In response to:

Put Out More Flags from the May 20, 1999 issue

To the Editors:

People hate a man who complains, and who would want that? Nevertheless, it is a matter of some concern to me that my amicably inaccurate portrait drawn by Ian Buruma in his Anglomania has been further distorted by the vague recollections of Neal Ascherson [“Put Out More Flags,” NYR, May 20]. I was not aware twenty years ago when he gallantly stood me a cup of coffee that it was payment for my conversation, a price he seems to begrudge me even now. Well, he’s a Scot of sorts. As a former party leader, parliamentarian, and author, I am used to overly imaginative flights of fancy about myself, but Hungarian readers can compare them to my writings and public utterances, and your readers cannot. Apart from a few scattered essays I have written in English, my books are foreign: Graeca sunt, non leguntur.

And this brings me to a more general point: East Europeans do not seem to be a source of knowledge about themselves. What the Anglo-American “quality press” wants from us is testimony, an unreflective, straightforward chronicle of our troubles. Interpretation, analysis is for grown-ups (cf. my “Victory Defeated,” Journal of Democracy, January 1999, pp. 63-68). This is why the natives who dare to think for themselves, such as myself or the Slovene philosopher and psychoanalyst Slavoj Zizek, get the condescending tags of “maverick,” “flamboyant,” “eccentric,” and the like, a customary move to marginalize your rival. One of these clichés is the strategic placing of such people in a café. I am sorry to point out to a distinguished reporter of Mr. Ascherson’s eminence, who is presumably conversant with the facts of East European life, that there is not one single café in Budapest, let alone Kolozsvár or Bucharest (if he wants to be immersed in the study of the profound distinctions between a café, a bar, and a restaurant, I would recommend Georges Simenon’s “The Most Obstinate Customer in the World,” in his Maigret’s Christmas, translated by Jean Stewart, Harcourt Brace, 1976, pp. 157-186). Another such move is to ex-territorialize the cumbersome native: he must be an émigré, an exile; as a matter of fact, I never moved to England, which I have the effrontery to merely visit.

Although I am not a conservative any longer, I still think that Mr. Ascherson’s description of The Spectator in the 1980s is grossly exaggerated. I grew up as a half-Jewish ethnic Hungarian in Transylvania and, believe me, I am rather sensitive to xenophobia and suchlike. Or does anybody seriously think that the three successive foreign editors of The Spectator, Timothy Garton Ash, Noel Malcolm, Ian Buruma, or its chief book reviewer, Anita Brookner, do belong to the “Yoicks! Hark forrard!” crowd? What that weekly has become since Charles Moore’s departure—that’s a different kettle of fish altogether.

I cannot pretend that Iknow the social intricacies of the perfidious Albion inside out, but I can make an educated guess as to why British gentlemen who are not rooted in l’Angleterre profonde would foist their own forlorn love affair with England or Scotland onto an innocent foreigner who prefers France anyway.*

G.M. Tamás

Budapest, Hungary

Neal Ascherson replies:

I stand convicted of buying a thimbleful of coffee for Professor G.M. Tamás in a what-d’you-call-it—maybe a coffeehouse?—and I probably even repeated the offense in other such places. I also now appreciate how hard Professor Tamás still finds that to forgive, in his own surprisingly Scottish way (I remember one Scottish poet being lent three shillings and sixpence by a colleague and hating him for it until the day he died). The point is, though, that the coffee was not an inducement but a fuel. Anyway, what I heard from G.M. Tamás was precisely the flow of knowledge not only about the outside world but about East Europeans which he thinks Anglo-Americans do not want to hear. I met him in order to be educated, and came away well entertained and wiser.

I can also imagine that he would have had much less difficulty in seizing aspects of Englishness than most English people. But he seems to have gone off the place again, rather like Buruma’s Anglomanes and to some extent Ian Buruma himself. What went wrong? The “Lettres Anglaises” of Gaspar Miklos Tamás would be a book worth reading, even over a cup of weak tea in a London café.

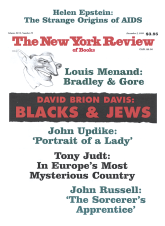

This Issue

December 2, 1999

-

*

If anybody cares to find out what a dissident intellectual thinks of dissident intellectuals, see G.M. Tamás, “The Legacy of Dissent” [originally printed in the TLS, May 14, 1993], in The Revolutions of 1989 (Routledge, 1999), pp. 181-197.

↩