Mugshots of late capitalism, I caught my tongue murmuring: in these galleries you face an era’s ID. I was wandering through “What Happened,” an exhibition in London of paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures created over the past three decades by Nicole Eisenman. What prompted my resort to that loose period label? Since her graduation from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1987, the imagined publics toward which Eisenman has directed her copious, convivial energies have grown in scale. Her notional constituency, cartooning and muraling in 1990s Manhattan, was fiercely local, an East Village queer scene. The canvases and sculptures of the middle-aged artist, however, have at times amounted to satirical State of the Union addresses. The Triumph of Poverty (2009; see below) led the way, painted after the subprime mortgage scandal and the financial crisis it catalyzed: a composition nearly seven feet wide presenting a motley march of the repossessed—some pitiable, others grotesque—stalled on the edge of town in front of a clapboard bungalow on the point of being arsoned. Presiding, but most clueless of all, is a banker whose pants have collapsed to reveal that he stands literally ass-backward. More recently and yet larger, there has been Dark Light (2017), featuring fossil fuel diehards before pipes that gush carbon-dense blackness, and, the year after the 2016 presidential election, a ship of fools about to hit the rapids entitled Heading Down River on the USS J-Bone of an Ass.

Witnessing the profit system trip over its own feet, we might reach for a conceptual scapegoat: in this sense, another symptom of “late” (or “late-stage”) capitalism would be that the owners of Eisenman’s satire of repossession derive their wealth from a major lending company. The originally Marxian category has also—ever since its citation in the title of a 1991 book by Fredric Jameson—been extended from public to aesthetic affairs, on the premise that art obeys a recursive pattern similar to other forms of production when it settles for mash-up tactics, with image makers promiscuously referencing their historical forebears. The insertion in Eisenman’s Triumph of a row of figures transcribed from Bruegel would be one small instance of this, in a body of exhibited work that suavely nods to Ingres, Picasso, Philip Guston, Marvel Comics, Renaissance triptychs, German Expressionism, and much else. Eisenman’s high-spirited studio practice equivocates on questions implicit in much of the recent figuration spurred by her example. Given that there is a vigorous market in the 2020s for culturally freighted wall hangings, should painters look to art history for legitimation by name-dropping, for angles of critical attack, or simply for reassurance that their skills have a structural place in society?

But in truth, it was hardly these debating points that guided me as I chanced on my periodizing phrase. More, I was tempted by the word late. For the hour generally is late in Eisenman’s pictorial world, the palette prevailingly fuscous. We find ourselves—in several memorable canvases produced in her early forties—in some packed 1:00 AM beer garden, amid the ripped, the randy, and the maudlin. We meet a similar Manhattan gang, now soberer in purpose, maintaining an all-night protest to demand police defunding in The Abolitionists in the Park (2020–2021), the most grandiose but perhaps the lowest lit of her big public paintings. Others among them also yank the tone down: the fierce surge of black paint in Dark Light, a starlit sky that is the ship-of-fools painting’s most inventive passage, Triumph’s patchwork of yellow-greens and orange-puces that is as heavy, queasy, and warm as the contents of a compost bin. Alternately, when—in a suite of big canvases from the mid-2010s—Eisenman pictures average Americans in their privacy zones, she visualizes bleary, screen-zonked saddos. She wants caringly to enter their lonely rooms, but her curiosity is fretful. Late tips into too late, implying impending crisis. Time to shut it, boy. Time running out for orders to the bar, time running out for the US to change course. The temper the exhibition communicates is at once effusive and foreboding.

The less tomorrow becomes thinkable, the more license to splurge today: a system’s impending demise may reveal itself in feverish hilarity. The daring of many of these pieces is the daring of buying up every pigment, medium, and brush in the paint store and getting them to chime polyphonically. If chromatic extravaganzas such as The Abolitionists or Beer Garden with A.K. (2009) stay readable, that is thanks to Eisenman’s consummate assurance as a figure drawer. She sprang out of RISD fully prepared, it seems, to rotate human bodies in every conceivable contortion and combination. In those early days her imagining was near monochrome: brown lines and orange washes predominated, lending a frowsty, preloved look both to her cartooning and to the ephemeral murals she volunteered to daub on the walls of arts venues. (The exhibition features a video résumé of these, suggesting that underneath all the swanky turns at pastiche, her imaginative seedbed was 1930s public art commissioned via the WPA.) The dreams were of galumphing masses in motion: naked Amazonian females presided, here wreaking vengeance on males, there giving each other head or perhaps a helping hand.

Advertisement

Spiky cartoons and murals—for the 1995 Whitney Biennial, a visualization of that museum collapsed in ruins—allowed Eisenman to flaunt her picture-making skills in a milieu where their status was uncertain. In the metropolitan scene she entered after graduation, the view remained widespread that for art to face forward, it must somehow move on from the format of the easel painting. Feeding the skepticism was the sense that a tradition of salable wall hangings bearing a trenchantly masculine stamp served a capitalism so “late,” so grotesquely athwart our present needs, that it was overdue to expire. Could guerrilla warfare against that patriarchy help dispatch it? Queer imagery, in that case—work that mocked and upended gender stereotypes—was art’s ally, supposing art involved liberating multiple forms of human potential. “Angry and sad about how completely fucked up male privilege is,” Eisenman ran with this ethos, at once swaggeringly able and apt to switch the mocking mirror in her own direction, in the process acquiring some celebrity. To this day she keeps that faith, participating in a queer exhibiting collective indicatively named Ridykeulous.

But to walk through “What Happened” is to watch the 1990s recede like the memory of a wild evening. This is a show dominated by large easel paintings: those with the beer gardens were painted by a settled householder in the late 2000s, piecing together scenes from her boho youth. Back then she had also filled canvases, but in a Mannerist spirit—that is to say, with arch, fantastically contorted figure compositions that half taunted the viewer, What business have you to interpret me?

By Eisenman’s forties, her demeanor had altered. An inclusive entertainer had emerged. Witness Seder, a relatively modest—four-foot-wide—canvas from 2010 (see illustration on page 6). Here is the painter’s Jewish family gathered at their Passover table as if for a fond sitcom—eight oddballs, each summoned up in a separate language of texture and color, Eisenman’s brush staging further variety turns for the matzo the viewer’s own hands can be seen holding and for the early-Rothko-like swirls on the dining room’s far wall. This wry group portrait exemplifies what’s technically strong about Eisenman’s practice. She’s not an artist to look to for especially subtle or surprising mark making, in contrast to that slightly older voice in New York painting, Amy Sillman. But where she does—literally—draw the line, it holds firm. Her edges interlock with such panache. In Seder’s collage of personal memories we see the youngest child at table gleefully plunge her knife into a beet-topped gefilte fish that’s refracted through a wineglass: what a joy of invention, both comical and formal, has gone into that collision of incidents.

This communicative Eisenman has offered inspiration to younger artists, partly because her work readily lends itself to narrative readings—as she has explained, she is a psychiatrist’s daughter “from a line of people who dealt with stories”—but more generally through the sheer inquisitive buoyancy with which she has deployed paint to take on the world. Further eye-stopping details such as a cat in Weeks on the Train (2015) dimly glimpsed through a pet carrier’s mesh, or the fanatically rendered plastic of a TV’s rear cover in Reality Show (2022), advertise the incomparable versatility of oils—in the latter case, as an implicit riposte to the screen, the backlit pixels of which are now our pictorial norm. The taste for meticulous manufacture that is evident here has spread through the current vogue for figurative painting: it’s where Eisenman’s example has overlapped with that of Kerry James Marshall.

As art scene priorities have moved on from the 1990s, discourse about “queerness” has scrambled to keep in step, or so it appears from critics’ writings cited by Mark Godfrey, one of the exhibition’s curators, in his handsome catalog essay. Anything in Eisenman’s art, from its “sensuous tactility” to its “treatment of mundane details outside the painting’s focal point,” is claimed to be queer, while “the oscillation between texture and atmospheric mood” is said to generate “productive, queer friction.” The term resembles a once-turbulent weather front that has drifted out to sea and is, as the forecasters say, “losing definition.”

“I might use that word to describe myself but not my work,” Eisenman told an interlocutor who had sought her views on an “emerging queer aesthetic” in a 2019 discussion. Tactility, it’s true, is a value she currently reaches for to rationalize the case for her art. By foregrounding surface textures and that ready vessel for empathy, the figure, she hopes it will establish “a deep connection with the viewer.” But this is not to promote an identity constituency: rather, it’s to bypass demarcations. The only category in her sights nowadays would seem to be the human species.

Advertisement

A kind of sculptural manifesto for this forms a centerpiece to the show. Maker’s Muck (2022) invites us to walk around an outsize seated figure, a crude plaster model bearing no face and only minimal signs of female identity. On sprung-hinged wrists, her hands close in on a large dollop of moist clay that a motor rotates and a feed pipe keeps watered. On every side of this allegory of the eternally form-creating human being, excrescences are scattered—sundry small figures and constructions in every medium from plywood to bronze, polystyrene to terra-cotta. The ensemble is at once imposing and banteringly absurd, showing creativity and detritus as two sides of one coin. But to this viewer, at least, the folly is the wrong side of foolish. Despite its would-be facelessness, the main figure inevitably points back to Eisenman—as if to a twenty-first-century Picasso astonished at her own inventive fertility—revealing a tail-chasing self-regard to which she is too susceptible.

It repeatedly leads to poor judgments of scale, as in japes about her own career (e.g., the painting From Success to Obscurity, 2004), better suited to Instagram than to foyer-filling expanses of canvas. Nonetheless, canvas, on the evidence of this show, remains a happier arena for her than three dimensions, for all her growing interest in sculpture over recent years. The omnivorous grabbiness—every item in the art store and in the US public realm—remains a kind of marvel, as long as the trophies are compressed down flat. In actual space, the must-also-haves—that wheel-turning motor, that water pipe, or, say, the cuckoo clock imported into a 2018 plinth-mounted bust named Eagle—become laborious lumber, the heavier for the echoes such material bears of many a preceding sculptural practice.

Yet Eisenman’s will to investigate and to generate presents an example that overall is inspiring. Her force of mind, both aesthetic and political, is magnetic, although all I know of history tells me that even now, a young artist will somewhere be plotting a pushback against her warmhearted humanism, deeming it inadequate to our present late hour. I am left asking myself what—edification aside—I took away from “What Happened.” Not meanings, I find. I think of the canvas Hunting (2000), a fable of the frozen north featuring snow-suited, spear-wielding Amazons bearing down on the wreck of a helicopter and its stranded male crew. The bizarrerie of the scenario feels swaggeringly cryptic, but that in no way diminishes my relish for Eisenman’s orchestration of linear rhythms and a fastidious color scheme.

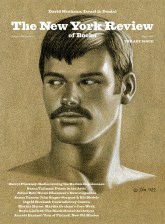

From that four-and-a-half-foot-wide Arctic fantasia I am led back to another, a more-than-ten-foot-high painting that Eisenman produced in 2019 in response to a sculpture of her own devising. Both this 2D and that 3D piece belong, along with many monotypes, to a suite of experiments with the form of the human head, on which she began working in 2012 and which has constituted her formally boldest art to date. In the case of the towering canvas, she recklessly chopped and reshuffled ice-white building blocks of flesh to yield a ghostly grim visage that juts out against shiver-inducing blues, lemons, and purples. Eisenman’s free play when working on the head suite spawned monsters: having fashioned them, she asked a writer friend to develop identities for each piece, shuttling them on a reverse journey from invention to intention. In the case of the great cranial iceberg, the title adopted became Econ Prof—essence, we are to imagine, of Milton Friedman, Alan Greenspan, Paul Volcker. Their mugshots distilled to one image: moving my eyes its way, I recall what first moved my tongue.