In response to:

Lust for Life from the October 23, 1980 issue

To the Editors:

It is ironic that Eugene Thaw, an art dealer involved with the Jackson Pollock Estate, appears in your pages [NYR, Oct. 23] as the defender of “Pure” or “New Criticism.” Ostensibly responding to John Richardson’s review of the Modern Museum’s Picasso exhibition, Thaw attacks Richardson’s suggestion that biographical details be gathered as clues to Picasso’s iconography, devotes about half his article to Pollock propaganda, and cites my biography (not criticism) Jackson Pollock: Energy Made Visible (1972) as “the purest example” of impurity.

An artist’s work takes precedence over biographical detail. However, the work can often be elucidated by such detail; the life can only be understood through the work; the two are inseparably connected. Suppression of detail and exaggeration of the “dramatic” create myths about artists. An artist’s life is definitive. No biography can be.

The Thaw/O’Connor Pollock Catalogue Raisonné (1978) and my biography are cases in point. I reviewed the catalogue (Arts Magazine, March 1979) and pointed out various, almost inevitable, omissions and distortions. Nevertheless, this catalogue, particularly in its chronology, adds to the documentation available to me in 1968-1972. Thaw and O’Connor evidently negotiated with the artist’s widow, Lee Krasner (Pollock), regarding which facts and documents to include. This process of making their work “official” also makes it “mythical.”

Initially, in connection with an abortive Time-Life World of… book, Krasner contacted me as “biographer-critic-friend” (Thaw’s characterization), assured cooperation, and directed me to various people in Pollock’s life, including one of his Jungian analysts, Joseph Henderson. Upon learning that some Henderson material was to appear, inaccurately presented, in C.L. Wysuph’s Jackson Pollock: Psychoanalytic Drawings (1970), I and others close to Krasner did what we could to correct the record. Also, Krasner and I met with John I.H. Baur, then director of the Whitney Museum, to arrange for the imprecisely labeled “psychoanalytic drawings” to be exhibited at the Whitney rather than a West Coast gallery.

Throughout the substantial completion of the manuscript, which grew into a biography, Krasner cooperated. Then, because of her difficulty with and distrust of the written word, I read it aloud to her. She asked me to delete a few details, some concerning her contribution to Pollock’s career and work. I thought this had more to do with self-effacement than concern for Pollock’s public image, and I obliged. Krasner praised the book and celebrated its completion with my wife and me.

Two weeks later a letter from Krasner indicated a change of mind and led to a meeting with her and her lawyer. They attempted to refuse permission to quote documents already delivered and, in effect, to suppress the book. My lawyer took the position, which prevailed, that the delivery was the permission.

Of artists’ widows in general and Krasner in particular, Harold Rosenberg wrote presciently (“The Art Establishment,” Esquire, Jan. 1965): “…she is the official source of the artist’s life story, as well as of his private interpretation of that story. The result is that she is courted and her views heeded by dealers, collectors, curators, historians, publishers, to say nothing of lawyers and tax specialists.”

There are connections between Krasner’s and Thaw’s attitude toward biography. During the final months of editorial work, Krasner as executrix of the Pollock Estate made it difficult or impossible for me to complete some private and institutional interviews. After publication she influenced some critics by saying she hadn’t read the book.

But what is Thaw’s article really about? Why is he obsequious to the Modern Museum, Rubin, Schapiro, Rewald, and Barr while condescending to the artists Rauschenberg, Warhol, Duchamp, Dali, Frankenthaler, Noland, and Louis and the writers Tomkins and his own “admired and respected colleague” O’Connor? These questions raise others. Is further manipulation of Pollock’s reputation under way? Perhaps a show by Rubin at the Modern? Must Pollock be equated with Picasso? Must competition be eradicated? And must writers too, who, like myself, recognize Pollock’s contribution but see it focused in a few years of mature work within a tragically short life? To ask this last question, as I have in my book and elsewhere, is not to diminish Pollock, nor to devalue his necessary apprenticeship, but to place his entire body of work in the context of such much longer careers as those of Picasso and Matisse, each of whose total output is qualitatively more consistent, quantitatively larger, and technically more accomplished in more mediums.

Richardson understands that Picasso has nothing to lose from detailed biography. Thaw and Krasner shouldn’t fear that Pollock does either.

B.H. Friedman

New York City

To the Editors:

Eugene Victor Thaw, in his essay in nostalgia for the halcyon days of the New Critics, takes John Richardson and myself to task for presuming the private lives of Picasso and Pollock contributed to their creations. In an issue of your journal which contains references to the psychodynamic implications of Gurdjieff’s youthful cold showers, Chomsky’s archetypal theory of grammar, the Japanese General Staff’s suicidal dependence on custom in the last days of World War II, and W.H. Auden’s anal fissure and recurring wet dream, Picasso’s love life and Pollock’s errant umbilicus seem tame indeed—unless some double standard prevails when discussing the visual arts.

Advertisement

As an historian of contemporary art, I can only commend John Richardson for wanting “every scrap of information” about Picasso (including gossip) preserved. Behind his scholarly greed is awareness that the papers of so many nineteenth century artists and authors were bowdlerized or destroyed outright by misguided propriety. The intimate life of the artist is as important as its public manifestations. The art historian must analyze the cultural, technical and private experience of an artist in order to establish and interpret his or her creative achievement. To interpret a work of art historically—as opposed to defining and evaluating it critically—requires that the object be seen in the total context of its creation, and not from the point of view of current (let alone bygone) critical fashion.

Thaw misrepresents the tenor of my essay on Pollock’s paintings of 1951 to 1953 published by Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art as “Jackson Pollock: The Black Pourings.” He states that I see

…the artist’s use of black paint and his return to his early imagery as an attempt to cure a renewed episode of alcoholism. O’Connor attempts to “read” that imagery psychoanalytically by using as clues some bits of information about Pollock’s infancy and childhood.

Rather, the “clues” I utilize throughout are the configurations of female imagery to be found in Pollock’s early representational work as they can be related to his “abstract” works twenty years later. I never claimed Pollock was trying to “cure” his alcoholism with his art (he sought both psychiatric and biochemical therapy for that during these years) since what is unconscious is unconscious by definition. To claim that my points cannot be verified denies the possibility of intelligent inference based on psychological models already assimilated into other scholarly disciplines.

Thaw’s essay is thus evidence of the disturbing cultural lag which exists between the sophistication of historical and literary studies and the benightedness of those dealing with the visual arts. It also demonstrates the lack of any clear distinction between art historical and critical objectives, due to the old-fashioned view that historians can only operate as critics in the modern field. This need not be the case, as the catalogue raisonné of Pollock’s work Thaw and I edited proves. The implications of those four volumes would now seem to have suddenly dawned on my good friend. I grant contemplating Picasso’s passions and Pollock’s guts may be unsettling, but art—like literature—is more than aesthetic ecstasy, peace of mind, and a good investment.

Francis V. O’Connor

New York City

Eugene Victor Thaw replies:

I am at a loss to understand the purpose of B.H. Friedman’s letter. Annoyed at my passing reference to his Pollock biography as a “soap opera of the modern artist,” he writes another soap opera about agonizing episodes between himself and Lee Krasner that took place long ago. I was not involved in them then and can shed no light on them now. I am sorry that his misunderstanding of what I wrote should have released such emotion and caused a retreat from argument into accusations about art world conspiracies. Several of Friedman’s points, however, deserve a reply:

- I do not see that my career as an art dealer disqualifies me to express views on art criticism—any more than Friedman’s former career as a real estate tycoon disqualifies him.

- As Friedman knows, but apparently needs reminding, I have had no financial dealings with the Pollock Estate at any time and none involving other Pollock works during the years of preparing the Catalogue Raisonné.

-

As our editor at the Yale University Press can confirm, Lee Krasner turned her files over to O’Connor and me at the beginning of the project and never asked for or was granted any editorial control or supervision. She saw the book for the first time only after it was printed.

Nothing I wrote was intended to be “condescending” to the artists Friedman names. In the cases of Warhol, Rauschenberg, Duchamp, and Dali, I simply noted their status as “celebrities” which is, I think, unarguable. It was the misuse by critics of Pollock’s career and reputation as “precursor” for Frankenthaler, Noland, and Louis that I criticized and not those artists or their work. That Friedman prefers both Matisse and Picasso to Pollock is not, in my view, pertinent or even controversial. To be placed third in such company is hardly disparaging.

With Francis O’Connor, whose letter addresses my argument, I must continue to disagree. I wrote at the end of my piece: “To know such facts about great artists can be valuable and interesting, but they are not the essence or the meaning of their works.” For O’Connor, I think, they are. I maintain that neither “Picasso’s passions” nor “Pollock’s guts” are the essential content of their works of art, however much those factors may have been partial causes of their creation. It is the transformation of those causes into something else transcending such particulars which distinguishes art from, for instance, therapy and leads to a result which can, sometimes, offer us the aesthetic experiences O’Connor seems to denigrate.

Advertisement

Analyzing the private emotions of someone who is dead and whom one never knew by “intelligent inferences or psychological models” seems a dangerous procedure to me. Where one cannot know the inner life of a creative person except through the art he has produced, to infer such knowledge, backward as it were, from the work, then forward again to explain the work risks the kind of tautological reasoning and gross error into which Freud himself fell in his study of Leonardo da Vinci, as Meyer Schapiro showed in the essay I cited. I cannot help wondering how O’Connor would deal with, say, Shakespeare, or Vermeer, or a masterpiece of African sculpture.

As I wrote, I am not opposed to investigating the lives and psychology of creative artists when such information can be found, but I would hope for a return to proportion and balance in the critical or historical use of this material which, however interesting, is seldom central to the content of art itself. John Richardson’s work on Picasso is brilliant not simply because of his extensive information about Picasso’s life but because of his acute eye and feeling for his work. But those who have difficulty in approaching a work of art and experiencing it deeply often take refuge in explanatory dodges based on the artist’s presumed state of mind or on private events which may or may not have been accurately reported.

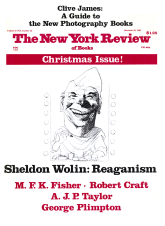

This Issue

December 18, 1980