The journals and papers which make up The Forties are of great interest—coming from Edmund Wilson, it would be very odd if they were not—but taken as a whole the book is not really in the same class as The Twenties and The Thirties. For one thing, as Leon Edel makes clear in his excellent introduction, it lacks the advantage of Wilson’s own preliminary editing, and of the retrospective passages that he would have added if he had lived. For another, the material that Mr. Edel has had to work on—the more intimate and informal material, at least—is relatively skimpy. During the first half of the 1940s, while he was still married to Mary McCarthy, Wilson scarcely kept a personal diary at all. He slipped back into the habit from 1946 onward, but on a much less substantial scale than before; and as a result, the greater part of The Forties is taken up with first drafts of material that has already appeared elsewhere, often in very similar form—principally in Europe Without Baedeker and in his accounts of the Zuñi Indians and his visit to Haiti, the “red” and “black” sections of Red, Black, Blond and Olive.

The book does naturally provide some sense of the course that Wilson’s life took during the decade, in particular of the happiness which his fourth and final marriage brought him. But there are some very obvious gaps and omissions as well. To stick to literary matters, for instance, there is next to nothing about his reviewing for The New Yorker, little of note about Memoirs of Hecate Country, not a single mention of The Shock of Recognition—although that very active anthology, so much more than a mere compilation, was not only the most solid piece of critical work that Wilson published in the mid-1940s, but must surely have played a major part in the shift of interests which led eventually to Patriotic Gore. And if The Forties is only to a very limited degree a chronicle of Edmund Wilson’s 1940s, still less can it pretend to be a chronicle of the 1940s. For much of its length—in marked contrast, here, with The Thirties—politics and public affairs scarcely impinge.

As far as the new material goes, then, the book is a collection of fragments. A few of them are rather boring—I must admit that by the end I found all the neat, conscientious descriptions of pond life and wildlife beginning to pall—and some of them no longer have much point, but for the most part they bear the unmistakable stamp of Wilson’s vigorous and invigorating personality. Again and again, whether he is describing a journey out west or the death of an old friend, or mulling over subjects as far apart as aviation (its constricting effect on our view of the world) and early nineteenth-century prose (its peculiarly “viscous” quality), he succeeds brilliantly in hitting the nail on the head and pinning down the elusive shade of feeling. Even the casual observations of such a man are worth preserving. So are the idiosyncrasies. He can be generous, admirably open to experience, severe where severity is called for. He can also be perverse and, on occasion, absurdly crusty. Thus, to take a minor example, we are treated to the spectacle of Edmund Wilson (aged fifty-three) deciding, on the strength of Kiss Me, Kate, that Cole Porter (aged fifty-five) is showing clear signs of senility. Truly wunderbar—and the kind of detail one would be sorry to forgo.

I am not sure I would claim as much for the sexual couplings recorded in the book. They are well described, about as successfully as such things can be—but how successfully is that? On the other hand the bedroom scenes do seem to me more effective than similar episodes in the two earlier volumes. They are less ostentatious; there is less of an awkward feeling that we are being invited to applaud what Wilson refers to in The Thirties as his “large pink prong.”

As for the first drafts and the working notes, it is often instructive, in a mild way, to compare them with the finished product. Missing names are supplied, details are filled in, we can see what Wilson chose to omit and ask ourselves why. Take the interview in Rome with George Santayana, for instance, from Europe Without Baedeker—an outstanding Wilsonian portrait. It now turns out that the “very great man” who Santayana mockingly said was coming to visit him was in fact Jacques Maritain; that the philosopher had just been reading, with evident admiration, the Victorian novelist Charlotte M. Yonge (a very English, very Church-of-England writer—it set me thinking about the rather rose-tinted parsonage scenes in The Last Puritan); that Wilson originally wrote that there was “a shade of the feminine and the feline” about Santayana and then changed it to “a suggestion of something feline” before publication. Et cetera. It is all quite interesting, but none of it makes much difference—any more than it does, say, to learn about the minor details of Wilson’s routine while he was living on the Zuñi reservation. Such things will no doubt have their value for his future biographer, but in comparison with the final work of art itself, his splendid account of the Zuñi ritual dances, they are so much wrapping paper and straw.

Advertisement

There is at least one section of The Forties, however, where some more background information would have been welcome—the account of Wilson’s visits to London in 1945. When Europe Without Baedeker first appeared the English episodes caused a good deal of resentment all round. The book was badly received in England, where readers were irritated by what they saw as its anti-English bias; at the same time American readers were presented with a picture of a distinguished American author being snubbed and patronized by his hosts and subjected to some fine old-fashioned English discourtesy. It is all ancient history now, but the affair still has its puzzling aspects.

Wilson himself naturally denied that there was any question of prejudice. It was, instead, the old story: one more example of the English, always so willing to hand out criticism to others, being unable to take it themselves, especially when it came from Americans. He had simply set down his reactions to what he had seen and heard, and in the course of doing so he had found himself telling a few home truths. He could also claim, with some justice, that the book contains a fair number of compliments to the English as well. There is an account of a visit to the House of Commons which is almost touristy in its enthusiasm; his encomium of Peter Grimes (recently reprinted in the Cambridge University Press handbook to the opera) still stands up well; he records some perfectly pleasant encounters and conversations.

Yet I think that he was deluding himself if he honestly supposed that he does not often reveal an antagonism over and above the call of duty. It is not so much that he tends to concentrate on all that was seediest and sleaziest in London at the time—although he does—as that he gives the impression of positively looking for trouble, and bristling whenever an Englishman crosses his path. And not only in England itself, either. His most barbed descriptions are reserved for some of the British officers and officials whom he came across in Italy and Greece, culminating in his unforgettable portrait of the retired proconsul whom he calls “Sir Osmond Gower,” a prodigy of elderly self-conceit. (Sir Osmond was in reality Sir Ronald Storrs, and while I am sure that everything that Wilson says about him is true, he was a much more interesting man in his prime than can be readily gathered either from Wilson’s sketch or Mr. Edel’s footnote. His autobiography, Orientations, is, or ought to be, a minor classic of sorts: the account of his time as governor of Jerusalem, whatever one may think of his politics, is particularly engrossing.)

One thing that Wilson’s notes in The Forties confirm is that if he did let fly at the British, it was not without a certain amount of provocation. There is Maurice Bowra, for instance, announcing that he has never read Whitman, and, on being informed by Wilson that Leaves of Grass is probably the greatest single work by an American author, exclaiming, “Better than Whyte-Melville?” Or Evelyn Waugh, keeping up a tiresome pretense when they first meet that Wilson is either a Rhodes Scholar preoccupied with Henry James or a simple soul from Boise, Idaho. Or Henry Green, who puts in a brief and bigoted appearance which is unlikely to win him many new admirers.

The Bowra incident is something of a case apart. One can never be sure, but from all I know of Bowra it seems to me highly improbable that he had really not read Whitman—omniscience was his foible—and far more likely that he was teasing, and that when Wilson took him seriously he could not resist cutting short the conversation with a joke. (Shouldn’t Mr. Edel have provided a note, incidentally, explaining who Whyte-Melville was?) It was not a particularly good joke, perhaps—but still, it was only a joke, and it is a pity that it should have come between two men who had many qualities in common. Late in life, I am glad to see from his letters, Wilson finally came around to Bowra after reading his memoirs.

Advertisement

What still remains unclear is how Wilson dealt with the “British rudeness” of which he so frequently complains. There is a memorable sentence in a letter from Mrs. Henry Adams to her husband, describing an evening in London where she was escorted into dinner by a baronet who immediately started making disparaging remarks about Americans: “He was insolent, and I was obliged to tomahawk him on the stairs.” It is hard to believe that Wilson, a man not exactly lacking in combative instincts, did not sometimes reach for the tomahawk too, but in general he tends to present himself as the passive recipient of other people’s gibes. If he did hit back, most of his rejoinders have gone unrecorded.

Another puzzle is, whom did he actually see when he was in England? That he should have been anxious to meet Waugh is not to be wondered at: he had already published an essay in which he spoke of him as “the only first-rate comic genius to have appeared in English since Bernard Shaw.” (Waugh was to reciprocate by describing Wilson in his diary as “an insignificant Yank.”) But who were the other writers he met, apart from the handful he mentions in passing? Surely the conversations he had with some of them must have been more congenial, more impressive even, than those he describes? Here again The Forties leaves us almost as much in the dark as we were before.

If one feels rather frustrated it is largely because any reader of Wilson’s essays can see how strongly he responded to English writers (and since he was Wilson that meant to their lives as well as their work)—more strongly, in many cases, than he seems to have done to American writers of roughly the same rank. Nor is there any sign that his interest ever slackened: indeed, his last, posthumously published collection takes its title from an essay on one of his old English favorites, Barham’s Ingoldsby Legends. And as for contemporaries, you will find very little in his later books about American writers who have emerged since the 1940s, but you will find essays on Angus Wilson and Kingsley Amis.

His intimacy with English literature went back to childhood, and it can hardly have failed to have been bound up to some extent with feelings about his background and the social caste into which he was born. (One of the more cryptic entries in the notebooks reads, “My relation to the English and my relation to my father: accent, handwriting.”) It had also, he felt, left him unprepared for what life in England was really like. “The point is,” he wrote in his preface to the second edition of Europe Without Baedeker, “that when we read English writers in youth, we assimilate them so far as we can to ourselves and treat the rest as a kind of fairy tale.” Not that the fairy tale was necessarily untrue: on the contrary, one of the lessons that had to be learned was that what an American reader took for fantasy—the caricature in Dickens, the cynicism in Thackeray—often turned out to be solid social realism.

There was a deeper animus at work than this suggests, however, one which pretty obviously had its chief source in politics. “I have become so anti-British over here,” he noted at one stage in his journal—he was in Italy at the time—“that I have begun to feel sympathetic with Stalin because he is making things difficult for the English.” Sentiments like these were by no means rare at that period—they may even have found an occasional echo in high places—but in Wilson’s case they were at least largely based on an honorable if somewhat simplistic anti-imperialism. Largely, but not entirely. There was something in him of a frustrated Marxist, and something of a frustrated isolationist, and from either point of view he was tempted to play down the significance of the British role in World War II, perhaps even the significance of the war itself. It is an impulse that found its clearest expression in his repeated attempts to represent Churchill in as unflattering a light as possible, preferably as a pistol-waving desperado. His account of the Siege of Sidney Street, for instance—a notorious gun battle in the East End involving a group of anarchists at which Churchill, who was then home secretary, was present—manages to be so inaccurate that I am half-inclined to suspect that he got his version of the facts from Harold Laski, whom he had heard referring to the episode in an election speech. And just about the least happy inspiration anywhere in his work must surely be his whimsical interpretation of Arsenic and Old Lace as an allegory of the war, with Churchill as the lunatic who keeps charging upstairs under the impression that he is Teddy Roosevelt at San Juan Hill.

In the end I doubt whether The Forties will affect Wilson’s reputation one way or the other. It does contain one potentially fascinating new item, some notes for an autobiographical novel made around 1941 or 1942. This would have been a very different kind of book from Hecate County: it was conceived of as what Mr. Edel calls “a fantasy of ‘ego-integration’,” in which three separate selves—personified by a jazz-age romantic, a Soviet bureaucrat, and a determined individualist who has settled in Provincetown—are finally allowed to merge. An interesting notion, but the notes as they stand are too embryonic for one to be able to judge whether Wilson was wise to abandon his plans for the book or not.

The fiction which he did publish was obviously not in the same class as the best of his criticism. But that does not mean that it is negligible, any more than his poetry is. In the recent collection of Archibald MacLeish’s letters there is a scrap of verse that MacLeish sent to Hemingway, written while he was still recovering from the painful experience of reading “The Omelet of A. MacLeish” for the first time:

I took the whole frustration on the nose.

The wish to be a poet: the ambition

To think of Daisy in immortal prose:

The hope to publish in a limited edition….

No doubt at some deep level, given the aspirations he set out with, Wilson did have to learn to live with a sense of creative unfulfillment. But I Thought of Daisy still seems to me an excellent novel—immortal or not, it has stood the test of time so far—and his poetry has many more virtues than its current reputation would suggest. (The only critic I know of who has done it justice is Clive James, in the symposium on Wilson edited by John Wain a few years ago.) The truth is that he was a rather more interesting poet than MacLeish.

Apart from the imperishable “Omelet” Lewis M. Dabney has not included any of the poems in The Portable Edmund Wilson, which is a pity. But with such an enormous range of work to draw on sacrifices are inevitable, and quibbling is all too easy: it is clear that Mr. Dabney has thought out his editorial policies very carefully, and in general it is hard to see how the job could have been better done. All Wilson’s major interests are well represented; the reporter is as much in evidence as the historian; the material has been skillfully arranged to provide a clear view of Wilson’s development over the years, and Mr. Dabney himself contributes a long, close-packed introduction and some helpful notes. Within the limits of portability it is everything that could reasonably be asked for, and even readers who know Wilson’s work well will find that they come away from it with a renewed sense of his manysidedness and his prodigious gifts.

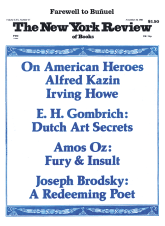

This Issue

November 10, 1983