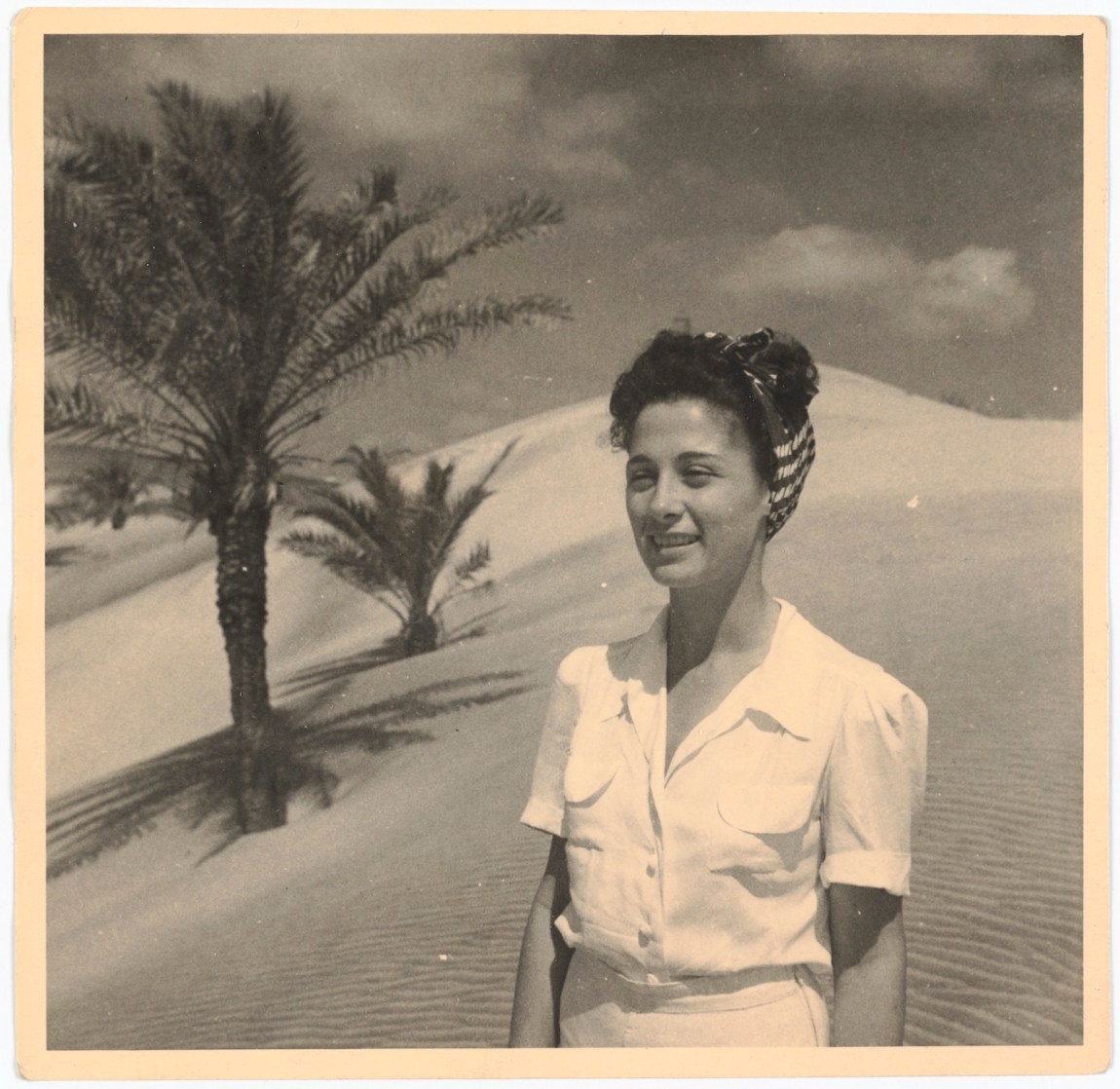

One morning in 1952 Gaby Aghion, an haute-bourgeois Egyptian Jewish émigré to Paris, woke up with a feeling of emptiness. “It’s not enough to eat lunch,” she told her husband, Raymond. The Aghions were hardly just fixtures at the Café de Flore. Back in Egypt, Raymond had purchased Al Majalla Al Jadida (The New Magazine) to provide a forum for the country’s ascendant left, and during the war he had established an organization to support the French Resistance. In Paris, where they moved in 1945 to attend the École des Sciences Politiques, the couple joined the Communist Party and lived among intellectuals and artists (Paul Éluard, Picasso), many of whom were Jewish and had been uprooted from around the world.

Aghion’s husband suggested she do something with fashion to fill her time, since other women had always complimented her clothing. Hillel Schwartz, the founder of the Egyptian Communist organization Iskra, recalled that at a political meeting in Cairo convened by Raymond’s cousin Henri Curiel, Aghion had been

outrageously made up, with very short dresses. She would sit with legs crossed, the skirt up high, and she would begin to do her nails. From time to time, she would come late…and excuse herself by saying that it was because of her hairstylist or seamstress. And we were there to study Marxism! When I would lecture Gaby, she would respond: “Marxism is not discomfort.”

In Aghion’s Paris there were many intellectual women who surely agreed. As “Mood of the Moment: Gaby Aghion and the House of Chloé,” an exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York, makes clear, Aghion socialized mainly with artists and writers, many of them Party members, who could afford couture but had neither the time nor the desire to attend fittings for every dress they needed made. At the time, Aghion said, “in France there was either couture or confection”—off-the-rack, low-quality imitations of couture with sloppy details added “here and there.” Women could either have one-of-a-kind dresses made by houses like Dior or buy shoddy confections made from inferior fabrics. “Well-crafted ready-made garments, with beautiful materials and beautiful handwork, did not exist,” Aghion said. So she decided to put together “a little collection of charming dresses, in very pretty colors, which women will fancy.” What seems like a breezy whim was actually quite bold. When Aghion arrived in Paris she found a society less egalitarian than the Cairene circles she had moved in—women could not open a bank account, let alone a business.

Aghion didn’t know how to sew, so she hired seamstresses from the French couturier Lucien Lelong, who as wartime president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture had thwarted the Nazis’ plan to move Paris’s ateliers to Berlin. She borrowed the name for her brand, Chloé, from a friend because she liked “the roundness of its letters,” and because her own name sounded like a “fortune teller’s.” She sold her first dresses to the boutiques that she herself frequented. To describe her new style, Aghion coined the term prêt-à-porter—ready-to-wear. (Until now the term has most often been credited to Yves Saint Laurent, who didn’t use it for another fourteen years.)

In the early days of Chloé, Aghion designed everything herself. Soon she hired her friend Jacques Lenoir, a Jew who had fought for the Resistance, to help with the business side. With a team of freelance designers they created and sold a twice-yearly collection of ready-to-wear. Theirs was not a traditional atelier, in which a designer reigns over seamstresses who realize their vision: Aghion called her setup “a Marx Brothers room” where “the designers would sort of kill each other every season.” Rather than elaborate couture dresses, they made wool skirt-suits, diaphanous blouses, and flouncy party dresses to wear with floral hairpins and miniature renditions of men’s bowler hats: clothing for emancipated left-bank women with jobs and lives who didn’t have time for frippery, at least not every day.

Such women no longer had to choose between feeling frivolous and looking drab. The early Chloé designs—represented at the Jewish Museum in photographs, as the clothes no longer survive—are adaptable, somewhat rugged, looser dresses and suits, without the intricate craftsmanship and precise body-hugging tailoring of couture. Aghion first showed them in the late Fifties at Brasserie Lipp, Closerie des Lilas, and Café de Flore, the favored haunt of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. This was a pointed gesture. Couture houses were stuffy, exclusive institutions, accessible only to the wealthy clients who secured invitations to their shows. “It is common practice to ask customers who come in ‘off the street’—minus letters, credentials, fashion background—what hotel they are staying in,” Sally Iselin wrote in her 1951 Atlantic report “I Bought a Dress in Paris.”

Advertisement

If it is not the Ritz or the George V, the head rendeuse visibly loses interest, but she is sophisticated enough to realize that there are three or four other hotels on the Right Bank which are favorites with rich Americans. Anyone who stays at the top ten or twelve will get an invitation to a showing if she is in Paris long enough for the concierge to get her name in the Paris Herald. The rich eccentric who stays in a hotel on the Left Bank has little chance.

It was a marked departure from this convention to have a show at a left-bank brasserie. Still, though the ideal Chloé consumer was left-wing, she was hardly a member of the proletariat; she was something like Anne Dubreuilh, the heroine of Beauvoir’s The Mandarins, a psychoanalyst who detests fashionable Paris but takes pride in the way she dresses and delights in buying outfits to attract her American lover. In the novel, quirky and simple clothes are armor for tense social situations, including affairs and confrontations with men. Dubreuilh despises the novel’s grand villainess, a couturier and society doyenne; anyone who wears couture is evil and brainless.

*

Most fashion exhibitions are monuments to creative genius. Aghion demands a different treatment. “I have no talent,” she once said. “I recognize the talent in others.” “Mood of the Moment” displays the work of the ten designers who have helped steward the brand since the 1960s, including Karl Lagerfeld, who in 2023 was given a retrospective of his own at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, where his famous line “Fashion does not belong in a museum” was painted above the doorway.

Lagerfeld came to Chloé in 1963, a step down from high couture to the commercial realm of ready-to-wear. At Chloé he joined a group of designers, many of whom, like the former Elsa Schiaparelli model Maxime de la Falaise, had excellent taste but no formal training. His designs were the first to dominate the collections: his great talent was for rendering sophisticated silhouettes in light fabrications that were easy to produce and fit many body shapes. Eventually he became the label’s sole designer, having, according to Aghion, “chased them all away.”

Aghion, who had no interest in being a public figure, promoted Lagerfeld to sole designer in 1974. Having ceased designing herself, she continued to work as a kind of editor. She selected from Lagerfeld’s sketches and gave him notes, tempering his often “baroque” styles with chicer fabrics and more streamlined finishes. “I have always said that fashion should be as fresh as salad,” she once said. For his part, Lagerfeld remarked that Aghion taught him much about how to make clothing both lively and marketable. Each day after work they both drove to her apartment to discuss the collection; he called his time at Chloé his “happiest, most carefree years.”

Lagerfeld remained there for twenty years and returned to design a few seasons in the Nineties, when he was steering Fendi and Chanel. The curators consider his association with the label to be so important that they have pulled the title from a line of Lagerfeld’s, not Aghion’s. On display are his Mary Quant and Pucci tributes from the Sixties, highlights from his surrealist run in the Eighties—when, with his “Angkor” dress from the summer of 1983, he transformed the torso into a cello—and his designs for the whimsical haute-girly-girl white eyelet frills and flowy silk blouses with scalloped edges that Chloé is still known for. Some of Lagerfeld’s dresses are paired with his sketches, tidy in his early days and then later fabulously deranged, with thick crayon scribbles and collaged photos of ancient frescoes.

A bevy of young female designers eventually took the reins, beginning in the late Eighties with Martine Sitbon, who injected the brand, which had grown stuffy under Lagerfeld, with a bit of life. Sitbon sent the era’s supermodels—Linda Evangelista, Helena Christensen, Christy Turlington—down the runway in sexy garments inspired by the “queer and retro side” and “trans culture” of Paris’s Pigalle district. She also referenced older Chloé codes: under her direction, Lagerfeld’s sequined surrealism was reinterpreted through sheer dresses with erogenous zones covered in paillettes. (Shortly before this period Aghion sold her stake in the company to Dunhill Holdings, now Richemont, a conglomerate that owns luxury brands like Alaïa and Van Cleef and Arpels.)

Advertisement

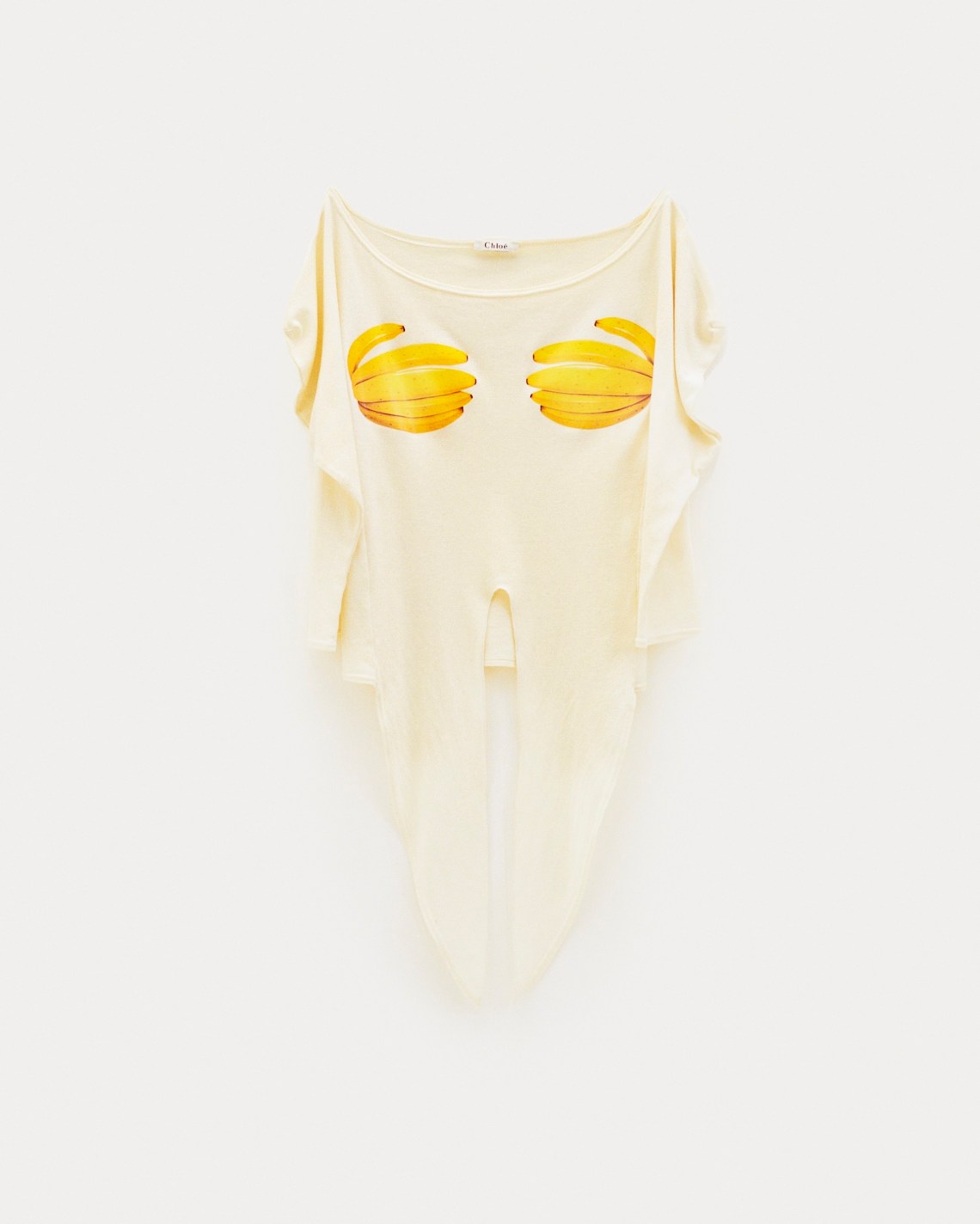

After Sitbon departed in 1992, Lagerfeld returned to the helm until 1997, when Stella McCartney took over. “I knew it would take a big name to replace me at Chloé,” Lagerfeld said at the time, “but I thought it would be in fashion, not music.” Fresh out of Central Saint Martins, the twenty-five-year-old McCartney was an inspired pick, not just because her father is Paul and her friends Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, and Yasmin Le Bon all walked in her undergraduate thesis show, but because she understood how to confect high fashion and youth culture—with, for example, tiny, shiny party dresses for her and her celebrity friends. It was “a time when Paris fashion houses really weren’t designing clothes that women could wear,” McCartney said, echoing Aghion, and she sought to remedy that with such garments an orange-blown blouse that fuses “wearability” and “coolness” and a T-shirt with bananas printed over the boobs along with the words “keep your bananas off my melons.”

Succeeding McCartney was her Saint Martins classmate and former design assistant Phoebe Philo, who to this day has a cultlike following. So-called Philophiles buy and sell archival pieces from the designer’s time at Celine, where she made Birkenstocks cool and pioneered the minimal-chic look that still rules the racks at Zara. Philo was also the progenitor of the current trend for “quiet luxury,” in which the obviously luxe—flashy logos, furs—is eschewed for a vicuña fiber baseball cap. But at Chloé, her first job as creative director, her designs were far more boho, feminine, and airy. The advertisements for the Jewish Museum show feature her gossamer blue dress from 2004 laid out almost in the style of a xeroxed image.

Philo’s popularity endures in part because of the idea that she designs for powerful women, making them feel sexy and in charge without sacrificing practicalities—an unusual perspective in a fashion world dominated by male designers who are often uninterested in fitting clothes to the female body. It is not so easy to place Philo—who has become known for her androgynous silhouette, often tucks her hair into turtlenecks, and wears pants and Stan Smith sneakers—in this lineage of one of fashion’s most unabashedly feminine outlets. But she hearkens back to the early days of Chloé: garments for women with things to do who want to look beautiful doing them. In the exhibition catalog, Choghakate Kazarian writes that Aghion intended to create “luxury ready-to-wear combining high end materials and savoir faire with light shapes for active women.” Something similar attracts the cult of Philo today, though her woman is a bit more businesslike and severe.

*

By focusing on Chloé as a whole, and all the big names attached to it over the decades, the Jewish Museum has tried to appeal to as big an audience as possible. But celebrity clouds Aghion’s achievement. One room in the show, beautifully designed by Elliott Barnes, features blouses arranged in an ombré of white to tan to brown—a gradient that supposedly evokes Egyptian sand. Not much else about Aghion herself is explored or even referenced. Photos from her first shows feel like a prologue to Lagerfeld’s and Philo’s work. Her name serves as little more than justification for the Jewish Museum to host the show.

Kazarian’s catalog essay, on the other hand, provides a range of useful details about Aghion’s life and social setting, as well as her husband’s. (Raymond was one of the first Egyptian Jews to attempt to mediate peace between the Arab world and Israel after the Six-Day War in 1967.) Numerous scholars—even Lagerfeld’s biographer Alfons Kaiser—discuss Aghion’s politics and social world and how they informed her business, but the curators have missed the opportunity to examine her life and work as a departure from the norms of Paris and the fashion world at large. The catalog explains that Aghion was among the first designers in Paris to move her base to the left bank but doesn’t discuss her influence on those who followed suit, like Yves Saint Laurent and Sonia Rykiel.

One wonders why an exhibition at the Jewish Museum has more time for a room full of Philo’s blouses than for an account of Aghion’s life as an Egyptian Jew. Perhaps the absence of any clothing samples from the early days of Chloé compelled the curators to downplay this period, but it could have been interesting to delve deeper into the world that surrounded the brand’s creation. A recent Schiaparelli exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs foregrounded her collaborations with artists: a portrait by Picasso of Éluard’s wife in a Schiaparelli outfit was hung near jewelry designed for the brand by Giacometti, Man Ray, and Dalí. (Although that exhibition chose to elide Schiaparelli’s collaboration with the Vichy government.) What of Aghion’s demimonde? Some poems from her friends are hung in the opening area, but they’re easy to pass by to get closer to the far more eye-catching clothes.

There is only one dress codesigned by Aghion and Maxime de la Falaise in the exhibition: a tan jersey cashmere wool shirt-dress that is simple without being stoic, feminine but not frivolous. It is an elegant, serious woman’s outfit. It is lined with a printed silk twill for comfort and a bit of interest, and it can be nipped in at the waist or worn loose. It is easy to imagine its wearer fitting in across social milieus—elegant enough for the Avenue Montaigne but sufficiently staid for Hillel Schwartz and his crowd of Cairene Marxists. One wonders what the exhibition would feel like if it were tailored to the woman in that dress.