In response to:

The Kennedys in the King Years from the November 10, 1988 issue

To the Editors:

It was a keen disappointment, to say the least, to see a writer of Garry Wills’s stature take Robert Kennedy’s quotes out of context to make Mr. Wills’s points in his article “The Kennedys in the King Years” [NYR, November 10, 1988]. But he did. The quotes Mr. Wills took from Robert Kennedy In His Own Words: The Unpublished Recollections of the Kennedy Years, which I co-edited, served Mr. Wills’s purposes and distorted Robert Kennedy’s statements. It was careless, pick-and-choose journalism that does not do Mr. Wills any credit.

And there was an error that was not insignificant and that indicated Mr. Wills’s checking for his article was less than vigorous. He wrote that Robert Kennedy tried to protect James Meredith at the University of Mississippi with unarmed deputy United States marshals.

On the night of September 30, 1962, about 300 marshals encircled the Lyceum on the Ole Miss campus where Meredith was to register the next morning. A smaller detachment guarded Meredith at Baxter Hall about a mile from the Lyceum. The marshals at the Lyceum withstood a series of furious assaults by a mob of 2,000 or so men, many of whom had driven long distances and had brought their shotguns and rifles “to stand with Ross” (Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett).

More than one-third of the marshals—160 in all—were injured; 28 were wounded by gunfire.

All the marshals carried revolvers but never used them. Several times during the battle they asked for permission to return the fire. Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach at the command post in the Lyceum relayed their requests over an open telephone to the White House, but President Kennedy and Robert Kennedy each time said “No” unless it was necessary to save Meredith.

Baxter Hall never was attacked, and the marshals at the Lyceum, though embattled and furious at seeing their comrades shot down, held their fire. They were loyal men, well trained in their respective fields, but they had been assembled hurriedly from all sections of the country and there had not been time to organize them into well-disciplined units—yet they obeyed.

One would remember them in the racial riots and campus demonstrations in the latter half of the 1960s and early 1970s—at Kent State and Jackson State and Peoples Park in Berkeley and at many other places—when lawmen with far, far less provocation and injury than the marshals endured, gunned unarmed people down. And when public officials defended those actions, one would remember John and Robert Kennedy, the responsibility they shouldered that night and their restraint and judgment.

I know all the marshals were armed because I was there.

Edwin O. Guthman

University of Southern California

Los Angeles, California

Garry Wills replies:

I wrote that Robert Kennedy “tried to protect Meredith against angry crowds with unarmed marshals, since JFK had criticized Eisenhower for sending troops into Little Rock.” Kennedy failed to use unarmed marshals, as he failed to keep troops out of the South; but his political fear from the outset was to have federal representatives shooting at southerners. As Anthony Lewis put it:

LEWIS:…Your real fear, and it was a very real fear, was that there would come a point at which United States troops would be facing Mississippi troops in the form of sheriffs and police and other Mississippi law enforcement officers shooting at each other [Robert Kennedy in His Own Words, p. 160].

Kennedy was even more concerned about guns in the hands of marshals. Burke Marshall noted that many of the men pressed into service late and hurriedly (because the Kennedys tried to get along without them) had no riot training (Robert Kennedy in His Own Words, p. 94); Robert Kennedy added “you didn’t know how they were going to react” (Robert Kennedy in His Own Words, p. 95). Governor Ross Barnett tried to make federal marshals not only carry but draw their guns (Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters, p. 636), a ploy Kennedy was resisting. When the marshals were hastily assembled, some of them—security guards and others—came already armed (they were not issued guns), and Kennedy was insistent that they not use these unwanted weapons:

KENNEDY: [Nicholas Katzenbach] did call up and ask if they could use live ammunition because people were getting so close. They were coming in. President Kennedy, who heard my conversation, said that they weren’t to fire under any—

LEWIS: They were not to fire?

KENNEDY: They were not to fire under any conditions.

LEWIS: That’s something that I had not known before. They were not to fire if they were being overwhelmed?

KENNEDY: Yes.

LEWIS: That’s a tough order to carry out, isn’t it? [Robert Kennedy in His Own Words, p. 162].

It certainly was, and the marshals deserve all the credit Mr. Guthman gives them. But they were put in that situation, as I noted in my review, by the Kennedys’ reluctance not only to use force but to get involved in the civil rights movement at all—a reluctance that comes through not only in the quotes I used in the review, but in the entire context of Kennedy’s interviews, where not alienating the South from his brother’s presidency (and from his own future presidential campaign) is the foremost consideration, repeatedly asserted against Mr. Lewis’s attempts to elicit a different assessment of what mattered to the Kennedys at the time. For instance, I quoted Kennedy’s reference to Harris Wofford as “in some areas a slight madman.” What was the context?

I didn’t want to have someone in the Civil Rights Division who was dealing not from fact but was dealing from emotion and who wasn’t going to give what was in the best interest of President Kennedy—what he was trying to accomplish for the country—but advice which the particular individual felt was in the interest of a Negro or a group of Negroes or a group of those who were interested in civil rights. I wanted advice and ideas from somebody who had the same interests and motivation that I did…. That was the reason I looked outside of Harris Wofford [Robert Kennedy in His Own Words, pp. 78–79].

Not putting the Kennedys first made a civil rights advocate slightly mad.

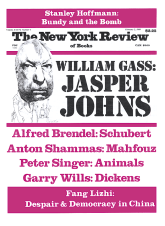

This Issue

February 2, 1989