Editors’ Note: In the June 10 issue Brian Urquhart, former Undersecretary-General of the United Nations, proposed that a UN volunteer military force be organized to meet the need for an “international volunteer force, willing, if necessary, to fight hard to break the cycle of violence at an early stage in low-level but dangerous conflicts, especially ones involving irregular militias and groups.”

“Clearly,” he wrote, “a timely intervention by a relatively small but highly trained force, willing and authorized to take combat risks and representing the will of the international community, could make a decisive difference in the early stages of the crisis.” Such an international force, Mr. Urquhart said, “would be under the exclusive authority of the Security Council and under the day-to-day direction of the Secretary-General.”

Several comments on Mr. Urquhart’s proposal appeared in the June 24 issue. Six further statements on the proposal follow.

Robert Oakley

Sir Brian Urquhart has since World War II been one of the foremost thinkers and doers who have been concerned with the role of the United Nations in international peace and security. First, he worked directly inside the system with Ralph Bunche and successive secretaries-general in planning and conducting United Nations peace-keeping operations. More recently, from the outside, he has remained keenly interested and actively involved as a scholar, writer, commentator, and adviser, contributing to both long-term studies and near-term decisions on how the United Nations can do a better job. Therefore, when he says that the time has come to put into effect Trygve Lie’s original idea of a permanent UN military force, we should all take notice.

There is no denying Sir Brian’s point that traditional UN peace-keeping operations cannot deal with the new waves of largely intrastate violence, and with the humanitarian crises arising from local conflict, that are sweeping the post–cold war world. Similarly, this trend will undoubtedly continue, even as the likelihood of major conflict between states diminishes. In response to this new situation—which includes cooperation between the US and Russia on seeking solutions instead of exacerbating local and regional unrest—thirteen UN peace-keeping operations (PKOs) were begun between 1989 and 1992. This is equal to the total number approved between 1945 and 1989. However, many of the PKOs have been too slow in getting organized, too small and too weak logistically for the task. Frequently their mandates and missions have been imprecise or inadequate. As a result, UN forces have often been unable to achieve success and have become bogged down in a deteriorating environment where the violence they were supposed to stop continues largely unabated around them.

Under such circumstances, the international community has several alternatives: to mount much larger, more forceful initial or rescue operations (as in Somalia); to acquiesce in a compromise in an attempt to minimize the loss of life (as in Bosnia); or to sit on its collective hands with the UN force an impotent witness to continued conflict, death, and destruction (as in Angola). In view of the large cost in money and military resources, as well as the risk of casualties, organizing a large, forceful operation is not going to be a frequent choice. For the US alone, the operation in Somalia required, during a period of five months, a force of almost 30,000 and it cost over 1 billion dollars; and the UN force in Somalia of some 25,000 men cost, during one year, 1.5 billion dollars. In Cambodia, the peace-keeping operation involving over 25,000 personnel has cost about 2 billion dollars. The most realistic choice therefore would seem to be between not committing UN peace-keeping forces at all or acting much more rapidly and more decisively, before the situation on the ground disintegrates to the point that the only means of dealing with it involves large forces. Sir Brian’s proposal could achieve this.

Aside from the costs in money, men, and equipment, the major obstacles to a standing UN force have been, and remain, the reservations of thoughtful military leaders about inadequate command and control, the lack of a clear mandate and clear rules of engagement, and insufficient resources for the specific mission to be undertaken. The usual UN peace-keeping practices, including command and control from a UN headquarters whose planning has been vague, and whose logistics have been weak, are widely considered to be militarily unworkable. If this system continues unchanged, no self-respecting military commander (or political leader) would willingly send his or her forces into harm’s way “under the exclusive authority of the Security Council and under the day-to-day direction of the Secretary-General, as Sir Brian puts it. This traditional approach is a formula for confusion, failure, and potential disaster.

Strategic guidance by a committee and tactical decisions by remote control are simply unacceptable to responsible military authorities. In fact, as Sir Brian knows from first-hand experience, the UN force in the Congo in the early 1960s succeeded militarily in reintegrating the Katanga region into the Congo only after communications with UN headquarters had conveniently been cut, allowing the field commander to do what he considered necessary without the supervision of the Security Council, in which the Soviets would have used their veto. Secretary-General Hammarskjold wisely delegated command and control to the UN commander on the ground.

Advertisement

With respect to Somalia, the United States insisted last November on two conditions: first, on using its time-tested, combat-proven doctrine of having clear lines of command and control, with maximum responsibility given to the commander in the field, and, second, on having overwhelming, decisive force at the outset with freedom to use it to achieve the mission. This insistence played a part in the unwillingness of the Secretary-General and the Security Council to accept President Bush’s offer to make the US-led force a UN peace-keeping (or peace enforcement) operation. At that time, this US concept flew directly in the face of the traditional UN approach by which (1) peace-keeping was based upon minimal force, to be used only for self-protection; (2) most control and command functions were maintained at UN headquarters; and (3) permission was requested from local authorities before taking action.

Subsequently, UN thinking has been undergoing a major change, in good part as the result of the success of the original US-led, UN-approved international coalition for Somalia (UNITAF). The coalition was able to achieve its mission, limited though it was, very rapidly and with few casualties to international forces or Somalis—and this success came immediately after the demonstrated ineffectiveness and humiliation of a traditional UN force in Somalia (UNOSOM I), and after it became clear that serious problems were being encountered by other traditional UN forces (e.g., in Angola, Bosnia, Cambodia).

Thus the new UN force for Somalia (UNOSOM II) was established by the Security Council with generally the same command and control procedures, rules of engagement, and freedom to use force that had applied to UNITAF. The UN commander, Turkish Lt. General Cevet Bir and UN Special Representative Admiral (ret.) Jonathan Howe are, in theory and according to their mandate, as much in command of the twenty-odd individual foreign units as US Marine Lt. General Robert Johnson was of the twenty-odd foreign units comprising UNITAF. The latter was molded into an effective force in which the different national units accepted standard, vertical military command and competed with one another to maintain high standards of discipline in carrying out their mission. While Lt. General Bir has a much broader mission and larger territory to cover with fewer forces, he and Admiral Howe were able to maintain the essentials of command and control among UNOSOM II units until early June when Pakistani forces were ambushed. Although overall effectiveness was not seriously jeopardized the ensuing events showed the need for still stronger command and control, as well as training of all units for the special responsibilities and situations likely to arise in peace-keeping situations.

US troops are participating for the first time in a UN peace-keeping operation. The US Congress as well as the administration have approved this clear departure from the previous US policy of nonparticipation and also approved 300 million dollars in the fiscal year 1994 Department of Defense budget for peace-keeping. This will henceforth be an integral part of US military planning and operations, as it has been for years with Canada and the Scandinavian countries.

The new approach also seems to be gaining ground in current UN thinking about future peace-keeping operations. It is in line with Sir Brian’s proposal for more effective UN forces—even though it differs importantly with respect to command and control. For the present, UN thinking is largely based on the more traditional approach by which member states designate existing units for duty in individual peace-keeping operations. As Sir Brian has suggested, this could be modified to provide for a small standing force, an innovation that would probably be readily accepted by a number of the nations that could be expected to supply troops. Such a force might best be made up of individual national battalions of ground forces plus national support units (transportation, engineers, communications, etc.). It should have a carefully selected staff of officers with experience working both with one another’s military establishments and with international coalitions. To broaden the base of troop contributions, different member states could, under a system of rotation, supply units every year or so.

The alternative proposal of an all-volunteer force of assorted individuals from many different countries somehow brought together under UN control would, in my view, be militarily unworkable. To be effective, it would require the sort of tough training and discipline, as well as the unified basic outlook—and the shared military doctrine on the part of the staff—that is to be found in the French Foreign Legion or in the United States Marine Corps. This would require a complete change in the ways of thinking now characteristic of the UN, plus many years of hard work. Moreover, most member states would probably prefer to volunteer their own forces than see the UN with a wholly independent force, even though Security Council approval, subject to veto, would be required before any force was actually used.

Advertisement

The new approach also needs to be formulated with care, despite its apparent attractiveness. The UN members who contribute troops can only rarely, and after considerable debate, be expected to tolerate a large UN operation that may become engaged in major combat, with the likelihood of high casualties on all sides. The political as well as military and financial costs are seen as simply too high. These reservations are even stronger for a standing force than for a single operation. As it is, the UN is unable to obtain all the forces it is requesting for some ongoing peace-keeping operations, and its peace-keeping budget is badly overdrawn.

Moreover, one needs to take into account that, notwithstanding the current, almost exclusive concentration of the mass media on Bosnia, there are today at least a dozen violent, life-destroying crises that could benefit from the help of the UN (e.g., in Nagorno-Karabakh, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Rwanda, Sudan, Zaire, Haiti, etc.). The probability is that there will be many more. The use of major UN forces for so many operations is simply not in the cards. Should UN members therefore shut their eyes to many actual or potential conflicts?

In order to deal with this agonizingly difficult dilemma more effectively, the UN and its members need to act much earlier and more decisively to try to head off or resolve crises—before so much violence has taken place that emotions become extremely hard to cool, and before actual and imminent loss of life by conflict, starvation, and disease reaches the acute stage. A small, permanent UN force could be very important for this purpose, and it should be complemented by an array of procedures for peaceful conflict prevention and conflict resolution plus the prospect of international help for rehabilitation and reconstruction, not only relief, as well as the threat or use of economic and political sanctions. A standby force of no more than a reinforced brigade (5,000 soldiers) would not be so costly financially or in the troops that would be required; nor would it pose so unacceptable a threat of becoming involved in major combat that it would necessarily deter UN members from approving it.

Proper command and control procedures and other issues of military doctrine would obviously need to be agreed upon, as well as the rules by which the Secretary-General and the Security Council would deploy the force. Logistic support would have to come from UN resources or those provided by member states. However, the concept is reasonable and could probably be approved after adequate consultation, particularly if it is seen as part of a plan for more systematic, more effective, and less costly longterm UN operations.

When it comes to putting the idea into practice, it would seem preferable to consider, at first, deploying only one or at most two battalions for particular operations. Such an initial deployment would be a strong signal of international concern and determination to help, before things get out of hand. A small force could move almost immediately. Deployment could be more rapid and would cost less if it could make use of stockpiles that would be created at several locations around the world, drawing upon the large amount of surplus equipment in the US, former USSR, NATO, and Warsaw Pact armies.

Indeed, the use of such stockpiled equipment would be appropriate for peace-keeping forces generally—for example in Somalia today—not just for a standing military force. The donor countries could maintain these supplies, and their costs for doing so and for the equipment itself could be charged off against UN peace-keeping obligations. (This would be particularly attractive to Russia, Ukraine, and other countries that are desperately short of money.) At the same time, the considerable improvements now being made in the management of the UN peace-keeping department should continue. They should include the identification of individual units from foreign military establishments that are capable and ready for use as part of a UN peace-keeping operation, should a larger force be needed.

Some might argue that such a small force would soon be rendered useless, as with past UN peace-keeping operations, and that it should necessarily be backed by a previously agreed upon UN readiness to commit major forces should the initial contingent run into trouble. I would disagree. The ultimate responsibility for resolving crises and restoring peace must be that of the peoples and leaders of the country or countries concerned. They should understand clearly that the international community is not going to become bogged down indefinitely in situations which prove intractable. If, in addition to other measures, an initial, small force fails to bring substantial improvement, the UN should feel free to withdraw rather than be obliged to protect a bad investment.

This may seem hard-hearted, but if UN intervention comes at an early enough stage it could in many situations serve as a considerable incentive to local agreement on ending conflict. If not, the UN would be justified in withdrawing, leaving economic and other sanctions in effect, with perhaps some protection for refugees and displaced persons. Deliberately “quarantining” countries or parties involved in intranational conflict in certain situations in which serious initial international efforts fail would be a more honest course of action than at present, when most UN members act almost as if crises do not exist for fear of becoming overengaged. It could encourage the UN and its members to take on more responsibility, knowing that operations would be modest in scale and limited in duration rather than open-ended. A small, standing UN force could make a major contribution to such an approach.

—Robert Oakley is the former US Special Envoy to Somalia.

McGeorge Bundy

Brian Urquhart may or may not be right to insist that we need a UN volunteer military force, but his proposal attacks the right problem. The Security Council and the Secretary-General as its executive agent do indeed require rapid access to peace-keeping forces ready and able to back them up quickly in the many missions that are marking the 1990s—eight begun in the last two years, against about one every second year in preceding decades. But as Urquhart says, the force he proposes will take years to create and recruit and organize. In the meantime there will be an urgent need for improvement in what we now do case by case. Whether or not we get an Urquhart force by the end of the century, we shall need better and faster-acting forces of the traditional sort in the meantime. The Urquhart proposal illuminates that need like a starshell, lighting up one sharp reality of cases like Bosnia, Somalia, Cambodia, and Mozambique: forces were needed before they could be fielded, and sooner would have been better from every standpoint.

It is clear that while the decisions to act must have the time they need, the act of peace-keeping gains strength from speed. Moreover, we should distinguish these two elements. In Bosnia, for example, the basic trouble was more in the absence of decisions than in any absence of early deployment; able and dedicated negotiators simply had no sufficient decision makers behind them.

The traditional way of mounting peace-keeping forces is by financing them from all members, with a rebate for the poor and a surcharge for the permanent five. Last year candidate Clinton did not like that surcharge, but President Clinton should defend it. It is in reality a reflection of the very special worldwide role of the American people and their president. It is also partly a surcharge for the power to say no—the veto—and it is a bargain. The American people will surely understand that when it is explained, and Americans will not play the great game of international security by any other rules. At the UN money is always a problem; in 1993 peace-keeping money is an urgent problem, and I cannot improve on Chairman Lee Hamilton’s grown-up view, in the June 24 issue, that Americans should do their full part to help on that front.

As Urquhart says, the forces this money pays for must be ready, willing, and able. They must also be varied, because different national forces are welcome and unwelcome in different places. The countries which have responded more than once to the Secretary-General’s invitation have learned a lot more about what is needed for such forces, and they can often react quickly. But it would not be hard to have forces even more alert, and it would not be hard to strengthen the ability of the UN to plan, to prepare, and to organize such ventures. If it is important that such forces be volunteers, that could also be arranged well in advance, and such a volunteers only force might be particularly fitting here in the United States.

So I believe that the best way to respond to Brian Urquhart’s inspired proposal is to go ahead now with the improvements it suggests in the system we have now and cannot quickly replace. For Americans that means that we should make sure that our own contributions are of a size and quality fitting to our inescapably first-rank part in the work of the United Nations. We must never forget that no problem is ever solved by the slogan, “Take it to the UN.” The UN cannot be anything but what its members do, or fail to do, in helping to make its choices and carry them through.

—McGeorge Bundy is Scholar-in-Residence at the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Sadruddin Aga Khan

In view of the ineptness of the UN Security Council in dealing with the tragedy of Bosnia and its absence of political will, I do not share Brian Urquhart’s hopes about the potential effectiveness of a UN volunteer military force. The stumbling block is not the “specter of supranationality” of the cold war days. Rather, it is the fear that such a force, once created, would compel the council to make use of it in the situations which it chooses to ignore or paper over—even if the press and television bring the carnage into Western homes and conscience.

UN troops are no longer the ones Trygve Lie—or even Boutros Boutros-Ghali—had in mind. They have now been reduced to an ineffective extension of UN humanitarian agencies and nongovernmental organizations. Like them, they have become hostages to aggression: the British and the French, both permanent members of the Security Council, consistently opposed stronger UN deterrent actions against the Serbs (or Croats) for fear of provoking attacks on their peace-keeping contingents, thus negating their very purpose and becoming an obstacle to peace-keeping or peace-making. The Bosnian “safe havens” are yet another example of bluster and impotence.

A UN volunteer military force with the excellent terms of reference and elaborate job description outlined by Brian Urquhart is a fine idea. It is certainly needed and should be established. But it will remain stillborn unless and until the Security Council revises its own “rules of engagement” by exercising more even-handedness in charter-based international peace enforcement action to deal with future conflicts. Meanwhile, like King Canute, the Big Five seem content to “order the waves to go back with small hope of practical results.”

—Sadruddin Aga Khan was the UN High Commissioner for Refugees from 1965 to 1977.

Olusegun Obasanjo

If, with the end of the cold war, the newly emerging global democratization and the deepening of cooperation among states is to be sustained, an effective arrangement to increase security and ensure a global order must be put in place. In his Agenda for Peace, the UN Secretary-General, Mr. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, described very clearly the procedures he would want the UN to adopt in dealing with conflicts at every stage. He first envisages a “peace-watch” during which UN diplomats and monitors would observe developing conflicts and try to mediate between the parties; this would be followed by a peace-making stage which may or may not involve deployment of troops. The third stage is peace-keeping, and the final stage is peace-building after the conflict.

The first stage, involving a peace-watch and preventive diplomacy, is the most economical and the least painful way to intervene in conflicts. To interject a UN volunteer military force into a zone of conflict as advocated by Brian Urquhart in the New York Review of June 10, 1993, would be, in effect, to admit the failure of such first-stage action, owing to inadequate or untimely efforts. When there is a need for a peace-watch effort involving monitors it is most likely to be deployed on the basis of international consensus if not unanimity. It will be more effective if the burdens are shared evenly, without a double standard.

Many nations in both north and south take the view that peace-watch efforts and preventive diplomacy should have the highest priority in stopping conflicts from developing into the kind of violent military clashes in which a UN volunteer military force would have to be interposed. A corps of mediators and monitors should be created and it should be at the disposal of the Secretary-General and the Security Council. The proposed volunteer military force could follow on the heels of the corps of mediators and monitors, serving as a force of interposition and of confidence-building to prevent the clash of arms. Moreover, as the Agenda for Peace emphasizes, regional organizations have an important role in both the first and second stages of conflict management by the UN; such organizations must not be ignored or cast aside in establishing and using a corps of mediators and monitors and a UN volunteer military force.

A case can be made for a force drawn from member states that 1) would be specially trained, designated for UN service, and placed under the authority of the Security Council; 2) would be under the day-to-day direction of the Secretary-General; 3) would be adequately supported with logistics and communications for immediate deployment in any part of the world. That there is a need for such force has been fairly well argued and has been agreed on, at least in principle, in most parts of the world. There are still some questions and some apprehensions about such a force, and nations will have to make a fundamental accommodation in their attitudes if it is to work.

Brian Urquhart talked of “the need for a highly trained international volunteer force, willing, if necessary, to fight hard to break the cycle of violence at an early stage in low-level but dangerous conflicts.”

That such a force would be useful in carrying out the second stage of UN action is clear; but the method of recruitment and the responsibility for training, clothing, billeting, and equipment are not clear, especially if the troops are not part of national defense forces. Neither are the conditions for engagement and discharge. Urquhart gave the impression volunteers for a “United Nations Army” would be recruited from within member nations but didn’t say how. He proposed that as an “interim” measure the forces could be volunteers from existing armed forces who would return to their national forces after a given period of enlistment was over.

Mr. Boutros Boutros-Ghali in his Agenda for Peace, page 26, proposes that

Such units from Member States would be available on call and would consist of troops that have volunteered for such services. They would have to be more heavily armed than peace-keeping forces and would need to undergo extensive preparatory training within their national forces.

The Secretary-General seems to be talking of a special force that would be drawn from member nations’ defense forces and trained, equipped, and specifically placed under the authority of the Security Council for deployment and command and control.

The volunteer nature of the troops and the force is confusing and I believe that it should be done away with unless it refers to countries which are willing, on their own volition, to contribute troops into a pool for UN deployment. If volunteering by troops is made a condition in some countries of the south, the entire national defense force would volunteer in order to get out of the morass of their national situation, while volunteers may be entirely unavailable from a country in the north whose participation is of utmost importance. Even if the force were internationally balanced so far as the nations composing it and the arms available are concerned, who will provide the additional costs of training, equipment, and communication for contingents for some countries of the south? I believe that adequate provisions for funding peace-keeping and peace-making operations could come through implementing the recommendations of the report—Financing an Effective United Nations—of the independent advisory group recently sponsored by the Ford Foundation.*

But here we come face to face with another problem. Those who will pay more in the coming years to finance the UN and the UN peace-keeping operations may be inadequately represented on the decision-making body of the UN. I refer particularly to Germany and Japan which are not permanent members of the UN Security Council. Also, the countries of the south, which are likely to be affected more than others by the specially designated national forces deployed by the UN, will require greater voice in the decision-making body to allay their fears and make them more willing to delegate sovereignty to the UN Security Council, the UN, and its specialized agencies.

Nonetheless, creation of a corps of mediators and monitors to support the Secretary-General’s first stage and a modified version of the volunteer force posed by Brian Urquhart to support the second stage would improve the processes of conflict prevention and conflict resolution by the UN.

—General Obasanjo is the former President of Nigeria.

Anthony Parsons

Some of the contributors to the June 24 issue set out the problems involved in implementing Brian Urquhart’s proposal for a UN volunteer military force that would be mandated and armed to fight, as opposed to “non-threatening” peace-keeping. I shall focus on the problem facing the UN if such a force is not created.

We are agreed that, in the post-decolonization era, wars between states have been rare, civil wars frequent. At present there are about thirty civil wars going on and no more than two or three wars between states. This will be the pattern of the future.

Aggressors and warlords have already learned that, even in the most propitious situation for international intervention since 1945, the UN will authorize and take military enforcement action only in exceptional circumstances: in interstate wars it will do so if the aggression is unambiguous, if there is a Great Power strategic interest, and if there is plenty of cash and the probability of a quick in and out operation; in civil wars only if pressure from the public and mass media is overwhelming and the risk of casualties negligible. Otherwise the UN confines itself to persuasive diplomacy, nonthreatening peace-keeping, and economic sanctions, which on their own have always been ineffective.

If the UN cannot do better than this, it will be a useful but peripheral actor in the many civil conflicts of the present and future. Saddam Hussein, Pol Pot, and the likely loser of the forthcoming Mozambique elections must have read the Bosnian and Angolan omens. God help the people of Iraqi Kurdistan, Cambodia, and Mozambique if they conclude that my analysis is correct.

It would be a different story if the Security Council and the Secretary-General had at their disposal a small but well-armed and motivated all-volunteer force on the lines of the French Foreign Legion or the Gurkhas of Nepal, where morale and military prowess derive from esprit de corps rather than national patriotism.

If such a force were given the appropriate mandates, plus Great Power logistical backup and air power, it would be an effective deterrent on a potential victim’s side of a border, or it could be used to guarantee a peaceful settlement or to enforce a fragile agreement. Kuwait in 1990, Angola, and Cambodia, as well as Mozambique come to mind. Most warlords would think twice if they knew that a military move would meet strong resistance from the outset. Conflicts usually start small and preemptive diplomacy is a limited instrument unless buttressed by force.

Most of the problems raised in this symposium could be overcome if the will was present and I trust that the Urquhart initiative will not be buried to the sound of eulogies. The only really difficult problem that I foresee is that there would be so great a demand in so many different places simultaneously that one “brigade group” of 5,000 men would be insufficient; 10,000 would be more like it.

—Anthony Parsons is the former British Ambassador to the UN.

Marion Dönhoff

Mr. Brian Urquhart proposes the establishment of a United Nations volunteer force in order to secure the possibility of preventing an outbreak of violence. In other words, this unit is supposed to back a new type of preventive diplomacy.

It seems to me that several questions arise in this context.

- Is this volunteer force meant to be established alongside the 88,000 Blue Helmet soldiers who are now stationed in ten different states and whose upkeep is estimated to cost $3.6 billion this year?

- Will this force be recruited from national armies, in which case their respective governments will certainly want to have a say in decision-making, or will they be a kind of “foreign legion”? If so, who then would be in command? And what would be the common language?

- Who will provide the military command structure, the general staff, the intelligence, and the communications system—and who is going to pay for all this?

-

Finally the most important question: Who will establish the guiding principles? Under what circumstances is the United Nations entitled to intervene—only in the event of conflict between sovereign states or also when the danger of civil war arises? Will guidelines be set up stating when and in which cases this force should become active and against whom? To what degree may pressure be applied? Is the force meant to serve mainly peace-keeping purposes or can it also be used for peace enforcement?

One wonders a bit if this concept—should it eventually become a reality—could in fact meet the aspired goal: preventing conflicts from turning into violence.

—Dr. Marion Dönhoff is the Publisher of Die Zeit.

Brian Urquhart comments

As McGeorge Bundy quite rightly indicates, my primary intention in suggesting a UN volunteer military force was to light up the sharp reality of some of the current situations—Bosnia, Somalia, and others—where it is proving difficult to make the decisions of the Security Council a positive reality on the ground. As of now, for example, the Security Council has adopted thirty-nine resolutions on the situation in Bosnia alone.

Robert Oakley has correctly underlined the need to act rapidly before a situation in a conflict area disintegrates. He has also raised, from his own long personal experience, some vital problems concerning command and control, rules of engagement, and resources. I fully agree, as, I believe, does everyone concerned at the United Nations, that much improvement is needed in the handling of field operations and that some progress is already being made, as Oakley himself indicates. I also agree with him that a force made up of individual volunteers may indeed take a very long time to emerge. I am very much aware that member states might object, as they have in the past, to a wholly independent UN force, but I hope that the suggestion of such a force might help to clarify in the minds of governments how the United Nations can be made to control conflict more effectively and expeditiously in the future.

Of course a small, immediately available, or permanent, UN force has to be seen in the context of all the other possible preventive measures. The key necessity is for the United Nations to be able to act earlier and more decisively to head off disasters. Robert Oakley’s idea of using military stockpiles left over from the cold war is a valuable one, as indeed is his idea—new to me—that if a small rapid deployment force does not secure the needed results and cooperation in a reasonable time, it may well be a signal for the United Nations to pull out rather than perpetuate an ongoing bad investment.

McGeorge Bundy also emphasizes the main problem now facing the United Nations, which is how to acquire the means to take early and effective action. He has made some very useful practical suggestions on how this might be achieved in the present circumstances.

Sadruddin Aga Khan sees the main obstacle to progress in the current state of mind of the Security Council, and especially its permanent members. I think it is certainly true that the Council needs, if it can ever find the time from dealing with day-to-day crises, to have a serious debate on such matters as criteria for intervention, rules of engagement, new possibilities for speedier and more effective action, and a number of other basic questions.

I fully agree with General Obasanjo that there should be a well-defined international process for dealing with conflicts, starting with a “peace watch” and preventive measures, which should be given the highest priority. Of course more forceful measures will be needed only if earlier preventive measures have failed to produce the desired result, as is the case in several current situations. General Obasanjo’s observations on such matters as recruitment, organization, and the inherent problems of a volunteer force are of great importance and interest.

I am grateful to Sir Anthony Parsons for stating so concisely and brilliantly the problems which will arise if some kind of rapid deployment peace enforcement force is not created. Nobody denies that there are a great number of obvious objections and difficulties which will have to be overcome. Parsons makes an irrefutable argument for the necessity of overcoming them.

Marion Dönhoff raises a number of important questions which certainly need to be discussed and resolved. In fact I mentioned some of them myself in my original article, in which I suggested that the force in question, unlike existing UN forces, should be trained as combat units, should mainly be used to deal, at an early stage, with conflicts within states, and that it should be responsible to the Secretary-General and subject to ultimate control by the Security Council, under arrangements that remain to be worked out. Dr. Dönhoff hits exactly on the main point in saying that what is needed is to find a way of preventing disputes and conflicts from degenerating into uncontrolled violence. I hope very much that the comments and suggestions which are now being published will contribute to this vital objective.

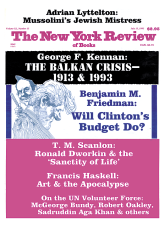

This Issue

July 15, 1993

-

*

Published by the Ford Foundation, New York, April 1993. See pp. 14–21.

↩