For most composers, the only way to learn how to write operas is to write operas. I may not love every one of the works that W.A. Mozart dashed off during his adolescence or that Giuseppe Verdi wrote during his so-called galley years, when he compared his crushing workload to that of a galley slave, but the steady increase in the quality of both composers’ operas suggests that neither could have written his midcareer masterpieces without taking every painstaking step along the way.

The Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho, who died in 2023 at the age of seventy, is a rare exception to this rule: she waited until she was almost fifty to attempt an opera, and by her own admission she hadn’t seriously considered working in the genre until early middle age. When one considers Saariaho’s relatively late start and her hesitance about opera as a medium, it’s all the more astonishing that her L’Amour de loin (2000) is a transcendent masterpiece of seemingly limitless beauty and depth. I can’t think of another composer other than Alban Berg, with Wozzeck (1925), who jumped straight to a full-scale opera mid-career and got so many things right.

Throughout her four-decade career, Saariaho quietly subverted expectations at every turn. Her training took place largely within the walled citadels of the European avant-garde: she studied with the serialist Klaus Huber in Freiburg, attended the new-music summer courses in Darmstadt, and worked for a time at IRCAM, Pierre Boulez’s electronic-music stronghold in Paris. But with her knack for plucking sound after sound with uncanny ease out of some deep well of silence, Saariaho could only fulfill her potential by gaining access to the orchestra, with all its infinitesimally subtle textural possibilities. And so she made the fairly unusual leap from the insular circuit of European new music to the somewhat wider world of symphony orchestras, becoming a beloved mainstay even among American ensembles that typically preferred their European composers to be male, tonal, and dead.

L’Amour de loin upends expectations of what a composer’s first opera is supposed to be: its musical language is somehow both austere and voluptuously beautiful, and time unfurls with a luminous slowness; it has a patience and inexorability that one finds in precious few operas outside of Parsifal (1882), Richard Wagner’s final opera. This degree of temporal dilation is generally a hallmark not of ruddy middle age but of “late style,” that quasi-mystical mode that composers mythically attain only through decades of hard experience, combined with a touch of senility or syphilis. It feels appropriate that in this regard, too, Saariaho subverted expectations: nearly two decades after L’Amour de loin, just when she might have been expected to slow down into a commodious or self-indulgent late style, she did the opposite. Her final opera, Innocence (2021), a fierce, pitiless excavation of the festering aftermath of a school shooting, sounds as if it were shot out of a cannon.

It’s illuminating to listen to Saariaho’s first opera alongside her last one: her winding evolution through the intervening two decades can tell us a lot about what is gained and what is lost when a composer trades a dramaturgy founded on the patient, organic development of musical materials—as in L’Amour de loin—for the hard-boiled, somewhat more conventionally “theatrical” dramaturgy of Innocence.

The essential mood of Saariaho’s music is one of expectation. The director Peter Sellars, one of her most important collaborators, has likened this quality to “that weird thing you feel in the air before it is going to rain, and you say oh, it is going to rain…It is a knowledge that goes deeper than anything you were ever taught.”1 Saariaho has written entire pieces that inhabit this precarious state of ever-accumulating energy: the air is charged and heavy and crackles with an elusive electricity, even if the storm doesn’t always arrive.

This pervasive aura is both a strength and, at times, a limitation. In Saariaho’s most successful works, her music’s heightened, attentive quality becomes almost a holiness: it is a kind of prayer, a holding oneself open to some mysterious force that refuses to reveal itself fully. In her weaker ones, this quality of perpetual, never-satisfied expectation can grow a little wearying; her music is not entirely free of the generalized anxiety disorder that has afflicted many European modernist composers for the past century. The condition of waiting is a hard one to maintain in a work of art: its meaningfulness flickers by its very nature; faith is reliably attended by doubt. The artist must sustain the sense that whatever is being waited for, whatever lies just out of sight, is special enough that it deserves to be shrouded in veil upon veil.

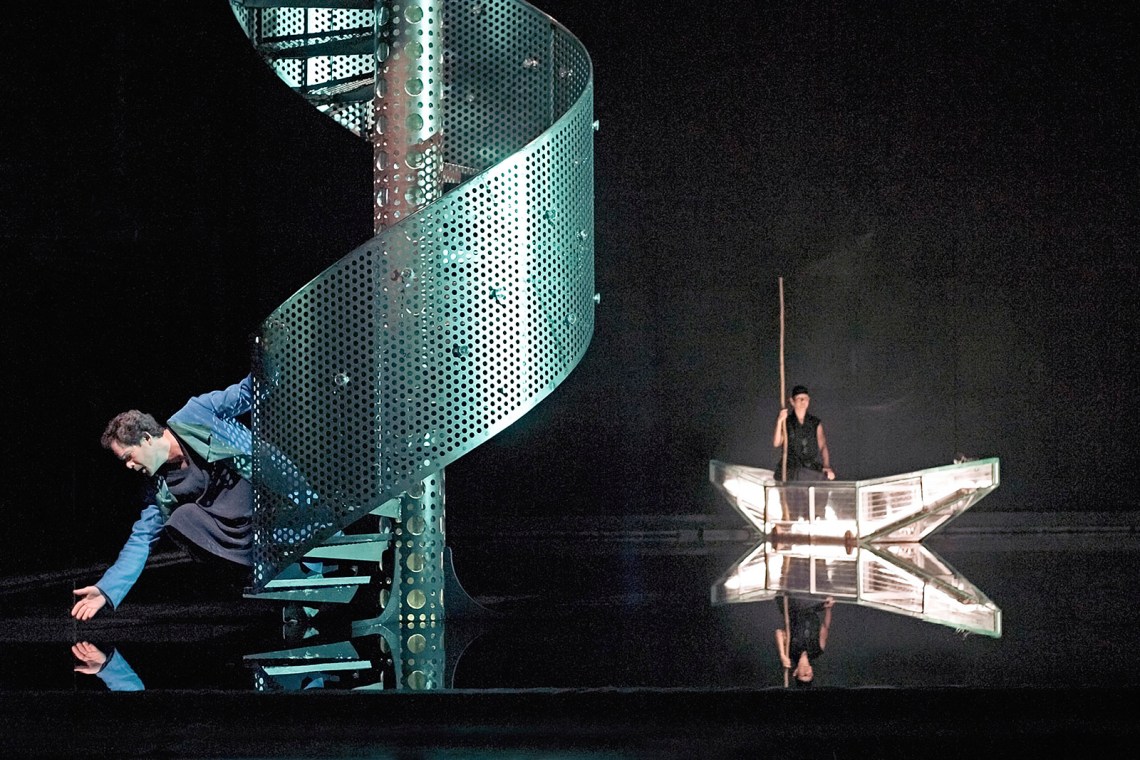

This is part of what makes L’Amour de loin such a triumph: the source of the characters’ hopes and expectations, a love affair that begins as an audacious leap of imagination, feels utterly worth waiting for. The opera, which features a masterfully light-footed libretto by the Lebanese-French writer Amin Maalouf, tells the story of the medieval troubadour Jaufré Rudel, a historical figure—a number of his poems and songs have survived—but one who is known today largely through a mythologizing biography. According to this fictionalized vida, Jaufré fell in love with the Countess of Tripoli purely on the basis of descriptions of her he heard from a wandering pilgrim. The countess inspired many of Jaufré’s songs, including an ode to his faraway love, his “amor de lonh.” Eventually, consumed by longing, Jaufré made the fatal mistake of traveling to meet his beloved in person. During the sea voyage he fell dangerously ill; upon his arrival in Tripoli, he died in her arms. The countess, moved by his passion, committed herself to life as a nun.

Advertisement

The work’s very title, “love from afar,” contains a playful critique of the Romantic-era warhorses that form the backbone of the operatic repertoire: the operas of Wagner, Giacomo Puccini, and Georges Bizet, among others, with their loud, sweaty, amorous exclamations, depict nothing if not “love from up close.” The heightened yet fragile mood of Saariaho’s music—it’s going to rain, but it is not raining yet—required a different kind of story. There is a reticence to her music, an unwillingness to trespass, to mistakenly use her sacred medium to say something trivial. It’s no coincidence that she picked a tale whose tragedy hinges on a heedless attempt to transform the ideal into the real.

There are only three characters in L’Amour de loin: Jaufré, the troubadour; Clémence, the countess; and the Pilgrim, who travels back and forth, relaying messages between the long-distance lovers. The composer has suggested that the characters of L’Amour de loin embody different aspects of her personality: “The troubadour Jaufré was the musician; Clémence was the nostalgic woman living far from her birthplace; and the Pilgrim wanted to bring these two fates together.” We might understand this affinity not only on a biographical level but also a musical one: the interpersonal geometry of these three characters manifests the delicate tensions that animate Saariaho’s music. Jaufré, consumed and obsessed by a yearning that seems equal parts spiritual and sensual, struggles to find a means of expressing his love without betraying its essence; Clémence spends much of the opera in the familiar Saariaho condition of prolonged expectation; and the Pilgrim enacts the artist’s daily labor, the ceaseless and frequently exhausting work of mediating between those contrasting impulses, seeking to maintain a fragile equilibrium.

L’Amour de loin succeeds largely because Saariaho trusted the musical logic she had already developed in her orchestral and chamber works, rather than accepting any prefabricated notions of operatic pacing. She was lucky to have collaborators who urged her to rely on her deeper instincts. Early on she planned for the opera to feature two couples: the hopelessly idealistic Jaufré and Clémence would be balanced by “an earthly, even silly, couple” who would serve as a comic foil—a familiar double-date schema that can be found in plenty of canonical operas, from Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail to Puccini’s La Bohème. In an early meeting about the piece’s structure, Sellars (who directed the opera’s first production) asked Saariaho to speak the opera’s synopsis aloud. After she did, Sellars, like an expert therapist, pointed out that “at no point had [Saariaho] mentioned anybody other than the troubadour Jaufré, Clémence, and the Pilgrim.” The extraneous characters were jettisoned, and the cast was honed to its Jungian essence.

The music in L’Amour de loin moves only reluctantly from sound to sound; it wants to luxuriate in the gorgeousness of every texture for as long as possible. Every musical work has an inner acoustic distinct from the acoustic of the space in which it’s performed, and the acoustic of L’Amour de loin is as resonant as a cathedral: practically every bar features some lingering after-sound—a pool of resonance from the small tuned cymbals known as crotales, a glowing contrail in the strings. And yet the orchestration of long stretches of the opera is notably sparse: the stunningly beautiful final section of the second act features little other than strings, chiming percussion, harp, and a distant chorus of sopranos and altos. This magical quality of simultaneous lushness and spareness perfectly mirrors the work’s libretto, which is both feverishly sensual and ascetically self-denying.

Saariaho also made the wise decision to treat one of Jaufré Rudel’s actual compositions, “Lanquan li jorn son lonc en mai” (“When the days are long in May”), as the opera’s central musical thread. Jaufré’s pulseless, languorously meandering melody is sometimes quoted at length, but even when it’s not referenced directly, its medieval idiom serves as a template for the opera’s vocal writing. The presence of this song has a subtly defamiliarizing effect: it belongs neither to the twentieth-century avant-garde nor to any operatic or orchestral tradition. That distance enables Saariaho to mine the song for a new musical language.

Advertisement

It’s fitting that L’Amour de loin had its premiere in 2000: many twenty-first-century composers followed Saariaho’s lead and wrote operas that did not fit into the illusory stylistic categories (serialism, spectralism, new complexity, new Romanticism) that dominated contemporary classical music in the latter half of the twentieth century. But in its patience, its hard-earned freedom, and its sheer loveliness, L’Amour de loin’s standard proved hard to match.

What’s a composer to do after writing so consummately beautiful a first opera? One answer would be to never write another, and indeed Saariaho assumed, throughout the creation of L’Amour de loin, that it was “the only opera I would ever compose.” But like many composers, she found herself nourished by—or is it addicted to?—the camaraderie and sense of shared mission that arise through the process of bringing an opera to the stage. And so, to her evident surprise, Saariaho composed five more works of music theater over the following two decades.

L’Amour de loin strikes a rare balance: it is equally satisfying on an earthly plane and a spiritual one, as a ravishing aural experience and as an expression of a kind of religious fervor. To my ears, Saariaho never achieved this equilibrium in her later operas, which toggle unevenly between two competing tendencies. At times her music manifests a severe asceticism, a desire to achieve transcendence through a musical starvation diet: in such pieces, the landscape is one of parched string harmonics, breathy flute sounds, wind chimes that shimmer like a mirage, singing that keeps washing ashore into speech—no carbohydrates allowed. Such pieces have taken as their protagonists either pioneers of rigorous spiritual discipline, as in La Passion de Simone (2006), a chilly oratorio based on the life of the philosopher Simone Weil, or disembodied ghosts and celestial beings, as in Only the Sound Remains (2015), a double bill of two one-act operas, based on Japanese Noh plays, both of which concern troubled spirits who visit the land of the living to make demands that might bring them peace. These works contain plenty of impressive passages, but their measured aloofness frequently tips into sterility, especially next to an opera like L’Amour de loin, in which every note is suffused with radiance and joy.

Elsewhere, seemingly in revolt against her own habit of monastic austerity, Saariaho has sought out stories of overtly social relevance, and in such pieces her music is often earthy, violent, and dense. Her first opera in this mode was Adriana Mater (2006), a bleak tale of a woman who gives birth to a son after being raped in a city torn by war; the work’s drama hinges on the son’s anguished vacillation between the desire to murder his father and an inner need to forgive him. (There is one Saariaho opera from 2010, Émilie, that I have never encountered in performance and that has not yet been commercially recorded.)

Saariaho’s last opera, Innocence, falls firmly into the socially realistic camp, but where Adriana Mater still bears traces of the meditative, slowly unfolding timescale of L’Amour de loin, Innocence is a ferociously focused work of theater that’s blisteringly hot to the touch. In a career full of graceful, unexpected swerves, Saariaho had one more surprise in store: just as L’Amour de loin sounds nothing like a first opera, Innocence sounds nothing like a final one. It announces the touch of an artist who seems almost to be aging in reverse, who still has so much left to say.

When I taught Innocence in a college course earlier this year, some students found it questionable, and even a little irresponsible, to set an opera about a school shooting anywhere other than the United States. I was inclined to agree: of course America’s lunatic gun policies make mass shootings more likely here, by many orders of magnitude, than practically anywhere else in the world. And yet part of the power of Innocence is the shock that the characters undergo when confronted with the reality that a mass slaughter, however unlikely it may be, can befall even a seemingly progressive school in a cosmopolitan center like Helsinki. I saw Innocence in the Netherlands, a country whose firearm regulations are not only stricter than those in the US but also stricter than Finland’s. The week before opening night, a medical student at Erasmus University in Rotterdam went on a shooting rampage that left three people dead, including a fourteen-year-old girl.

Innocence features an original Finnish-language libretto by the novelist and playwright Sofi Oksanen as well as multilingual contributions by the dramaturge and director Aleksi Barrière, who is also Saariaho’s son. The narrative is taut, straightforward, and immaculately constructed. At the wedding of a young Finnish man to a young Romanian woman, one of the waitresses, who has been hired as a last-minute replacement for a sick colleague, realizes the groom is the brother of the man who killed her daughter in a school shooting a decade before. The waitress also learns that the bride, who has moved to Finland only recently, is unaware of her in-laws’ disturbing family history. The ever-more-chaotic wedding scenes are interspersed with reenactments of the day of the shooting, as recounted by a teacher and a number of the students, most of them alive and profoundly traumatized, one of them an unforgettably eloquent ghost.2

Saariaho has cited Richard Strauss’s Elektra (1909) as a model for Innocence, and her opera resembles Strauss’s not only in its scope—both are scored for large orchestra and last roughly one hour and forty minutes, with no intermission—but also in its fixation on the return of old disasters, the grim and inescapable consequences of long-buried violence. Her treatment of the orchestra, however, could hardly be more different from Strauss’s bludgeoning, irresistibly maximalist approach: in Innocence, Saariaho hones the orchestra to a sharp point, wielding chamber-scale subsets of instruments like lasers. Leaf through the score of Innocence and you’ll find very few sections where a majority of the orchestra is playing at once. Even so, there are frequently at least three textural strata—foreground, middle ground, background—differentiated with absolute mastery, so that individual instruments leap out of the texture. Throughout the evening, the celeste’s shivering cascades signal the rippling emergence of a world of memory. The trumpet’s Miles Davis–esque “rips,” by contrast, constitute violent, recurrent jolts of oblivion, the self-obliterating shudders of trauma. I would gladly go to a concert that consisted only of Innocence’s orchestral score, without any of the soloists’ vocal lines.

But there is some memorable vocal writing, too: Markéta, the murdered daughter of the Waitress, returns as a ghost to sing a series of guttingly beautiful duets with her mother. In the score, Markéta is listed not as any particular voice type but simply as a “folk singer,” a description that doesn’t prepare the listener for the unearthly brightness that Vilma Jää brought to the part, both in the opera’s premiere in Aix-en-Provence in July 2021 and in the Amsterdam revival. Saariaho evidently trusted Jää, who is also a composer and songwriter, to add a unique flavor to the score: Markéta’s music includes a number of cadenzas, which invite the singer to improvise within a given harmonic landscape. The flexibility granted to this role was palpable in Jää’s searingly confident performance, which raised goosebumps that refused to subside for as long as her music lasted.

The tragedy at the heart of Innocence takes place at an international school, and the opera’s libretto is a mosaic of no fewer than nine languages—English, Finnish, French, Czech, German, Swedish, Romanian, Spanish, and Greek. The title page of the score notes, unusually, that “the communication language is English.” If “communication” in this opera is done in English, what exactly is happening when the other languages are spoken? Something other than communication, evidently: Saariaho and Oksanen treat the mass shooting’s traumatic impact as a disaster not unlike the biblical punishment of the builders of the Tower of Babel, which sends them scattering into the prisons of their incommunicable experience. Some of the victims in Innocence have been banished not only from the shared realm of English, the corporate Esperanto of our time, but from music itself: several of the most severely traumatized students speak rather than sing throughout the entire opera.

This is an intriguing conceit, but it doesn’t entirely work in practice. Saariaho is considerably more comfortable with some languages than others, and in a couple of cases she defaults to clunky linguistic stereotypes; the German student communicates exclusively in a jerky, spasmodic, not particularly imaginative Sprechstimme. And Saariaho’s setting of English, which makes up a significant percentage of the libretto, is worlds away from her magnificent, expansive approach to French; she seems to accept the English language’s fabled awkwardness at face value, frequently composing lines of a generic angularity, not quite close enough to speech rhythms to sound idiomatic yet also not far enough away from those rhythms for the music to take flight. When the wedding guests bicker in English, one might as well be listening to any competent European modernist composer; nothing in these sections suggests an artist of Saariaho’s stature. The effect of chaotic linguistic dispersion is also somewhat undercut by the sophistication and first-worldness of the entire situation. In one scene, the Bridegroom pivots nimbly between Finnish and English, then addresses another character in suave, unblemished French. I felt as though I were in the lobby of an exclusive Swiss ski lodge.

Innocence displays Saariaho at her most masterful but not her most profound. It is a fiendishly effective piece of prestige TV–style drama, but there’s something of a disconnect between the functional, quotidian language of Oksanen’s libretto and the specific nature of Saariaho’s musical gifts. The most surreally dreamlike sections of Innocence, in particular the encounters between the ghostly Markéta and her mother, are by far the most musically potent, but they constitute a relatively small proportion of the work. The musical tone of the rest of the opera is depressingly unvaried: even in moments when the libretto seems to demand a palpable change of character, Saariaho’s music is unwilling to oblige. When a priest, the only person willing to befriend the shooter’s parents after the massacre, tries to comfort the Mother-in-Law, he speaks words of genuine tenderness and care, but Saariaho sets his text to a dully meandering, low-lying vocal line that doggedly drains the words of their meaning.

In the opera’s final scene, which bears an unexpected resemblance to the epilogue of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, the surviving students share anecdotes that suggest definite progress out of the imprisonment of trauma. One student declares that the experience of the shooting set her on the path to becoming a doctor; another announces that he recently found himself able to appreciate his daughter’s ice-skating performance, rather than merely obsessing over where the ice rink’s exits were located; and a third says simply, “I will start over, and I believe I am able to do it.” Nothing in Oksanen’s libretto suggests that she is mocking the students for daring to express a modicum of hope, but Saariaho undercuts their sentiments with bland, vaguely anxious music: they might as well be announcing their hopelessness and helplessness again, as they’ve done throughout the piece. That poor German student is stuck blaring his Schoenbergian Sprechstimme to the last syllable.

Saariaho has a habit of writing curiously counterintuitive expressive markings: the ominous, uneasy music at the start of the opera’s second scene, “The Wedding,” is marked molto giocoso, espressivo (very playful, expressive); near the end of the opera, a briskly angular sixteenth-note line in the piano is marked triste (sad). When I picture myself in the performers’ shoes, it’s hard for me to imagine making the former moment sound playful and expressive or the latter moment sad. I’m inclined to think of such markings as somewhat aspirational: Saariaho knows that the musical mood in such moments is a tad unspecific, so she leans on the verbal instruction rather than the expressive power of the notes themselves.

But in Innocence’s final minutes, she reminds us of the power of her artistry. The opera ends with Markéta asking her mother to let her go, to finally give up the compulsive rituals of remembrance that she has kept up for a decade. It is a moment that gathers together several of the central preoccupations of Saariaho’s operas: like the spirits in Only the Sound Remains, Markéta must return to the border of the living and the dead to ask for freedom; and what is this music if not a final expression of love from afar?

The scene could hardly be more emotionally loaded, but Saariaho musicalizes it with masterly restraint. As Markéta sings what could almost be a lullaby, her voice is immersed in a sound world that no other composer could have crafted: the complex overtones of chiming crotales hang in the air, smokelike portals to an alternate world; a piccolo wanders through the texture like a weary pilgrim; and then there are those inimitable Saariaho strings, high and songful, their harmonics gathering into slender sheets of light, shedding and shedding an inscrutable radiance.

—This is the second of two articles.

-

1

I’m currently collaborating with Sellars on my latest piece, Music for New Bodies. ↩

-

2

For a discussion of George Benjamin and Martin Crimp’s Picture a day like this, another contemporary opera about a mother grieving the loss of a child, see my “Alone in Paradise,” The New York Review, March 7, 2024. ↩