How Chopin played the piano, though a puzzling question, is not beyond all conjecture. For almost the last hundred years, we have been given an image of the past by records and tapes, but that specious patent from oblivion is generally misleading and always distorted—and subtle distortions are the most difficult to compensate for (no recording will adjust to the acoustics of your living room as a live performer would). Before recording, we have only uncertain memories, twisted by time and prejudice, inaccurately set down, and letters or reviews, dusty, crumbling, and not to be trusted.

If we still try to raise the dead, to conjure up some ghostly idea of Chopin as a pianist, it can only be because of the lasting monuments in which he subsists, the productions in which he lives—his music. We feel that knowing the way he performed would help us give meaning to the scratches he made on paper. The assumption is not wrong, but it has its dangers: the composer and the performer are not exactly the same man, even if they inhabit the same body, and the former often outstrips the latter in originality and daring. The performer understands best about a piece of music only what his limited technique and manner can deal with most effectively, and many composers have been enlightened as well as surprised by a kind of performance that they had not foreseen. The notes often understand one another better than the composer understands them—this was a paradox familiar to romantic aesthetics. Still, a knowledge of contemporary performance is never entirely irrelevant, and the composer’s performance is the least irrelevant of all.

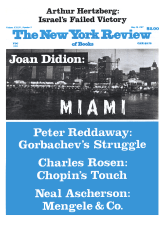

Fryderyk Chopin: Pianist from Warsaw by William G. Atwood is not about Chopin as a composer: his music is mentioned only in passing. Nor is it about the way Chopin played the piano, except incidentally: the most reliable witnesses to that were Chopin’s pupils, and they are not called up here for their testimony on the subject. What interests Atwood is the concert career of Chopin, and he deals almost entirely with that and the way the career fitted into Chopin’s sentimental life, in particular his affair with George Sand, a subject on which Atwood has written a previous book. Atwood is by profession a physician, and one might have thought that the details of Chopin’s many illnesses would interest him, but these, too, appear only incidentally—when he has a headache after playing a concert, for example.

I ought not to complain that Atwood did not set out to write a different book, even if the relation of Chopin as a pianist to his progress as a composer would clearly have been more rewarding. It is, however, only fair to point out that Chopin’s concert career is not a particularly interesting subject, since he did not, in fact, have much of a career. He made very little money by public appearances—or by composing, for that matter, and lived largely by teaching. He grew terrified of public concerts, and after some initial successes when he was young his performances became exceedingly rare, with none at all in the years between 1843 and 1847. After one recital in Paris in 1848, he refused to give a second: “The first has already been such an aggravation,” he wrote. After the Revolution of 1848, he attempted to put his finances on a better footing with a series of concerts in Scotland and England, but succeeded largely in hastening his death from tuberculosis.

The intrinsic lack of interest of Chopin’s concert career as such has not prevented Atwood from writing an interesting book almost inadvertently and unsystematically on a different subject: the European concert life of the 1830s and 1840s. We do not learn much about Chopin’s musical life—how could we when his work as a composer is only glanced at tangentially—but there is a lot of gossip about his love affairs; above all, there is a lot of material about how concerts were organized, tickets sold, artists engaged, and so forth. Best of all, the programs of many concerts are given in full. All this material is presented with an attempt to relate it to the fashionable world of Paris and elsewhere and with some understanding of the social pressures exerted upon the performance of music—the fetes at which one had to play, the duchesses who helped sell subscriptions to recitals. And we learn about M. Pape who invented a combined piano and oven, so that one could bake while making music.

The greatest weakness of the book is its uncritical reliance on newspaper reviews, which provide most of Atwood’s material. He prints a large selection of these reviews as an appendix, and they are, predictably, not enlightening. When Atwood refers to them, he does not seem to notice the difference between the ordinary run-of-the-mill journalist or a critic like the one in the Athenaeum of London of July 1, 1848, who gives a brilliant description of Chopin’s idiosyncratic technique—largely because he already knew what would happen. (He concludes his account: “This we have always fancied while reading M. Chopin’s works:—we are now sure of it after hearing him perform them himself.”)

Advertisement

It is not generally realized, I think, to what an extent we hear what we expect and, above all, what we want to hear—how a fixed opinion can make us deaf to what is actually going on. The belief in Toscanini’s fast tempi, for example, was so firmly established that on the not infrequent occasions when his tempi were abnormally slow, no one seemed to notice and critics would still write about how fast the performance was.* For this reason, I am suspicious when I read the accounts of Chopin’s inability to play loud. It is certain that Chopin did not assault the keyboard as consistently as Liszt (although there are moments in his music—the last page of the Scherzo in B minor, for example—when he demands a brutal violence rarely encountered in Liszt); we must remember, too, that Chopin preferred to perform on the Pleyel instruments, considerably softer than the metal-framed Erards used by Liszt.

The solid wall of reports on Chopin’s unremitting delicacy was breached on a few occasions, once by the London Examiner, where the power of Chopin’s fortes was remarked by a critic—perhaps one too ignorant to have heard that Chopin always played pianissimo. A more interesting report is found in a note from Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger’s volume, Chopin: Pianist and Teacher as Seen by his Pupils.

Stephen Heller…”remembered hearing [Chopin] play a duet with Moscheles (the [same Grande Sonata] of which Chopin was so fond), and on this occasion the Polish pianist, who insisted on playing the bass, drowned the treble of his partner, a virtuoso well known for his vigor and brilliancy.”

Eigeldinger’s book is truly a book about the way Chopin played the piano, and about the way he interpreted his own music. It would be the best book on the subject if it were a book at all—it is more like a magpie’s hoard of documents, letters, notes, remembered conversation, gossip, and whatever could be found that pertains to Chopin’s pianism. Anyone interested in Chopin will be grateful to Eigeldinger. His book was originally published in French in 1970, enlarged in 1979, and now made available in English, with considerable improvements.

It must be admitted that the way Eigeldinger has organized his work makes it almost impossible to read: going through it is like mining, but the excavation is certain to be rewarding. The main body of the volume is in two parts: “Technique and Style”; and “Interpretation of Chopin’s Works.” Under “Technique and Style,” we have a collection of what Chopin’s pupils remembered his telling them on such subjects as “makes of piano,” “flexibility of the wrist and hand,” “legato and contabile,” “rubato and ornamentation,” “simplicity and poise as an ideal in playing,” “use of the pedal”; it finishes with a list of the repertoire studied by each student with Chopin. There are many grains of wheat and a great deal more chaff in this section. Much of what the pupils remembered consisted of the ordinary platitudes that every teacher tells his students: “‘Caress the key, never bash it’ Chopin would say,” or “He recommended that the fingers should fall freely and lightly.”

The descriptions of his playing are often similarly banal, or, worse, bathetic: “He always made the melody undulate like a skiff borne on the breast of a powerful wave,” wrote Liszt (or his mistress, the Princess Sayne-Wittgenstein, who often helped him produce his literary works). Chopin’s pupil and editor Karol Mikuli declared: “For all the warmth of Chopin’s temperament, his playing was always measured, chaste, distinguished and at times even severely reserved.” Of course. There is hardly any important pianist about whom this has not been said, even Liszt—although in his case the severe reserve must have been a little less frequent.

There are, however, much more illuminating nuggets of information:

[In Chopin’s works] when huge slurs extend over entire musical periods, they indicate this spianato playing, without nuances or discontinuities in the rhythm—impossible for those whose hands are not graced with perfect suppleness.

This was reported by Saint-Saëns as having come from Pauline Viardot, a famous operatic diva as well as a pianist, and a close friend of George Sand. Eigeldinger adds a note to explain spianato:

Term signifying levelled, and therefore equal, smooth, simple. This idea derives from bel canto, especially Bellini’s, according to Blaze de Bury (p. 112): “After the vivid and brilliant graces, the glittering colours and the sometimes overloaded ornamentation of Rossini’s method, the composer of Norma and I Puritani introduced a new style of tender cantilena, moving and palpitating—in short, spianato singing, as it is called in Italy, in all the eloquence of its expression.” The description applies admirably to the only work by Chopin bearing this indication, the Andante spianato op. 22 (tranquillo, ♩. = 69, according to the OFE). This type of playing is equally appropriate to other works characterized by a similarly tranquil type of respiration, such as the outer sections of the Nocturnes op. 15/1 and 27/1, of the Prelude op. 28/15, and so on.

Before Chopin, Paganini had already brought these vocal concepts to instrumental music: in 1829 he performed in Leipzig (and probably in Warsaw) a Cantabile spianato e Polacca brillante—a combination which surely has some bearing on the curious juxtaposition of the two pieces comprising Chopin’s op. 22

This illustrates the use and the dangers of Eigeldinger’s compilation. The explanation of spianato from the nineteenth-century musicologist is excellent (much better than the one in the New Grove), and brings out the importance of Italian opera in the formation of Chopin’s style. But these “huge slurs” extending “over entire musical periods” are found frequently in Chopin’s work, much too frequently, in fact, to permit Viardot’s generalization. They often extend over periods full of nuances and even, oddly enough, of discontinuities. It is clear, however, that the remark of Viardot is a stimulus to rethink many passages of Chopin, and it is clear that it applies only too often—too often for the majority of editions which break up these slurs into a multitude of short phrases.

Advertisement

The section called “Interpretation of Chopin’s Works” is on the surface more systematic: it arranges the works alphabetically by genre and chronologically within each genre, and prints a large selection of the comments on each work by Chopin’s pupils, friends, and colleagues. This rounds off the main body of Eigeldinger’s volume, but it is followed by seventy pages of notes to the foregoing, which consist of whatever Eigeldinger had neglected to put in, long quotations from his readings on Chopin, and general discussion, including the note on spianato I have mentioned. In these pages the author’s comments are consistently intelligent and contain some of the most interesting passages of the book. It is, however, often hard to rediscover passages that one remembers as particularly stimulating since comments, quotations, and discussion are mingled in no order with brief biographies of the different writers who are being quoted.

A list of Chopin’s students with brief biographies follow, succeeded by four appendices, of which the most interesting is the third, which gives the fingerings and annotations from the Chopin scores of pupils and associates. This is by no means exhaustive, and these sources are still not fully made use of in editions of Chopin’s music. They must be used with caution, however; an indication for one pupil does not imply that he wished everyone to use the given fingering. It has been remarked before, as well, that Chopin’s change of the tempo mark “Allegro” to “Largo” in his pupil Jane Stirling’s copy of the Prelude in E flat minor, Opus 28, probably meant only that Miss Stirling was playing too fast or making a mess of the piece and indicates Chopin’s exasperation.

As a pianist, Chopin was largely self-taught (his only teachers were a composer and a violinist); he also did not like to practice, as letters from his father tell us. He nevertheless developed into one of the most remarkable pianists of his day, and one of the most innovative as well. Chopin’s most idiosyncratic fingerings are oddly similar: the first is the realization of a soft, chromatic line entirely with the fourth and fifth fingers (or with the third, fourth, and fifth in more complicated passages); the other is the execution of a series of melodic notes entirely with the thumb, or with the third finger alone, sliding from key to key. In addition, he often played parts of delicate melodies with the fifth finger alone. These fingerings are found very early in his work—in the F minor concerto, for example, finished when he was eighteen.

These innovations put Chopin in direct opposition to the reigning contemporary piano pedagogy, the ideal of which was to make all fingers equally powerful and nimble. Chopin insisted that each finger had a fundamentally different character, and that the performer should try to exploit that difference (this is the most interesting point he makes in a series of unfinished notes for a piano method that Eigeldinger prints in an appendix). Delicate passages are played by the weakest fingers; the more emphatic notes of singing, lyrical melodies by strong fingers, often by one finger alone. This sense of the different character of each finger reveals something of the nature of Chopin’s musical thought: what interested him were subtle gradations of color, inflections of phrasing, and it was what he expected from performers.

This conception of technique places contrast of touch at the center of musical interpretation, and it was upon this that Chopin’s style was based. His idea of tone color is pure keyboard writing: he achieves by touch alone the contrast of timbres that other composers achieve by the use of different instruments. For this reason, Chopin’s tone color is as abstract as pitch or rhythm: it is based on the relationship between different kinds of texture realized with the neutral sound of the piano—neutral in that it is relatively uniform from top to bottom, or, better, in that changes of tone color from bass to treble are produced without a perceptible break. The ideal piano—for which every composer writes, not for the imperfect instrument at home—provides a continuum of sound, and the Romantic composer often requires a use of the pedal, which blends the different registers and ensures the partial realization of the continuum on our imperfect instruments; the real differences in timbre between high and low notes will be glossed over.

This use of balance and contrast makes the Etudes supremely difficult—this and the problem of endurance. No doubt the heavier action of the twentieth-century concert grand has made these pieces even harder to play than they were during Chopin’s lifetime, but they were a challenge from the beginning—too great a challenge in some cases, it is said, for Chopin himself, who exceptionally preferred Liszt’s execution of these works to his own.

The challenge comes from Chopin’s ruthlessness: he makes no concession. Like the Preludes of The Well-Tempered Keyboard which served as Chopin’s models, most of the Etudes develop the initial motif without pause until the end. The Etudes generally begin easily enough—at least the opening bars fit the hand extremely well. With the increase of tension and dissonance, the figuration quickly becomes almost unbearably awkward to play. The positions into which the hands are forced are like a gesture of exasperated despair. It would seem as if the awkwardness is itself an expression of emotional tensions. Perhaps this lies behind Rachmaninoff’s reported reaction to Alfred Cortot’s recording of the Etudes, almost the cruelest observation ever made by one pianist against another: “Whenever it gets difficult, Cortot adds a little feeling.”

There is no question that the difficulty in a Chopin Etude generally corresponds to the degree of emotional tension—although this does not mean that slowing down is the most satisfactory way of interpreting such passages. It does imply an intimate relationship between virtuosity and emotional force in the mature works of Chopin. The performer literally feels the sentiment in the muscles of his hand. This is another reason why Chopin often wanted the most delicate passages played with the fifth finger alone, the most powerful cantabile with the thumbs. There is in his music an identity of physical realization and emotional content.

Chopin’s interest in tone color can only be understood in the light of his equal interest in counterpoint and his lifelong study of Bach. He learned The Well-Tempered Keyboard as a child, and he never ceased to play it and teach it. It was the only music he took with him to Majorca on his famous stay there with George Sand; he warmed up for concerts by playing through several of the preludes and fugues. Although he was never tempted by the strict fugue to write one except as an academic exercise, he was the greatest master of counterpoint since Mozart. The sense of the movement of independent voices informs his work from the beginning of his career, and is paradoxically most marked in the Mazurkas, where the popular folk element is also at its most powerful. The late Mazurkas often imitate fugal writing, and the last published Mazurka even has an elaborate canon at the end.

This combination of tone color and contrapuntal line explains a curious entry in Delacroix’s Diary. The painter was a very close friend of Chopin, and a few years after the composer’s death, he noted:

My dear little Chopin used to protest strongly against the school which derives a part of the charm of music from the sonority. He spoke as a pianist.

This may seem odd at first sight because so much of Chopin’s genius comes from his exploitation of piano sonority. The observation worried Delacroix considerably; he wrote a long commentary on it, and then copied the whole page out into the diary again sometime later with considerable revision. Delacroix’s uneasiness springs from his role as leader of the colorist school in the nineteenth-century war between drawing and color. The opposition is largely a false one, as Delacroix himself knew, and as Baudelaire recognized when he placed Delacroix along with Daumier and Ingres as one of the three great draftsmen of the age.

The fusion of color and line was Delacroix’s great achievement, and it was equally essential to Chopin’s genius. He was as great a draftsman as Delacroix. The changes of color in his music—contrasts of texture, spacing, and register—are all governed by a sense of line unequalled by any of his contemporaries. It was what enabled him to achieve a synthesis of different styles—with the piano alone, to combine the lyric melody of Italian opera with the polyphonic richness of Johann Sebastian Bach. Even the virtuoso glitter of early-nineteenth-century salon music is an important element, although this is refined almost beyond recognition in the later works.

This Issue

May 28, 1987

-

*

The timings at Bayreuth record that Toscanini’s Parsifal is the slowest in the history of the house, astonishingly slower than Knappertsbusch’s, whose performances seemed to drag on forever. A good many of Toscanini’s performances of Brahms’s symphonies (except for the First) and much of his Falstaff are equally slow. Joseph Horowitz’s stimulating and instructive book, Understanding Toscanini, passes over all this in silence and remarks only on the performances that were rushed, as does Robert Craft’s review in these pages (NYR, April 9), bolstered by a quotation from one of Virgil Thomson’s notorious attacks on Toscanini. Thomson was the finest music critic of this century, but his writing on Toscanini must be understood in the light of his sedulous promotion of Eugene Ormandy: he even declared Ormandy’s interpretation of the Verdi Requiem the finest ever given (Ormandy was a good musician, but he never gave a performance of anything that was better than everyone else’s).

↩