Fears are mounting that the psychiatrist Anatoly Koryagin is near to death in the notorious jail of Chistopol in central Russia. Letters that have reached the West from his wife and a friend indicate that he is so weak that unless he is given expert medical care he could die at any time.

Dr. Koryagin has been in prison for the last four years for actively opposing the political abuse of psychiatry. The abuse takes the form of labeling dissidents as mad and forcibly treating them with drugs in mental hospitals.

Koryagin is an unfanatical man of forty-seven, married to another doctor and the father of three boys. His motives are human compassion and a strong concern for medical ethics. His sentence of seven years’ hard labor plus five years’ internal exile was longer than those imposed on other members of his human rights group, evidently because he was the only psychiatrist in it and the authorities were anxious to intimidate his fellow psychiatrists into silence.

Koryagin had examined sixteen dissidents who had been labeled mentally ill for their dissent, and found that the diagnoses were false. His main report on his work was published in the British medical journal The Lancet, and has just been printed in the book The Breaking of Bodies and Minds, edited by Eric Stover and Elena O. Nightingale (W.H. Freeman). In recognition of his work and his courage Koryagin has been elected an honorary member of the World Psychiatric Association and of leading psychiatric and scientific bodies in Britain, America, France, Canada, and elsewhere.

Ever since his arrest Koryagin has been subjected to a gradually escalating series of psychological and physical pressures, then to outright beatings. The unconcealed aim has been to force him to sign a false statement denouncing his own evidence of psychiatric abuse.* Since this aim has been thwarted by his consistent refusal to go against his conscience, the authorities have evidently begun to consider bringing about his death.

Their technique has been to isolate him from other prisoners; then, by putting mental and physical pressure on him, provoke him into his only means of self-defense, the hunger strike. Then, although Soviet regulations require them to keep him alive through force-feeding, they keep him hovering on the brink of death, too weak to start eating again without expert help, even when he wants to. The apparent hope is that his heart will eventually give out and he will die. In that event the authorities will have documentation to “prove” that they did everything they could to preserve his life. This interpretation of their behavior is confirmed by the new letters from Russia I have mentioned as well as by the fact that several other political prisoners have died in similar circumstances in the USSR in recent months.

No friend or relative has seen Koryagin since September 1983. For a year up to last June no communication of any sort was received from him. Then his wife got a letter containing advice on how to bring up the children, but with no information on his own condition. He may, it is feared, have written it in anticipation of his death.

The letter from his wife, Galina, who lives in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov, was written last November but only recently received in the West. She refers to a six-month hunger strike begun in December 1982, and comments that “it was only by some miracle that he survived: his life hung by a thread.” Then a family visit was allowed in September 1983:

When I saw Anatoly, there was nothing in my heart but horror—fear for his life, compassion, and anguish at my powerlessness to help him.

The visit lasted two hours; for about an hour I couldn’t speak, because of the convulsions in my throat. The talking was done by him, his mother and the children. I immediately understood, without words or explanation, what had happened. He was like a medusa, so bloated that his neck was wider than his face. It was covered with oedemas caused by protein starvation.

Throughout his imprisonment he’s been constantly reduced to a state of extreme weakness…by the torture of cold, hunger and sleep deprivation, of harassment, humiliation, mental agony, and even beatings. So it’s hard, even terrifying for me to imagine how he is now (after a new hunger-strike).

The letter from Koryagin’s friend, which was written in June and reached the West last week, is an appeal to doctors throughout the world. The author is well known to Koryagin’s friends in the West, but, in the current repressive climate in the USSR, prefers to remain anonymous. Extracts from the appeal follow:

I remember Tolya Koryagin as a tall, handsome, broad-shouldered man, with a good-natured smile. That’s how he was when first he entered our house, and that’s how he looked when I saw him last, not long before his arrest. It’s terrifying what they’ve turned him into during his years in prison—a virtual corpse, bloated from almost continuous hunger-strikes, sprawled on a crude prison cot…. They beat him brutally.

There are no words to describe the pain and humiliation of artificial feeding. Andrei Sakharov (the famous physicist), according to his family’s reports, gave up his hunger-strike last year after a month: “It was too torturous,” he explained.

Anatoly Koryagin has been on hunger-strike for nearly a year. He is slowly dying in the Chistopol prison. His family is suffering dreadfully in Kharkov.

I appeal to all the doctors of the world, and also to each of you individually. Today your colleague, the doctor Koryagin, is near to death because of his loyalty to the Hippocratic Oath. Today he and his family need your immediate help. Tomorrow it may be too late. I ask you to do everything to secure the immediate emigration of Anatoly Koryagin and his family from the USSR.

I suggest that as this can’t be done by normal means, you make the Koryagin family’s immediate emigration an absolute condition of any cooperation with the health organizations of the USSR.

You have the real chance to save a human being’s life.

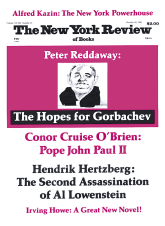

—Peter Reddaway

This Issue

October 10, 1985

-

*

For Koryagin’s own description of his prison experiences up to 1982, see The New York Review (March 3, 1983).

↩