In response to:

Crimes Against the Cubists from the June 16, 1983 issue

To the Editors:

In connection with the article, “The Crime Against the Cubists [NYR, June 16], I would like to make the following remarks:

The article is very sensitive and important, and much of it, especially the parts concerning wax lining (not “relining” which means repeating the operation at some later date), are true for all canvas paintings, not just the Cubists.

However, here the author goes into a field in which he is no expert. I am referring to his footnote 1 on page 32, where he “evaluates” various adhesives in a way which might be damaging and misleading.

When he says “Some of the alternatives to wax relining are still in the experimental stage,” he implies that wax-resin adhesives were thoroughly tested and found acceptable. This is not the case: Wax resins were introduced without any serious testing, and over the objection of numerous experts who immediately complained about their staining. All later tests brought up more and more damaging qualities.

The statement “as of now…cold lining is the only gentle and reversible method” is inaccurate. There is a process which successfully uses heat and pressure. However, heat and pressure must be applied by persons who have familiarized themselves with the technique. The author mistakenly includes the Beva process among those where “excessive heat and pressure” are applied.

Beva was the first adhesive to be formulated specifically for art conservation. Unlike other adhesives which were formulated for general purposes and are used incidentally for art conservation, Beva was the first ever to undergo stringent standardized tests along the lines of ASTM (American Society for Testing Materials).

Beva is gentle and reversible, and can be effectively used at room temperature (21°C, 72°F). It can be used on the suction table without any pressure at all. Lining with Beva, using no pressure, was demonstrated before several professional gatherings, notably the International Symposium on Comparative Lining Techniques in Greenwich, London (April 1974), where a dried Monarch butterfly was part of the collage being lined.

Unlike other adhesives, the exact formula of Beva (all its contents) as well as the testing system were published in the professional literature.

Incidentally, we thoroughly agree with Mr. Richardson with his description of what was done with the Cubist paintings as a crime.

Gustav A. Berger

Conservator, FAIC, FIIC

Contributing Member, ICOM

Committee for Conservation

New York City

John Richardson replies:

My thanks to Mr. Berger for denouncing the excessive restoration of Cubist paintings as “a crime,” the more so since this conservator is well known for his contributions to the technology of relining. Sad, however, that Berger’s objectivity evaporates the moment Beva is mentioned. Why? He does not say so, but the Beva process is his invention—one that he markets to others in the field. His letter should be seen in this light.

Berger questions my technical expertise. True, my competence is in the field of art history as opposed to conservation. But I do not see that this invalidates anything I said. Moreover, as I explained in the October 13 issue of The New York Review, I had the technicalities in my article (and in this letter) checked by an eminent expert.

I would be more reassured by Mr. Berger’s statement that the Beva process does not involve “excessive heat and pressure” if research had not unearthed a contradiction between his claim (seventh paragraph) that Beva can be used at room temperature (21 degrees Celsius) and his often repeated recommendation that the process should be activated at from 60 to 65 degrees Celsius. As Berger conveniently fails to explain, it is not only high temperatures that are dangerous. The Beva-ization of ultrasensitive Cubist paintings at a low temperature could also be a risky business. In a paper read to the National Maritime Museum conference in April, 1974, Berger admits that unless this process is very carefully watched, there is a “…danger of bond failure as well as of staining….” Also we have no way of predicting the long-term consequences of synthetic adhesives.

As for Berger’s ingenious lining of a collage that included a Monarch butterfly, the wisdom of applying the same process to Cubist canvases is questionable, since it could cause the Beva adhesive to seep into the back of the original support; and this is just the sort of thing that dismays those of us who want to carry out the artists’ wishes and at all costs protect the delicate constitution of Cubist paintings.

In my article I confined technicalities to a footnote in the hope that my thesis—that varnish and wax lining have done irrevocable damage to Cubist paintings—would not become a pretext for nit-picking. The attempt to keep technicalities in perspective has demonstrably failed. Berger’s letter is more sagacious than Mrs. Keck’s, but by blowing their own trumpets both correspondents cause one’s heart to sink. If only they would show as much concern for the well-being of works of art as they do for the credibility of their pet processes. Not that conservators are necessarily more to blame than art historians. In the circumstances both sides—indeed everyone in the field—should join forces to see what can be done to save Cubist paintings and other endangered species of art.

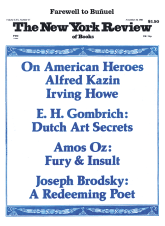

This Issue

November 10, 1983