Danny De Vito’s Hoffa is artfully constructed, masterfully played, and travels at speeds beyond the prescriptive norm. It weaves back and forth across the dividing line between truth and myth with the controlled recklessness of an over-the-road trucker making up time by breaching the peace of mind of drivers slower than himself. Jack Nicholson’s Jimmy Hoffa is magnificent, but it is not Jimmy Hoffa. Nicholson has caught and occasionally even come close to incarnating Hoffa’s tragedy. But he cannot define it for us because a misconception of the hero as an idealist keeps getting in his way.

De Vito’s tale, as told by David Mamet, begins with the fallen president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters sitting with his last loyal liege and waiting outside a Detroit roadhouse for a sitdown with a Cosa Nostra don. Now and then in these empty hours his mind runs back to past events, and one of them is re-created, returning us to Hoffa at his lonesome vigil, until we are borne on to the next reminiscence.

This recurring device is neatly contrived for packaging the goods and moving them down the road. It nonetheless pays an extortionate price in violations of the probabilities. The clock in the roadhouse has to run nearly six hours for Hoffa to wait for his unfulfilled rendezvous, with no occupation except to read about himself in Robert Kennedy’s The Enemy Within and to muse over old once-happy far-off places and battles long ago.

No one who knew Hoffa, however distantly and untrustingly, could imagine him, exhausted and desperate as he may then have been, idling through an afternoon on the diminishing chance that he might not have been stood up after all. Jimmy Hoffa would not have bided his time that long for the Lord God Jehovah Himself. To look at him carefully was soon enough to mark impatience as the motor of his nature. The late Edward Bennett Williams was Hoffa’s defense counsel in the 1950s and accomplished the prodigy of getting him acquitted after his client had been lured into paying a bribe for a peek into the files of the Senate Committee on Investigations.

On the night after the jury retired, Williams talked about Hoffa. “This guy is a jumper,” he said. “This time he jumped from the eighth floor. If he gets up and walks away, he’ll climb right back to the ninth floor and jump again. He’ll go on doing that until he gets to the thirty-second floor. He has a genius for improving a misdemeanor into a felony.”

Personages so wildly larger than life have doom woven into their very souls. Their reflections in the hours before they meet its final appointment have a character too sacred to admit memories other than absolutely authentic ones. No tragic hero of such size can be taken to be true to himself unless everything he remembers is true to the elementary facts of personal history; and De Vito, Mamet, and even Nicholson have damagingly flawed their portrait, because so many of the happenings their Hoffa recalls never happened to Jimmy Hoffa at all.

He never captained a war upon a great capital establishment in numbers so immense and tempers so pitiless that seven or eight pickets died from the bullets of policemen and the clubs of strikebreakers. Hoffa’s evocation of this brutal passage is exhilaratingly spectacular as agitprop; but its real scenes took place far from any experiences of Jimmy Hoffa’s, and happened not in Detroit, but outside the South Chicago Republic Steel Mill where police slaughtered seven strikers and reddened the annals of the old CIO with the blood of the martyrs of the 1937 Memorial Day massacre.

Such epical pitches of the class war were not for Hoffa or for an AFL Teamsters Union that was too strategically well placed to need them. All powers for binding or loosing the shipment of commodities belonged to the unionized driver; and the business agents who booked the drivers’ trips were free to dictate the drivers’ side in any strike. The union manager could help either the union by cutting off deliveries or the employer by letting them through the picket lines. He was the gatekeeper who could choose as he pleased between supporting his class or collecting a fee from its enemies. The quarrels of the barricade were outside the jurisdiction of the individual teamster; his will could hardly express itself except as a translation of the desires of his union business agent, whose option it was either to gratify his fraternal sentiments for the strikers or to satisfy his greed with a payoff from the employers.

These were enormous powers; and traditional teamsterism had widely distributed them among local business agents, each of whom exercised his command over a narrow regional fief jealously guarded against intrusion from any National Teamster president. Hoffa early understood that sovereignty in a union like his was more usefully served by taming his local business agents than by battling less frequently resistant trucking corporations. His only memorable wars were of the fratricidal sort; and he was always more agreeable in bargaining union contracts than he ever was in quarrels with rival teamster bravoes.

Advertisement

His major achievement as an organizer was to convert the Teamsters Union from a confederacy of autonomous regional barons to a monarchical structure obedient to every command from national headquarters. The construction of this monument was not quite complete when he went to jail; and the endemically anarchic impulses of Teamster habit soon enough wrecked its foundations. Every professional went back into business for himself delighted to be free of Hoffa’s overbearing interferences and unable to regard his return from prison as other than the gravest of perils to the independence of subordinates, who, having wept to see him go, found themselves rejoicing to have him gone.

If he had enjoyed enough time to harden the union into his instrument from top to bottom, it is hard to conceive what he would have done with it. There is small likelihood that he would have used it to bring low the grand proprietors of capitalist enterprise, for whom he had a respect that came rather close to kindred feeling.

Hoffa’s disabling misapprehension is indeed to think of Jimmy Hoffa as a social radical rather than the antisocial rebel he really was. His genuine hatreds were reserved not for those who owned the country but for those who wrote and enforced its laws. He cherished the Teamster rank and file and, in the main, it adored him; but his services did less to forge the bond than to reinforce a shared alienation that expressed itself in his lawless contempt for society’s speed limits. He was out to own the road and so is the interstate truck driver.

And thus he did not go to prison, as Hoffa tells us, for one of those illicit collaborations with organized crime that the investigators incessantly tried and regularly failed to nail him with. He was instead found guilty of trying to bribe a juror to avoid conviction for a puny flier at real estate fraud. He had thus ruined himself with an incautious defiance of the behavioral codes of organized society, making inevitable the misdemeanant’s improvement into the convicted felon. And he had acted in accordance with the one consistently heroic side of his nature, which also happens to be the one that Hoffa almost insistently overlooks.

But then we may suppose that Hollywood was especially drawn to Hoffa because they have in common the illusion of an America governed by the Mafia. Hoffa had indeed an outsized reverence for the authority of organized crime, because he had grown up unionizing laundries, dry-cleaning establishments, and like appurtenances of its petty domain. When he set out to displace the Teamster Old Guard, it therefore suited his acquired predisposition to recruit an unquestionably faithful New Guard from the gangster cadres.

I once pressed him to explain why he had put so many ex-felons, if not all else but ex-felons, in charge of so many Teamster divisions. “The best guy to work for you is the guy with the rap sheet,” he replied. “No one else will hire him. He’s got to be loyal to you.” I was never privy to many other of his philosophical observations; and those Mamet has put in Nicholson’s mouth sound to me less plausible as Hoffa’s actual style in discourse than as evidence of this playwright’s wonderful talent for making his characters say far better things than they could ever have thought to say in real life.

I myself can certify just that one sample of Hoffa’s table talk, and it is striking for having turned out to be dead wrong. The felons he trusted to be his servants because they had no alternative master were the quickest to abandon him in his fall; he was on ice in Lewisburg, and his seat had been usurped by successors glad to keep such felons in office and be rewarded by their availability for employment as his assassins.

Those who ran the Teamsters Union and exploited its members had cast the real Jimmy Hoffa away, and all his hopes for reasserting command now depended on the rank and file. He must have thought of the ordinary Teamsters and their cause with a tenderness long forgotten and have approached the hour of his end with livelier stirrings of being both victim of and warrior against class oppression than he had entertained for a long time.

Advertisement

So then the mind that waited in the car would be more persuasively imagined as at last settling into the key of “Had I but served my people with half the zeal I tried to serve myself, I would not have been left thus in my decrepitude naked unto mine enemies.” That would have been the moment of recognition appropriate for destiny’s disposal of the hero this awful man in some way was. But it would also have been the appropriately telling note of high tragedy that seems always too troublesome for Hollywood to bring off. What we get instead is a most ingenious murder and no catharsis, however splendid and bloody a go Jack Nicholson has had at giving it to us.

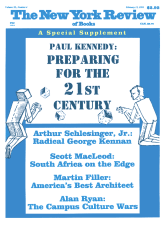

This Issue

February 11, 1993