In response to:

Discrimination and Thomas Sowell from the March 3, 1983 issue

To the Editors:

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, straw men must be a close second. No critic would have to invent a position to attack if he could deal with the real arguments.

Christopher Jencks’s voluminous review of Ethnic America and Markets and Minorities [NYR, March 3, March 17] repeatedly creates straw men, with which he is repeatedly “astonished.”

Straw Man: According to Jencks, my position is that “discrimination tends to disappear once markets become competitive.” Markets and Minorities: “The competitiveness of the market puts a price on discrimination, thereby reducing but not necessarily eliminating it” (pp. 39-40).

Straw Man: “Discrimination…tends to disappear once government stops enforcing it.” Ethnic America: “Translating subjective prejudice into overt economic discrimination is costly for profit-seeking competitive firms, although less so for government, public utilities, regulated industries like banking, or nonprofit organizations such as universities or hospitals” (p. 292).

Straw Man: “…current discrimination in the labor market has no effect on black earnings.” Ethnic America: “The point here is not to definitively solve the question as to how much of the intergroup differences in income, social acceptance, etc., have been due to the behavior and attitudes of particular ethnic groups and how much to the behavior of the larger society. The point is that this is a complex question, not a simple axiom” (p. 294).

Straw Man: “…if the median black, Indian, or Hispanic were as old as the median European, he would be almost as affluent.” Markets and Minorities: “Differences in median age are only part of the statistical picture” (p. 11).

Straw Man: “Sowell argues for patience.” Since I don’t even discuss any such thing in either book, there is nothing to quote. But in the first book I wrote on the subject, I said at the outset: “History…gives little support to the view that time automatically erodes racial aversions, fears, and animosities, or even tames the overt behavior on such feelings” (Race and Economics, p. vi). All my subsequent books on ethnicity make it a point to show retrogressions in intergroup relations over time, as well as examples of progress. Markets and Minorities mentions these retrogressions (pp. 72-73) and Ethnic America discusses them repeatedly (pp. 71, 82, 161-162, 192, 201-202, 203, 204, 206, 210-211, 254). I shall leave it to Jencks to supply the pages where I argue for “patience.”

Straw men are not incidental but fundamental to Jencks’s critique. Neither Ethnic America nor Markets and Minorities is a book about “special treatment for blacks,” however much that theme is proclaimed in Jencks’s headlines or repeated in his text. Anyone who seriously expects to find in these two books anything more than the most fleeting mention of that subject is going to end up feeling like he is looking for a needle in a haystack.

“What is in question here is Title VII of the Civil Rights Act,” Jencks declares at the beginning of his second review article. Although about half the article is about Title VII, and my supposed opposition to it, there are no quotes of anything I ever said about Title VII. There could not be any quotes from these two books on that subject, because there are none there. Jencks and his straw man do this whole act alone, with only passing references to what “Sowell seems to believe,” what “Sowell assumes” or “as Sowell would have it.” It is very much like “Duffy’s Tavern” or “Rebecca,” where the persons in the title role are repeatedly mentioned but never actually appear.

This is all the more remarkable because I have not been the least bit reticent about discussing Title VII—often and at length—elsewhere. Jencks need hardly have strained his imagination to try to extract my views on Title VII from these books—which are on different subjects, as anyone can tell simply by reading them, however much Jencks may choose to say that they are “in effect” books on affirmative action. Phrases like “in effect” are a blank check for straw men.

Where I have discussed Title VII,1 the first order of business has been to distinguish its provisions, and the legislative history behind them, from the policies subsequently evolved as “affirmative action.” It is the latter that I have criticized, not Title VII.

Jencks’s statistics on what has happened since 1964 might be relevant to Title VII, but not to “goals and timetables” (quotas) that became mandatory in 1971 affirmative action guidelines. Where I have discussed this issue, I have compared the progress of minorities under Title VII’s “equal opportunity phase,” as contrasted with the affirmative phase that followed. Jencks lumps it all together and credits post-1964 improvements precisely to the “affirmative action” phase, when they generally slowed down.

It is also worth noting that the historical trends at work go back even before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The number of blacks in professional, technical, and similar high-level positions doubled in the decade preceding passage of the Civil Rights Act. The sharp improvement in the relative position of Asians likewise preceded both “equal opportunity” and “affirmative action” policies.

Advertisement

Asians, incidentally, disappear mysteriously from Jencks’s arguments at the oddest moments. After unveiling “the crucial distinction between universal and haphazard discrimination,” Jencks applies this great dichotomy only to blacks and whites. Surely no one would claim that the massive discrimination against the Chinese and Japanese that pervaded generations of American history was only “haphazard.” Black West Indians are also not just black haphazardly (on the weekends, as it were), even though their incomes are just 6 percent below the national average—and 15 percent above the national average in the second generation.

My discussions of the effect of intergroup differences in age and geographic distribution are twisted to fit into Jencks’s framework, where I am supposed to be denying that discrimination has any effect on minority incomes. Specifically, they are transformed by Jencks into attempts by me to deny black-white differences. But Ethnic America and Markets and Minorities are no more books exclusively about blacks than they are books about “special treatment.” Both books give examples of how taking age or geographic distribution into account changes the statistical picture—as regards Hispanics and Asians, for example, as well as blacks. Indeed, Ethnic America points out that Japanese American income is exaggerated when regional and rural-urban differences are not considered (p. 177). Yet Jencks attempts to make the very same argument a telling counterattack to my alleged denials of discrimination. It may take two to tango, but Jencks has brought his own straw man.

Dismissing as “nonsense” the idea that age affects income, Jencks argues that age differences among heads of family “vary little from one group to another” and “have almost no impact on family income.” Census data published in the same Urban Institute book cited by Jencks show Puerto Rican family heads to be a decade younger than Japanese American family heads—and fourteen years younger than Jewish family heads.2 These are hardly trivial differences in work experience.

Some ethnic groups, of course, differ little in age or income, and it is by no means clear that their small differences in income have much to do with their small differences in age. Jencks seizes on precisely such groups to try to prove his point. Taking Czechs and Germans, or British and French, in America as his examples, Jencks shows that their relative income rankings in Europe are different from their income rankings in the United States. But here we are talking about groups whose incomes differ by a few percentage points—the kind of differences small enough to change from one census to the next. The real issue is about groups that differ by large amounts in income. Here an international comparison would be devastating to Jencks’s thesis.

Germans and Jews are not only more prosperous than Hispanics in the United States; they are more prosperous than Hispanics in Hispanic countries. The Chinese not only have higher incomes than blacks in the United States but also in black countries such as Jamaica. The Japanese not only have higher incomes than Mexicans in the United States, but also when comparing Japan and Mexico—even though Mexico is rich in natural resources and Japan is almost destitute of natural resources. The Chinese not only make higher incomes than the Malays in Singapore, which is Chinese, but still more so in Malaysia.

Not only do large economic differences between groups repeat themselves in country after country; the very occupations and fields of study of these groups also repeat. Pianos were first made in the United States by Germans and most of the leading piano firms in the United States today still reflect that German influence in such names as Steinway, Knabe, and Schnabel. The first pianos in Australia were also produced by Germans. So were the first pianos in England. The Chinese are as vastly overrepresented among students of mathematics, science, and engineering in Malaysia as they are in the United States. Jewish peddlers followed in the wake of the Roman legions and in the wake of the wagon trains on the American frontier—and in many places and times in between.

Even the most textbookish exercise in Markets and Minorities is twisted to fit Jencks’s dogma that I deny that discrimination has any effect whatever on minority incomes. In order to illustrate the point that the same set of data can often point to opposite conclusions, according to the level of aggregation or the analysis used, Markets and Minorities reproduces data on blacks and Hispanics from a study by Eric Hanushek and shows the opposite interpretations that can be drawn. Then the same thing is done with some census data on the Chinese. The conclusion of this lengthy exercise is explicitly methodological:

Advertisement

The main point here is that gross income deficits between a particular group and the “national average” do not not prove or measure discrimination—nor do gross income advantages disprove it (p. 26).

Enter Jencks, lower left. Because I have said, in the course of this exercise, that a particular table does not prove discrimination, Jencks turns it completely around and claims that I have said that that one table disproves discrimination against blacks and Hispanics. He finds this conclusion “astonishing.” I am a little staggered myself, especially when he follows that up by claiming that I have falsely cited Eric Hanushek in support of this novel doctrine that he attributes to me. Lest anyone think that Professor Hanushek is an unindicted co-conspirator, let me point out that he plays exactly the same role in this example as the Census Bureau: He is listed after “Source” (and “adapted from”) under a table of numbers. He is neither mentioned, quoted, nor cited in the text where I drew my conclusions. I haven’t the faintest idea what his opinions are on this subject.

After his empirical forays, Jencks turns philosophical. He criticizes those economists who prefer individuals to make their own decisions rather than have government impose decisions on them. This, according to Jencks, invests individuals with “implausible virtues” and proceeds as if “private citizens always act in their own best interests.”

Words like “always” are among the most valuable words in the language. They let you know when an argument isn’t even serious. Practically nothing “always” happens among human beings. The logic of this argument is that we should send in a pinch hitter because the regular batter doesn’t “always” get a hit. And what sort of miracle man is this pinch hitter?

Jencks points out that people “often lack the knowledge or the wisdom” to make the right decision, and so must turn to experts. Nothing wrong with that. It happens all the time. We have all heard of doctors, pollsters, marriage counselors, and weather forecasters, not to mention parents, Dear Abby, and Barbara Woodhouse. What is truly astonishing (if Jencks hasn’t copyrighted that word) is the casual ease with which he glides from this widespread voluntary use of other people’s knowledge to being forced to do what we are told.

Even in matters of life and death, we apparently don’t have a right to decide where we think our chances of survival are better. Jencks objects to a passage in Markets and Minorities that criticized the British parliament for regulations imposed on ships taking emigrants from Ireland during the famine of the 1840s. The new laws may have improved sanitation on these ships, thereby saving some lives, but they also raised the fare and some people who couldn’t pay it may have remained behind to starve to death in Ireland.

Markets and Minorities points out that the Irish immigrants rushed to get on these ships (at the lower fares) before the legislation went into effect, suggesting that they preferred not having these “improvements” at the costs they entailed. Jencks objects that “Sowell’s criticism of the legislation does not rest on evidence regarding its net effect on mortality.” I have no such evidence—and I suspect that Jencks doesn’t either. Nor is it clear why people fleeing a famine should have to wait until two academics sift through the statistics a century later.

Statistics are always collected after the fact, while decisions have to be made beforehand. The seductive fascination of a vision of “rational planning” by the government might be far less if this plain fact could be remembered. Neither the individual nor the government will “always” be right. The real issue is, who has a right to choose among the inevitable risks—those who stand to gain or lose, or those who can talk most plausibly from the sidelines?

Eager as some may be to exercise their moral and intellectual superiority for the greater good of the masses—often a fatal exercise for the latter—the issue of freedom cannot be made to disappear by verbal sleight of hand about expertise. Nor is this moral superiority all that apparent. Jencks asserts that politicians “are different from used-car salesmen.” I say it is too close to call.

The anointed may be chomping at the bit to run our lives for us, but the jury is still out on whether we are to be directed from above by those who have the insight, the objectivity, and the accuracy which Christopher Jencks has displayed.

Thomas Sowell

Hoover Institution

Stanford, California

To the Editors:

Christopher Jencks is rather gentle with Thomas Sowell’s ideological tracts on race and ethnicity. He is also rather naive about the job market in the United States. He writes that “in light of the extraordinary progress of both black women and highly educated black men over the past decade, I think we must assume that firms are telling the truth when they say they have trouble finding black male high-school graduates who perform well in the skilled, responsible, fairly well-paid jobs traditionally reserved for white male high-school graduates.”

That might be technically true in the narrowest sense. But Jencks must be aware of the fact that one of the strongest bastions of race discrimination has been the skilled trade unions. Most of them fought bitterly to keep blacks out of their apprentice programs; and most of them still keep the number of blacks allowed into those programs to the barest minimum. Why else would blacks be in the laborers’ unions in the building trades, but in only token numbers in the electricians’, bricklayers’, or carpenters’ unions? If “firms” have trouble finding skilled black workers, it is not because they don’t know where to look.

His references to “high-risk” young blacks who have trouble finding work has that same naive quality. In many major industrial cities factories which might employ such unskilled people have been closed and been replaced (in smaller numbers) by newer plants in the distant suburbs. Housing discrimination keeps black workers out of those suburbs and poverty and the decline of public transportation deprives them of access to routine production jobs. It is interesting that in the 1960s, before the decline of the Chrysler Corporation, black workers made up a majority of the work force in Detroit and the near suburbs. It can be assumed that black workers are employable, but also that discrimination is more pervasive than simply in employment. Housing discrimination and suburban hostility to cities with black majorities also play their parts.

Martin Glaberman

Wayne State University

Detroit, Michigan

To the Editors:

Christopher Jencks’s honest and humane essay on affirmative action faces up to the fact that the only effective way to enforce anti-discrimination laws is to hold each employer to some numerical standard which amounts to a racial quota. At the same time, Jencks acknowledges that reverse discrimination outrages a lot of people, reinforces stereotypes about black incompetence, and does little to encourage achievement among black people who are led to expect that jobs and promotions will be doled out by race rather than by accomplishment.

Accordingly, Jencks suggests that reverse discrimination is now doing more harm than good and should be abandoned, and more modest quotas should be enforced simply to ensure that employment decisions are colourblind—i.e., to ensure that competent blacks are not being victimised by various kinds of invidious discrimination. I don’t see how it will work.

No “hiring goal” can be based on the black proportion of “best qualified” applicants, because you can’t assess who is “best qualified” except by comparing the actual applicants for each job. For instance, in the example Jencks gives of academic hiring, you can’t define a quota for a university on the basis of what proportion of the “best” publications in a given field is written by blacks (and so ensure that the “best qualified” people are hired regardless of race) because you don’t know in advance who will actually apply to that university or how many blacks will be the “best qualified” people who do.

So hiring quotas have to be based on a judgement of what proportion of all potential applicants are blacks who are “generally qualified” or have the minimum necessary qualifications. As Jencks suggests, this is not so easy to do, because for a lot of jobs there is sharp controversy about what qualifications are “valid”—i.e., what qualifications actually predict good performance on the job. In fact, this controversy inevitably arises about any qualification that blacks or other minorities are disproportionately unsuccessful in getting. Despite the difficulty in deciding what qualifications make one competent, and despite the impossibility of taking potential applicants’ personal qualities into account, what the courts and government agencies actually do is set “ultimate goals” on the basis of how many blacks, proportionately, seem to be “generally” or minimally qualified for the job.

The trouble is that this opens the door to “reverse discrimination,” because to satisfy the quota an employer may have to hire “qualified” people (however this has been defined) who are less qualified than available white applicants. It would be marvelous if you could know in advance how many of the “best” applicants to each employer will be black, and set a quota accordingly, but the point of all this is that you can’t. The choice seems to be either to abandon quotas and make it very difficult, practically, to stop various kinds of discrimination, or to carry on with a certain amount of reverse discrimination despite its moral ambiguity and its demoralising effects.

Is there another way?

Maimon Schwarzschild

University of San Diego School of Law

San Diego, California

Christopher Jencks replies:

Let me begin with an apology. I should not have said that Professor Sowell “argues for patience.” He doesn’t. What I meant, and should have said, was that by emphasizing parallels between blacks and other ethnic minorities in America, and especially by emphasizing the fact that the transition from rural poverty to urban affluence has almost invariably taken several generations, Ethnic America strongly suggests that blacks could achieve economic quality without government help if only they were as patient, and worked as hard, as other successful minorities have.

It is true, as Sowell says in his rejoinder, that Ethnic America also cites a lot of past “retrogressions in intergroup relations” and strongly hints that the backlash against “affirmative action” could fuel another such retrogression in the future. But the retrogressions of which Ethnic America speaks involve increases in prejudice and discrimination. Ethnic America does not suggest that these retrogressions had adverse effects on minorities’ economic situations, except in extreme cases such as the enslavement of blacks in the seventeenth century or mass deportation of Mexican Americans in the 1920s. Sowell’s main point is that minorities have made extraordinary economic progress in the face of far more intense prejudice and discrimination than blacks are likely to face in the foreseeable future. Using Sowell’s logic, therefore, the possibility of future “retrogressions” has no obvious bearing on the prospects for black economic progress.

Sowell’s other charges make sprightly reading, but I don’t think they withstand close scrutiny. Despite his complaints about “straw men,” I think anyone who reads his book will agree that, except on the question of “patience,” I have not distorted his meaning in any significant way.

My review said, for example, that Sowell thought “discrimination tends to disappear once markets become competitive.” According to Sowell, what he said was that “the market puts a price on discrimination, reducing but not necessarily eliminating it.” But that isn’t all Sowell says. Markets and Minorities (p. 28) also says that “the more competitive the market, the more the costs [of discrimination] approach a prohibitive level” (my emphasis). If that doesn’t mean that discrimination tends to disappear once markets become competitive, what in the world does it mean?

At the end of my first article I also said that “my hesitant conclusion is also at odds with Sowell’s conservative views, which imply that wage differences are caused by differences in job performance, and that current discrimination in the labor market has no effect on black earnings.” In his rejoinder, Sowell claims he never implied that discrimination did not affect black earnings. Ethnic America just said this was “a complex question, not a simple axiom.” Unfortunately, Markets and Minorities is not as bland as Ethnic America on this point. On pages 22 to 24 it argues—quite correctly—that the more accurately you measure educational skills and credentials, the less difference you find between the earnings of comparable blacks and whites. If sufficiently accurate measurement of skills and credentials eliminated the black-white difference completely, one would obviously have to conclude that labor market discrimination did not affect blacks’ earnings. Markets and Minorities presents two tables, both of which appear to show that this is the case. One shows that black Ph.D.s earn as much as white Ph.D.s. The other compares blacks, Hispanics, and whites who are alike not just in terms of years of school completed but in terms of academic achievement. After discussing the table Sowell concludes:

Holding educational achievement constant, the data do not show current employer discrimination in pay among black or Hispanic male full-time workers born within the United States (excluding Puerto Rico), who constitute the sample for the data in Table 2.1.

Sowell’s only caveat is that Table 2.1 deals with the wages of the employed. Both blacks and Hispanics have above-average unemployment rates, and Sowell hints that this could be due to discrimination. This caveat is of little significance, though, since differences in involuntary unemployment play a very small part in the overall difference between black and white earnings.

For reasons I outlined in my review, Sowell’s Table 2.1 does not in fact have any bearing on the question of discrimination. Instead of admitting this, Sowell now makes the ingenious argument that he never meant to suggest that Table 2.1 proved the absence of wage discrimination. All he meant to say was that Table 2.1 failed to prove the presence of discrimination. I don’t think anyone who read the passage I quoted in context would accept this claim.

Sowell’s discussion of age differences is also misleading. Both Ethnic America and Markets and Minorities make a big fuss about the fact that members of poor ethnic groups tend to be younger than members of rich ethnic groups. Markets and Minorities includes a table showing that the median age of blacks, Indians, and Hispanics is around twenty, while the median age of “European” ethnic groups in America is around forty. Sowell then notes that family heads between the ages of forty-five and fifty-four have family incomes almost double those of family heads under twenty-five. Since European family incomes are less than double those of blacks, Indians, and Hispanics, I said Sowell’s data left the reader “with the impression that if the median black, Indian, or Hispanic were as old as the median European, he would be almost as affluent.” Sowell calls this a “straw man,” and quotes Markets and Minorities as saying that “differences in median age are only part of the statistical picture.” True enough. But the question is how large their part is. The data in Markets and Minorities suggests that age plays a leading role in ethnic inequality. In fact, its role is trivial.

Sowell’s original age data were misleading because, as I noted in my review, a group’s income depends largely on the age of its family heads, not on the median age of the entire group, and the median age of family heads does not vary much from one ethnic group to another. In 1970, for example, the median white family head was forty-six. The median black family head was only four years younger, a difference too small to affect family income appreciably.

Sowell implicitly concedes his original error by substituting data on the age of family heads for data on individuals in his rejoinder and trying to show that the median age of heads of families varies more than I said it did. As I noted in my review, Sowell’s Jewish sample is unrepresentative of the American Jewish population, so its age distribution cannot be legitimately compared to that in Sowell’s census samples. In his census samples, the oldest heads of families are Japanese, with a median age of forty-six. The youngest heads of families are Puerto Ricans, with a median age of thirty-six. This looks like a fairly big difference, but it does little to explain the income difference between Puerto Rican and Japanese families. In 1969, the median income of all Puerto Rican families was 48 percent of the Japanese median. When we compare Puerto Rican families headed by forty-six-year-olds to Japanese families with heads of the same age, the Puerto Rican median is still only 51 percent of the Japanese median. This was the most extreme case Sowell could find. Age presumably explains even less for other groups.

The most disturbing thing about all this is neither that Sowell used the wrong age data in Markets and Minorities nor that he refuses to admit his mistake. All scholars make occasional mistakes, and many are reluctant to admit them. What I find truly disturbing is that Sowell never bothers to make calculations like those in the previous paragraph. The data I used for these calculations come from the very tables Sowell used to calculate the median ages of Puerto Rican and Japanese family heads. If he had really cared whether age played a significant part in explaining ethnic inequality, he would surely have made such calculations himself. While I am reluctant to question anyone’s good faith, I find it hard to escape the conclusion that Sowell is more interested in making debater’s points than in sorting out the causes of economic inequality.

Sowell’s discussion of cultural differences is equally tendentious. Contrary to what you might think from his rejoinder, I never argued that cultural traditions were unimportant. On the contrary, I argued that ghetto culture probably played an important, if puzzling, role in the economic problems of young, poorly educated black males. But I also argued against simplistic cultural determinism of the “Germans are always rich, Hispanics are always poor” variety, noting that cultural values which were adaptive in one context were often less adaptive when a group moved to a new setting, and that cultural values often changed. In support of this argument I pointed out that Irish Catholics enjoyed incomes 25 percent higher than Irish Protestants in America, whereas the opposite was true in Ulster, and that while German and Scandinavians were richer than Italians and Czechs in Europe, the opposite was true in America.

Sowell’s response is to cite other cultural patterns and economic disparities that have persisted over time and across continents. This completely misses my point. Nobody in his senses denies that cultural traditions often persist over long periods and in diverse contexts, or that they often affect economic success. My point was merely that ethnic traditions often change, too. The fact that the differences among European ethnic groups in America are quite small is completely consistent with this argument. Since the differences are large in Europe, the fact that they are small in America requires explanation. Specifically, it requires a theory about why cultures sometimes evolve in ways that help their members take advantage of new economic opportunities but sometimes fail to do so. Neither Sowell nor I has proposed such a theory.

Turning to Sowell’s views on public policy, let me first concede that neither Markets and Minorities nor Ethnic America explicitly discusses Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Both books discuss “affirmative action,” claiming that it has been of little economic value to blacks and has aroused a lot of white resentment. Ethnic America also makes it clear that for Sowell “affirmative action” means “racial quota hiring.” For reasons discussed at length in my review, the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission and federal judges have frequently imposed racial quotas on firms with a history of violating Title VII. As a result, Title VII constitutes one of the main legal bases for “affirmative action” in Sowell’s sense of the term. The fact that Sowell did not make this connection in his books was hardly a reason for my not making it in my review.

Sowell’s rejoinder appears to deny the connection between Title VII and hiring quotas. I can’t believe he is unaware that the courts often impose quotas in their attempt to enforce Title VII. I assume, therefore, that he merely thinks the courts have erred. That is his privilege. But discussing a law as if it means what you want it to mean rather than what the courts say it means inevitably leads to a lot of confusion.

Sowell also claims that my statistics on black progress are misleading because I failed to distinguish progress between 1964 and 1971 from progress made since 1971. This is a puzzling argument, since the studies that Sowell cites as showing that affirmative action has had little effect covered the years from 1966 to 1973. If Sowell believes affirmative action only began in 1971, the studies he cited tell us very little about whether it benefited blacks or not. The tables in my review, in contrast, all distinguished progress during the 1960s from progress during the 1970s. They showed, as Sowell suggests, that blacks made less progress during the 1970s than during the 1960s, but there are many possible reasons for this. Blacks always do better in periods of relatively full employment like the 1960s than in periods of slack employment like the 1970s. Moreover, the gains made during the 1960s were in “easy” areas, where resistance was minimal. Achieving comparable gains during the 1970s was bound to require stronger pressure on employers.

Furthermore, while blacks in general gained less during the 1970s than during the 1960s, there were certain notable exceptions. Among young men with college degrees, the ratio of black to white earnings rose faster during the 1970s than during the 1960s. Regularly employed black women also made remarkable gains during the 1970s, ending the decade with earnings 95 percent of white women’s. If Sowell does not think these gains were due to affirmative action in hiring blacks, he should propose an alternative explanation, and support it with evidence that will withstand critical scrutiny.

My “philosophical” differences with Sowell require no further elaboration. While I think he misses my point, I doubt that further discussion would lead many readers to change their minds one way or the other. But even readers who prefer Sowell’s philosophical outlook to my own should be warned that the evidence he produces to support his views is not very reliable. I don’t know whether Sowell believes that scholars, like civil servants, are really just used-car salesmen in drag, but reading his work certainly weakened my own conviction that there was a consistent difference.

Unlike Professor Sowell, my other critics all seem genuinely interested in getting to the bottom of a difficult issue. I don’t think, though, that Professor Glaberman is on the right track. Construction unions are certainly bastions of white privilege. But the Automobile Workers, Steelworkers, and other industrial unions have provided blacks with access to far better blue-collar jobs than they could have gotten without union help. The net contribution of unionism to racial inequality is thus small, and the ratio of black wages to white wages is about as unequal among nonunion workers as in the labor force as a whole.

It is also true, as Glaberman says, that many firms have moved to the suburbs in order to retain their white labor force. As Stanley Masters showed in his book Black-White Income Differentials, the large gap between blacks and whites is no wider in metropolitan areas with extremely segregated housing than in metropolitan areas where blacks are widely dispersed.

Professor Schwarzschild is right that any quota system will lead to some reverse discrimination. But if the goal of quotas were, as I proposed, to eliminate both conventional and reverse discrimination, quotas that led to either kind of discrimination could be altered on the basis of experience. This would not only reduce the frequency of reverse discrimination but make it a matter of administrative error rather than principle. Such administrative errors would still cause endless controversy. But if we agreed in principle that quotas which led to reverse discrimination should be changed, the scope of controversy would be more manageable.

Such a system would also go a long way toward dealing with the problem Professor Thomas raises. If reverse discrimination were eliminated in principle, even if not always in practice, whites would have less reason to suspect blacks of having succeeded on the basis of skin color rather than talent, and blacks would have more reason to take pride in their successes.

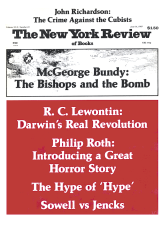

This Issue

June 16, 1983