Despite its seven Oscars I doubt that Schindler’s List will survive its season either as a memorable film or as a comment on the concentration camps, for the evil that Spielberg tries to portray lies beyond his imagination.

Hitler’s genocide was a crime against humanity, a crime in which a great part of humanity was itself an accomplice. Hitler’s victims were multitudinous, but his accomplices—both active and passive and not simply in Germany—were far more numerous. Schindler was an exotic exception and Spielberg’s film lets viewers take comfort and pride in his virtuous behavior, but the Holocaust raises terrible questions about the quality of our species, and it is these questions that Stephen Spielberg, for all his good intentions and craftsmanship, did not ask, perhaps because they did not occur to him.

His coarse and self-indulgent Nazis suggest that he has grasped the banality of evil. But he has not understood its universality, its persistence, or the magnitude of its victory in our time. This is not to say that in evil times good deeds may not be celebrated. They must be celebrated, but with some sense of historical perspective, and here Spielberg fails. He has placed the oddity Schindler in the foreground of his tale and let him determine the triumphant outcome. But Schindler’s good deed was marginal and its motivation obscure, so different from the behavior of countless others at the time and since as to suggest that he might have come from a different planet, like another famous Spielberg character.

Except to the people whose lives he saved, Schindler made no difference to the outcome of the Holocaust. But the film’s aim is to show that he made a huge difference, for he is meant (like Spencer Tracy at Black Rock, etc.) to prove that remarkable individuals can outsmart evil. What then of the others? Did they die by the millions simply because they weren’t clever enough themselves or lucky enough to find a Schindler of their own? Does the film mean to suggest that if only there had been enough Schindlers, the problem of evil which the Holocaust raises would have been solved, that it was merely for lack of cleverness or luck on the part of the victims that they died? And not only Hitler’s victims, but the victims of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and their various imitators: Did they too die for lack of someone with Schindler’s spunky wit? In China and elsewhere are so many still dying simply because they aren’t clever and nervy and lucky enough to survive?

The aesthetic and moral failure of Schindler’s List is a matter of misplaced emphasis. A dramatic representation of Hitler’s crime should leave us shaken and humiliated on behalf of our species for the Holocaust raises the most serious questions about our collective sanity, to say nothing of our moral quality. Washington’s Holocaust Museum faces these appalling questions with courage and dignity—perhaps a little too much dignity—and without attempting an answer. Schindler’s List doesn’t face these questions at all, nor does it ask its audience to face them. What it provides instead is an opportunity to transcend them by concentrating on an atypical good deed. In a famous scene, a beautiful boy is up to his shoulders in a reeking latrine. His expression is troubled and angelic, an expression that denies the experience of being in a real latrine, as the film itself evades the real lesson of the Holocaust.

When our trade negotiators returned to their Beijing hotel rooms and tuned their television sets to the Academy Award presentations, how many of them, I wonder, recognized the irony of their situation? And what about the rest of us? How many of us who watched the presentations at home were moved by Spielberg’s account of the Holocaust to urge our congressmen that in the case of China human rights should override even so important a cause as trade, that the Commerce Department should bow to the State Department and cancel its plans to bring one hundred Chinese trade officials to Washington next month and send an American delegation to Beijing in August, unless the Chinese government respects the human rights of its political prisoners? Schindler, after all, was willing to risk ruining his business and losing his fortune for the sake of saving lives, but the admirers of Spielberg’s film in their Academy Award chatter have said nothing about China, whose crimes are no less evil than Hitler’s.

Hitler’s immense crime was unique in its obsession with race. But it was not the first and certainly not the last case of mass murder in our century. Stalin is said to have killed at least twenty million, and this doesn’t take account of the prelude to his crimes in which millions were killed by Lenin during his brief reign. Mao, for whom the death of millions was a matter of utter indifference, killed even more. From the point of view of mass murder, ours has been a ghastly century, surely the worst in all history, for our tyrants inherited not only unprecedented technological means but ideologies that both rationalized mass murder and required it. In the Eighteenth Brumaire, Marx urged future revolutionaries to “smash” the bourgeois remnant, advice that Lenin underlined in his own copy and handed down to his followers.

Advertisement

Such ideas did not come from thin air but from the perversion of widely shared and still respected intellectual tendencies of the recent past, tendencies that arose, as Richard Pipes argues in his histories of the Russian Revolution and the early Bolshevik period, from the great philosophical and moral achievements of the Enlightenment. It was the optimistic belief that humanity can remake itself, Pipes argues, that soon led to the propagation of mass terror, for not everyone was willing or able to be remade according to the official plan, and it was these people who had to be smashed. With tens of thousands of warheads—themselves the perverse product of the most benign scientific intentions—in the hands of leaders whom no sane person should trust, will our century prove to be only the overture to horrors unimaginably worse? And who will be our Schindler then?

Hitler’s crimes are particularly poignant to us because they occurred so to speak in the house next door—in Anne Frank’s house. The victims were ourselves at barely one remove. The pity and terror that we feel are entirely personal. In the case of Stalin’s crimes, however, which preceded Hitler’s and continued long after Hitler’s death, millions of otherwise civilized Westerners simply turned away while countless others, most of them educated and humane and appalled by Hitler’s murders, defended Stalin’s camps as part of a necessary historic process leading to the eventual demise of the bourgeoisie. In any case, the Soviet victims in their faraway country with their unpronounceable names and odd clothing were seen as nothing like us. Perhaps for them death was different, as perhaps it is for the Chinese, whose strange lives most of us can barely imagine.

For this repeated indifference to our stated values our culture has paid a huge price in the form of lost confidence. No matter to what absurd extremes the literary theory of deconstruction has been carried in our universities, the plain fact is that we have taught ourselves and our children to regard the conventional discourse of our civilization with the utmost skepticism, so that from high culture to low—from Plato and Shakespeare all the way down to the White House and still further down to the House of Windsor—we now, as a matter of habit, dismantle everything, leaving only the most fragile spiritual and cultural ground beneath us.

Perhaps this is why Schindler’s List is so admired and why its partisans defend it with such unshakable sentiment. Schindler’s List provides something to trust. But in these corrosive times Spielberg’s charming trickster is unlikely to be trusted for long. And meanwhile will anyone be drawn by the film to see the connection between Nazi crimes and those in China and elsewhere and risk his factory and fortune as Schindler risked his? Schindler’s List, as its admirers insist, makes us face the Holocaust yet again. But it has also encouraged us to face the Holocaust in a most complacent and self-serving way.

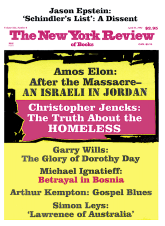

This Issue

April 21, 1994