In the summer of 1832 a cholera epidemic ravaged New York City and something like a third of the population fled. One of those who remained behind, alone in his family house, was thirteen-year-old Walt Whitman, whose job as a printer’s apprentice kept him city-bound. His parents must have been terrified that he would be one of the epidemic’s victims. Let’s assume he was. And assume, likewise, that Emily Dickinson, whose childhood illnesses caused her to miss whole terms of school, failed to reach adulthood. Neither of them, that is, lived long enough to become poets. What would the map of nineteenth-century American poetry now look like?

It’s a question implicitly but powerfully raised by this new Library of America two-volume set edited by John Hollander. Needless to say, it scants neither Whitman nor Dickinson; the complete Leaves of Grass is here (as well as another hundred pages of Whitman), and one hundred and seventy-two Dickinson poems. But these paired volumes in their range and intelligence and sheer comprehensiveness do more than any predecessor to populate that sparse mountain at whose summit Whitman and Dickinson—those two colossi—have long stood.

Their shared reign has no counterpart in twentieth-century American literature—or in the prose of their own era. If from the pantheon of nineteenth-century American fiction writers we were to remove, say, James and Twain, the resulting holes would be tremendous, but we still would have Irving, Cooper, Hawthorne, Melville, Poe, Jewett, Howells, Harte, Chopin, Crane. Poetry is another matter. It almost seems that Whitman and Dickinson are nineteenth-century American verse. To imagine the landscape without them is like imagining Colorado without the Rockies, Louisiana without the Mississippi. Bereft of our primary landmarks, we hardly know where we are.

While inviting us to contemplate the field without the two of them, the anthology also manages, ironically, to advance their supremacy. For anybody who has ever had trouble appreciating either poet, I can’t think of a course of action more likely to clarify their virtues than a thoroughgoing immersion in their contemporaries. We’ve grown accustomed to reading Whitman and Dickinson in conjunction with modern poets—beside whom they still succeed in looking innovative and arresting. But their triumphant originality emerges all the more vividly when they are placed beside not Eliot, Cummings, Pound, Moore but beside Henry Timrod, James Russell Lowell, John James Piatt, Nathaniel Parker Willis.

Criticism abhors a vacuum, and if Whitman and Dickinson had never appeared, other reputations would have expanded to claim our attention. Who would now loom as the century’s paramount figures? Longfellow and Poe? Whittier and Bryant? These two volumes do what anthologies so frequently promise but so rarely achieve: they inspire us to reassemble the landscape.

When you add in the biographical and textual notes, there are more than two thousand pages here—more than a thousand poems, more than a hundred and fifty poets. In its magnitude, this isn’t a collection one easily steps back from in order to gather together a few summary observations. My own were scattered, but I suppose the overriding impression was of the remoteness of this material to what’s being written today. Most of these poems feel distant. It isn’t so much a matter of alterations in tone and diction—considerable though these are—as of a dissolution of loyalties. Somewhere along the line, for poets and the general reading public alike, our ties to this body of poetry seem to have frayed.

It’s certainly difficult to envision this anthology sparking any sort of outrage. Are we going to see many critics, driven not by some cheap impulse to appear superior but by a heart-sore sense of loss, lamenting the absence of this or that verse by Philip Freneau or Washington Allston? One can no more picture a nineteenth-century collection’s stirring up this kind of discontent than a twentieth-century anthology’s pleasing most everyone.

The poems of even the early decades of the twentieth century, whose authors’ roots lay deep in the nineteenth, press urgently upon us. Pound, Williams, Frost—these are artists who inspire feelings of contention, as the greatest of their immediate predecessors do not. The contrast sharpens when we look to lesser figures. While modern poets like Jeffers or Bogan or Ransom may be considered “minor,” they can ignite spirited debate as William Vaughn Moody or James Whitcomb Riley or Louise Imogen Guiney no longer can.

The remoteness of so much nineteenth-century verse stems partly from the striking fact that many of the its finest poets—Melville, Emerson, Poe, Thoreau—eclipsed their own poetry by writing still finer prose. One would scarcely have it otherwise. (Melville was at times a marvelous poet, but who would trade Moby-Dick for his collected verse?) Nonetheless, in turning reflexively to their prose when we decide to explore Melville or Emerson or Poe or Thoreau, we marginalize much of what’s best in nineteenth-century poetry.

Advertisement

We might feel closer to this material had it not been such a bleak era for comic verse. By and large, the anthology seems almost determinedly unfunny. When its poets attempt to shake off their firm-jawed earnestness, the characteristic result’s a heavy-stepping whimsy. What amusement these pages do supply is often unwitting, derived from verses whose solemnity presents irresistible grist for the parodist:

Woodman, spare that tree!

Touch not a single bough!

In youth it sheltered me,

And I’ll protect it now.

Or:

“Shoot, if you must, this old gray head,

But spare your country’s flag,” she said….“Who touches a hair of yon gray head

Dies like a dog! March on!” he said.

Perhaps the failure here is simply one of missing progenitors; the contours of an entire century’s verse might have looked different had America been blessed at the outset, as England was, with the great comic genius of a Byron. Clearly, any culture whose Byron substitute is Christopher Pearse Cranch (“His horn is so long, and he blows it so strong, / He would make Handel fly off the handle”) or Joseph Rodman Drake (“Go on, great Painter! dare be dull; / No longer after nature dangle”) is in a bad way for humor.

In our own century, especially the first half, good comic verse writers were abundant enough that we can now cavalierly slight them. But if Phyllis McGinley or Dorothy Parker—charming presences who don’t regularly make their way into our anthologies—could somehow have been transported back a century, she would doubtless have flourished as a comic master. Certainly, when we consider the best of twentieth-century light verse lyrics—poems like Frost’s “Departmental” and “The Telephone,” Howard Nemerov’s “A Primer of the Daily Round,” Howard Moss’s “Tourists,” Ogden Nash’s “The Private Dinning Room”—there’s nothing in the nineteenth century to approach them. (The one exception I can think of belongs to an allied genre: children’s verse. Eugene Field’s “Dutch Lullaby,” otherwise known as “Wynken, Blynken and Nod,” and his “The Duel”—both included in the Hollander anthology—are as winsome as anything in that Child’s Garden of Verses of his exact English contemporary Robert Louis Stevenson, if not quite on a level with Edward Lear’s “The Owl and the Pussycat.”)

Wherever our observations about it begin, this anthology prods us ultimately to confront the question of whether poetry has lost some central place in our culture. It’s an issue that colors much current poetry criticism, and that served as a pervading theme for the leading poet-critic of our age, Randall Jarrell, whose four volumes of essays worry it again and again. It’s a divisive issue—some contemporary poets taking perverse comfort in their perpetual social irrelevance (we’ve never counted…), others defiantly pointing out signs of a grass-roots resurgence (everybody and his uncle is now enrolled in a poetry workshop…).

The anthology makes a strong case for poetry’s loss of centrality. It isn’t an issue merely of the fame granted to many of the poets assembled here (not only prolific and august figures like Longfellow, but those who brought renown on themselves with a single lyric, as did Elizabeth Akers Allen with her “Rock Me to Sleep,” or Edwin Markham with his “The Man with the Hoe”). Nor of the sheer number of prose writers who intermittently resorted to verse (virtually everyone…not just Poe, Emerson, Thoreau, and Melville, but Hawthorne, Harte, Howells, Henry Adams, Bierce, Jewett, Wharton, Chapman, Santayana, Crane).

No, one feels the loss of centrality in the poems themselves, in the poised, unself-conscious way in which they air their views on the varied concerns of the day: abolition, the Civil War, temperance, Bismarck’s politics, the advent of ironclad ships, humanitarian aid for victims of the Great Chicago Fire. These are poems that take for granted their role and relevance in social and political debate—as well they could, since the public figures they address might plausibly be poets themselves. Hollander includes verses by two presidents (Lincoln and John Quincy Adams), and by all sorts of lesser statesmen and public figures: secretaries of state, diplomats, mayors, congressmen, judges, ambassadors, commissioners, educational administrators, priests…. Perhaps the greatest benefit these volumes provide is to recreate an era and an atmosphere in which “Let My People Go,” Stephen Foster’s “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair,” John Rollin Ridge’s “The Stolen White Girl,” Bret Harte’s “What the Bullet Sang,” Henry Adam’s “Brahma and Buddha,” Emma Lazarus’s “The New Colossus” (“Give me your tired, your poor./Your huddled masses…”), and Ernest Thayer’s “Casey at the Bat” might spring out of a common milieu.

Advertisement

One could grow far more sentimental over poetry’s loss of position were the verse of the nineteenth century brighter and more memorable. But to judge by depth—the number of poets occasionally capable of resonant, haunting verses—American poetry is undeniably healthier today than a hundred years ago. Even so, the forfeiture of any meaningful social role is a grievous casualty on the road to excellence. Posterity may view ours as the century when American poetry found its voice and lost its audience.

How are those readers who have proceeded resolutely through both volumes apt to feel when they turn its final pages? If they’re like me, gratitude for an editorial task well done will be the primary emotion. Formidable amounts of work clearly went into this project. One doesn’t envy Hollander the job of combing one more sprawling, multicanto epic about Columbus or the Seminole wars for a viable excerpt. I know of no other anthology of the period that begins to match this one’s comprehensiveness. In addition to conventional lyrics, one finds here Christmas carols, anonymous folk ballads, Indian chants, popular songs, African American spirituals, and hymns. Hollander has performed the essential task of compiling a sort of American Collected from which—through criticism, classroom analysis, rival anthologies—an American Selected might be arrived at.

One is grateful, too, for all kinds of quirky revelations. Who would have guessed that what are almost definitely the two best-known American poems would be written by men who were born in the same year—1779—and whose work is otherwise forgotten? (I’m thinking of Francis Scott Key’s “The Star-Spangled Banner” and Clement Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas.”) Or that Melville could sound so much like Lewis Carroll: “Within low doors the boozy boors/Cat-naps take in pipe-bowl light”? Or that an American poet published a novel entitled Keep Cool in 1817? Or that Trumbull Stickney once composed three lines as surreally odd and lovely as these:

I hear a river thro’ the valley wander

Whose water runs, the song alone remaining.

A rainbow stands and summer passes under.

But if gratitude comes first, fatigue follows closely behind. One can hardly overstate how aesthetically destitute much of this material is. An accomplished poet must never be held responsible for his hapless followers, but it’s tempting to resent Wordsworth as you come upon yet another (and yet another) not-so-much-tranquil-as-tranquilized meditation on the splendors of the American landscape. It’s a real shame—one of the great squandered opportunities of American literature—that at a time when a number of our painters (Church, Cole, Bierstadt) stood alertly awestruck before the opening outreaches of the American landscape, our poets responded mainly with formula and piety. The anthology is stocked with passages like this:

Sweep on, O river. Thou dost bind

The mighty Lakes with thy soft sheen

Of silver water; Huron’s blue,

And dark Superior, and the green

of Michigan do come to thee,

And flow where thou dost say, thy shore

Doth feel their coolness hasting by,—

But haste not, river;—stay where I

Love thee, remember thee, evermore.

It’s surprising, in truth, just how rare among these one-hundred and fifty-plus poets is any avid, painterly eye—how seldom one comes upon some discrete image that can be held up for admiration.

Seeking color of any sort, I often dove into the biographical notes, which turned out to be not only exemplars of thoroughness but, unexpectedly, reservoirs of humor and pathos. What a range of things these poets did! Today, it sometimes seems most poets lead lives interchangeable with those of attorneys or accountants—the difference being that the “firm” whose hierarchy they climb is the university. A century ago, poets wrote less interesting poems and lived more interesting lives. Where is the contemporary poet who fought pirates in the Caribbean and later had to flee Mexico after killing an adversary in a duel (as Edward Coote Pinkney did), or played Juliet at Covent Garden (Fanny Kemble), or was elected president of the New York board of education (Josiah Gilbert Holland), or, having been jailed as a horse thief, escaped and went to live with the Indians, later campaigning, unsuccessfully, for Supreme Court justice of Oregon (Joaquin Miller), or proved instrumental in the recovery of Giotto’s portrait of Dante (Richard Henry Wilde), or patented a rotary engine and a walking doll (Henry Clay Work), or served as minister to Turkey (George Henry Boker), or received from the emperor of Japan the Third Class Order of the Sacred Pine (Ernest Fenollosa) or became world-famous for a dramatic performance that involved crossing the stage strapped to the back of a horse (Adah Isaacs Menken)?

My fatigue with some of the poems went hand in hand with a wish for guidance; I often found myself wanting to hear Hollander explain why he’d made the inclusions he had. While I admire the Library of America’s policy of forgoing introductions and extensive notes, in this case I would have preferred a more visible editorial hand, and I hope Mr. Hollander, barred from presenting his views in the text itself, will publish them elsewhere. It would be interesting to know which poems he considers important for historical reasons and which purely for their aesthetic merits. There are verses here that I find utterly derisory and yet whose inclusion I wouldn’t question. I’d far rather work a shift on the New Jersey Turnpike, collecting fares and toll cards, than spend my day reading the collected works of Charles Godfrey Leland, who specialized in a comic German-English pastiche (“There’s a liddle fact in hishdory vitch few hafe oondershtand”). But in view of Leland’s once-wide popularity I can appreciate why Hollander offers four samples of his work.

For the life of me, though, I can’t see that I’ve been instructed or otherwise enriched by Philip Pendleton Cooke’s “Orthone,” or Timothy Brooks’s “Our Island Home,” or Forceythe Willson’s interminable “In State.” And while it has long warmed my heart to know there was once poet with the unsurpassable name of Bliss Carman, I’m sorry to have diluted my delight in his existence by finally sampling some of his verses (they appear under the name of his collaborator, Richard Hovey). The same could be said of Manoah Bodman or Epes Sargent, whose lives’ closest brush with authentic creativity evidently took place at their christening.

I suspect most readers will come away from the anthology with some feelings of disappointment, directed not at Hollander (it’s hard to imagine anyone’s doing a better job) but at the material itself. Slogging through big swatches of work by little-known or unknown names, the reader naturally hopes to come upon a few obscure, perfect jewels. Not long ago, Christopher Ricks, editing an anthology that overlapped this one in years but not in territory, offered many such unexpected gratifications in his New Oxford Book of Victorian Verse. But America in the last century, unlike England, apparently gave birth to few prizes of this special sort. One of Thomas Hardy’s great ambitions was to write a lyric worthy of that most celebrated of nineteenth-century English anthologies, The Golden Treasury—a collection that served him as a benchmark. We, too, might regard it as one, and ask ourselves: How many nineteenth-century American poets wrote verses that might be placed in an anthology purporting to amass “all the best original Lyrical pieces and Songs in our Language”?

The situation crystallizes when we focus on the sonnet, of which there is a profusion here. Even readers who find sonnets congenial (as I do) may eventually experience a sinking heart on turning a page and confronting another rash of genteel productions, conscientiously modeled on Wordsworthian or Keatsian lines. There’s “nothing wrong” with most of these—save that they seem tailored to the hope that nothing will be wrong with them. Even the most sympathetic reader must at last object to unobjectionable verse.

Naturally, an exaggerated joy results when you encounter something that jostles with reckless energy. Some of the sonnets of Jones Very—whose best poems, according to Yvor Winters, “are as convincing, and within their limits as excellent, as are the poems of Blake, or Traherne, or George Herbert”—have a handsome vigor. Still more exciting to me were those of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman, who despite having a thoughtful advocate in Denis Donoghue, probably remains even less known than Very. Tuckerman had a flair for visual imagery (“the old grasshopper molasses-mouthed,” “the nine moonstars in the moonless blue”), and an ability in the clinch—in the sestet—to elevate and transform the commonplace. Occasionally, he put a whole sonnet together beautifully:

His heart was in his garden; but his brain

Wandered at will among the fiery stars:

Bards, heroes, prophets, Homers, Hamilcars,

With many angels stood, his eye to gain;

The devils, too, were his familiars.

And yet the cunning florist held his eyes

Close to the ground,—a tulip- bulb his prize,—

And talked of tan and bone-dust, cutworms, grubs,

As though all Nature held no higher strain;

Or, if he spoke of Art, he made the theme

Flow through box-borders, turf, and flower-tubs;

Or, like a garden-engine’s, steered the stream,—

Now spouted rainbows to the silent skies;

Now kept it flat, and raked the walks and shrubs.

This strikes me as praiseworthy for a wealth of reasons: the rigorous back-and-forth balancing between the terrestrial and the supernal; the ironyedged praise of taciturnity in a poem that borders on the voluptuous; the little pun on “spouted”; the way in which, having flung his rainbows, the poet returns firmly to earth in that homey terminal rhyme of grubs/tubs/shrubs. It’s as good a sonnet, I think, as any in the Hollander collection, and amid so much dun company it glows luminescent. Yet the light changes utterly when it’s placed beside the best nineteenth-century English sonnets. How does it shine when set next to “Ozymandias”? Or “The World is Too Much With Us”? Or “As kingfishers catch fire…”? America in the nineteenth century, for all its umpteen sonnets, may have produced none of the first rank. (A case might be made for some of Edwin Arlington Robinson’s tough and dextrous sonnets, though most of his best poems belong to the twentieth century.) For work of this highest sort, we maybe had to wait for Frost, and his “Design” and “The master-speed” and “Never Again Would Birds’ Song Be the Same” (sonnets that show—I can’t help chauvinistically adding—a greater mastery of the form than that of any English poet in this century).

Born in 1874, Frost might have invigorated nineteenth-century poetry had he been at all precocious. But he was something of a slow learner, who didn’t begin steadily excelling until his forties. His example highlights a peculiar trait of last-century American verse. Whitman and Dickinson, its two major poets, achieved their status the hard way: by fabricating intensely original work, by subjecting the lyric poem to a wholesale revision. What might have seemed the easier path—the marrying of existing English forms to American subjects and diction—proved oddly more intractable. This was a task that fell to, among others, Frost and Bishop, theirs being the art of (as Howard Moss wrote in Bishop’s praise) seamlessly combining form and relaxed diction. On the rough, hardscrabble American road to Parnassus, it initially proved easier to slough off the English heritage than, gently, to bend and modify it.

Whitman and Dickinson were scarcely unique in seeking a radical versification—unique, rather, in designing something fully adapted to their individual gifts. They had as contemporaries a number of experimentalists, of whom three seem particularly interesting: Longfellow, Poe, and Lanier.

For modern readers, Longfellow’s “Hiawatha” comes shrouded in so many quaint trappings (as does Longfellow himself, who reminded us that “Life is real! Life is earnest!”) that it’s easy to lose sight of what a potentially ground-breaking poem it was. Borrowing from the Finnish Kalevala meter, Longfellow worked to upend orthodox harmonics by substituting falling trochaics for rising iambics, by forgoing rhyme, and by lacing his poems with Indian vocabulary and place names and kennings (e.g., Moon of Strawberries = June). Formally, the poem is far more carefully worked out than Coleridge’s “Christabel,” which likewise sought to import into English a new versification, and far more sustainable than the rhyme-cramped stanzas of Poe’s “The Raven,” which similarly trafficked in trochees. Potentially, what more weird and wonderful poem could there be than an epic fusing of that most American of subjects—the Indian—with an obscure European form associated with oral heroic tales and Christian legends? One of my few complaints with Hollander’s collection is that he supplies only two passages from “Hiawatha.” (Another is that I found something like a half dozen minor inaccuracies in the two volumes—mispellings, jumbled homonyms, a computational slip—which left me with an uneasy feeling whenever I’d confront an odd-looking word or conjunction.) “Hiawatha” is the kind of poem whose charms, unfortunately finite, require sufficient space to let their incantatory cadences roll. Life (in addition to being real! and earnest!) is a mystical undertaking—surmounted, as Longfellow wrote in a lesser-known lyric, by “towers of clouds uplifting/In air their insubstantial masonry.” If his bravest designs finally, like clouds, fail to hold together, the grandeur of his architecture has an enduring appeal.

Very little, by contrast, was architectonic about Poe. He is often at his best when most delirious (and sometimes at his worst: “Vastness! and Age! and memories of Eld!/Silence! and Desolation! and dim night!”), and his most successful poems (“The Raven,” “Annabel Lee,” “The Bells”) assume widely divergent forms. They are united by a heavy reliance on rhyme, a device without which his poetic career is as inconceivable as is, in the twentieth century, John Crowe Ransom’s. Poe was so trusting of rhyme’s ability to induce a tranced music that he would say nearly anything to keep the music flowing. In most of his poems there’s a moment when the whole enterprise looks absurd:

In the silence of the night How we shiver with affright

At the melancholy meaning of the tone!

* * For the moon never beams with- out bringing me dreams

Of my beautiful Annabel Lee

* * “Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see, then, what threat is, and this mystery explore—“

(Only an immortal, an absolutely unbudgeable bird, could survive those rhymes of “that is,” “lattice,” and “thereat is.”) As a prosodist, Poe is most compelling when fracturing his verses in pursuit of a music of excess:

How the danger sinks and swells,

By the sinking or the swelling in the anger of the bells—

Of the bells—

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells,—

In the clamor and the clangor of the bells.

In the long run, Sidney Lanier probably offers the greatest rewards of the three. He had, like Longfellow, a scholar’s systematic bent, which culminated in his pioneer study, The Science of English Verse. He shared with Poe both a very un-Longfellowish conception of the poem as a variable, organic entity, whose meter or rhyme could be revised at any point within the poem, and a taste for dissonance.

His “Hymns of the Marshes,” written at the close of his short life (he died in 1881, at the age of thirty-nine), are uneven but wonderful: at their best, one of the pinnacles of nineteenth-century American verse. Gerard Manley Hopkins is the unmistakable tutelary genius of their dripping, sun-dappled terrain. His influence is palpable throughout: in the queer, urgent-feeling coinages (wholewise, bottomry, unjarring); in the impulse to rhyme word-clusters rather than single words; in the craving to capture a fixed location’s essence (Lanier’s swamps are no mere metaphors—no Sloughs of Despond—but genuine, mucky lowlands whose frogs boom and whose mosquitoes draw blood); in its desire to subject nature to a sort of stop-watch, resolving even the fleetest and smoothest motions into a series of frozen instants. What the poems lack is Hopkins’s fierce, dizzying compression; their marvels are too thinly inlaid.

One hesitates to dilate on Hopkins’s influence only because he was virtually unpublished when “Hymns of the Marsh” appeared; were it not absolutely impossible that he’d influenced Lanier, we would have an open and shut case of artistic ancestry. As it is, the two poets underscore the complexity of all such questions of lineage and development. Ultimately, the Library of America volumes challenge us to chart the links between the last century and the best of our own. But that’s a tricky business, and having opened with one hypothetical—in which Whitman and Dickinson perished prematurely—I’d close with another.

Assume for a moment we didn’t know what succeeded these two volumes—that our acquaintance with American verse halted at the turn of the century. Who among us, by what elaborate processes of extrapolation and clairvoyance, could have foreseen that in the next quarter of a century our poetry would resemble this:

Of dowager Mrs. Phlaccus, and Professor and Mrs. Cheetah I remember a slice of lemon, and a bitten macaroon.

Or this:

if I in my north room

dance naked, grotesquely

before my mirror

waving my shirt round my head

and singing softly to myself:

“I am lonely, lonely…”

Or this:

The tea-rose tea-grown, etc.

Supplants the mousseline of Cos,

The pianola “replaces”

Sappho’s barbitos.

Or this:

will anyone tell him why he should

blow two bits for the coming of Christ Jesus?

?

??

???

!nix, kid

Or this:

the bat

holding on upside down or in quest of something toeat, elephants pushing, a wild horse taking a roll, a tireless wolf under

a tree, the immovable critic twitch- ing his skin like a horse that feels a flea,

the baseball fan, the statistician—

At the turn of the century, the acclaimed living masters of American verse were poets like James Whitcomb Riley, John Banister Tabb, Richard Watson Gilder, Richard Hovey. A mere twenty-five years later we had Eliot, Williams, Pound, Cummings, Moore, and all the rest.

It sometimes seems it’s the business of the critic to establish that the domain of literature contains no bastards—no children of unknown parentage, no foundlings, no changelings. Every poet’s pedigree can be dutifully traced. And no doubt we could locate forebears, domestic and foreign, for each of the Modernists listed above. Still, what they represent in the aggregate, as a collective blossoming of prodigious proportions, surely wasn’t to be foreseen.

Our culture has been blessed with a number of such accelerated blossomings in this century—the flowering of the pop song between the wars, the screwball comedy of the Thirties, the growth of be-bop jazz. One doesn’t want these happy miracles to be explained away too hastily or too neatly. Nonetheless, as twentieth-century American poetry approaches its end, it’s probably time to attempt to put the nineteenth into focus; this anthology comes none too soon. In a few years we’ll have turned a calendrical corner, and Whitman and Dickinson and even early Edwin Arlington Robinson will lie two centuries behind us. This pair of volumes asks us to glance backward, while keeping one eye on the present and its murky bonds to our poetic tradition. And asks us to peer hesitantly into the future—seeking to divine what, were it to arrive tomorrow, a further refiguring of American poetry might look like.

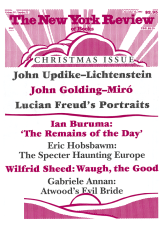

This Issue

December 16, 1993