Written on the Body is the fifth novel by the British writer Jeanette Winterson. She published her first in 1985 when she was twenty-six. It was autobiographical and in some ways a more cheerful replay of The Way of All Flesh, with a mother and daughter instead of a father and son at loggerheads in a sectarian family. Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit won a prize and became a successful television play. And no wonder, because the story Winterson had to tell was piquant and extraordinary, and so was her manner of telling it.

The heroine of Oranges—called Jeanette—grows up in a lower-middle-class family in an industrial town in Lancashire. They belong to a revivalist church around which the whole household revolves. Everyone accepts that Jeanette has been chosen by the Lord to be a missionary. As a schoolgirl she is already in demand not only as a guitarist to accompany the robust hymns of the faithful, but also as a gospel teacher and preacher. So it comes as a shock to the congregation when they discover her having an affair with a recent convert called Melanie. Apart from the pastor most of the influential elders seem to be women, and they aren’t as hard on Jeanette as one might expect. Of course the devil who has got into her has to be exorcised, but after that ordeal is over the congregation is happy to have her back.

The exorcism doesn’t work, though, and Jeanette is in trouble again, with Melanie and then with Katy too. Her mother throws her out. Jeanette rents a cheap room and finds two jobs to help pay for it; one is driving an ice-cream van, the other laying out corpses and washing the hearse for a local undertaker. A competent girl, she can also be left to organize and serve the funeral lunches. When she finishes school she takes a full-time residential job in a mental hospital. Not her ideal choice, but “a room of my own, at least.” She gets another job, moves to another town, and tries going home on a visit. Her mother has gone into electronic evangelism and is far too busy to be angry anymore: she demonstrates her brand-new electronic organ to Jeanette, then bustles back to her transmitter: “This is Kindly Light calling Manchester, come in Manchester, this is Kindly Light.” The novel ends here. The real Winterson, the blurb tells us, went to Oxford to study English. Then she moved to London and became a full-time writer.

Not many writers have the luck to have such an entertaining adolescence. Or one that pitches them into the hot topic of sexual politics from such an eccentric springboard. The problems come into focus for Winterson when her mother says of a male homosexual: “Should have been a woman that one.” She realizes,

This was clearly not true. At that point I had no notion of sexual politics, but I knew that a homosexual is further away from a woman than a rhinoceros. Now that I do have a number of notions about sexual politics, this early observation holds good. There are shades of meaning, but a man is a man, wherever you find it. My mother has always given me problems because she is enlightened and reactionary at the same time. She didn’t believe in Determinism and Neglect, she believed that you made people and yourself what you wanted. Anyone could be saved and anyone could fall to the Devil, it was their choice. While some of our church forgave me on the admittedly dubious grounds that I couldn’t help it (they had read Havelock Ellis and knew about Inversion), my mother saw it as a wilful act on my part to sell my soul. At first, for me, it had been an accident. That accident had forced me to think more carefully about my own instincts and others’ attitudes. After the exorcism I had tried to replace my world with another just like it, but I couldn’t. I loved God and I loved the church, but I began to see that as more and more complicated.

The passage announces promising future preoccupations: sexual determination and personal freedom, and how to reconcile them.

There is also a propaganda element. “Oranges is a threatening novel,” she wrote in her introduction to the English paperback edition. “It exposes the sanctity of family life as something of a sham: it illustrates by example that what the church calls love is actually psychosis and it dares to suggest that what makes life difficult for homosexuals is not their perversity but other people’s. Worse, it does these things with such humour and lightness that those disposed not to agree find that they do.”

Of her subsequent novels, two, The Passion and Sexing the Cherry, are magic realist historical fantasies. The first is partly set in Venice during the Napoleonic Wars: the second in seventeenth-century London. Fairy tale characters and events are mixed up with historical ones and ultra-pungent descriptions of the daily life of the time. Even in Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit there were Arthurian insets, featuring sorcerers and the Holy Grail. But they are few and far between, and mostly the novel is a straightforward account of growing up homosexual.

Advertisement

The process has been described by David Bergman in Gaiety Transfigured: “Jewish children, for example, from infancy are brought up with a looming sense of their religious identity just as black children from birth develop a sense of racial identity, or baby girls soon find what it means to be female. But gay children—who have a keen sense of being different—often have nothing and no one to show them what the difference consists of, or how one might integrate that difference into a way of life.” The bit in italics (mine) has built-in possibilities for tragedy, of course: but for comedy too, and those have not been much exploited. Winterson has the oddball vision and guts to make the most of them. Her first novel is very funny, laid-back sometimes, more often cheekily aggressive. She bounced into the limelight squawking like a literary Donald Duck with Byronic leanings. Byron is one of Winterson’s heroes, she says.

This character is Byronically provocative, addicted to risk, driven by reckless perfectionism; and Byronically amorous too: a Don Juan with a roll call of past mistresses: Judith, Inge, Catherine, Bathsheba, Estelle, Jacqueline—the last still current though on the way out when the novel begins. It could be read as a sequel to Oranges, though not an immediate one: the narrator now seems to be about Winterson’s present age. When it appeared in London last year, the literary people read it as a roman à clef and joyfully identified the nameless narrator and his/her great new love, who is called Louise in the novel. The his/her ambiguity is a gimmick that works until the turning point of the story, with a scatter of teasing, misleading clues: the narrator dresses unisex in a “business suit” or “baggy shorts which in such weather look like a recruitment campaign for the Boy Scouts. But I’m not a Boy Scout and never was. I envy them: they know exactly what makes a Good Deed.” But once the lovers are separated, the narrator wears a body stocking and comes out: “I thought difference was rated to be the largest part of sexual attraction but there are so many things about us that are the same.”

The story is a traditional tale of adultery, renunciation, and reunion, but it hinges awkwardly on an unlikely piece of blackmail. Louise leaves her horrible husband and moves in with the narrator without telling her that she has leukemia. The horrible husband happens to be a distinguished cancer specialist. He alone can get Louise admitted to a Swiss cancer clinic, the only place in the world where she might be cured. But he won’t do it unless the narrator renounces her. Nobly (and against Louise’s wishes) she makes the sacrifice and disappears without leaving an address. Up to this point the story is almost excessively classic, an amalgam of Anna Karenina and La Dame aux camélias as told by the hero of Le Diable au corps. What follows is more adventurous, a series of meditations upon physical love: “The recognition of another person that is deeper than consciousness, lodged in the body more than held in the mind.” Each mediation dwells on a different system of the body—cells, bones, cavities—and is preceded by a quotation from a manual of anatomy. The meditations are intense, poetic, metaphysical, and sexy. They explore new areas of desire and worship and sometimes come out in Biblical rhythms, echoing, in particular, the Song of Solomon.

After the meditations, we find the narrator living in a tumble-down cottage in the North and working in a downmarket but aspiring wine bar with opportunities for comedy. The fat, middle-aged proprietress falls in love with her and pursues her with clumsy persistence. Still, she may be the novel’s true heroine: when she finds her suit is hopeless, she persuades the narrator that she should never have left Louise. The narrator rushes to London to find her, but the horrible husband has left his wife and all traces have gone cold. The narrator returns to her northern hovel to find fat Gail from the wine bar in possession and full of wisdom, “It’s as if Louise never existed,” says the narrator. “…Did I invent her?” “No, but you tried to,” says Gail. “She wasn’t yours for the making.” At that point Louise walks in, thinner but not bald, and the last paragraph pulls out all the stops:

Advertisement

This is where the story starts, in this threadbare room. The walls are exploding. The windows have turned into telescopes. Moon and stars are magnified in this room. The sun hangs over the mantelpiece. I stretch out my hands and reach the corners of the world. The world is bundled up in this room. Beyond the door, where the river is, where the roads are, we shall be. We can take the world with us when we go and sling the sun under your arm. Hurry now, it’s getting late. I don’t know if this is a happy ending but here we are let loose in open fields.

This apocalyptic high—and the earlier anatomical meditations too—remind one of Ingeborg Bachmann (the narrator is a professional translator, so she may know the Austrian writer’s work). Like Bachmann, Jeanette Winterson is given to making huge pronouncements, though hers are more exclusively concerned with personal relations and sexual behavior than with world affairs—except for occasional laments about the environment. Her concern for that goes with a Romantic brand of conservatism, distaste for technology, and a Samuel Palmer–like vision of the English landscape: “The sky is clear and hard, not a cloud, only stars and a drunken moon swinging on her back. There’s a line of ash trees by the picket fence that takes you out of man-made things into the deep country where the land’s not good for anything but sheep. I can hear the sheep munching invisibly over tussocks of grass thick as a pelt.”

The echoes of other writers in Winterson’s work may well be only in the reviewer’s mind. The way she uses words is peculiar to her alone. She employs, she says (again in the introduction to the paperback Oranges), “a very large vocabulary and a beguilingly straightforward syntax.” Her writing is like a wall of dry stones: each word a specially chosen rock, unique in color and shape, with no cement to hold them all together, no boring structural expedients or emplacements. The effect is stimulating, punchy, and, as she says, beguiling. She is a writer whose appeal rests very much on her tone of voice—which does not mean she has only one. She is a wonderfully funny mimic of speech, and a resourceful creator of new idioms. In Sexing the Cherry, for instance, the heroine is a giantess living in the Thames-side mud. She speaks a vernacular—invented of course—which one can accept as seventeenth-century colloquial. It is casual but poetic, with echoes (not overdone) of the Authorized Version, and it underpins the character’s appeal:

I was offered a job in a whore-house but I turned it down on account of my frailty of heart. Surely such toing and froing as must go on night and day weakens the heart and inclines it to love? Not directly, you understand, but indirectly, for lust without romantic matter must be wearisome after a time. I asked a girl at the Spitalfields house about it and she told me she hates her lovers-by-the-hour but still longs for someone to come in a coach and feed her on mince-pies.

But although one must assume that Written on the Body is a continuation of Oranges, the narrator’s voice and personality have changed—as they do in real life. The “humour and lightness” she herself found in her first novel (she is not a modest person: last year she nominated Written on the Body as best book of the year, and the most underrated as well) are less in evidence. The new persona is more plaintive and given to self-pity, more sententious and preachy. Winterson’s inbred missionary fervor is employed to put across the gospel of sexual freedom, but there is not much forgiveness. Louise’s husband gets metaphorically kicked in the balls, whereas Jeanette in Oranges takes her bossy mother in her stride with appealing forbearance. All this may be irrelevant to the literary merit of the new novel, but it makes it harder to like, which is a pity, because Winterson has a lot of talent.

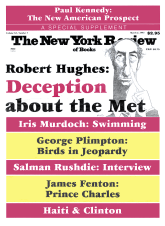

This Issue

March 4, 1993