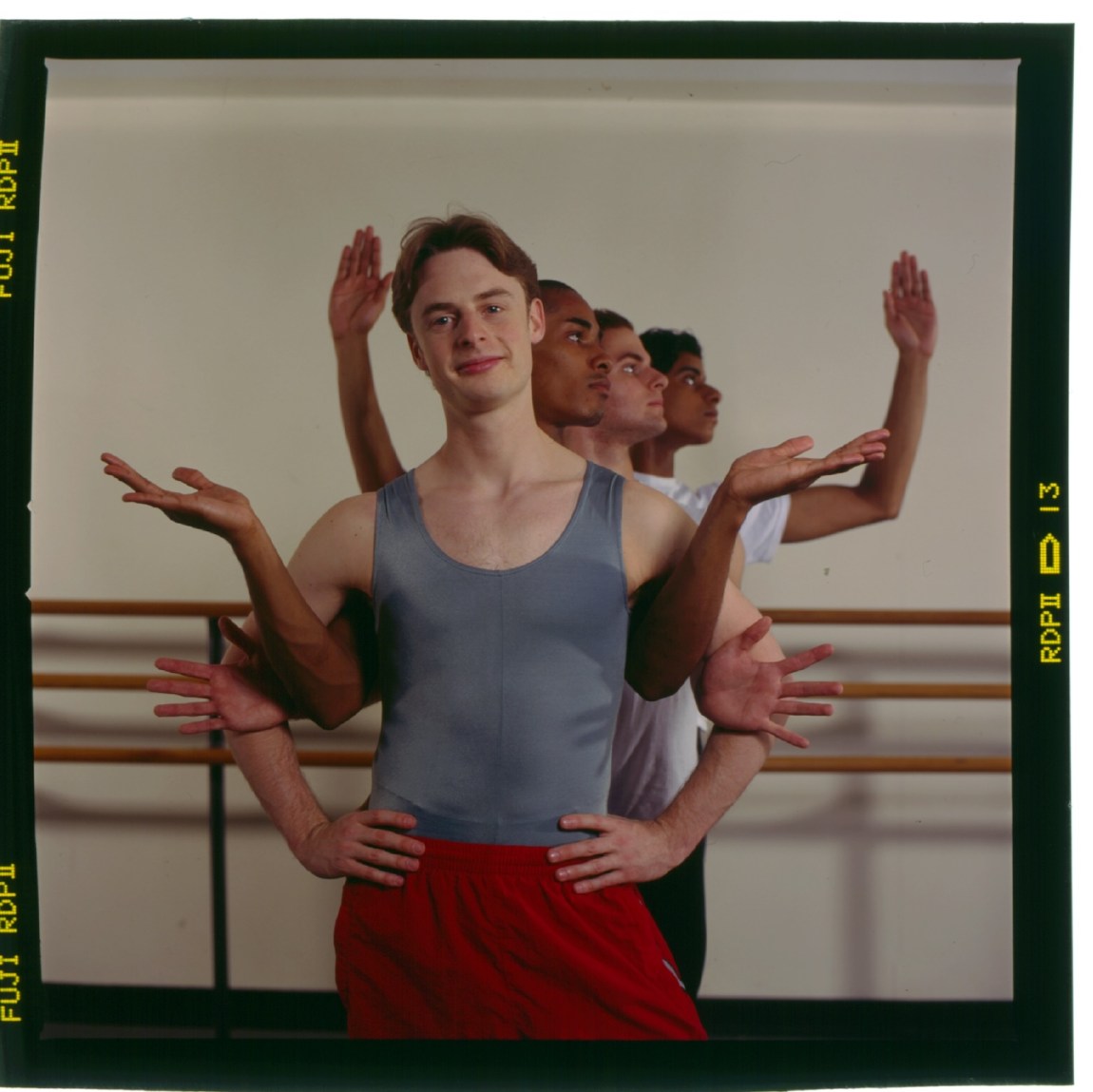

By 1993 Wheeldon was dancing for New York City Ballet. He’d come to Manhattan for a holiday, not an audition, but after he took NYCB’s company class on a whim they offered him a contract. By the end of the decade, Wheeldon was creating ballets for NYCB that inventively melded his unmannered, lyrical British training with Balanchinian neoclassicism. In 2000 he quit dancing to focus exclusively on choreography. The next year, he made Polyphonia for the company. Set to an avant-garde score by György Ligeti, this one-act ballet was spare and modern: it had no sets or backdrops, and the dancers wore sleek purple leotards. The movement was both smooth and angular, with an acrobatic, preternatural, and elegant central pas de deux for the principal dancers, Wendy Whelan and Jock Soto. (Polyphonia returns to the company’s stage for five performances this season.) Critics called him a wunderkind, a possible successor to Balanchine.

As his star rose in the ballet world, Wheeldon ventured into new territory. In 2002 he choreographed a Broadway production of the musical The Sweet Smell of Success, which flopped. After retreating back to his ballet commissions, in 2007 he took another risk and, with the former NYCB principal dancer Lourdes Lopez, cofounded Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company, a transatlantic troupe dedicated to collaborations between choreographers, composers, and visual artists: Diaghilevian Gesamtkunstwerks for the twenty-first century. The dream was short-lived; Wheeldon left the company in 2010. His work had received mixed reviews, and by some accounts the group struggled financially during and after the recession. But the spirit of artistic unity has motivated his subsequent large-scale projects, which depart from the starker look of many of his earlier works.

Like Water for Chocolate is Wheeldon’s latest venture in a genre attracting choreographers today: ballets based on literary sources. It follows his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (2011) and The Winter’s Tale (2014), both premiered by the Royal Ballet. With choreography rooted in classical dancing, each features a commissioned score and designs that are contemporary and lavish. Alice, for instance, includes a giant Cheshire Cat puppet: aided by projections, the cat dismembers and re-assembles as it slinks across the stage. By choosing familiar titles, Wheeldon has tried to attract an array of audiences, including viewers who might be seeing a ballet for the first time. Such ambitions have led some critics to call him a “populist”—a perhaps imprecise way of characterizing his quest to widen ballet’s appeal. After the success of Alice, Wheeldon returned to Broadway. He went on to choreograph and direct An American in Paris, which won four Tonys, and, in collaboration with the playwright Lynn Nottage, MJ: The Musical.

Others have compared Wheeldon to the director-choreographer Jerome Robbins, with whom he worked at NYCB, not least because they both bridge ballet and Broadway: Robbins’s West Side Story (1957) made dance essential to the dramatic action of musical theater. But while Wheeldon has taken inspiration from Robbins and other luminaries of American popular theater and music (some of his NYCB works were set to Gershwin and Rodgers and Hammerstein), he has also described himself as a child of the Andrew Lloyd Webber generation: a lover of epic, melodramatic box-office hits like Cats (1981) and The Phantom of the Opera (1986). And by returning to narrative, he has followed Kenneth MacMillan, perhaps best known for the full-length story ballets he created for the Royal Ballet, including Romeo and Juliet (1965). Like Water for Chocolate builds on these influences; it also directs Wheeldon to a setting that’s new to him.

*

The story moves through the early twentieth century, between northern Mexico and Texas. Tita de la Garza lives under a curse: per family tradition, as the youngest daughter she must take care of her mother, vowing not to marry until the older woman dies. As a teenager she falls passionately in love with Pedro, but Mama Elena forces him to marry Tita’s sister Rosaura. Tita spends the rest of the story struggling to reunite with her true love. Food is central to the book: its title both refers to a tradition of using water to make hot chocolate and suggests emotions coming to a boil. A gifted cook, Tita uses meals to channel her feelings and exert power. Forced to bake a wedding cake for Pedro and Rosaura, she lets her tears flow into the batter; later, at the wedding, the guests vomit after eating it, overcome by sadness and loss. The novel traverses a range of genres and tones—punctuated by recipes, its narrative recalls romance serials and, as the scholar María Elena de Valdés points out, historic Mexican women’s magazines.2

Advertisement

Coproduced by the Royal Ballet and American Ballet Theatre (ABT), Like Water for Chocolate premiered in London in June 2022; ABT brought it to New York City last summer. Wheeldon consulted with Esquivel throughout the creative process—a notable level of involvement by an author for a literary ballet. He worked closely with the British composer Joby Talbot to condense the story into a scenario, concentrating on the novel’s central characters—Tita, Pedro, Mama Elena, Doctor John, the family’s elderly cook Nacha, and Tita’s two sisters—and situating them in what Wheeldon called an “abstract poetic landscape.”

In music, design, and movement, the creative team played down the story’s Mexican setting while retaining some of its inflections. Composing the score, Talbot took advice from two celebrated Mexican artists, the conductor Alondra de la Parra and the musician Tomás Barreiro; his cinematic orchestration includes instruments such as the ocarina, teponaztli, and marimba. The Irish designer Bob Crowley referred to archival images gathered by de la Parra and her sister, Camila. He took a cue from the Mexican architect Luis Barragán’s minimalist aesthetic: scenes at the de la Garza family ranch feature mobile earth-tone slats that invoke flattened beams. Wheeldon stuck with a classical movement vocabulary: he researched Mexican folk dances, but didn’t try to recreate them, instead scattering evocative emphases—a particular use of weight or rhythm—across the choreography.

Critical moments in the ballet play out as pas de deux. When she’s dancing alone in Act I, during Pedro and Rosaura’s wedding, Tita’s otherwise luscious movement becomes jerky, roiling, contorted. At one moment, she crosses her long braids in front of her neck and mimes choking herself. When Pedro is onstage with Tita but separated from her, he expresses his frustrated yearning in grasping gestures and undulating motions. Cassandra Trenary and Herman Cornejo—exemplary technicians—brought sensitivity and subtlety to their characters.

When Tita and Pedro are together, Wheeldon’s choreography signals both the passage of time and the evolution of their love. In their first duet they are young and buoyant, playfully circling a table, jumping, rolling, and diving through the space, before sharing a light kiss. After Pedro marries Rosaura, their meetings grow more erotically charged. One evening they run into each other outdoors, between clotheslines draped with white sheets. At the start of this duet Pedro hovers his hand close to Tita’s body: without touching her, he slowly traces it around her frame, his arm strained with tension. When they finally make contact, relief and release wash through their bodies: they sway and flow through a partnering sequence that becomes more acrobatic and thrusting. The movement expresses a magnetism that we don’t see in Pedro’s rigid duets with Rosaura, whom he can barely look at, or in Tita’s duets with Doctor John, who is briefly her fiancé. Her partnering sequences with the doctor, danced by Thomas Forster, are soft and serene, with gentle lifts and falls: it’s love of a different kind.

*

The pacing throughout Like Water for Chocolate is fast; the fluid choreography gives a sense of constant motion. (The speed can be disorienting. Viewers unfamiliar with the novel might wonder, for instance, why ghosts float on and off the stage.) The elaborate production design also propels the story forward. In the first scene, a bundled cream blanket symbolizes Tita as a newborn baby. Unfurled and spread over a table, it transforms into cooking dough for the young Tita, now played by Trenary. In one of the book’s most memorable moments, Tita sprinkles petals from a rose Pedro gave her into a quail dish for her family. The meal infuses her second sister, Gertrudis, with Tita’s lust, sending “an intense heat pulsing through her limbs.” Soon she strips off her clothes and galavants off on a horse with a revolutionary fighter.

In the ballet, after Gertrudis—danced by the fearless Catherine Hurlin—takes her first bite, rose petals fall from the sky and men in red and pink costumes emerge to serenade her. We’re catapulted into a fantasy world where Gertrudis dances with power, crispness, and abandon, arching her back, kicking her legs, twisting, swooping on top of the table and into the arms of the men, who hoist her into the air and circle her hungrily as she climbs over and commands them. She rips off her high-necked, long-skirted dress to reveal a glittery, nude-colored leotard and mounts a rocking mechanical horse as she makes her escape from the family ranch. The scene is as provocative and flashy as a musical number, even as Crowley’s streamlined designs and Hurlin’s show-stealing performance keep it from becoming overwrought.

The ballet’s subsequent treatment of Gertrudis, however, suggests how Wheeldon’s “poetic abstraction” and emphasis on legible emotions can also flatten the novel’s political and historical specificity. Esquivel’s story is set during the Mexican Revolution; in the book, Gertrudis goes on to become the leader of a revolutionary battalion. But when she reappears in Act II of the ballet with a large crew, the choreography suggests romping bohemians, not necessarily rebel troops. Wheeldon and Tablot also excise an episode from the novel in which bandits pillage the ranch, leaving Mama Elena partially paralyzed. Though period-inspired costumes and video projections indicate where we are (“Mexico, 1910”; “Twenty Years Later”), the setting’s violence and national reckoning are passed over.

Like Water for Chocolate can also fall back on Talbot’s dramatic leitmotifs and Crowley’s richly colored designs to express character and mood. Stripped of these layers, the choreography would lose some force. After Mama Elena’s funeral in Act II, Tita discovers an old, secret box containing a dried rose and love letters addressed to her mother. A dream sequence follows that depicts Mama Elena’s own story of thwarted love. We learn little from the movement about her lover, or about the crowd of masked people determined to end this romance. The most clarifying moment comes when a woman from the crowd uses a ribbon to fasten Mama Elena, danced by Christine Shevchenko, to another man—repeating an action Mama Elena herself performs in Act I, binding Pedro to Rosaura. Without the prop, we might not fully grasp this story and its sad legacy.

Elsewhere choreography and production elements combine to great effect. After decades of separation, a much older Tita and Pedro finally reunite in the ballet’s closing pas de deux, a not-so-subtle consummation. Here Wheeldon balances passion with classical grace. Alone onstage, Tita wears a skin-colored leotard with a thin, sheer skirt, and Pedro wears flesh-colored tights. Placing their hands on each other’s chests and taking deep, exaggerated breaths, they repeat a heartbeat motif that has recurred throughout the ballet. Pedro carries Tita carefully through the air; there are clean arabesques and stirring drops, culminating with a moment in which she fastens her ankles around his neck and hangs upside down, their bodies stretched and fused. The dancing is accompanied by a rendition of a passage from Octavio Paz’s poem “Piedra de sol” (1957) by the soprano Maria Brea:3

Los dos se desnudaron y se amaron

por defender nuestra porción eterna,

nuestra ración de tiempo y paraíso,

tocar nuestra raíz y recobrarnos,

recobrar nuestra herencia arrebatada

por ladrones de vida hace mil siglos…

Finally Tita and Pedro climb into a bed, the last prop to appear onstage. A piece of stage equipment hoists them into the air. Folded into an eternal, glowing embrace, they’re engulfed by video projections of flames, watched over by the thirteen brides.