We had the problem of age, the problem of wishing to linger.

Not needing, anymore, even to make a contribution.

Merely wishing to linger: to be, to be here.

And to stare at things, but with no real avidity.

To browse, to purchase nothing.

But there were many of us; we took up time. We crowded out

our own children, and the children of friends. We did great damage,

meaning no harm.

We continued to plan; to fix things as they broke.

To repair, to improve. We traveled, we put in gardens.

And we continued brazenly to plant trees and perennials.

We asked so little of the world. We understood

the offense of advice, of holding forth. We checked ourselves:

we were correct, we were silent.

But we could not cure ourselves of desire, not completely.

Our hands, folded, reeked of it.

How did we do so much damage, merely sitting and watching,

strolling, on fine days, the grounds of the parks, the arboretum,

or sitting on benches in front of the public library,

feeding pigeons out of a paper bag?

We were correct, and yet desire pursued us.

Like a great force, a god. And the young

were offended; their hearts

turned cold in reaction. We asked

so little of the world; small things seemed to us

immense wealth. Merely to smell once more the early roses

in the arboretum: we asked

so little, and we claimed nothing. And the young

withered nevertheless.

Or they become like stones in the arboretum: as though

our continued existence, our asking so little for so many years, meant

we asked everything.

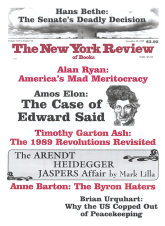

This Issue

November 18, 1999