A French friend said to me two years ago that there were two ways for Poland to emerge from its appalling crisis. The first would be through common sense: a miracle would happen and angels would descend to free Poland from communism. The second would be through a miracle: the Poles—including both the Communists and the opposition—would come to an understanding with one another. This miracle—something that seemed to me utterly impossible—actually occurred in my country. The prisoners and their guards sat down at a table and began to negotiate. The result is that communism has ceased to exist in Poland today. This was by no means a foregone conclusion—things could have turned out quite differently. The way was smoothed by a specifically Polish feature of the situation: the combination of President Jaruzelski, who, as the man who had imposed martial law, could ease Soviet fears; and Prime Minister Mazowiecki, who simultaneously made it clear both to the Poles and to the West that there was a strong will for change.

In the meantime, however, many people in Poland have begun to believe that we are going too slowly, and that it is time to break the agreements that were made with the old ruling power. I contend that we should think twice before disturbing this fragile equilibrium.

There are two ways to emerge from dictatorship. The first is the Spanish model. It begins with a pragmatic compromise between reformers from the government and the democratic opposition. This enables the members of the ancien régime to reconcile themselves to the new situation; they have a chance to survive and can hope to find a new place in society; they will even become defenders of democratization because they see that they can gain advantages from it. The second way was taken in Germany and France: “denazification,” or expiation of collaboration. But that way also meant revenge, the settling of accounts, retribution. And when I consider where such an approach can lead, once again I see two variants. First there is the Iranian model: one dictatorship is supplanted by another; the ideology, language, and symbols are new, but a dictatorship is ruling once again. This is the case precisely because democracy is the child of compromise and violence the child of retribution.

Second, there is the situation that gives rise to the “Kabul syndrome.” In Afghanistan a full year after the withdrawal of Soviet forces the Communists continue to rule. They have no choice because the mujaheddin have not given them a chance to adapt to the new circumstances. The Communists are defending themselves with such bitterness because only one fate awaits them if they lose. In Poland, on the other hand, the Communists can simply give up—an outcome unparalleled in history.

Communism has suffered many defeats in Poland over the years; now, however, it has capitulated. What we are seeing now is the retreat from the centers of power by people who are defending their positions, their money, and their personal security—but who no longer believe in the restoration of communism. Communism is dead; but what continues to exist is the army and the security apparatus—groups who know that they have lost, who are frustrated and frightened, who feel threatened, and who continue to have weapons at their disposal. This is a very dangerous combination. Military conspiracies such as those of the OAS in France—by small groups that act desperately—can also occur in Poland. This situation compels us to make compromises, and it rules out confrontation.

The greatest threat to democracy today is no longer communism, either as a political movement or as an ideology. The threat grows instead from a combination of chauvinism, xenophobia, populism, and authoritarianism, all of them connected with the sense of frustration typical of great social upheavals. This is the perspective from which we must view the old conflicts that are now flaring up again in Central and Eastern Europe. The Soviet Union provides an especially vivid illustration of the two types of anticommunism now locked in struggle with each other. One, as represented by Sakharov, is liberal, pluralistic, and European; the other, advocated by Igor Shafarevich, is xenophobic, authoritarian, turned toward the past and toward restoring the life of the past.*

This second type of anticommunism is distinguished most tellingly by its reluctance to do away with the figure of Stalin, because he was the founder of the Great Russian empire. Dictatorship, according to this view, should not be abolished but should rather be continued in a different form. Collective property will also continue to exist, with the collective farms being replaced by more traditional communes—arteli. The members of this movement do not see their main enemy in the Communists, but rather in those who aim to create democratic institutions and an open, civil society. What they share with the old Stalinists is the struggle against the influence of Europe, which in their eyes embodies greed, godlessness, and the decline of morals. Russia must be protected against this by the creation of an anti-European bloc within Russian culture.

Advertisement

If Russian history is viewed from this perspective, it is merely the next logical step to reject communism not because it was a dictatorship, but because it was not Russian. Communism was not invented in Russia; Marx was not born there, nor was the Communist Manifesto published there—it was decadent Western civilization that infected Russia with communism. The Bolshevist Revolution was not the work of Russians, but of foreigners—the Jew Trotsky, the Pole Dzerzhinsky, the Georgian Stalin, Ukrainians, Latvians, and Chinese. The Russians were innocent.

This line of thinking can be observed most clearly in Russia. But it is the manifestation of a psychological mechanism that has been set off in all of the countries in which the Communists held power, including Poland. Here as well there are certain people who hold aliens and foreigners—Russians, Germans, Jews, cosmopolites, Freemasons—accountable for bringing communism to Poland. The most important conflict in Polish culture today is being fought between those who see the future of Poland as part of Europe and those characterized by the Polish sociologist Jerzy Szacki as “natiocentric”—although the first do not by any means reject national values and traditions and the latter are not necessarily chauvinist. In any case, these two approaches today divide the Polish intelligentsia; they cut across all political lines and can be found among adherents of the ancien régime as well as within Solidarity and the Catholic Church.

When considering the fate of Eastern and Central Europe, I often ask myself whether chauvinism will once again gain the upper hand. Whether the victors will be those in Berlin and Dresden who screamed Polen raus, or wrote those words on walls, in November and December of last year; those in Bulgaria who deny Muslims the right to their own names; those in Transylvania who deny Hungarians the right to their own schools; those in Poland who promote anti-Semitism and a country without Jews. These people could be victorious. They have their chance because we do not know what will flow into the great vacuum left behind by the death of communism. And also because the democratic idea and Christian thinking are complicated: they do not pretend to give simple answers to the difficult questions of the age.

So the chauvinistic approach could win. What we have learned during the past year (the most unusual in the fortyfour years of my life) is that there is no determinism in history, that our history depends far more on ourselves, on our will and our decisions, than any of us thought. If we want to stand up to the danger, we have to know where it comes from, and we have to call it by its name. And if there are reasons for assuming that this danger is deeply rooted in certain social attitudes that can only promise new injustice and new oppression, then it is our duty as inheritors of European culture to fight against those attitudes—in the name of all those values of Judeo-Christian culture that were defended for centuries at the cost of great sacrifices.

Just as France showed two faces during the Dreyfus trial, two faces are now being shown in Eastern and Central Europe. Even then, however, the forces of good and evil were not neatly divided along the lines that separated leftist republicans from rightist national conservatives. It is never that simple. For that reason we must always be prepared to understand and acknowledge the values of our opponents, even those we are fighting against. Only then are we truly Europeans.

—translated by Mariusz Matusiak and Christian Caryl

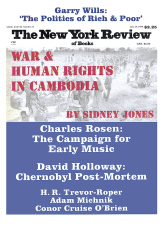

This Issue

July 19, 1990

-

*

Igor Shafarevich is a well-known Soviet mathematician and, in the 1970s, he became a prominent ally of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and defender of human rights in the USSR. Author of Russophobia, a Slavophile history of Russia, Shafarevich has recently written in support of authoritarian, anti-Western, and anti-Semitic policies.

↩