1.

Subject of poetasters, the Paradisal Isles! Italicized scrolls with f’s for s’s, whose scripts mimic their vegetation, letters hooked like the beaks of parrots or the coil of an overseer’s whip. The Hebrides, the Hesperides, the Cyclades, the Bahamas, all, being islands, have inspired a dipping rhythmic prose and florid verse, the exultations of discovery. These cartographical prints from the past held the excitement of sea battles and private treasures for us as West Indian schoolboys, unfurling to an imagined bristling of parchment with the names of Sir Francis Drake, Sir John Hawkins, Sir Henry Morgan, Captain Kidd, Anne Bonney, Bluebeard.

An excitable history settled down after all those adventures: the genocide of indigenous Indians, Carib, Taino, and Arawak; the brigands and buccaneers were followed by the domesticated monody of slavery then indenture; by cane planting and cane crop; by the pastoral of the sugar estate and its sentinel palms; by the life, formerly bloody and colorful, of sedate engravings.

Strange that these engravings should still look so sinister, their feathery heraldic fountains of palm and bamboo arching over shallow, rippling brooks, their light, always of mid-afternoon, suggesting languor, and beyond them the estate house with its jalousie windows and an empty verandah sad in its vacancy, or other pastorals, of Creole beauties in costume, of panniered donkeys prodded home by straw-hatted peasants, the donkeys’ hooves plodding to the meter of an era, a languorous, condescending prose.

To drive on dark narrow roads of broken asphalt with leaves of cocoa nearly touching the car, past black boulders with their thin cold streams, through unnamed clearings, and to pass sometimes those huge inverted cauldrons like World War II helmets, vats for boiling sugar, you come across startling ruins that, in their dankness, echo, like the gaping cauldrons, the sad history of West Indian slavery and indenture. In the gloom of cocoa groves, wild yam vines smother the abandoned machinery of rusted sugar mills, or the rails of trolleys that carried the reaped cane to the facto-ries. This is the smell of Krise’s anthology, the sickly sweet fragrance of molasses.

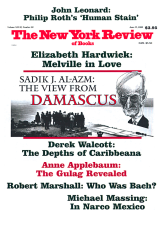

That past is scrupulously preserved in Caribbeana: An Anthology of English Literature of the West Indies, 1657-1777, which is edited and has an introduction by Thomas W. Krise. Mr. Krise describes the anthology as “a product of a passion for the history and culture of the West Indies.” The passion is evident in the excitement of his scholarship, admirable in the width of his research.

But reading these texts that are hallowed by age requires an adjustment of mood. One must read like the historian, without moral judgments, to translate oneself into the tone of their time, which means for most West Indians, certainly the African and Indian and Chinese, a return to illiteracy. This is why the idea of a West Indian history wobbles on its pivot and even collapses. How, for instance, is the descendant of slaves to read the following text with equanimity?

Negres

It has been accounted a strange thing, that the Negres, being more than double the numbers of the Christians that are there, and they accounted a bloody people, where they think they have power or advantages; and the more bloody, by how much they are more fearfull than others: that these should not commit some horrid massacre upon the Christians, thereby to enfranchise themselves, and become Masters of the Iland.

The “they” has become a “we,” so how is this to be taught, and if age gives the writing reverence simply because it is history, is the study of such texts and even their preservation worth it? Of course one can argue that it is worth it, because the achievement of the Caribbean would be in treating such texts for what they are at heart, not ignorant but innocent, and if innocent, innocuous. Their only value is in meter, in the elegance of their syntax, in the surge, rise, and burst of their theatrical rhetoric, in their reversible and interchangeable ironies. That is the Caribbean spirit, the gift of self-mockery, the delight in parody. That is the depth of Carnival, history as pappyshow and satire.

Toward the same old bad news that the collection brings the editor bravely assumes his shoot-the-messenger tone, and Mr. Krise does deserve someone’s gratitude, although it is hard to say whose. This is not a book that the West Indian reader is going to pluck from the shelf and devour with glee, although much of its tone is that of black farce. Mr. Krise, who, like sugar cane, was raised in St. Thomas, is an associate professor of English and executive officer of the Air Force Humanities Institute at the US Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs.

Among his selections, Richard Ligon’s A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (1657), in addition to giving a detailed account of plantation life, tells the story of Inkle and Yarico: Inkle is an Englishman who is saved by the Indian maiden Yarico, and who sells her into slavery when he is rescued. The popular story was turned into an opera by George Colman in 1787. There is Edmund Hickeringill’s hilarious and baffling Jamaica Viewed (1661), describing cocoa plantations and alligators in this sort of language: “Such is some mens prophane Boulimy & insatiable Poludipsie after Gold, through the depravement of their canine and pical Appetites.”

Advertisement

The writers soon sound like members of a club, especially the hatter Thomas Tryon, author of Friendly Advice to the Gentlemen-Planters of the East and West Indies (1684), and here described as a Pythagorean philosopher of vegetarianism and moderation, adopted for a time by Benjamin Franklin. Tryon provides a dialogue between a master and his slave in which each shares a rhythm of eloquence, in their debate on Christianity, but the slave’s voice slides into that of the master, the whole thing becoming a sermon against hypocrisy that is heavy going; a scouring of sinners with the inherent boredom of the evangelical.

Edward Ward’s A Trip to Jamaica (1698) now lifts the collection like a leavening, brisk wind as he catalogs the file of islands his ship passes:

Those we pas’d in sight of were, Deseado, a rare place for a Bird-catcher to be Governour of, Birds being the only Creatures by which ’tis Inhabited; Mountserat, Antego, [N]evis, possess’d by the English; St. Christophers, by half English half French; Rodunda, an uninhabitable high Rock…

And this is his destination, Jamaica, in his view not the earthly paradise but

the Dunghill of the Universe, the Refuse of the whole Creation, the Clippings of the Elements, a shapeless pile of Rubbish confus’ly jumbl’d into an Emblem of the Chaos, neglected by Omnipotence when he form’d the World into its admirable Order.

The Speech of Mr. John Talbot Campo-bell (1736), supposedly a reply to The Speech of Moses Bon Sàam (1735), written in defense of slavery by a free Christian Negro, was almost certainly composed by the rector of St. John’s Church in Nevis, the Reverend Robert Robertson. In Campo-bell’s brisk autobiography, whose breathlessness has the pace of exaggeration, of improvisation, he is captured with his father at age seven and put on a slaver where very soon there is an unsuccessful insurrection by the slaves, many of whom are killed, while some, in fear of retribution, jump into the sea.

Then smallpox breaks out, decimating another hundred. The boy is sold to a Jamaican planter; his father, on his deathbed, begs him to preserve their tribal language, which the son honors by also acquiring two more African languages. The planter sends his own eldest son, who is about the same age as Campo-bell, to England, with Campo-bell in the role of valet, for an education at a grammar school in Yorkshire, at Oxford, and a stay in London until their twenty-first year, then travels through France and Holland and other countries. Campo-bell admonishes any misrepresentation of his service by stating: “I had never been treated like a Slave, and in all our Studies and Travels the young Gentleman used me rather as a Companion than a Servant.”

They return to Jamaica both aged twenty-five. There Campo-bell was freed; his old master died some weeks before he arrived, having left Campo-bell’s freedom in his will, and “also a Dwelling-house, and two Slaves of my own Colour to wait upon me.”

The alleged autobiography then digresses into pages of facts which lose their oral immediacy, the quality of speech, but there is a dandified distance that is chilling in its casualness. The rule of law protects the slaves from excessive cruelty; only four have died at the hands of planters, though Campo-bell gives examples of their theft, for which he himself sees that they are soundly whipped, a scene which, if Moses Bon Sàam had witnessed it, “cou’d not but have touch’d him to the Quick.”

Campo-bell argues that slaves are clothed and fed by their masters, that they were sold by their own countrymen, that their masters, because of taxes and natural disasters, cannot be rich. He enjoins his brother slaves not to listen to the destructive arguments of Moses Bon Sàam, who presents himself as their leader out of bondage, since they could never maintain the defense of the island from vengeful fleets even if they slaughtered their white masters, fled, and established themselves in the Jamaican mountains. His instruction soars:

Be wise then, my Countrymen, and listen no longer to the Suggestions of Moses Bon Sàam: Submit rather forthwith to the white People here. They are Englishmen, and Cruelty is no Part of their Character; I dare promise, your Lives under them will be safer, easier, and happier than ever they can be in these Mountains.

Had I not been sold from Africa myself, I should have been undone! whereas now the Reverse is happily my Lot!

Campo-bell buys some slaves for himself and treats them as decently as he has been treated.

Advertisement

Sentence after sentence the horror grinds on, devouring statistics as a sugar wheel threshes cane stalks:

And the Yearly Importation of Slaves from Africa into the same Islands (not including those that are re-exported on Account of the Assiento Contract, or otherwise) cannot be less than 15,000; to make up which Number there must, considering the many Negroes that die in the Passage, be upwards of 20,000 exported from Africa; and then as, by the common Computation, about two Fifths of the new-imported Negroes die in the Seasoning; and as the Decrease of the Negroes in Barbadoes, for Example (by which one may judge how it is in the other Sugar Colonies) requires an annual Supply of about 2800….

Imagine, making up his autobiography as he does Campo-bell’s, and catching the fever of his syntax, the Reverend Robertson, this man of the cloth in Nevis with his pinched, death’s-head face, the drift of wispy hair from his flecked skull and ears, his yellowing collar, and his pen scratching parchment the way a marsh egret rakes the sand for wriggling semi-colons, with his persuasions of the need for slavery:

Now, shou’d England, or any of those other Nations boggle at it, or fancy something iniquitous or wicked in it, and thereupon let drop their Share in this Slave-Trade, their Share of the Profits arising from it wou’d presently be lost, and (which must wound deeper) some other Nation or Nations of Consciences not so strait-lac’d wou’d presently gain the Whole, which wou’d destroy that general Balance of Trade (and, by Consequence, of Power) which wise Men think ought to be maintain’d in the World.

If we follow the standard concept of a literary tradition in our use of these texts, nearly all written by Englishmen, we arrive at an abyss, like one of those engravings in which the traveler is posed on the lip of a chasm or precipice with an awesome and inaccessible world beyond. The world behind the traveler, with its charted track, is recorded History. The vertiginous and trackless world opposite is part of the landscape, but the immense fissure that separates the traveler from the opposite world is not only the seismic crack made by the abolition of slavery but the mental division made by the necessary rejection of the formerly subdued. In other words, where does recent history begin?

This question expresses more than the bewilderment of the African or Amerindian victim. Europe can be thought of as a collection of tribes that however tenuously are one family, one tribe, and as such they can exchange castles and massacres as events of a common history and geography, but ethnically this is not true of those who would come to inherit the islands, captured on another continent, the land on which the traveler looks across the Atlantic chasm. Yet this is eventually wonderful, is in fact a complex benediction, because a people deprived of a history should come not to need it, and should in fact live by that daily reality which does not conjugate time, at least not by the traveler’s and explorer’s and missionary’s dial.

Some of these texts are eccentricities, the flourishes of amateurs delighting in rodomontade and pseudo-Miltonic trumpetings, but the desperate archivist, eager to find anything that will give the Caribbean past dignity from print, has presented them with exaggerated importance if not reverence. Confronted with them, with the phony elegance that plates their obscene horrors, is the descendant of the victim supposed to accept, because of the patina of time, i.e., history, the torturer as his ancestor? Is he supposed to accept that these documents are the beginning of our literature in English? If any had the stature of Anglo-Saxon poetry then it may be fair for an Anglo-Saxon to claim them as a heritage, but they are too provincial, too pompous. They do not, as great poetry does, annihilate race and the vanity of political power. Their lesson is the need for the transcendence of genius, a genius that will come in a common language. Here in these silhouettes are the ancestors of C.L.R. James, Chamoiseau, and Naipaul.

As soon as Caliban speaks his first sentence in the language of Prospero, he is making history and literary history. But is that history the perpetuation of Prospero’s literature or the beginning of Caliban’s? The anthology includes a Latin ode by Francis Williams (b. circa 1697-1712; d. circa 1762- 1774), a free black Jamaican “whose education was sponsored by the second Duke of Montagu as an experiment to prove the educability of people of African descent.”

This work—“Carmen, or, An Ode”—was published by Edward Long in A History of Jamaica (1774), with critical notes in English, to “discredit the literary ability of Jamaica’s most educated free black”; Long believed in the slave system; this would prove the inferiority of Africans. But the publication had the opposite effect. Long’s translation proved Williams’s technical skill as a poet. The ode was written as a welcome to the new brigadier general and governor of Jamaica. He was a Scot and not popular with the English planters in Jamaica.

Williams was the son of free Negroes. A lively boy, he became the subject of an experiment by the Duke of Montagu to see whether “a Negroe might not be found as capable of literature as a white person.” He was sent to a grammar school in England, then placed in Cambridge University, where he made progress in mathematics. On his return to Jamaica, the duke attempted to set him up as one of the governor’s council, to try his genius in active politics; but the plan faded because of the objections of the governor, Mr. Trelawny, so Williams set up a school in Spanish Town where he taught reading, writing, Latin, and elementary mathematics.

Then there is Frances Seymour’s “The Story of Inkle and Yarico,” first published in 1726 and in 1738, together with “An Epistle from Yarico to Inkle, After he had left her in Slavery.” Seymour was a well-known literary figure in London. Born Frances Thynne, she married Algernon Seymour, Earl of Hertford, who became the seventh duke of Somerset in 1748. The tale, told in unadorned, interminable couplets, describes how a youth, shipwrecked and avoiding the fate of his shipmates who are eaten by cannibals,

…reflects on his companions fate,

His threat’ning danger, and abandon’d state.

Whilst thus in fruitless grief he spent the day,

A Negro Virgin chanc’d to pass that way;

He view’d her naked beauties with surprise,

Her well proportion’d limbs and sprightly eyes!

Boing! The anachronistic, animated cartoon is off! The eyes goggle and spring from their sockets at the bounce of the virginal backside. The Negro virgin is equally entranced. She hides him in a vaulted rock, brings him fruit, and fills his thirst from a “chrystal fountain.” They form a language in which they might converse and declare their love; she spreads his bed with speckled tiger skins (whence, prithee?) and bird plumes (can’t you just see the crib?). Like Odysseus and Calypso, Inkle is getting itchy for home, but he promises

“Oh could I but, my Yarico, with thee

Once more my dear, my native country see!

In softest silks thy limbs should be array’d,

Like that of which the cloaths I wear are made…”

Well, you can predict the rest of this iambic pentametrical rap, right? You know what the ungrateful white calculating swain’s going to do, don’t you? One day the Virgin (which is what she was, that is) sees a European vessel and signals it to come ashore. She tells Inkle and the two of them go down to the beach and he finds that the crew are his countrymen and friends. But here’s what the thankless sonofabitch Inkle is thinking, with emphasis too:

“Was it for this, said he, I cross’d the Main

Only a doating Virgin’s heart to gain?“

Only! Inkle, you dog, and that’s not how to spell “doting,” but don’t let me interrupt.

“I needed not for such a prize to roam,

There are a thousand doating maids at home.”

Inkle! Inkle! After the juicy mangoes and the crystal streams, diet and regular, after the tiger-skin crib and the you-know-what of these coupling couplets, that’s the best you can do? More, because he sells Yarico into slavery. Besides, she’s pregnant. But without a tear’s twinkle, Inkle gets aboard the ship and leaves her there. The first tourist. Cf. “Jamaica Farewell” by H. Belafonte.

Yarico writes Inkle an epistle “After he had left her in Slavery,” claiming:

And, spite of thy barbarity to me,

My faithful Soul for ever doats on thee,

which shows in “doats” that in addition to abandoning her, Inkle taught her this old-fashioned spelling. Inkle sets mother and child into slavery, but Yarico is consoled by a “hoary Christian Priest” who tells her that

Beyond the azure skies

And silver moon another region lies;

And there in chrystal palaces or bowers,

Deck’d with eternal greens and fragrant flowers

Yarico will find happiness. As for that Inkle, he’ll sink the way he deserves, where sinners

must never taste celestial joy;

But underneath the earth to pits retire,

Where they will burn in everlasting fire.

2.

The anthology carries the complete text of James Grainger’s The Sugar Cane, published in 1764, one of the most ambitious and well-received poems to be written in the British colonies in America before the Revolution, and which, according to Krise’s introduction, inspired Samuel Johnson to write in the Critical Review of October 1764: “We have been destitute till now of an American poet, that could bear any degree of competition.” Grainger, a doctor, a Scotsman, was a translator of Tibullus and a friend of Oliver Goldsmith, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and William Shenstone as well as Dr. Johnson. In 1759, to improve his fortune, he moved to St. Kitts as the paid companion to John Bourryau, a wealthy plantation owner. Boswell writes that the manuscript of The Sugar Cane was read at Sir Joshua Reynolds’s house, “where the company,” Krise’s introduction says, “was amused by Grainger’s account of the ravages caused in sugar cane fields by rats.” Perhaps by this passage especially, a formula for rat poison:

With Misnian arsenic, deleterious bane,

Pound up the ripe cassada’s well-rasp’d root,

And form in pellets; these profusely spread

Round the Cane-groves, where sculk the vermin-breed:

They, greedy, and unweeting of the bait,

Crowd to the inviting cates, and swift devour

Their palatable Death; for soon they seek

The neighbouring spring; and drink, and swell, and die.

Apart from all those bloated carcasses of “the vermin-breed,” meaning heaps of dead rats, the poem, which is very long and in four books, has a healthy determined sweep to it. We can imagine the gust of inspiration that came with vistas of emerald grasses in full season, their oceanic sound and their feathery arrows bending, with the stack of the factory chimney and the slowly spinning vanes of a windmill, the hazed sea beyond the beach and the sweet smell of the hot canes mixed with the smell of the sea, sugar, and salt, and a joy of sudden inspiration that lifted like a sea bird over the big mountain urging the Scottish doctor to do for St. Kitts’s cane what the Mantuan did for wheat: his own Georgics!

Tho’ lofty Maro (whose immortal Muse

Distant I follow, and, submiss, adore)

with some Miltonic borrowings (“Where were ye nymphs, when the remorseless deep/Closed o’er the head of our young Lycidas?”):

Where were ye, watches, when the flame burst forth?

A little care had then the hydra quell’d.

Reading every footnote, crawling and halting like a mite at the obstacle of every date, you burrow through the stalks of Grainger’s poem, in four books, with a false sense of scholarship, archival as a silverfish, thorough as a caterpillar, ending it in a triumph of exhaustion, since not only the poem itself but a buttressing subtext tells us everything we need to know:

What soil the Cane affects: what care demands;

Beneath what signs to plant; what ills await;

How the hot nectar best to christallize;

And Africa’s sable progeny to treat.

This is its diction, elevated enough to make a cane-cutter Othello. Its Augustan sweep surveys Nevis with Dr. Johnson’s injunction to survey mankind from China to Peru, but Grainger’s canes are a subject, encyclopedic in his observation of them, yet without the oceanic rustle, smell, and freshness of real fields. Their muse is Geography as History.

But History has no reality until it turns to fiction, until it invents and describes conversation, locale, character and its contradictions. Samuel Selvon, the Trinidadian novelist and short-story writer of East Indian descent, titled one of his stories “Cane Is Bitter.” Bitter because it soured the hopes of his indentured servants who worked the cane estates for murderous hours in infernal heat, chopping the stalks, piling them on narrow-gauge wagons that trundled them to the factory, threatened with snakebites and bites from “the vermin-breed.” Most of the Antilles have substituted bananas for sugar cane, but Trinidad still grows cane, and the cane-burning that precedes its harvest as well as infinite acres of the cane in arrow are beautiful enough to stir the heart of a Grainger and the ironic praise of a Selvon.

These documents, involuntarily and deliberately, serve another notice. They are historical, archival, but they are also redemptions from illegitimacy. Their discovery confirms the claim of the enslaved to a certain right, the continuity of History, the privilege of a record of illumination instead of the black hole of ignorance, of an enforced amnesia, of the nothingness that used to be Caribbean history. The joy of their discovery is almost evangelical. Certainly it is European in the same way that a massacre or a famine in the Middle Ages becomes history and literature, in the same way that the Holocaust has become a part of European history and literature. There is such pride in print! Where there was this black hole, a light, however thin, is shed by this selection of literature and history from which old forms, poem and essay, are made traditional and stable, and, however masochistically, a heritage.

These shapes are spectral but are part of what is claimed as a common past where the old ignorance, the helpless amnesia, was more sacred. All the more irritating, maybe even insulting, because the contributions are so mediocre, so feeble, that to appropriate them as the sources of a West Indian literature has the plaintive claim of a grateful bastard. Better the thick-headed ignorance of an illiterate slave or coolie than these watery rhapsodies over cane fields and bamboo groves. For example: A General Description of the West-Indians Islands by John Singleton (1760s). Influenced by Grainger, Singleton wrote his own topographical blank-verse poem describing his travels through the Leeward and Windward Islands. He was a member of Lewis Hallam’s professional acting company who toured the North American colonies, Jamaica, and the eastern Caribbean islands.

Singleton acknowledges his debt to the interminable Grainger—

…nor let my languid pen

Disgrace those climes, which late thy fav’rite son,

Thy tuneful Grainger, nurs’d in Fancy’s arms,

So elegantly sung…

—with such instructive gems as:

…Know then, ye fair,

Among your plagues I count the negro race,

Savage by nature. Art essays in vain

To mend their tempers, or to tune their souls

In unison with ours.

The proof of which is in the fact that after pages of this turgid mechanical meter, my soul was out of tune and unison with his, since my head felt as if it were being repeatedly clubbed by bolsters, proving that too much pentameter can deafen you. I looked around the room dully, desperate for some rescue; but I groaned and resumed. On, to miscegenation:

Or does the sable miss then please you most

When from her tender delicate embrace

A frousy Fragrance all around she fumes.

3.

What, simultaneously, was going on in the Ivory and Guinea Coasts while these poems and speeches were being written? What was the tribal life in the villages along their wide rivers infested with crocodiles, their forests of screeching monkeys, what hierarchy of customs, what exchange of utterances, what systems of grief for burial, marriage, birth? Every collection of human beings gathered for a long time in one place codifies itself, arranges rules of conduct, and makes a calendar for its celebrations of harvest, of the shapes of the moon, with tribal melodies, and preserves its fables and its history in the archives of the shaman and the griot and the bard’s memory. The first printing press arrived in Jamaica in 1717. “The vast majority of West Indian literary works,” Krise states, “were printed in London.” They still are. There are no real publishing houses in the Caribbean, certainly none on a metropolitan scale.

Because of this, the vocal tradition, apart from calypso, conte, reggae, and hymn, is audible in the best West Indian fiction, which has the inflections of the storyteller and of conversational, confessional intimacy. Also, novel and short story have the formal, three-paneled design of plot, a stronger presence than print, or one that blends with print. But the rhythm of that melody is not one that continues the printed sound of this collection. It is the rhythm of the storyteller and singer. It underlines Caribbean fiction. It is there in Naipaul, in Jamaica Kincaid, in Chamoiseau.

But the story is always the storyteller’s viewpoint, including the narrative of history.

When you have finished reading Krise’s collection, an old map of the islands does not look like a cartography of imagined paradises, but like what they were in historical reality: a succession of crusted scabs with the curve of the archipelago a still-healing welt. No metaphor is too ugly for the hatred and cruelty the West Indians endured; yet their light is paradisal, their harbors and shielding hills, their flowering trees and windy savannas Edenic, and they are not so by contrast with the extermination of the original West Indians and the routines of slavery, but because they were there before the empires, not serving but ignoring their power. No historical collection acknowledges the fact that the beauty of the Caribbean islands could have helped the slave survive, whenever these intervals, like the light through rain clouds over a sea of sugar cane, or shadows moving over the Jamaican mountains, fell, and, in their serenity, exacted some strength, because what is surely another beauty is the strength, the endurance of the survivor.

Those survivors, even in their mental and physical shackles, must have muttered to themselves that the nature which they occupied was not hostile to them for any reason, that before the sun became infernal and they moved through the cane harvesting like charred, black sticks, there was some separate benediction in the stupendous dawns and sunsets that had nothing to do with the boring evil of their servitude. Out of that condition, incredibly, came humor, mockery, and self-parody, an attitude incomprehensible to those who tortured them, a tone of voice in their music which is superior to tragedy—the tragicomic. And since the tone that this anthology has is the tragical-pastoral, in the midst of that tone one begins to hear another meter, defiantly based on delight and on the drumming of slaves, a lacerating elation, a denial based on celebration. The victims of slavery never stopped dancing and singing, although four million of them died in the crossing and the seasoning, and it is that meter which matches the landscape that, at nightfall by their permitted bonfires, especially at cane harvest, cane-crop time, developed something greater than tragedy, greater than the feeble iambic couplets and turgid prose of this anthology.

What is missing will never be recognized because it is unrecordable. Besides, its language is lost. Not one of these pieces can claim to be art, but they are certainly history, and if they are virtually worthless as art, as literature, our instinct to preserve them simply because they exist is the wrong instinct. It is the instinct of the master whose sense of art, unlike that of his servant, is also historical, chronological; and this set the trap poor Francis Williams fell into as an experiment by attending Cambridge and composing a Latin ode that showed that his was as good as those of his enslavers. His shadow frequently crosses the pages of this collection, which tries to demonstrate that there is a heritage, an ancestry in West Indian literature just as there is in English literature. Immediately the paradox rises, that West Indian writers, those of African and Indian origins, are basically all Francis Williamses because we write in English, have attended Cambridge and Oxford, have our works printed in England, and, despite emancipation and delivery from indenture, we continue, much as this article does, an inescapable English tradition.

If this were not so, why afflict any reader with pages of interminable, awful verse, with scribbling from old newspapers because they are archival? What is archival in the Caribbean, as the Caribbean writer knows, is what got lost in the annals of sugar cane burned every harvest like the library of Alexandria, what disappeared in spray in the wake of the slaves. A huge amnesia rather than a history. That is our first book of Genesis. In the end, as it was in the Beginning, it is still the Word, not just the Noun or the Number, that illuminates every race.

The colonial claim to English recedes as far back as Anglo-Saxon; part of its inheritance lies in deciphering the surviving fragments of its literature, and the claim revolves on whether a West Indian should write “their” or “our” when he is writing about English fiction or poetry. Rather than politicize the crisis into one of generic or individual identity, one should accept the irony or ambiguity or even the schizoid bewilderment of the drama as an enrichening process, one that has produced great writers, like Joyce in bilingual Ireland. There are always two contradicting classes anyway—the condition of every writer is always one of choice, of high or low diction, of dialect or rhetoric at their extreme; there are always two histories, the interior history of the writer and that of the established order of Academy, Church, or Government.

That was the afflicting torment of successful colonials, that the deeper our education the more it moved us away from the people. As it divided, though, so it enriched. A whole literature was made of this division, in theater, in music, and even in painting; but this is true of all the faded map of the vastest empire known to history. All its protectorates, dominions, and colonies, in other European languages as well, have had demeaning annals, banal poetry, and picaresque writing. It is when they can be shrugged off as negligible, as these documents in Caribbeana ultimately are, that we can wake into a clear dream of the present, after that history which Joyce, a great poet from a bilingual culture, called a nightmare.

This Issue

June 15, 2000