This is an interview given by Isaiah Berlin on April 12, 1965, in Washington, D.C., to Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., for the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library in Boston. It has been edited and shortened with the help of Henry Hardy, Berlin’s editor and one of his literary trustees. A recording and full transcript of the interview are held by the library.

—The Editors

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.: When did you first meet President Kennedy?

Isaiah Berlin: I met President Kennedy at dinner with Joe Alsop. Joe Alsop is one of my oldest friends and he telephoned me when I was at Harvard in autumn 1962. He asked me to dinner in honor of Charles Bohlen, who was just leaving to be the United States ambassador in Paris. And at this dinner President Kennedy was going to be present.

I remember the slight stiffness of atmosphere, which always occurs when royalty attends. People are keyed up to meet them, and, at the same time, there is always an air of slight embarrassment. Kennedy went round the circle, shook hands with everybody, and we sat down to dinner. He was very amiable. He was in a jolly mood, which was very remarkable, considering that that was the morning on which he had been shown the photographs of the Soviet installations on Cuba. And I must say the sang-froid which he displayed, and the extraordinary capacity for self-control, on a day on which he must have been intensely preoccupied, was one of the most astonishing exhibitions of self-restraint and strength of will that I think I’ve ever seen.

A certain amount of chaff occurred across the table. Nothing serious was said. Present also were, I think, the French Ambassador and Madame Hervé Alphand, and one or two other people. A small dinner. Then, I remember, when the men were left alone, I was put next to the President. It was obvious that I was represented to him as a kind of Soviet expert, which I’m very far from being. He asked me a number of questions about Russia, which I didn’t answer particularly well. I felt I hadn’t really done very well.

A.S.: What sort of questions were these?

I.B.: About why the Russians were not making more trouble in Berlin than they were at that particular moment; what the Russian motive was for various of their acts. He listened with extreme intentness. This was one of the things which struck me most forcibly. I’ve never known a man who listened to every single word that one uttered more attentively. His eyes protruded slightly, he leant forward toward one, and one was made to feel nervous and responsible by the fact that obviously every word registered. And he replied always very relevantly. He didn’t obviously have ideas in his own mind which he wanted to expound, or for which he simply used one’s own talk as an occasion, as a sort of launching pad. He really listened to what one said and answered that. The only other person I had ever heard of who displayed a similar kind of attentiveness was Lenin, who used to exhaust people simply by listening to them—a particular kind of riveted attention.

Kennedy talked about Stalin and what people round the table supposed were Stalin’s fundamental motives; what differences there were between Stalin and Khrushchev; what Russian intentions were. From time to time he said things which puzzled me, and still puzzle me, for example: “Someone ought to write a book on Stalin’s philosophy.”

Well, he knew that I was a professor of this subject, more or less, and I suppose he thought this was the thing to say. I said, “In what sense do you mean ‘philosophy’?” He explained that every great political leader must have some kind of theoretical structure to his thought, and he had no doubt that Stalin had a most fascinating and important set of principles which he followed. This I rather doubted, but I don’t think I expressed my doubts very forcibly on this occasion.

A.S.: Did you get much of a sense of his own conception of Soviet society? For example, Chip [Charles Bohlen] believes that President Kennedy had an inadequate appreciation of the role of ideology in the Soviet Union, and tended to see it too much in practical terms.

I.B.: I think that was so. But I think this business about Stalin’s philosophy must have been a concession in the other direction. The thing which struck me about him then, and later, was that he was on the job all the time. I don’t know how much interest he really had in fields of study for their own sake, I mean in history or in politics, in government, that kind of thing; but it seemed to me that he was absolutely intent on what he was doing, and asked questions, listened to answers, read books, conveyed impressions which were directly geared to the conduct of his own particular office; that he was determined to use and concentrate everything that came his way toward actual practical realization, not specially of any given policy in the short run, but of some coherent, general attitude to life, to policy, so that everything was grist to a mill.

Advertisement

I don’t think he allowed himself to be distracted very much, at least as far as intellectual topics were concerned, by idle curiosity roaming here and there. And he was riveted by the thought of great men. There was no doubt that when he talked about Churchill, whom he obviously admired vastly, when he talked about Stalin, when he talked about Napoleon, Lenin—every time he talked about one of these world leaders, his eyes shone with a particular glitter, and it was quite clear that he thought in terms of great men and what they were able to do, not at all of impersonal forces. A very, very personalized view of history, as you might say.

A.S.: Roosevelt, was he mentioned?

I.B.: No. Roosevelt wasn’t mentioned on this occasion. No. I’m trying to think what was mentioned. Bismarck he mentioned. Him he asked questions about.

A.S.: He had a great admiration for Bismarck. I never heard him mention Napoleon.

I.B.: Napoleon came up, I think, in the course of some comparison with Stalin or Lenin. I remember that on a later occasion I told him a rather frivolous story about Lenin’s personal life; about the fact that somebody had published a piece on a personal affair of Lenin’s, some kind of curious, still uninvestigated connection that Lenin had with a lady somewhere in 1911, 1912. He was very displeased. He thought this was not at all the way to treat a great man. I felt that he thought this was in some way debunking, or anyhow a contemptuous attitude towards a man who ought to be treated with a greater degree of solemnity, at least by me, and at least in his presence.

I dare say with more intimate persons he would have gossiped happily about this subject. But in this particular case I had a feeling that he thought one mustn’t talk about the private affairs of great heads of states in quite that tone of voice. I felt put in my place. I went on and on too. I had one of those compulsive moments in which I realized my story wasn’t going down very well. There was a total silence. And I carried on in the most reckless fashion till I finished. He didn’t snub me in any way. He frowned. We changed the subject.

A.S.: On this first night, in retrospect, did any of his questions bear upon what was happening in Cuba?

I.B.: Yes, to the extent that he couldn’t understand, given that there was a generally disturbed situation then, why the Russians didn’t make more trouble in Berlin, in order to make general trouble for the United States. Various hypotheses were then advanced by Bohlen, by Phil Graham, by Joe Alsop, by myself, and this was generally discussed round the table. But the point about him was that he gave one the air of luminous intelligence and extreme rationality, and cutting through a lot of dead wood. He didn’t accept loose or vague statements, or the kind of general statements which people make who haven’t very much to say but feel they ought to make some contribution to the conversation, simply as a form of registering the fact that they are present and have views.

Whenever that kind of statement was made by any of us, he stopped us short and asked us exactly what these words meant, and brought it all down to extremely clear and shining brass tacks. In all these cases he was very good. As a cross-examiner he was absolutely superb: no doubt about that. But I had the impression of an extremely concentrated figure, very uneasy to talk to, not at all cozy, not at all comfortable; on the contrary, self-conscious and no doubt, on that evening, worried; in general, withdrawn rather than outgoing, in spite of all the jokes and the jollity during dinner and afterward, and his iron self-control. There was an enormous sense of unsureness of some sort, maybe simply because he felt among intellectuals, or something of that kind, and he wasn’t quite sure what he ought to talk about, or what he was expected to do. A curious lack of self-confidence on the part of the President of the United States.

Advertisement

He wasn’t at all easily dominant. He was like a very important person, a frightfully important young man, who was in charge of enormous things, constantly leaping over hurdles. I had a sense—I may be wrong about this—that except at times when he really relaxed, no doubt among his intimates and people he knew well, he thought of life as a series of hurdles, resistances, which had to be overcome, and therefore screwed himself up to it each time; and that he didn’t do it in a sort of easy, jaunty fashion, which obviously Roosevelt must have done, or with the natural sense of public life as his proper element which Churchill had. I think he had to screw himself up each time and expend nervous energy upon obstacle after obstacle, hurdle after hurdle. It was a hard thing.

A.S.: Did anything surprise you about him that night? I mean anything that was different from what expectations you might have had?

I.B.: Yes. I think I must have conceived of him as being rather more ordinary in a certain sense. Rather like a sort of amiable, gay, successful, ambitious young Irish-American, with a great deal of blarney. Not at all. He was serious and glowed with a kind of electric energy; and a rather inspiring figure to work for—that I could perceive. And there was this mysterious charismatic quality, certainly. I could see that he was driving somewhere, and people who liked that sort of thing would be delighted to follow him, to be driven by him, to cooperate with him. He was a natural leader, and absolutely serious, absolutely intent. There was something deeply concentrated and directed, fully under control. If ever there was a man who directed his own life in a conscious way, it was he—it seemed to me he didn’t drift or float in any respect at all. Some kind of embodied will, you felt. This was really very impressive.

I met Mr. Churchill late in life, and he was by this time a famous sacred monster, and therefore behaved in acordance with what must have become a kind of second nature. He behaved exactly like a person permanently on a stage, saying those mar- velous things in a splendid voice and delighting the company, but they weren’t the natural utterances of a normal human being. They were the grand utterances of somebody on a great historic stage. Whereas with Kennedy you felt that it cost him some effort, but that probably the Emperor Augustus was rather like that, who had suddenly inherited an enormous empire, was frightfully serious, perhaps rather ruthless, but determined to carry the whole enormous load, to carry the whole thing to an enormous success, cost what it might. This, anyway, was terrifying but rather marvelous. Oh, I was deeply impressed; I really was. Frightened, rather, but impressed.

A.S.: When was the next meeting?

I.B.: The next meeting was in the White House. Well, you remember that. Nothing very significant occurred on that occasion. The atmosphere was much easier. This, of course, was after Cuba No. 2 had occurred, and he was in a glow of absolute happiness. He said, more or less, that he thought that Cuba No. 1 would remain as a stain upon his reputation, no matter what he achieved later, no matter how glorious and splendid his presidency would be. There would always be this fearful stigma, which historians would always note. I then felt that he really was thinking about history: not so much his reputation in a small sense, as a personal reputation, but the figure he would cut in history and his particular relationship to other historic figures. He saw a panorama. There is no doubt it was all very self-conscious, in that sense. He was unspontaneous to the highest degree. This is, I think, what made conversation with him—for strangers, at least—a little difficult. Interesting, but difficult.

He obviously, quite naturally, was in a state of triumph and satisfaction after the second Cuba crisis, and again talked about the Russians, but this time in a much more relaxed fashion. He wondered what he was going to do; he wondered how he would now get on with Khrushchev; he wondered if this humiliation cost Khrushchev too much; he wondered if something ought to be done to save his face and what, if so, he could do.

He talked about British statesmen on this occasion. He said that he liked Macmillan very much. He got on very well with him. Although he found him difficult in some respects he found his company delightful and his wit unexpected. But the person he really liked was Hugh Gaitskell. He said he liked them both and couldn’t understand why they detested each other. I tried to furnish some explanation in political terms, but he rightly brushed this aside and said that he thought that the hostility was beyond the call of ordinary political duty, which I am sure is true.

Gaitskell said about him to me that he thought he was a wholly rational man; what was so admirable about him was that he was moved by rational motives. By contrast with Eisenhower, whom he regarded as moved by emotional prejudice to a high degree, he regarded President Kennedy as a man whose motives were intelligible and with whom one could, so to speak, do business at the highest level. One could do business with a highly mature figure who understood exactly what one said, without having to adjust one’s words or one’s thoughts to somebody obsessed by some particular pattern of emotion, or some particular outlook to which one would have to fit oneself in some particular way. I could see that Gaitskell liked him very, very much indeed, and really was delighted by his meeting.

This was, as is so often the case, reciprocated. Kennedy talked about Gaitskell in very warm terms, but wondered why he was being so intolerable about Europe. It struck him that Gaitskell was highly unreasonable about not wishing to enter Europe.1 He knew that the Labour Party was divided on this issue, and he understood the political motives which might have made Gaitskell careful in this respect. But he could not persuade himself that Gaitskell didn’t see absolutely clearly that entrance into Europe was right. In fact he was convinced that when Gaitskell put up objections to entering Europe, he wasn’t wholly sincere; or at any rate was acting politically and would presently do something else, alter his course.

He hoped he would, and asked me whether I thought that he would. I can’t remember what I answered. I think I agreed with him. I think I thought that Gaitskell was fundamentally pro-European, even though he might object to this or that aspect of the particular terms on which England had been asked to come in, and didn’t think it a short-term proposition. But he kept on harking back to this problem.

A.S.: That evening came about because Jackie called me and said that, now that the missile crisis was over, we should have an evening of gaiety to relax the President, and suggested getting hold of you, and I suggested getting hold of Sam Behrman.

I.B.: There was no gaiety on that occasion, and I didn’t think, on the whole, that this particular company would conduce to gaiety, as far as he was concerned. He was only gay, if he was going to be gay, in relaxed company of some sort. No, he talked about politics to me on that evening as well, certainly. Mrs. Kennedy came in after having looked, if you remember, through some kind of glass partition at a meeting of the National Security Council at which Adlai Stevenson must have been present.2 She conveyed the fact that he was speaking with the most fearful indignation about the treatment which had been meted out to him in a then fairly recent article, I think, published in the Saturday Evening Post by Stewart Alsop and Charles Bartlett.

A.S.: I think that was later.

I.B.: Well, I think the point was that he had been accused of weakness on Cuba. Wasn’t that in the article?

A.S.: That was in the article. I think the article came out in December. I think this was in November.

I.B.: Well, then, something else must have come out—a column, perhaps.

A.S.: Yes, probably.

I.B.: At any rate, Stevenson was accused of softness about Cuba and felt that the White House had not supported him sufficiently in this respect, and hadn’t exonerated him from this fearful charge, or hadn’t made out, anyhow, that he’d behaved in a manner for which he thought he ought to have been, if not actually congratulated, at any rate respected more than he turned out to be. He was obviously in a rather indignant mood [in the NSC meeting]; and the President did make one or two ironical remarks about that. That I clearly recollect.

Later the President left, but so long as he was there, tension prevailed. There’s no doubt about that—a rather exciting tension, but tension nevertheless. I think perhaps I felt it more strongly than my wife did, who found him very amiable, and quite easy to talk to. But every time he turned to me, I felt I was a little bit under examination—being, not grilled, but cross-examined about subjects about which I was conceived to know. I had a feeling, although I may be wrong, that he always, with strangers at least, docketed and labeled them as being experts on this or that, likely to provide interesting or important or at any rate stimulating information about this or that subject, and wished in some way to exploit them—I mean in the best sense of the word—to make use of them intellectually, at least, to the highest advantage, not just to let the conversation dribble in some undirected fashion.

I had the general feeling, also, that he looked round the world in this sort of way. It was a kind of orange to be squeezed. There were a lot of facts in the world, and a lot of persons, and a lot of events. The great thing was not to allow oneself to drift along, or to allow oneself, even, to be passive in the face of them. One hadn’t many years to live, and one must do what one can with what one has. One must make use of everything, and direct everything.

I don’t think his ambition was to leave his own impress upon life. The idea was to act, to act, always act; never relax, always act, strive for something, try for something, build something, make something, fail, try again. Endless drive, endless remorseless forward movement, which may come from his palace education. At least people said so.

On this particular occasion, I think, his brother, the attorney general, was present. The rapport between the brothers was absolutely astonishing. Whenever either spoke to the other, the understanding was complete, they agreed with each other, they smiled at each other, they laughed at each other’s jokes, and they behaved as if nobody else was present. One suddenly felt there was this absolutely unique rapport, such as is very uncommon, even among relations. They hardly had to speak to each other. They understood each other from a half word. There was a kind of constant, almost telepathic, contact between them.

Always, always there was this atmosphere of high tension, and a sense that Kennedy wanted to get things done on the basis of the best factual evidence, the best intellectual judgment available. He didn’t believe in off-the-cuff conduct at all. I felt he was a tremendous non-improviser, that everything cost him a lot of effort, that he really did expend a lot of himself. I may be quite wrong about this, this may be just a subjective impression, but he didn’t seem to do anything with ease, facility, panache, a sense of throwing it off, in the sense in which Roosevelt did.

I had the general impression, also, when I met him, that he switched from gear to gear. Either he was talking seriously, in which case his whole attention was concentrated and directed upon what he was talking about. Any book he might have read, any article he might have read, any conversation he might have had, any personal impression he might have sustained—all this was brought together and brought to bear upon the subject in question, and he asked these very penetrating and drilling questions.

Either that, or he decided not to do this, in which case he leant back and behaved in the kind of jolly fashion of any rich young man enjoying himself in a highly convivial, ordinary, conventional, quite easy, quite agreeable manner. Nothing in between. About that you would know more than I would. Perhaps this is oversimplified.

A.S.: I think that with people whom he knew very, very well, there was much more of a quick change of tone back and forth than on formal occasions.

You’ve mentioned a sense you had that Kennedy felt that his time was short. Is this retrospective? Or did you feel that at the time?

I.B.: He didn’t say it in so many words, but I think I felt it at the time, yes.

I used to ask him questions about Europe. I did ask him about defense matters—whether he really believed that the British ought to contribute more to conventional weapons in Germany, that kind of thing. Whenever he gave his answers, he kept on saying, “Something is bound to happen. The Russians will not sit still. There’ll be great cataclysms—I don’t believe that I’m going to have a quiet term of office,” and so forth. Rather like a man who certainly didn’t anticipate, perhaps almost didn’t want, too peaceful and too uneventful a reign. I had the sense of a kind of quiet, slightly suppressed dramatization, which nevertheless went on in his mind, of almost everything. I don’t know what you felt.

A.S.: Well, I think he would have been terribly disappointed to have presided over a tranquil time in the life of the world. I think he also had a great sense of the amount of violence under the membrane of civilization.

I.B.: When he talked about foreign policy, my impression was that he thought he was a duelist, with Khrushchev at the other end. There was a tremendous world duel carried on by these two gigantic figures. Enormous rapier thrusts, tremendous technique was going on, and he was always on a qui vive of some sort, and this is what kept him going, and this is what excited him. And he had a worthy opponent. Ever since Vienna, I think, he had a sense of being pitted against Dr. Moriarty at the other end somewhere. He was the man who was going to rescue civilization; and Khrushchev was the man who was going to shoot it down, unless he could teach him a lesson, unless he could show him that these methods didn’t work, in which case some kind of uneasy but nevertheless perhaps semipermanent truce could be developed. But he felt that the whole weight of what he conceived of as the ideals of Western culture was resting on his shoulders, and this somehow excited him.

A.S.: There was a considerable change in the British conception of Kennedy, wasn’t there, after he died?

I.B.: He was very much admired, and not only admired, but regarded as an exciting figure, a sort of young paladin. He was a hero to the left, not to the right. The right was suspicious and thought he was just a vigorous, probably unscrupulous and rather ruthless young American out for the American interest, who would be much more difficult to work with than previous American presidents, and who would be terribly tough. People suspected him of inheriting some of the ideas of his father, who was thought to have been not very friendly, or at any rate to have sold England rather short in 1940, and there was a general suspicion of him in those circles.

I had a feeling, funnily enough, when he talked about Churchill (this has suddenly come into my mind), whom he praised in the most unreserved fashion, and whom he regarded as the greatest man he ever met—that’s what he said, at any rate—that his father’s performance really had determined his thoughts in certain respects. That is to say, I have a hypothesis which I wish to utter—but for this I really have no concrete evidence. Obviously he didn’t judge his father as the English judged him. He didn’t just think that he was rather feeble in the face of Hitler, or class-conscious to a degree which made him more sympathetic to the forces of the right, even in their Fascist forms, than to any forces of progress on the left, which is what people suspected him of in England, of course, certainly in 1940-1941, whether fairly or unfairly.

His father was very unpopular in England; he didn’t have much of a career when he came back to the United States, and this was obviously a crack and a crisis in his career which must have affected the rest of the family. His father, I think, must have taken the line with him that it was all right to resist Hitler effectively, but that once Chamberlain had done the things which he had done, and once no real rearmament had occurred and appeasement was in full swing, by 1939 it was too late; that Munich was a correct move, that the guarantee to Poland was absurd, and that, in fact, the Germans would win the war, and there was no reason why the United States should pull English chestnuts out of the fire and be involved in a war themselves. I mean, he simply thought that England misplayed its cards; and this made it impossible for the United States to act as an effective ally, at least from the point of view of its own national interest. Something which is at any rate more palatable than the sort of picture of Joseph Kennedy which was held in England at that time, which was just of a reactionary and cowardly anglophobe.

If President Kennedy believed all these things, then I think what must have eaten into his soul was the notion that one must never appease; that if one begins by appeasing, one always ends up in some kind of humiliating and terrible position. This, of course, probably emerged in his book, which I didn’t read. At any rate, I think he rationalized the position of his father as somebody who, perhaps mistakenly, diagnosed the position of England as hopeless when it was nearly hopeless. And therefore his particular thought took the form of saying that this must never occur to any great country again, that as soon as the faintest little danger appeared in the sky, as soon as a cloud which was no bigger than your hand appeared, immediate steps must be taken, because once one allows oneself to drift along some kind of comfortable path of compromise and appeasement, one will end up in some hideously dangerous and, indeed, humiliating position.

This determined his whole attitude to politics, his whole attitude to Russia, for example. I mean, he was prepared to be reasonable; he was prepared to use judgment; he was prepared not to allow his passions to dominate him; but he felt that resistance must be offered at once. At no point must one allow the enemy to get away with it; otherwise the terrible 1939 situation would come upon us again.

This he had in common with people like Eden, with people like Lord Salisbury, with people like Macmillan, whose entire political outlook after the war was certainly shaped and determined by their violent opposition to Chamberlain and to Munich, and by the fact that this was certainly the worst moral crisis which England passed through in their time, in which the decision which had been taken by the government was plainly morally wrong and politically disastrous. I think he was with them, so to speak. I think his sympathies lay with the anti-appeasers of the late 1930s, an attitude which he applied to the world situation in the 1960s.

A.S.: Though I think it was tempered in the case of Kennedy and Macmillan by a great sense of the horror of nuclear war. I know Kennedy would distinguish very sharply between Berlin on the one hand and Laos on the other, as to where you hold the line. Kennedy never felt that Laos was worthy of the attention of great powers.

I.B.: No, I see that. But what I meant was that the anti-appeasers in England—I mean Macmillan, Eden, Salisbury, and all these people—felt that war could have been averted with a firmer policy. Not that war should have occurred sooner, which was a different line. There were people, of course, who thought that, too. There were people who thought that we should have fought, I don’t know, in 1936, if need be, when the Germans reoccupied the Rhineland, and that if they then refused to budge after due warnings were issued, perhaps a war at that stage would have been less costly but no less avoidable than later.

I think the people I speak of genuinely thought that Hitler could have been restrained from going to war, and I should have thought that was Kennedy’s view, too. Not so much that it is better to fight than to give in, which he may also have believed, as that if you are prepared to fight at a critical phase it is possible to avoid war; and that the English statesmen and that section of the public who took that line in the 1930s were absolutely right.

A.S.: How would you distinguish Kennedy from the two other great American liberal heroes of this period, Roosevelt and Stevenson?

I.B.: Roosevelt, I think, was a very different thing altogether. I think Roosevelt was a fundamentally optimistic, happy, charming man with the tremendous natural sense of ease of a person who was born in a socially superior position, and who held, at the same time, views well to the left of his environment and his class. He was, in fact, an aristocratic radical, which is a very different thing. Nothing is more attractive than the combination of old-world manners and new-world convictions, and this proved absolutely irresistible. He found that by the use of charm, and with his general optimism and bonhomie and his large and generous personality, and by jollying people along, and by general affability all round, and not thinking things out too clearly, and not being overconcerned about the precise details of policy, he managed to roll this enormous team along toward objectives which I think he did have.

Unlike people who think that he was a pure improviser and that he had no philosophy at all, I think he had a vision of the kind of world he wished to create. I think he really was in favor of curing poverty and ignorance and doing something for the underprivileged of the world. And I think this was a kind of generous aristocratic dream, rather of an English nineteenth-century sort. I dare say people like Lord John Russell probably had it in a perhaps not quite so exuberant and ebullient fashion.

But the point about Roosevelt was that he was easygoing and thought, “Let the future come; it is all grist to our mill. We’ll manage it when it comes.” I don’t think he liked laying precise plans, and I don’t think he liked distributing precise responsibilities. Therefore the whole atmosphere was easy, relaxed, optimistic, and maddening for those who liked tidiness and order, and wanted to know precisely where they were, and believed in balanced budgets and exact formulations. That is what gave him the reputation of being not altogether a man of honor, capable of letting people down, capable, with an easy smile and a laugh, of transforming one policy into another, and not really being overscrupulous about whom he happened to drown in the process.

I think Kennedy was absolutely different from this. I think he had a concentrated intellect; he believed in technology; he believed in precise formulations; he believed in the use of the sharpest intellectual, technical resources that could possibly be assembled; and he believed in verifying and checking every step. He wasn’t at all a gay cavalryman riding over hedges and ditches, which I think is what Roosevelt in fact was, whether he saw himself in that light or not. The point about Roosevelt is that he was one of those people who liked to be amused; I think one of the things he most wanted was to be amused. It didn’t matter whom he saw, provided they delighted him, stimulated him, made him laugh. I think Kennedy very carefully distinguished between working hours and nonworking hours in that sense.

I think the people he wanted to meet and he wanted to use were people who gave him the impression of understanding the new techniques and the new situations brought about in the 1960s. He had a tremendous sense of soyons de notre temps: we ought to be men of our time; we ought to be up to and fully conversant with, abreast of, every single development—scientific, economic, political, and so forth—and therefore, although he didn’t believe in the mechanical use of experts, he had some sense of constantly going forward into unknown country which one could only enter with a maximum degree of guidance provided by imaginative and gifted experts. That’s why he was never easy.

I go back to my thesis that he wasn’t the gay cavalryman. The horse he was riding was an uncomfortable horse and he was riding it with courage and care. But care: it was unspontaneous. Every step was calculated. It seemed to me that he was, in the best sense, an extremely calculating and deliberate man; whereas Roosevelt, in the best sense, was a very uncalculating and essentially easygoing man, deeply easy-going because he trusted in his own charm; he trusted in his own power.

Above all, the point about Roosevelt was that one felt he was totally unworried, no matter how terrible the disasters. It might be Pearl Harbor, it might be some fearful economic strain upon the system, or a huge strike which it might be difficult to settle, or some frightful act of butchery committed by some enemy. No matter how terrible a thing, he slept his nine hours or whatever it was, got up on the next morning, and with great gaiety and abandon and aplomb and energy and intelligence set himself to the tasks of the next day. Whereas Kennedy tended, I think, to be pursued by grave anxieties, and his life was a much more continuous performance than these marvelous and brilliant improvisations of genius by Roosevelt.

The other thing is that Roosevelt had a much more natural rapport with the feelings and wishes of the average American voter. He really was a natural politician, I think, but Kennedy, oddly enough, was not, it seems to me—politically he was made, not born. Roosevelt had the kind of antennae that oscillated delicately in response to the slightest political breeze in any quarter and registered in his infinitely sensitive system; in this respect being different from Churchill, who, I think, didn’t oscillate at all, but imposed his own obsessive personality on other people, and didn’t get anything from them, wasn’t a function of his environment, wasn’t a seismograph in any sense.

Whereas Roosevelt was the most delicate seismograph possible—every little tremor registered. When Mrs. Roosevelt would report to him what her friends felt, and what various liberal groups or underprivileged groups in the United States wanted, and so on, he understood this perfectly. Whether he satisfied their wishes or not, he understood exactly the position they occupied in society, how many of them there were, what they wanted, what the effect of such discontent was, what the possibility was of satisfying them, at what cost, and with what effect upon certain other sections of the population. He was delighted by the mosaic itself, was delighted by the variety of life, by the fact that there were reactionaries and there were progressives, that there were bad men and there were good men, that there were stupid men and there were clever men, that there were lots of countries, all differently colored. The whole thing was not exactly a fantasy, but a splendid kaleidoscopic spectacle which he thought, and perhaps rightly, he knew almost better than anyone else how to understand and how to manage.

Kennedy, I think, was not the least like that. I think he wanted as many people as possible to believe what he believed and as many people as possible to be intelligent, progressive, aware of the findings of modern science, and rational. I may be wrong about this—I’m talking without any knowledge at all—but I should have thought he wasn’t naturally reactive to every tremor in the political atmosphere, but that this had to be reported to him. When it was reported by experts whom he trusted—not necessarily by people who took polls, but by whoever there might be whom he regarded as a careful political observer—then, putting these things together, and looking at them steadily and seeing them whole, and reflecting about them in the light of all his knowledge, he would arrive at a judgment, which might or might not be correct. Probably most often it was correct, but at any rate this was, again, an unspontaneous, deliberate process which he taught himself to enact.

This seems to me quite a different temperamental reaction from Roosevelt’s. And that is probably why Kennedy was, I think, capable of making large mistakes, which Roosevelt wouldn’t have made if his judgment had been wrong. Suppose he took wrong advice, or suppose he made a wrong judgment, as he probably did over Cuba No. 1, let us say. Roosevelt would have stopped halfway and would somehow have managed to have seventeen ways out, all of which it would have been possible for him to follow. Kennedy had to go right through with it in a rather heavy fashion and then retreat in an equally tragic and deliberate way.

In a way, this was more sympathetic. Oddly enough, in spite of his hardness and in spite of his political nature and so on, I would say that Kennedy cared more about human feelings, about distressing loyal servants who worked for the State, about dropping people who had been useful, or whom he regarded as disinterested or even noble, than Roosevelt, who cast people about and flung them in the air and let them fall into all kinds of peculiar and comical positions with the greatest possible gusto and without the slightest tremor of the heart.

Stevenson I don’t know very well, but I should have thought he is totally unlike either. I think he is a much more tremulous and scrupulous figure in some ways, who I think is perhaps even less instinctively a politician than either of the other two. I should have thought that he is a man of such sweetness of character, and concern about right and wrong, about equity and iniquitousness, and with such naturally, ethically, sensitive feelings, that caught in some ambiguous situation, as politicians are bound to be, he would on the whole tend to worry and be anxious lest what he did was in some way morally damaging, or wasn’t what was good and right and upright and proper in a given situation.

He behaved much more like an ordinary, nice person who couldn’t bear the thought of having to sacrifice worthy and virtuous persons just because the machinery of politics required it, or because some huge impersonal forces, or the wheels of history, clamored for that particular sacrifice. For that reason, I think, he was not in the least like either Roosevelt or Kennedy; he was, on the whole, too easily horrified, too easily disgusted by what is inevitably cruel and squalid in the public life of democracies.

It may seem by now perhaps a rather commonplace analogy, but there was something Bonapartist about the Kennedy reign. It wasn’t a monarchy, but neither exactly was it a republic. The origins of Mr. Joseph Kennedy, and the fact that the Kennedy family represented some kind of huge financial, commercial success, had a kind of Bonapartist flavor, whether of Napoleon I or Napoleon III. That is to say, Kennedy stood between the old aristocracy which rejected him and the left wing which to some extent distrusted him, which was precisely Napoleon’s position.

He got into power by marvelous organization of technical and intellectual means, which is exactly what Napoleon believed in. The old aristocracy of Washington, or of Boston or the South or wherever it may be, was frightfully suspicious and regarded him as obviously an adventurer and an arriviste, to some extent. But some of them were sucked into the government, nevertheless, either from personal ambition or because they were charmed and fascinated by this electric personality. They came back, very much as certain members of the French upper class nevertheless did work for Napoleon I.

Then there were these kings, the brothers, whom he appointed, or wished to appoint, to responsible positions; and his father was, as it were, the Letizia, more I think than his mother in some ways—someone in the background who had bred all these persons, and looked with delight and pride upon the extraordinary generation to which he had given rise. Then there were the marshals, who served him, the devoted, dedicated marshals who liked nothing better than to have their ears tweaked, as they were, by Napoleon. He had something, it seemed to me, of that relation to the marshals.

It was very clear who the marshals were—there were people who were marshals, and there were people who were mere generals, colonels, captains, or perhaps just faithful ministers, but who were nevertheless not quite in the position of these members of the glowing new military, technical, intellectual elite who served him. Plainly McGeorge Bundy was a marshal. I would say that Chip Bohlen had probably become a marshal by the time I arrived. Perhaps you can suggest other names. I dare say Sorensen was perhaps a marshal.

A.S.: McNamara.

I.B.: McNamara was top marshal. He was absolute père de la victoire. McNamara was in exactly the position of Carnot. Then there were people who, although they weren’t in the government, were intimates and, as it were, carried marshals’ batons in their rucksacks although they hadn’t yet the chance to use them—like Phil Graham, who I think stood rather close to the President, and who was essentially made of marshal-like material.

I’ve never met Mr. Dean Rusk, but I had the impression that he was not a marshal.

A.S.: You’re right.

I.B.: Although he had a responsible position.

A.S.: Dillon yes, Rusk no.

I.B.: Dillon was a marshal, was he? It was very clear there was an elite, there was a group of people who basked in and reflected the light of President Kennedy, people with whom he was happy, people with a great deal of energy and ambition who really were marching forward in some very exciting and romantic fashion. This really was a new phenomenon, certainly in American politics. There was nothing like it in European politics either. The nearest to a marshal we had in Europe is, I suppose, De Gaulle, in that sense. But he wasn’t really surrounded by other marshals much—a very lonely figure.

Whereas Kennedy had a sense of the team, and those who were on the team and those who were not were carefully demarcated. He was absolutely clear who was and who wasn’t. This was not so much a matter of ability or competence or even trustworthiness as a matter of responsive personal temperament, which some people had and other people didn’t. Whenever he felt that there was a kind of vigorous personal response—the word “vigorous,” of course, was much in use in Kennedy speeches and Kennedy conversation—whenever there was some kind of imagination and ambition and forward thrust—a sort of intellectual gaiety, I think, the marshals had to have.

Above all, I think, what President Kennedy hated—I may be unjust to him in this respect—was dimness. I think he liked personality; I think he liked vitality; and I think anybody who was dim, no matter how virtuous, how wise, how valuable in all kinds of ways—and a great many very noble, very saintly, very learned, and indeed very gifted people have a dim personality—was no good to him. Perhaps he was prepared to recognize such people, but they were no use to him. He somehow, I’m sure, felt that the sheen of life, the light of life, went out in their presence. Kennedy wanted not only to be stimulated but to march at the head of a small, dedicated band of men, with shining eyes. Wouldn’t you say?

A.S.: I think that’s right.

I.B.: This was a romantic concept. I don’t know where it came from: psychologically it would be most interesting to know. I suppose it was part of his education by his father, who always drove his children in an absolutely remorseless fashion, and was alleged to have said that they must always come first in everything. Being second was no good. Being second was like being a hundred and second; it didn’t count. First or nothing. There was something of that about him, and that communicated itself.

The whole Washington atmosphere was very different from what it had been when I was here during the war, although it was exciting enough then. Under President Kennedy it was terribly taut; everyone was walking some kind of tightrope and was very excited to do so. People were always terrified of slipping in some sort of way. The whole thing was stretched frightfully tight, the whole thing had a kind of dedicated and slightly desperate air, which I see would have distressed and annoyed and even depressed the sort of old radicals, the idealistic but rather loose-spun left wing, from among whom Roosevelt chose his earlier supporters. They felt the whole thing was too glittering, too much like the American Century which Mr. Luce used to support, too many men in shining armor, too heartless, too violent, too crusading, not enough humanity, not enough vagueness, not enough coziness.

A.S.: Too stylish.

I.B.: Not only too stylish, but also too driven. Knights in shining armor sitting on purebred horses, galloping in some direction, whereas what they liked was a gnarled old stick and slow cross-country progress across tufts of grass, with a lot of rather incoherent conversation of a deeply earnest and sincere kind. It’s a very different picture.

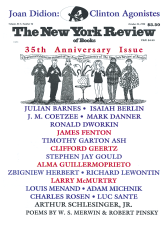

This Issue

October 22, 1998