Mark Girouard has written a book of great vitality about the way people have lived in Western or Western-type cities from the Dark Ages to the twentieth century, and about what those cities have been like. Unlike most historians of “urbanism,” who tend to organize their work around a theory of society and technology, Girouard denies having a theory or message. He writes simply, his judgments are modestly expressed, he eschews enthusiasm, pretension, and jargon. It is refreshing to find a learned book that divides town plans into the two categories of “plain” and “fancy.” Cities and People is a straightforward, descriptive account of the history and the social setting of the Western city, viewed in a traditional, chronological perspective. It is a remarkable achievement by a writer whose earlier work, with the exception of an essay on the Victorian vogue for chivalry, has been mostly concentrated on the history of the English country house. Girouard has been admired for his powers of synthesis. The present book shows him to be a writer of formidable range.

Girouard begins his book by explaining how the cities of the Middle Ages came into being and what they looked like. He sees the merchant oligarchs who dominate this scene somewhat conventionally, as the only leaders of social progress, but he is by no means without insight into medieval life, and he makes clear in one chapter how differently medieval society was organized from our own, when it was almost all in one way or another merged in the Church. The center of the book, “The City Triumphant,” is an account of what Girouard sees as the great period of the Western city. Using late sixteenth-century Rome as the model and point of departure, and concentrating on Paris and Amsterdam, he takes the big capital cities of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as his subject. Throughout he emphasizes that a “Renaissance” tradition of architecture and town planning endured in Europe until it was overtaken by the new functional needs of industrialism. The most original chapter here, “The City as Export,” brilliantly evokes the colonial cities of the ancien régime in North and South America (including an account of Pierre L’Enfant’s largely abortive plan for Washington) and British India. Girouard shows how these places related to European prototypes, but sharply describes them in their particular settings.

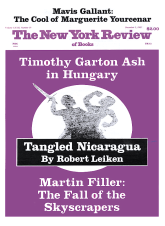

The last section begins with a masterly account of the “Exploding City” of the modern industrial world, from the nineteenth century—Manchester, London and its suburbs, and Paris—to the skyscraper cities of New York and Chicago. But the rest of this section is less clearly presented. “Cities Round the World” gets us to Meiji Tokyo, in which Girouard is diverted into some miscellaneous matters like water supply and sewage. The twentieth century is handled in a rather less confident way than the earlier material. “Babylon or Jerusalem” gives some account of modern “garden cities” and of contemporary US suburbs, but the author seems uncertain how much attention he wants to give to the cities we live in now.

Yet the book is a remarkable feat of literary planning, usually successful in linking the mood and visual appearance of what is now to be seen with the history of how it came to be so. Girouard compares cities diverse from one another in time and space, and does so with energy and verve, picking out common characteristics in a lively and undogmatic way. The emphasis is almost always on what is to be seen now, seldom on what is no longer to be seen, hardly ever on what was planned or dreamed but not executed. Failed utopias, the ideal building programs that were never built, are dear to many art historians but entirely absent from Girouard’s book.

The book’s main political drift is Whiggish in the British sense: the people who are seen as having power and prestige are mainly the landed and commercial oligarchies. The treatment of political power as it affects city life seems at first to be very bland; although in other books Girouard has shown himself to be well aware that power and architecture are inseparably tied together, he has very little to say about this here. The city has always provided a spectacle for the exercise of political power. Girouard is quite content tacitly to acknowledge this so long as he is dealing with Italian merchants, Dutch burghers, East Indian merchants, and great British landowners. But he is otherwise reluctant to acknowledge what has to be admitted by any historian, be he liberal or Whig, that the city has, beginning with its Roman prototype or earlier, been as often as not the showpiece for despotism (whether enlightened or not) and imperialism.

There are one or two striking examples which gloss over the exercise of imperial power. Two great town-planning demonstrations of British imperialism of the early twentieth century—the Mall in London and Lutyens’s arrangement of public buildings and routes in New Delhi—are both represented here as being in the American tradition of the “City Beautiful,” that is to say of long, landscaped garden vistas with very low density of population. The monumental aspects of these projects, with their huge arches and colonnades proclaiming imperial power, seem to have escaped Girouard.

Advertisement

Arguably, also, the Whig approach has influenced the organization of the book. It was, of course, absolutely necessary that Girouard should be selective: any attempt to deal with all the big Western cities would have reduced the book to a boring catalog. But it is noticeable that the main omissions among European cities are—with the exception of Paris and Rome, which could hardly have been omitted—the princely and imperial ones. Madrid, the classic example of an early modern city created by royal decree, is scarcely mentioned, and there is scant treatment of St. Petersburg, the other major imperial creation. The capital cities of the Austro-Hungarian empire are snubbed in the same way: Vienna gets little mention until the nineteenth century, with the development of the Ring, and later for an affectionate commendation of the Karl Marx Hof. Prague, which has a not negligible or ugly patrimony of ancient building, is also ignored.

This “Whig approach” may have encouraged Girouard to undervalue one important function of certain great cities, that of public administration. In analyzing the medieval city, which he does in an informed and sensitive way, he tends to let himself be carried away by the obvious current of merchant enterprise and civic independence, and to play down royal power. His treatment of Paris, which was for many centuries the capital of a more or less absolute monarchy, is in this respect interesting.

The main reason for the importance of Paris in the preindustrial era was the presence of the royal court in the city or nearby, though plenty of economic and geographic factors reinforced its preeminence. Girouard acknowledges this, but does not always pursue its consequences. When he comes to the early modern period he dwells on the social importance of the ennobled lawyers, who staffed the Parliament of Paris, in a way not really justified by the facts; it is untrue that they formed a “city aristocracy,” if we mean by that a specifically civic nobility like that of Genoa or Venice. Girouard wants to represent all urban cultures as culminating in the “polite society” of the eighteenth century, and to this end he rather neglects the monarchies on which the “polite” oligarchies rested. He minimizes the propagandist aims of most of the urban projects of the French kings (and, indeed, those of their Napoleonic successors) or explains them by a banal observation such as that they wished to “boost their image.” In the same way, Westminster and Whitehall are passed over rather quickly when Girouard touches on London. The relative independence of civic from national government in London, which was repeated in the North American cities, has perhaps affected the way Girouard—although he acknowledges the distinction—deals with cities where conditions were very different.

Like other historians of urbanism Girouard dwells at length on late Renaissance Rome; rather surprisingly he doesn’t try to dethrone Pope Sixtus V, the tyrannical Counter-Reformation zealot, from the pantheon of liberal and bien pensant town planners. The bishop of Rome was the only one of the medieval bishops of any account to remain the chief representative of public administration in the city; this had been the situation in many places after the end of the Roman Empire, but only in Rome did it continue. Rome was also the pattern for the later modern cities which depend on public administration for their very existence. These expensive havens for public service industries—financed, resented, and disliked by the rest of us—form an important category of modern cities that Girouard neglects to identify clearly. Washington, Canberra, New Delhi, Brasilia, post-1870 Rome, and now perhaps Brussels all come into this class.

Bloated and nasty as it is and was in many ways, Rome has influenced us all; Girouard’s appreciation of the Renaissance and baroque Rome is a sensitive one. His feeling for the social flavor of a town and a period is shown to advantage here: I especially liked his appreciation of the way in which Counter-Reformation Rome managed to combine theoretical intolerance of a very high order with practical arrangements that gave its cosmopolitan population an astounding freedom of opinion. He even compares Counter-Reformation Rome with Berlin in the 1930s: “a tolerant city landed with a regime which it disliked but had to live with.”

Advertisement

It would be surprising, given the worldwide range of his book, if Girouard had managed to get every street corner right. He makes a few slips about Rome. I do not think that Piazza del Popolo (which is far from the Via Paolina—or did he mean Via Paola?—which he places next to it) was very influential on other street plans before the late baroque: perhaps not even much before Valadier’s changes in the early nineteenth century. The ubiquitous influence which he assigns to it seems rather odd, and I wonder if he was not sometimes thinking of Piazza di Ponte, which is the terminus of Via Paola at the other end of the city.

Both apropos Rome and other cities, Girouard shows he is aware of the vanity of the idea that the great axially planned thoroughfares, which began in the Renaissance, and the ceremonial piazze and places that sometimes accompanied them, were means that automatically achieved the ends that government proposed for them, without the investment produced by private citizens for their development. The early modern governments did not have the resources to finance huge programs of urban renovation directly; they had to use their control of bylaws favoring urban development, and to resort to all sorts of other stratagems to attract urban investment. One of the great virtues of Girouard’s approach is his awareness of the laws of supply and demand, which are not always greatly regarded by modern town planners, though they are painfully present to practicing architects. He cites, for example, Louis XIV’s abortive “Place Louis-le-Grand” of 1685, which stood as empty façades put up by the royal masons with no buildings behind them, until the developers were much later persuaded to move in and to turn it into what became, eventually, the Place Vendôme.

One of the most enjoyable features of Girouard’s book is its treatment of the ways in which water can be brought into play in a city scene. Not surprisingly in someone who evidently has strong reservations about Ruskin, there is no fine writing about Venice; instead he makes the sharp remark that a medieval street system uniquely survives in the Venetian canals. But Girouard depicts the “water landscapes” of other ports, for example that of Amsterdam, with the ships “grazing” on its domesticated sea, in a way that does justice both to their natural features and to the works of man. He is also capable of Proustian appreciation of the landscapes where land and sea mysteriously fuse with each other. Preindustrial quays and cranes, with the isolated beaks of the latter brooding over the wharves (or, in Amsterdam, an island of cranes on the marine roads) are recalled vividly. His description of the approach to eighteenth-century Calcutta by the Hooghly River, as one glimpses the nine-mile parade of colonnaded houses through the hot greenery and the masts, is memorable (though could the Europeans lolling in their pleasure barges really be cooled with claret? I have never been cooled by claret, even by iced claret).

The Manhattan waterfronts may be described a shade grudgingly, and their squalid majesty a bit underplayed. Grand, monumental riverside fronts are not entirely to Girouard’s taste—hence, perhaps, the notable failure to do justice to St. Petersburg—but everywhere he shows himself aware of river views, and also of the transformations that river embankments work on a city. Only in Rome have the latter been entirely disastrous. Girouard also remarks on the number of public buildings that nineteenth-century governments tended to stack along the waterfronts, often mediocre buildings, although I suppose the eighteenth-century models like the Dublin Custom House can be defended. He can also produce remarks about water that are quite unexpected; for example, he observes that from an aerial view Manchester is as riddled with water as Bruges.

Girouard rightly emphasizes the way in which rich and poor often took their pleasures together in the ancien régime city. Many occasions were religious ceremonies or civic functions that were organized hierarchically, but some were licensed popular brawls. Both criminal disorder and communal violence have always been characteristic of city life, although Girouard is just as loath as the rest of us to admit it. His public entertainments are sometimes made to seem a bit more decorous than they really were; an example is the earlier palio of Siena, which was not just a classy horse race sponsored by the rich for the diversion of the poor. He shows illustrations of the stave fights on the Venetian bridges; another example was the Perugian giuoco dei sassi, in which opposing quarters stoned one another until an appreciable number on either side had been blinded. Down to the nineteenth century, one of the great civic pleasures (not stressed by Girouard) was the public execution, an event attended by all classes. Baudelaire, the great poet of urban ennui, dreamed of scaffolds as he smoked his hookah, and anyone who thinks that such things were unknown to the Victorians can read the description of a public guillotining in Arnold Bennett’s Old Wives’ Tale. The Carnival of the ancien régime was also, as Girouard says, a gross and coarse affair. It was another function attended by rich and poor which could end in riot and, occasionally, rebellion.

Girouard’s tendency is to stress the endemic violence of the medieval city, and to imply, quite wrongly I think, that this kind of thing has not been around so much since. For someone who apparently lived near Notting Hill during the riots there a few years ago I find this surprising. The book is silent on security measures to control the poor, though the poor quarters of the great cities in the last century and this have been governable only through careful policing, and it can be argued that without the development of police the city as we know it could not exist. How policing should be done is a political matter which neither Girouard nor I need go into, but the capacity to police must be there. Popular riots and insurrections were a problem not only in the late medieval cities (they were experienced not only by Italian and Flemish towns, but by London and Paris), but continued into modern times. Masaniello’s rebellion in seventeenth-century Naples, the Gordon riots in eighteenth-century London, seem to have made no impact on Girouard. There is a rather bored reference to Peterloo, the Manchester riot of 1819, and a brushing one to modern revolutions, but it would be hard to infer from his account that nineteenth-century urban authorities were terrified of popular disorder, and with good reason. Nor, indeed, has that terror by any means left them in many parts of the world, including plenty of “Western” cities. Napoleon thought that the ruler should use the executioner but never mention him in conversation, and perhaps there is a trace of this attitude in Girouard’s disdain to mention the police baton.

He is also a bit reticent on the popular diversions of the modern period. He mentions nineteenth-century race courses, but sports stadiums must be, except for railroad stations, the only large public buildings that hundreds of millions of people have voluntarily entered; the only one mentioned here is Lords, the London cricket ground. Of the worldwide diffusion of movie houses nothing is said, and it is a pity that he did not see fit to include material on British “public houses,” on which he has himself written a lively book.*

On the living quarters of the poor in the industrial cities of Europe and North America, Girouard has interesting things to say. He has been less curious about the lot of the very poor; beggars and the destitute get short shrift, although he is well aware of the architectural consequences of poor relief, in hospitals, orphanages, veterans’ homes, madhouses, workhouses, and so on. Much of this architecture reflects the theories of social improvement current at the time, particularly the Utopian, or Benthamite, or Saint-Simonian theories of the Enlightenment and early industrial periods. Perhaps because it prefigures the ideas of the do-gooders of the “Modern Movement” which he so cordially dislikes, Girouard has kept this architecture at arm’s length. He gives a good account of seventeenth-and eighteenth-century hospitals, but his best description of a hospital is of the late-medieval Ospedale Maggiore in Milan.

Girouard’s political emphasis may be slightly conservative, but he has supplied his readers with an enormous amount of information about the machinery of civilized urban life. His book is distinguished from many comparable ones by its optimism and its conviction that one of the main functions of the city is to provide us with civilized diversion. He thinks that cities are there to be enjoyed, and not to be suffered as a penalty for man’s revolt against nature. For him the urban pleasures originate historically in the “polite society” of the eighteenth century. What attracts him is the acquisition by a wider society of what had been court customs and pleasures: the transformation of the noble procession into the middle-class promenade; the appearance of the café, the public theater and opera house, the learned academy, and (he might have added) the Masonic lodge. All were social devices by which the Enlightenment sought to dilute noble privilege and to generalize courtly manners. He values positively the desire of substantial people to see and to be seen, as much on Grand and Drexel Boulevards in nineteenth-century Chicago as on the Row or in the Bois in Europe. He approves the nineteenth-century exhibitions for the same kind of reason. He assesses galleries, museums, great department stores not so much for their benefit to anonymous users but to that of civilized society. It comes through strongly that city people should in leisure hours have somewhere pleasant to walk and talk.

Girouard prefers pragmatic, pluralistic urban development to the utopian or rationalistic, and he obviously thinks that the demand for a unified organization of life which lies behind most modern town planning is deeply misguided. These convictions have made his treatment of twentieth-century cities more ambiguous than that of the earlier ones. In his concluding chapter, “Babylon or Jerusalem,” he explains some of the Utopian and Ruskin-based ideas of the idealistic movements in architecture and town planning, and their rejection of the industrial city. Perhaps because he has hesitated whether or not to confront the mid-twentieth-century city head-on, the exposition at this point is too selective. He seems to confer undue importance on those who wanted to run away from the industrial city, or to make city centers look like rural landscapes, like Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City Movement in Britain, or the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted in the United States. But he gives far less prominence to the architects and theorists who could be loosely described as the “Modern Movement,” and whose ideas were capable of being directly applied to the replanning and rebuilding of the great city centers.

Girouard makes his dislike of the Modern Movement plain enough, and he may be right in saying that the main work of modern town planning has been placed in charge of people who dislike great cities, and right too in implying that this planning has been in consequence bad. But the absence of a proper discussion either of Modern Movement theorists or of modern great city centers empties the claim of content; the closing sections of Girouard’s book are polemical, but in a rather lopsided way. Enough is said or hinted on the subject to give the reader the right to ask for a more coherent picture of mid-and late-twentieth-century cities than is here offered. Le Corbusier is dismissed in a couple of brief and snubbing paragraphs; Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe and Arne Jacobsen are not even mentioned. The last few paragraphs of the main text give an ironic, cheeky, and slightly confusing picture of present-day Los Angeles treated as the apotheosis of the Anglo-Indian bungalow. One realizes, on reading the epilogue, that Girouard has treated Los Angeles in this way because its low-density, unstructured plan seems to him (though still bad) better than the high-density, skyscraper-encumbered centers of other modern cities.

Only at its end does Girouard’s book lose its clarity. Throughout it has zest, energy, and warmth. All sorts of urban settings of which he theoretically disapproves can interest and stimulate him, from downtown Tokyo to working-class Vienna and Californian suburbia. Nicety has made me grouse at his neglect of this or that facet of urban history, but his book deserves appreciation for its scope, its visual sensitivity, and its range of civilized response. In his travels Girouard has been a restless soul, pushing beyond the obvious “sights.” In Calcutta he gets to the north of the city to the Bengali-built eighteenth-century palaces; in Manchester he has looked at Chorlton and Salford, in Chicago at Lake Forest and Riverside. When he looks, he sees people and buildings, not footnotes, and this distinguishes his book from those of a good many urban historians.

This Issue

December 5, 1985

-

*

Victorian Pubs (Yale University Press, 1984).

↩